Remembering Cowichan’s Own ‘Galloping Goose’

This is beginning to look scary.

The April 28th headline of the Cowichan Valley Citizen was a stark reminder that time is running out for the E&N if it’s to be saved as a working railway and not be converted into a recreational trail. According to the Citizen:

Deadline looms to resurrect rail corridor; but Island Corridor Foundation optimistic.

The historic Victoria-Courtenay and the Parksville-Port Alberni railway lines have been down 11 years now because their grades and trestles no longer meet the safety standards enforced by the federal Ministry of Transportation.

We haven’t seen the Dayliner in Duncan for years.

Far more threatening, and what has prompted the court deadline, is that a mid-Island First Nation has legally petitioned to have the rail corridor across its reserve returned to them. Their argument being that the land was appropriated for use as a railway but is no longer serving in this role, so they want the land back.

I could argue here why I believe that, on a practical level, it would be extremely shortsighted to allow the E&N to go under but, instead, I’ll come at this from an historical viewpoint.

I consider myself blessed to have been born when both Island railways, the E&N and the CNR, still actively hauled freight—the latter, almost past my home which was just one house removed from the Saanich shortline (once the Island mainline).

Best of all, the CNR still used steam locomotives!

But I’ve told that story before and I’ll move on, other than to say that, today, I live just one house removed from the CNR Tidewater Line that I walk daily. How sweet is that...

* * * * *

How many Chronicles readers can remember when downtown Duncan was a busy rail yard? When there were four sets of tracks, not one as there is today; when trains ran four times daily and boxcars were being shunted about the yard for hours on end?

Duncan’s E&N station is, perhaps appropriately, a museum now.

This, of course, meant the rail yard acted as a divider and an obstacle course between Canada Avenue and Duncan street. By obstacle course, I mean that it posed a hazard to foot traffic. Although legally forbidden, the shortcut was just too handy and tempting, particularly to those who frequented both the Tzouhalem Hotel and the Quamichan hotels, placed as they were like east and west bookends.

Sad proof of the danger therein is the case of ‘Lord’ William Probyn Thompson who, in April 1947, chose to take the shortcut across the yard in mid-day. Ignoring a moving engine and seemingly oblivious to its ringing bell, he stumbled and fell as he crossed in its path.

The engineer, it was determined at the coroner’s inquest, couldn’t possibly have seen a man lying on the tracks at such a short distance. To the horror of several eyewitnesses, the locomotive passed right over him and dragged him for some distance before the engineer could be waved to a stop.

One of those who’d watched the tragedy unfold did so as he and a companion drove along Duncan Street. The first to reach the prostrate ‘corpse.’ he was amazed to find that Thompson was still alive but “terribly mangled.” Perhaps mercifully, Thompson soon died soon afterwards of his injuries, shock and loss of blood.

Thirty-five years before Thompson’s fatal encounter with a train, R.B. Anderson, a 60-year-old plumber and resident of Duncan for 12 years, was also fatally struck down in the rail yard—not by a train but by a runaway team and wagon that he apparently didn’t hear approaching. Although one wheel passed over him, his injuries were thought to be confined to a scalp wound that required 37 stitches.

There must have been internal injuries, however, as he died a week later.

There were dangers other than switching engines. At least once, what ended with a bang in the Duncan yard began miles away to the northwest on the E&N’s Lake Cowichan Subdivision which linked to the Mainline at Hayward Junction (beside today’s Walmart).

Following the Cowichan River gradient, the two per cent grade to the Summit at Sahtlam meant a climb of 570 feet over a distance of nine miles for westbound trains, the steepest section on the whole E&N line. Two per cent may not sound like much but a runaway car picked up enough speed to coast all the way to Duncan and plow into an oncoming locomotive. Fortunately—amazingly—there were no reported injuries.

Such couldn’t be said for the collision between a northbound passenger train and an automobile one fine June morning in 1913, however.

