Sasquatch

Somewhere in the dense rain forests of the Pacific Northwest, particularly British Columbia, is North America’s version of the Abominable Snowman.

This mysterious creature is known throughout California, Oregon and Washington as Bigfoot or Mr. Bigfoot; in B.C., he’s Sasquatch although some First Nations tribes have christened him individually.

Described as being extremely shy and peace-loving, this mammal is said to be “related to both homo sapiens (man) and the Himalayan yeti (Abominable Snowman)”. Supposedly ranging, when fully grown, from eight to 18 feet in height, and weighing from 500 to 1200 pounds, the hairy vegetarian is one of the most persistent and tantalizing legends of the West Coast.

If this all sounds like something out of a comic book or TV’s ‘Incredible Hulk,’ there have been thousands of reported sightings over the past 135 years, and numerous plaster casts taken of footprints measuring up to 18 inches in length.

But, to date, despite ongoing searching that includes an officially sponsored hunt in 1957, no one has come up with conclusive proof that he exists—a living, breathing Sasquatch, or a corpse.

So, today, The Chronicles, which have already explored UFOs and Sea Serpents, looks at the fascinating mystery of Sasquatch.

* * * * *

In January 1994, Courtenay, B.C. wildlife biologist John Bindernagel publicly announced that he, a scientist of all people, believed in the existence of the Sasquatch aka Bigfoot aka Yeti aka the Abominable Snowman.

He’d finally gone public after having found its footprints in 1988 and heard its “whoo whoo whooping” four years after.

His reticence, particularly as a man of science with a reputation at stake, is understandable. But he wasn’t alone. In fact, he was late by at least 87 years.

“Credit” (an even more dubious distinction then than now) for one of Vancouver island’s most credible sightings goes to timber cruiser Mike King. With his brother Jim he’s now a resident of Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery. It’s a long way from their 1840s Michigan birthplace and up-Island stomping grounds.

The Kings were successful speculators in logging, mining and land. After Jim’s death Mike continued a busy career as a timber cruiser and prospector, his travels taking him into parts of the Island’s interior previously unexplored.

It was “inland from the head of Campbell River,” in 1901, that he had his memorable encounter after his Indian helpers had refused to accompany him into what they said was “monkey-man’s country”. Dismissing their urgings not to continue, he carried on until dusk. He was thinking of making camp when he saw it—a “man-beast” kneeling beside a waterhole.

Like John Bindernagel, Mike King was shy, it taking him three years to relate his adventure to a Victoria Colonist reporter. This was quite out of keeping with his reputation as a storyteller. But to continue:

Uttering a “very human cry of mingled terror and defiance,” the creature jumped up and ran halfway up a hillside where it paused to look back. For all of his years in the bush, King was taken aback, too, and kept it covered with his rifle. There followed a poignant stand-off as man and man-beast stared at each other in mutual curiosity and trepidation.

Getting his “nerves together again,” King attempted to approach it but the creature vanished with the speed of a deer. Dusk was falling so the cruiser made camp. But he didn’t sleep that night, instead sitting beside a blazing fire, rifle in hand, and listening to its “extraordinary cries”.

As he argued with himself as to what he’d actually seen, King made mental note of its appearance: the reddish-brown hair and peculiarly long, swinging arms which it “used freely in climbing and bush running”. Morning only confirmed his snap observation made over the sights of his Winchester, there being a small trail showing “a distinct human foot, but with phenomenally long and spreading toes”.

Even postcard publishers got into the act with this series of caricatures depicting Sasquatch in various acts.

Beside the waterhole where he’d first sighted the creature was further evidence: two neat piles of edible grass roots lay side by side, one washed, the other awaiting cleaning.

What was it? His guides had warned him that this was forbidden country, the domain of the wild man. Upon asking further, he was told that, many years before, an ape had escaped from a Spanish ship. Before vanishing into the bush and an uncertain fate, it (obviously a male) kidnapped a Native girl from her west coast village. The result, King’s informant said, was two offspring, one of which was found dead in a crude hut beyond the headwaters of Campbell River. The other, if King were to believe his own eyes, had survived.

