Remembrance

Tuesday’s issue of the Cowichan Valley Citizen marked the 25th year that I’ve written the Remembrance Day edition for my Duncan newspaper—a quarter-century-long labour of love.

For this week’s Chronicles, it’s a virtual visit to the CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum. This amazing place, even though situated within CFB Naden, on the CFB Esquimalt naval base, is open to the public, seven days a week, 10:00 to 3: 30 except on statutory holidays, at the cost of a donation.

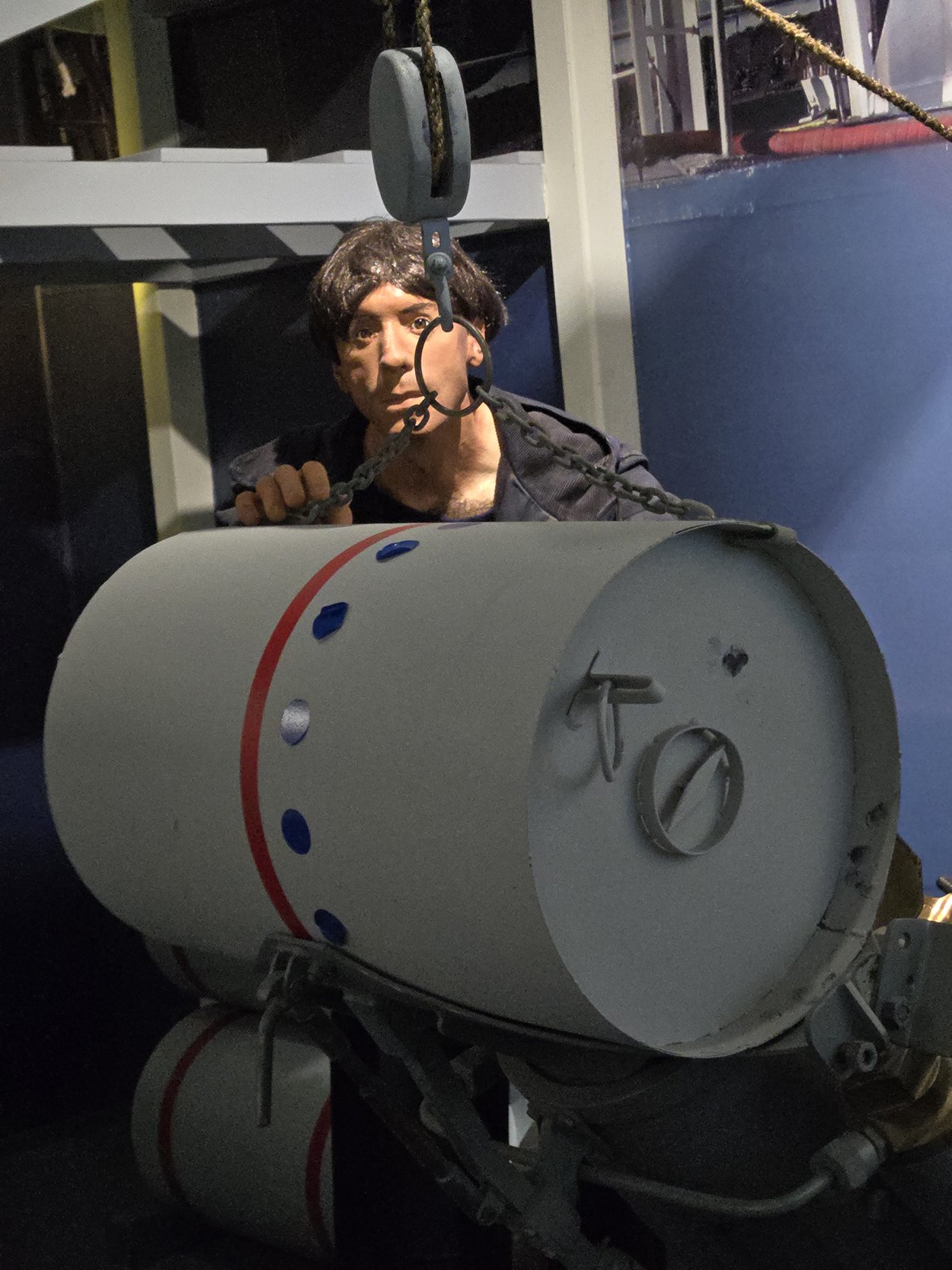

We’ve all seen movies where a destroyer depth charges an unseen U-boat. Here’s what a depth charge looks like, close up—much like an oil drum but with a deadly kick. This is one of the life-like displays that capture what it was really like on, in this case, a small naval ship during the Second World War.

Canada’s naval contribution in World War Two, for anyone who has to be reminded, is that we went from a handful of destroyers to having the world’s third largest navy in just six years!

Very few of those who served were career naval officers and ratings; rather, they were office workers, field hands, college students—former civilians who volunteered to serve King and Country at a time of national crisis. They did so, despite having little or no previous seagoing experience.

Think of it: from office, factory, sawmill, fish boat or wheat field to the deck or the engine room of a heaving corvette or destroyer in the middle of the stormy North Atlantic. In a matter of a few months! And they served Canada well, as the records show, although at great cost—31 ships and 2000 casualties.

The Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum also honours the Canadian Merchant Marine, those civilian heroes who sailed unarmed ships to deliver vital arms, food and fuel to a beleaguered Great Britain.

Make no mistake: remembering the 100s of 1000s of men and women who served during the World Wars, Korea and with United Nations peacekeeping missions isn’t glorifying war, it’s expressing a debt of gratitude.

Lest we forget.