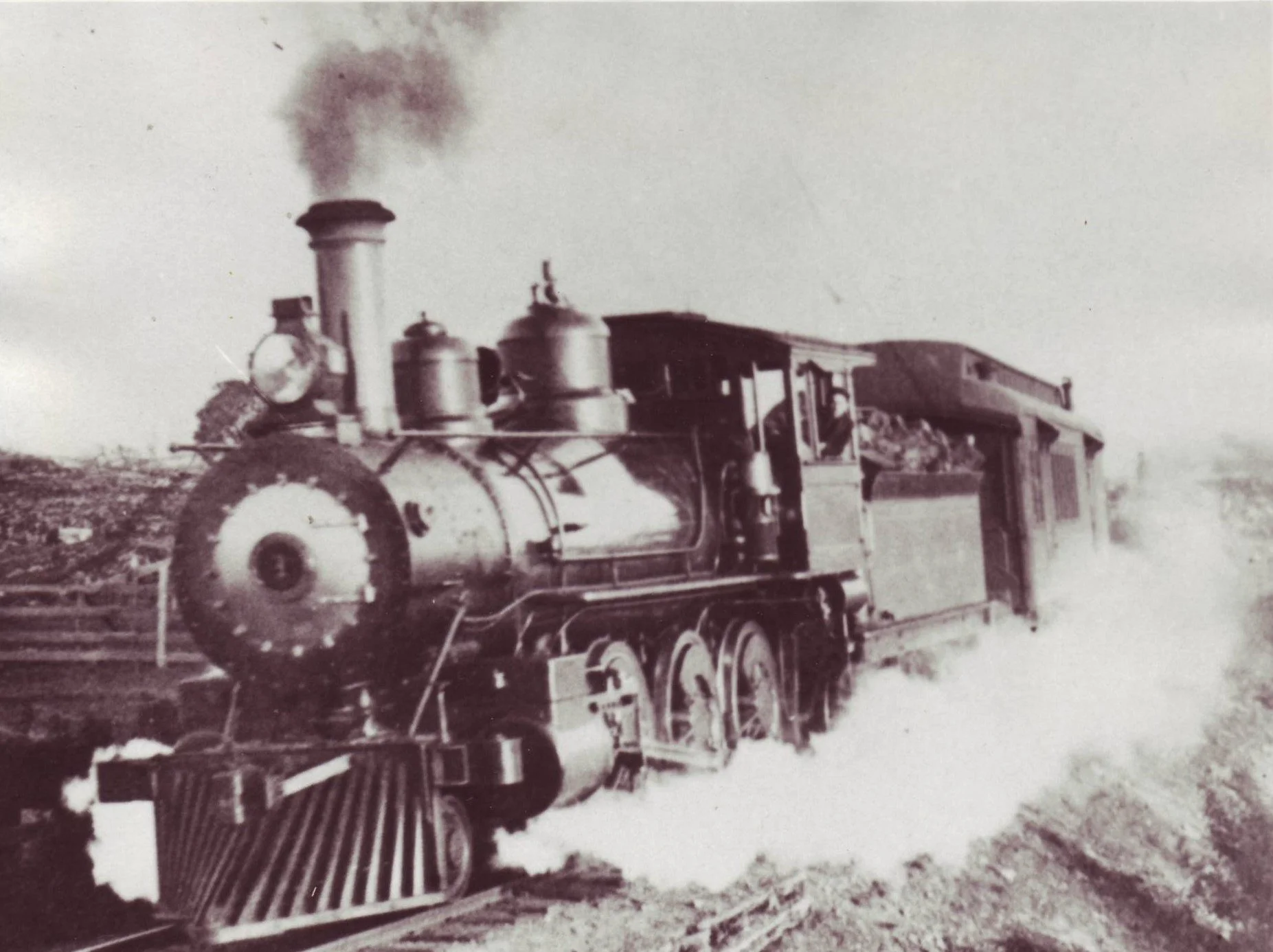

This E&N passenger train appears to be speeding; perhaps making up for lost time after a poker game at the Koksilah Hotel. —Author’s Collection

That’s when Victor V. Murphy, a 32-year-old Irish immigrant was taking driving lessons from Capt. Clifton in the latter’s 30hp Everett roadster. As they headed for Duncan and approached the E&N tracks at the Sherman Road crossing (not the crossing as it is today but somewhat to the north, towards Green Road), Clifton was at the wheel.

He testified to a coroner’s jury from his hospital bed that he neither saw nor heard the northbound No. 1 as he slowed to 10 miles per hour to cross the tracks. The car was almost across when it was struck on the left rear side by the passenger train.

That’s the side where Murphy was seated, the car being right-wheel drive. As engineer Frederick Bland frantically applied the brakes, his locomotive dragged the roadster for seven rail car lengths before he could bring it to a stop. By then Capt. Clifton’s two-seater had been, in the words of a newspaper reporter, “smashed to matchwood.”