He didn’t tell his interviewer how much credence he put into the Indian legend of “ape takes woman” but recalled finding a “semi-human” shelter in that lonely Campbell River country where no Indian would set foot.

Was old Mike pulling his reporter friend’s leg?

You can drive an 18-wheeler through the holes in this legend beginning with the accepted fact that the aforementioned gorilla-human birthing is biologically impossible. As for a captured ape on a Spanish ship, why not? It ranks up there with the stories of lost Sooke, Port Refrew and Jordan Meadows gold mines, with craftsman-like steps carved into mountain stone by their Chinese or Aztec slaves.

Which brings us back to Mike King. A windbag? In Diamond In the Rough: the Campbell River Story, Helen Mitchell wrote in 1976 that Mike had been well known for his storytelling ability. His backwoods adventures were indeed bigger than life; is it any wonder that, even at the turn of the last century, “civilized audiences” were inclined to wonder? His “describing his adventures in such glowing terms,” she thought, likely undermined his credibility.

But what do others say of Mike King whose life story is the equal of, or better than, most British Columbia fiction? The Colonist, upon publishing his belated admission to having encountered a strange, man-like creature, said of “perhaps the most famous backwoodsman and timber cruiser of British Columbia”:

“A man whose word is absolutely good throughout B.C. He knows the wilderness thoroughly, is not at all imaginative, and is a strict teetotaller.”

“On the subject of the wild man he is ready at any time to make sworn attestation to the exact truth of his report, but he has been reluctant to discuss the matter in view of the ever-ready joke.” (—TW)

Praise from B.A. ‘Pinky” McKelvie, noted journalist and historian, is praise indeed. He lauded Mike King as having been one of “the most outstanding timbers cruisers who ever operated in British Columbia...a fine type of a man with an enviable reputation for reliability.”

So, it would seem, John Bindernagel was in good company in 1994.

And just what did inspire King’s confession to the Colonist? Why, the 1904 report that four “sober-minded” Qualicum settlers had sighted their own version of a Vancouver Island Sasquatch. That December, A.B. Crump, J. Kincaid, T.L. Hutchins and W. Buss were hunting in the Horne Lake area, “an uninhabited and little-explored section of the interior of [the Island],” when they came face to face with the impossible: “an uncouth being whom they describe as a living, breathing and intensely interesting modern Mowgli”.

Named after a Rudyard Kipling creation, this apparition didn’t like the four-to-one odds against armed hunters and vanished almost immediately. But not before each man caught what they claimed to be a very good look at him. They were agreed that he was young, his hair and beard long and matted from neglect, and covering much of his body.

(It’s less than 60 air mails from Horne Lake to Campbell River country, incidentally.)

No sooner had they sighted “Mowgli” than he spotted them and was gone, fleeing through the undergrowth, they said, with the agility of a deer.

For cartoonists, Sasquatch was a godsend!

What possessed these down-to-earth pioneers to risk their reputations by going public? In rebuttal to the inevitable snide remarks and skepticism the Colonist proclaimed: “There is not the slightest deviation or variation in detail in the stories they tell which defies ridicule.”

There was suggestion that others had seen this or a similar creature and search parties scouted the hills overlooking Horne Lake without further contact.

The stories keep coming if one takes the time to examine old newspapers. Only months after the Horne Lake incident, and Mike King’s recitation of his encounter, a Nanaimo ship’s pilot told of an unusual incident involving some Indians and a “bear”. They’d been paddling their canoe between Comox and Union Bay, Capt. Owens reported, “when they saw what they took to be a bear, digging for clams on a beach. One of the men raised his shotgun and fired at the stooped figure, at which it screamed, leapt upright—and revealed itself to be a man, naked and covered with hair.”

As the wounded creature headed for the trees, his terrified assailants headed for home as fast as they could paddle. Their lurid accounts of the incident, Capt. Owens continued, “had all the Indians of that section...greatly excited as a result”.

There was more: “The natives who shot at the wild man are emphatic in their statements that his actions were similar to those of the wild man previously seen near Qualicum, for whom search parties have searched in vain.”