* * * * *

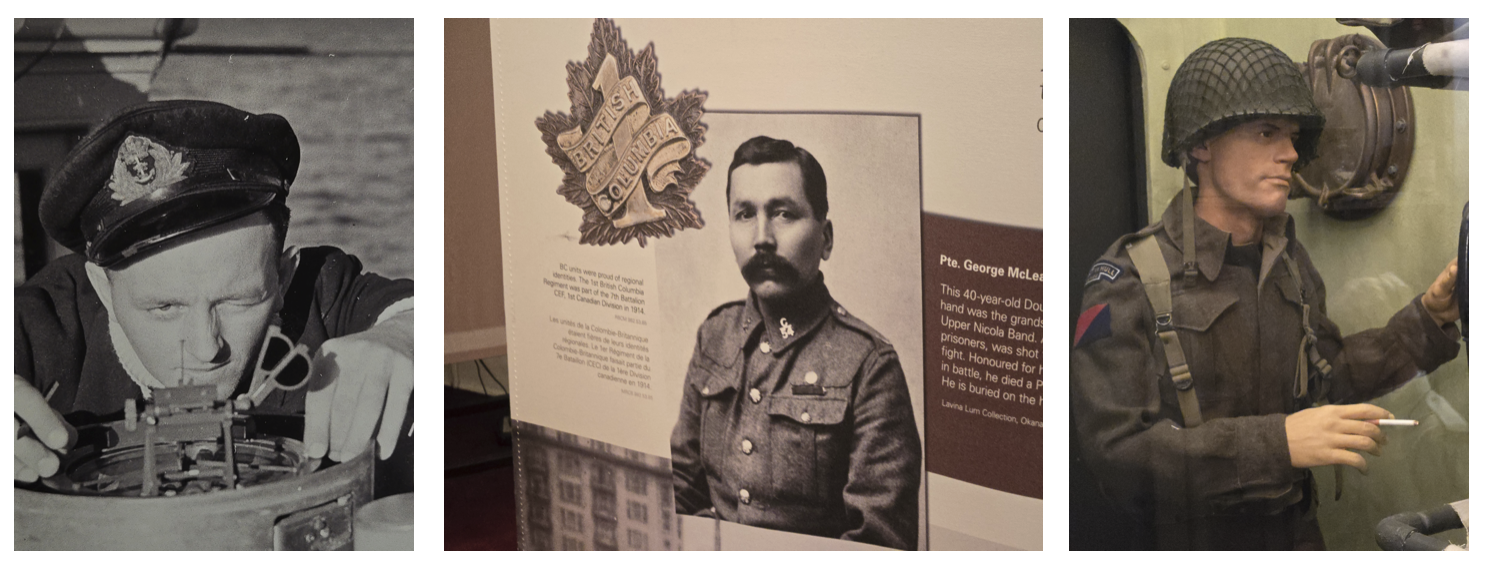

According to its website, the Esquimalt museum’s goal is to collect, preserve, interpret and display the history and heritage of the naval presence on Canada’s West Coast, and of the military on Southern Vancouver Island. The museum exhibits focus on four distinct military groups that have made an impact on Canada’s history and left a lasting heritage:

ïCanada’s Navy on the West Coast

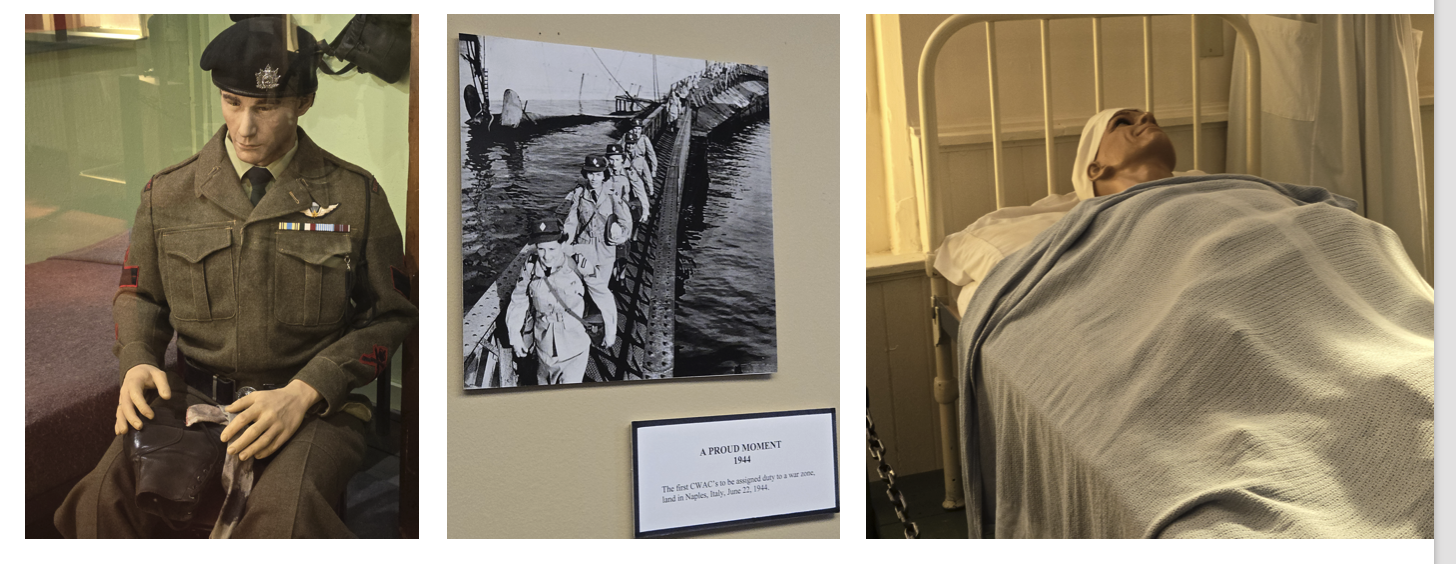

ïCanadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC)

ïWomen’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS)

ïThe West Coast Defences

Back in 1977, the entire museum “collection” was contained in a green, two-door, metal cupboard at the back of the Base Library stacks, and was mainly two-dimensional—papers, books and documents.

Over the past 47 years, thanks to the formation of a Friends of the Museum Society and other initiatives, and the hard work of its many volunteers, the museum has grown vastly in size and scope. In 1994, the museum celebrated its grand re-opening at its present location in Buildings 37 and 39, Naden.