So was poor Murphy who’d died on impact.

At the inquest, Bland said he was “quite positive” that he’d blown his whistle as he approached the crossing which was on a blind curve, a crossing that he thought was among the worst on the entire Island line for northbound traffic.

Instead of a police investigation tying up the accident scene for hours while they determined what happened, as would be the case today, the train returned to Duncan with the injured Clifton and Murphy’s body.

A coroner’s jury ruled that Murphy met his death accidentally but thought the railway crossing was “unsafe for general traffic” and recommended that it be moved one-quarter mile to the south (its location today). It found no fault with engineer or motorist. At Murphy’s funeral, which was well attended, fellow members of the Cowichan Cricket Club provided a striking wreath in the form of a bat in the club’s colours.

* * * * *

I’m making it sound as though the local railways were involved in accident after accident which, of course, just wasn’t the case. For many passengers of both the E&N and the CNR, passenger traffic was safe and, usually, reliable. Not always, though, if you remember the Chronicles series on the reminiscences of hotel owner, mining developer, MLA and MP Charles H. Dickie.

His first real job upon coming to the Island was as a fireman on the E&N and he told how the daily passenger train would pause at the Koksilah Hotel, a mile south of the Duncan station, for a pit-stop for the crew. Should the conductor, as often occurred, get into a friendly card game, well, the schedule went by the boards.

If he were on a winning streak, there was no “All aboard!” until he’d cleaned out his opponents. And if he were losing, he wasn’t going anywhere until he either caught up or ran out of money.

The company itself wasn’t a paragon of efficiency, either, if we go by old issues of the Cowichan Leader. Take the experience of M. Leslie Melville. In a letter in the Leader, he criticized the CPR for delays on the Mainline passenger service caused by mechanical failures of the “antiquated old cow catchers” used for locomotives.

The E&N logo.

He was being polite. Raged the editor: “The whole outfit seems to be rotten. The engines are simply piles of junk held together with difficulty, which ought to have been relegated to the scrap heap at the latter end of the last century. The track is vile, the carriages are about as old and dirty as they could be, the lighting(?) of the trains is so bad it is impossible to read on the journey...”

Did he think his carping would do any good? It hadn’t worked in the past: “...In the case of the E.&N., slight digs in the ribs did not serve to show that there was any life whatever in the officials–any more than there was in the engines. The only thing to wake them out of the comatose condition, into which they had fallen, was a jolly good kick. They will probably be sound asleep again in a few days, in which case we shall feel it incumbent upon us to administer another rousing kick.”

A longtime Lake Cowichan resident ‘fondly’ remembered the passenger coaches on the Lake run which were heated in winter by a small wood stove, the seats upholstered in red plush “and there was always a cloud of dust when you sat down on one”.

At the urging of the Duncan Board of Trade mixed freight and passenger service to the Lake was increased to thrice-weekly in the summer of 1922. When necessary, a small portable safe handled valuable shipments–accompanied by a mail clerk armed with a 10-shot automatic pistol.

The Lake-bound mixed train left Duncan about 10:15 in the wake of the Northbound from Victoria. Officially designated the ‘No. 9,’ it was crudely known as the ‘N— Local’ because of its passengers’ mixed racial origins. Upon return, the train entered the Mainline on the northbound ‘Y’ at Hayward Junction (named for Capt. W.H. Hayward, longtime Valley MPP) then backed up the two miles to town.

(Unlike Lake Cowichan, the lack of a ‘Y’ or turntable at Duncan made this routine necessary so that the engine would be heading the right way for the outbound trip.) As this put the locomotive and engineer at the tail end, a brakeman was positioned on the last car or caboose to blow an air whistle at each level crossing!)

If the Southbound, which had the right of way, were running late, the No. 9 often booted it back to town (in reverse, remember), leaving the Hayward telegraph operator to stall the overtaking ‘Superior’ if necessary while No. 9 cleared the track. This years-long practice was discontinued when a reversing train struck a cow!

Mishaps, as already noted, were all but inevitable. At the Lake Wye in October 1912, Alan Wilson, who’d worked his way up from water boy to engineer, felt his engine keeling over as the water-sodden grade collapsed. His fireman bailed out through the open window but Wilson stayed with the locomotive until it came to rest underwater and he was able to swim to shore, coated in oil.