Capt. Owens was reminded of a young man who’d vanished in the Qualicum area 12 years before. The master of the SS Nanaimo had among his passengers, one voyage, a 17-year-old who was on his way to Qualicum to vacation with the family of W. Buss (one of the foursome who spotted Horne Lake’s ‘Mowgli’). Shortly after his arrival the young man wandered into the woods and—officially—hadn’t been seen since.

Sure that he’d become lost or injured, searchers did their best but finally gave him up for dead. Recurring reports of a wild man in the region fuelled speculation that, perhaps, the missing teenager of 12 years before hadn’t died but had “lost his reason and has been living, like an animal, in the woods since then”.

The coincidences grow. Next to make a Mowgli sighting was James Kincaid, one of the Horne Lake Four of the previous December. It was summer, evening, and Kincaid was bicycling home from visiting friends when he came to a stretch of road near the Little Qualicum schoolhouse As he did so, he saw a figure ahead and, in true frontier spirit, Kincaid slowed down with the intention of walking along with him.

Curiously, Kincaid (in his written report to Government Agent Bray) states that he whistled to the stranger, who hadn’t heard him approach, “to get out of the way”. What are we to make of this? That the country lane was very narrow, that the pedestrian was in the middle of the right-of-way, that Kincaid had no brakes, or that his control of his cycle was (dare we say it?) somewhat impaired? (But I digress—and, perhaps, imply human foible where none existed.)

Whatever, at Kincaid’s shrill warning, the stranger dove into the bush and began to run.

In seconds he was gone, leaving an astonished cyclist who, ever so briefly, had come to within 10 feet of him: a man about six feet tall, a very stoutly built fellow—“the same looking thing [sic] I saw up at Horne Lake last fall when I was hunting...”

They say the third time’s lucky: Kincaid asked Agent Bray if, next time he encountered such a creature, could he shoot it? He urged the government agent to advise him by return mail. Bray did so—firmly stating that even such unknown quantities as Mowglis were protected by the law in B.C.

The rush of Qualicum area sightings prompted settlers to recall that a child had vanished in the district in 1895. Had he survived—“succoured by the beasts in Mowgli fashion”? Spurred on by such reports, the long missing lad’s father renewed his search for him.

Indian legends describe strange creatures living in the hinterlands.

There’s the ‘Ahootzoos” of the Island’s west coast mentioned by George Nicholson in his Vancouver Island’s West Coast. The Ahousat band, he wrote, “believe them to be descendants of outlawed members of the Man-ous-aht tribe, which made its home on Flores Island, about 10 miles north of Tofino.

“They are said to have lived in caves at the head of rivers... Hundreds of years ago, they raided the villages, carried off young children, stole fish from traps set in the river and killed lone Indians when out hunting. Fear of meeting the Ahootzoos was so deeply instilled in the minds of the younger generation that to this day one seldom finds a Vancouver Island Indian far from salt water.”

One could argue that tribal outcasts ultimately assumed mythical status as bogey men. Nicholson made it plain that he personally ranked Sasquatch and Ahootzoos, along with Victoria area’s Cadborosaurus and Kelowna’s Ogopogo, as “just myths”.

Curiously, not all sightings have been in the Island wilderness—try the Duncan, Sooke and—once—Victoria!

In 1928, Cowichan Tribes historian Jason Ovid Allard decided to investigate the legends and interviewed a resident of the Clallam, Wash. tribe who allegedly had met a tribe of monsters while visiting in Duncan. He’d been warned, said Henry Napoleon, “not to go too far into the wilderness,” but, “in following a buck I had wounded, I went in farther than I expected. It was almost twilight when I came across an animal that I believed to be a big bear.”

To his astonishment, in calling out to the animal, “the creature looked up and spoke to me in my own tongue. It was a man about seven feet tall, and his body was very hairy.”

Much to Napoleon’s relief the monster was friendly, inviting him to meet the rest of his “tribe.” Willing or not, Napoleon had followed his towering guide along an underground trail to meet the others before returning unharmed to Duncan. The strange tribe hibernated in winter and indulged in kidnapping women and children from coastal villages in the summer.