The notion of opening a museum at Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt is thought to have germinated in the 1940s when the idea was first suggested in a Second World War publication. But it’s not clear if any steps were taken then to make the idea reality.

In 1952, the idea began to take tangible form during a visit to Esquimalt by His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh (Prince Philip).

Upon his return to the UK, the Prince arranged that a marble bust of Lord Nelson be sent to the fledgling museum. From such a simple beginning, the RCN museum at Signal Hill, Esquimalt, opened to the public in 1955. After several name changes, what had become the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, eventually moved downtown to Bastion Square, Victoria, in 1965.

The original RCN Museum on Signal Hill. —CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum

The first building to house the museum was something of a museum piece in itself, having been built to house the Royal Engineers when they were stationed at Victoria in the 19th century. The bricks for the structure were brought around the Horn in a sailing vessel.

In the late 1970s, the idea of operating a purely naval museum at CFB Esquimalt was revived. With the help of the Base Historical Committee, a society was formed to collect, preserve and display the history of the naval base of Esquimalt.

The heritage buildings that now house CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum as they looked in days gone by. —Esquimalt Naval Museum

The result of their collective volunteer efforts is today’s CFB Esquimalt Museum and Archives Society.

The museum formally opened in Buildings 20(N) and 29(N) at Naden, on May 5, 1985, the 75th Anniversary of the RCN Navy. “But the museum was still very much in need of a collection in order to create meaningful exhibits. The work of assembling a meaningful collection continued, and the museum, then located in Building 20 at Naden, was opened to the public in 1987.”

In 1994, further expansion and improvements, including the addition of displays devoted to the defence of Canada’s West Coast, led to the grand re-opening of the museum in its present location, Buildings 37 and 39 at Naden.

Parade square and Naden buildings as they appeared in the 1930s, when the area was in use as barracks and training facilities, and as they appear today. —Esquimalt Naval Museum

The brick and frame heritage buildings that are home to CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum were constructed between 1887 and 1892. Designed to be used as a hospital complex, they consisted of pavilion-style buildings with covered verandas. These buildings centred around a grassed area that later became a gravelled parade square and, later still, today’s paved parking lot.

This area, known as Museum Square, is part of a network of outstanding historic buildings at Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Esquimalt.

The Base is composed of several named sections that are geographically removed from one another. Though now integrated, these named segments were originally intended for use by the army or navy of the period in which they were constructed.

Both services had differing conceptions of “proper” buildings. This is evident in the design, detailing, and building materials chosen for the various buildings. Some parts of the base date back to the colonial period, when they were used by the Royal Navy, Royal Engineers, Royal Garrison Artillery and other Imperial Forces.

The Bickford Tower, erected in 1901 as a signalling tower, is the sole example of a building of its type in Canada and is considered to be “an outstanding example of maritime architecture and engineering”.

Building 20, Naden, ca 1891, which now serves as the administrative office and archives of the naval museum, was designed by noted architect John Teague as part of a hospital complex. From 1923-1940, Building 20 was home to various senior naval officers and “continues to attract admiration and interest for its elegant style and scenic location”.

* * * * *

What follows is just a hint of the many fascinating artifacts on display in the Esquimalt Naval Museum, including several of personal interest to yours truly. (An editorial perk.) After all, my father, William Paterson, served 20 years in the RCN, from boy seaman to CPO1 (Chief Petty Officer First Class), which included service in the Battle of the North Atlantic during the Second World War.

Several of the ships he served on caught my attention in the museum, beginning with the bell from the destroyer HMS Foxhound. As a kid, we lived next door to my aunt and uncle. On their fire screen was a solid brass ship’s badge that fascinated me; I ogled it every time I saw it.

When, aged nine, I began collecting naval memorabilia, I was given that crest with its image of the head of a fox hound. Originally, the fire screen had belonged to my grandparents, the crest was a gift from my father who’d liberated it from a lifeboat aboard HMS Qu’Appelle, the former HMS Foxhound.