Oops! —Courtesy Kaatza Station Museum

The most embarrassing incident involved three locomotives. After the first one tipped over and a second one did the same while trying to pull it upright, a third engine had to set things right.

* * * * *

The homely forerunner of the E&N Dayliner was the CNR’s boxy, self-propelled ‘Galloping Goose’ for which Saanich’s popular commuter trail is named. —Courtesy Kaatza Station Museum

Best and most fondly remembered of the CNR’s presence in the Cowichan Valley was its 30-passenger gas-powered passenger coach, powered by a Reo engine to a design by the CNR’s vice-president, and operated by Walter Regan who was engineer, conductor and trainman.

No. 15813, a cross between a streetcar and a bus on steel wheels, began service quietly and inauspiciously, on Friday the 13th, October 1922. “There were no speeches or formalities of any kind,” Maj. George Nicholson, a passenger on that historic day, recalled, “no crowds meeting the car at wayside stations, for there were no stations.

“The only stops were either at some interest[ing] scenic point, or where company officials accompanying the party stressed industrial possibilities resulting from opening of the line for traffic. At Mile 60, then the end of steel, the car was turned around at a convenient wye and the return journey made without further incident.”

It soon gained the nickname, the Galloping Goose, which has been perpetuated as the phenomenally popular Galloping Goose Trail, that stretch of the former CNR mainline between Sidney and Victoria that’ has been linked to the Cowichan Valley’s section of the Trans Canada Trail via the Malahat.

Lake Cowichan’s Trevor Green knew the Goose as “The Toonerville,” for a comic strip called “The Toonerville Trolley that meets all the Trains.” He described it as a “formidable box-shaped affair, conspicuously lacking in any form of ‘streamlining,’ and painted dark green. Nor do I recall any vestige of wood in the construction, so that as a result, it was very noisy to ride in.

“‘Sound proofing’ had yet to come, in terms of insulation, so that...a journey to Victoria or north to Youbou was perhaps something of an endurance test to those accustomed to riding in a passenger-coach on the C.P.R., or in a well-upholstered bus or car.

“But the Gas-Car had its advantages, as well, for one could ride to Victoria without ‘changing trains’ in Duncan. For a good part of the way the route was scenic, specially through the Sooke and Colwood districts.

“The vehicle was...equipped with a regular train-engine bell, and a shrill whistle of sorts. Within was a central aisle, with streetcar-type seats on either side, upholstered in some sort of synthetic leather... A water container [was] attached to one wall, with small paper cups or envelopes from which one might slurp a mouthful of stale and tepid water should the need arise.

“A glass case, located near to the roof, contained a small half-axe and a small saw, to be used in case of ‘emergency,’ which implied trouble resulting from a tree across the tracks, or perhaps slight erosion of the line in very wet weather.”

Originally, the Gas Car went only as far as Lake Cowichan where it was “reversed” for the return trip on a turntable at the intersection of King George Street and West Cowichan Avenue. When the line was extended to Youbou, a flag stop was established for passengers at the popular Lakeside Hotel.

Passenger facilities at Lake Cowichan were equally modest, Mr. Green recounting in 1956: “There was a small station, reached from a steep flight of steps, that led up to the railway from the road level, to the right of the ‘overpass’... This station was little more than a glorified shed, but at least it provided a shelter of sorts for passengers travelling south to Victoria or latterly, up the north shore to Youbou.

“And adjacent, and connected, was a small warehouse for baggage and for freight. For some years the mail was brought up to the Lake on the Gas Car, and during the winter months it was a heavy burden to carry the cumbersome mailbags down the narrow stairs, and over to the Post Office.”

He made the journey to Victoria several times during the late 1920s, and found it “most enjoyable for the most part”.

No. 15813 was later replaced by two gas-driven Brills. But the twice-daily service, which had to compete with the E&N and twice-daily bus service from the Lake, never paid for itself and was withdrawn in 1931.

Memories of all this were rekindled during B.C.’s Centenary in August 1958 when a CNR Museum Train consisting of five “old-time” passenger coaches and three locomotives of the “nostalgic day when railroading was young in this transportation-needy country,” made the run as far as Lake Cowichan.

There was something of a replay several years ago when the Island Corridor Foundation staged an excursion train ride between the Nanaimo station and Wellington. Even though the historic Pullman car was pulled by a modern diesel locomotive, it was nostalgic and fun.

As for the future, it appears to be up to Ottawa to make a move or we lose the E&N Railway for all time.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.