Historian Allard noted that the Puntledge (K’omoks) Tribe had been virtually wiped out by “strange creatures” from Forbidden Plateau, years before. Another legend tells of a young Comox brave who was ordered to journey up the Puntledge River by the tribal medicine man. Captured by strange creatures, he was thrown over a cliff, miraculously surviving his fall and making his escape.

In 1957 the late Jimmy Fraser, of the Songhees Reserve, recalled his frightening face-to-face encounter with a “Sasquatch” near East Sooke’s Matheson Lake. Eighty-four-years-old when interviewed by Victoria Daily Times reporter Humphrey Davy, he was the grandson of King Freezy, the Songhees chieftain in the days of Fort Victoria.

Besides postcards and cartoons in newspapers and magazines, Sasquatch is featured on this windshield decal.

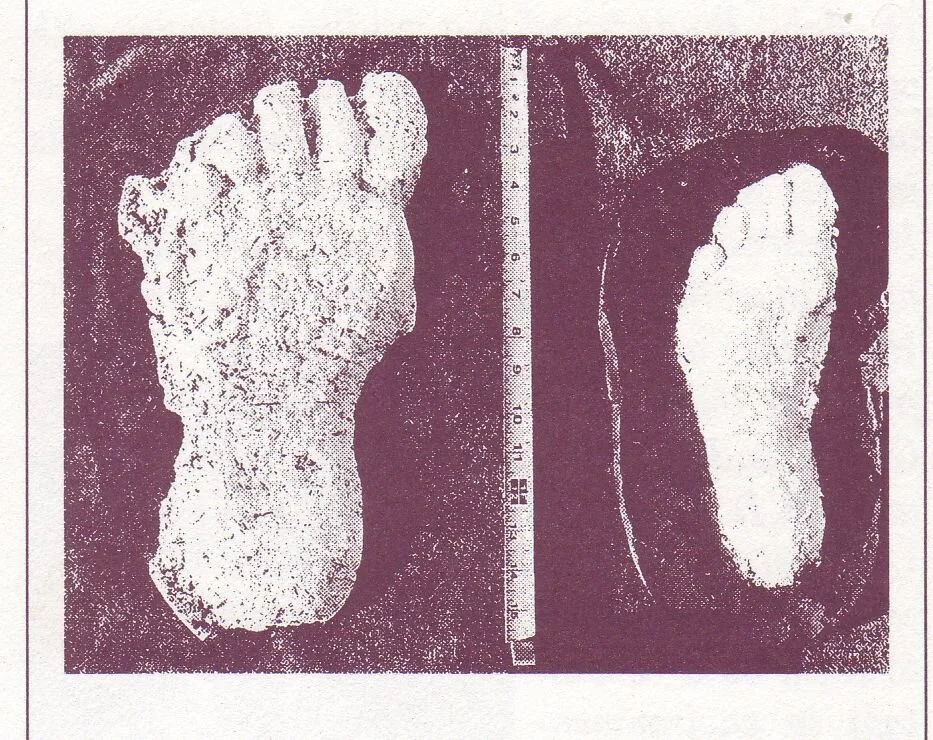

This dramatic photo shows the cast of a 15-inch-long Sasquatch footprint on the left compared to a human footprint on the right. The Sasquatch track was cast by wildlife biologist John A. Bindernagel in Strathcona Provincial Park, B.C., in October 1988. He noted that the giant track was "partially damaged by over-print from a hiker's boot sole".--From a brochure promoting his book, North America's Great Ape: the Sasquatch.

Fraser, acclaimed for his weather forecasting ability, was hunting in the Sooke hills.

Immediately upon shooting a deer, he was startled by an ear-splitting roar. “There, not far away, was a hairy man—maybe 18 feet high—as tall as the mountain trees; he held [my] deer. His eyes glowed like the noonday sun, and the hair on his body was like moss on the rocks. His voice,” the old man recalled with a shudder, “sounded like the roar of a heavy sea.”

Terrified, Fraser began to run as the monster uprooted trees and hurled them at him. He’d escaped—but never set foot in those hills again.