HMS Foxhound, launched in the 1930s, was transferred to the RCN and became HMCS Qu’Appelle. Her bell is in the Esquimalt museum.—Wikipedia

As HMS Foxhound, this 1930s F-class destroyer served in an arms blockade during the Spanish Civil War, in the Second Battle of Narvik during the Norwegian campaign of the Second World War, at Gibraltar and Malta in convoy duty, sank one U-boat and assisted in sinking another. Then followed convoy duties off South and West Africa before conversion to an escort destroyer and transfer to the RCN.

As HMCS Qu’Appelle, she was assigned escort duties in the Western Approaches and the English Channel. During the Normandy landings, she engaged German surface ships several times before being sent to Iceland for more convoy work. After a major refit in Canada that wasn’t completed until war’s end, she ferried Canadian troops back to Canada before serving as a training ship.

In mid-1946, this weary warrior was placed in reserve and sold for scrap, late in 1947.

Hardly had I checked out the Foxhound bell than I saw a crest from another venerable WW2 Canadian destroyer, HMCS Skeena. This is another of my father’s ships, the one that took him from B.C. waters while Canada stalled on declaring war on Germany until its Pacific Squadron could navigate the neutral Panama Canal.

A crest from HMCS Skeena.

Skeena has been described as “experienced and professional a destroyer as any one of them on the North Atlantic run.”

Unlike Foxhound, Skeena was built in Canada and also had an illustrious wartime career, serving as a convoy escort in the unforgiving North Atlantic. She destroyed a U-boat, guarded the D-Day invasion from enemy submarines and sank surface raids off the French coast, only to be lost upon Iceland’s rockbound shores during a gale. A sad end for a gallant lady.

Here’s a diorama my father could relate to: off-duty, below decks. There was no room to spare on a wartime destroyer. No beds as on modern destroyers, either!

These medals caught my eye as I’ve written about Lt.-Cdr. John Hamilton Stubbs, DSC, before. He attended private school in Shawnigan Lake which gives him ‘local provenance’ here in the Cowichan Valley, although he grew up in the former mining town of Slocan.

The second medal from the left is the DSO, second only to the Victoria Cross. These aren’t the Stubbs medals but in the same display case. Trying to take photos without the reflections of other showcases proved to be challenging on a sunny morning.

Quickly recognized by his superiors as “a superb ship-handler and tactician,” Stubbs was given command of HMCS Assiniboine at the age of 28. During a surface shoot-out with a damaged U-boat, he stood, unblinking, on a bridge that “was deluged with machine gun bullets,” never taking his eye from the enemy and giving orders “as though he were talking to a friend at a garden party”.

The Assiniboine, afire amidships, had to ram the U-210 then finish her off with depth charges.

By the time his Distinguished Service Order (DSO) came through channels, Stubbs was dead, among those lost in the sinking of his newest command, HMCS Athabaskan, off the French coast. Although badly burned, it’s said that he gave up his lifebelt to a young seamen and sang to keep up the survivors’ morale as they awaited rescue and imprisonment by the Germans.

So, yes, I have a soft spot for Lt.-Cdr. John Hamilton Stubbs, too. He’s remembered in Victoria by Ecole John Stubbs Memorial School.

Here’s another display that recalls what my father told me about the time he served on his first ship, the Battle-class trawler, HMCS Armentieres. Coaling was a filthy job as this diorama merely suggests. Not to mention hard work!

A deep-sea diver’s helmet.

As for the diver’s helmet, there’s the story of the Armentieres being salvaged after she sank in 1925. It seems that the diver was down on the wreck for so long without responding to signals from above that everyone became convinced that he’d hooked up or cut his lifeline. However, he finally signalled to be pulled up and when they unscrewed his helmet, they found that he was drunk!

He’d found an airlock in the officers’ mess and broken into the liquor cabinet.

* * * * *

But, as its name implies, this isn’t just a naval museum and it isn’t just about men. Women’s corps and other services are well represented here, too, through both world wars, civil defence and peacekeeping missions.