Fraser thought it likely that such creatures could exist without being known to the world at large because they shunned humans and retreated ever deeper into the last of the Island’s original forests.

Obviously with tongue-in-cheek, another tribal member offered substantiation for Fraser’s hair-raising tale in the form of a large bone, shaped like a limb and foot. Unearthed by a bulldozer excavating for a building foundation, the bone indicated its owner to have been at least 15 feet tall. According to the grinning discoverer, who wanted it placed on display in the Empress Hotel: “If anyone suggests that the bone might be that of a whale, we could always tell them that we thought there was something fishy about the skeleton!”

Also inspired by Jimmy Fraser’s adventure, a Port Angeles woman volunteered the theory that Sasquatch had originated in—Saanich. Even that down-to-earth institution, the Victoria Chamber of Commerce, got into the act, having once invited an American female hunter to track Sasquatch with her Shweinburkel, a unique shotgun equipped with a “waffle” valve (she didn’t say why or what it was for), an altimeter, and able to shoot around corners. But—no luck.

Okay, we’ve wandered from the serious and the credible.

So let’s go to one of the most substantiated and documented encounters on record, this one, on the B.C. Mainland, dating back to late June or early July 1884. The Victoria Colonist told not of a wild man’s sighting or encounter, but of his capture!

A CPR train crew had spotted a strange creature scrambling up rocky bluffs overshadowing the right-of-way, about 20 miles north of Yale. Assuming him to be a “demented Indian,” the train crew gave chase and after a hectic five-minute pursuit up the steep cliffs, trapped the fugitive on a ledge. To take him alive, Conductor E.J. Craig climbed 40 feet above the terrified animal and battered it senseless with a rock(!) thus achieving “the desired effect” of rendering poor Jacko (as he was later named) incapable of resistance for a time at least”.

Securely binding their captive with the locomotive’s bell rope the railway men then locked him in the baggage car.

Crowds swarmed into Yale’s little station to view the “monstrosity,” as word of the incident had been telegraphed ahead. Questions as to his species, origin and how he’d been caught flew thick and fast.

Maddeningly, the only query that has ever been successfully answered is the last, as described. Bruises about Jacko’s head (besides those inflicted by Conductor Craig) and body indicated he’d ventured too near the edge of the cliffs, had fallen to the track and lay stunned until startled by the train’s screeching brakes.

All who saw him marvelled at his appearance. Apparently he was a youngster. But a young what?

The Colonist reported him to be “something of the gorilla type, standing about four feet, seven inches in height and weighing 127 pounds. He has long, black strong hair and resembles a human being with one exception: his entire body, excepting his hands (or paws) and feet are covered with glossy hair about one inch long. His forearm is much longer than a man’s forearm and he possesses extraordinary strength...”

And there the story ends! To this day, what became of Jacko and Englishman George Tilbury who planned to exhibit him, isn’t known. The circumstances of Jacko’s capture by a train crew, his being exhibited and seen by the townspeople of Yale, may not totally preclude a hoax but certainly make it unlikely. And to what purpose?

Upon reading the Colonist account, the Rev. J.B. Good of Nanaimo wrote the editor about his experience at the Lytton Indian mission where his congregation had repeatedly him of their encounters with “wild men of the woods”. He admitted to having “laughed at their fears and pooh-poohed the matter, considering the reports to be on a par with their traditional stories about certain lakes and special spots being haunted...”

But, after reading about Jacko, the reverend was no longer complacent.

Since 1884 many others have expressed doubts that Sasquatch is a myth.

Many students of “Sasquatchery” believe the hairy giant is more than a genealogical mishap, but rather, a distinct species. Some of the legends concerning his origin are as fantastic as Sasquatch himself.

One unlikely story is that they were discovered living in what’s now Texas and New Mexico by the Spaniards who named them “Karen Kowarus,” meaning they “walked in streams and caught fish in their hands”. However, after a battle with settlers, the legend continues, all surviving giants were placed in box cars and transported to the middle United States, from where they hiked to the Pacific Northwest! (Surely this is someone’s idea of humour?)

Back to real-life encounters: Although silenced by the derision of his colleagues until the 1950s, it was in 1924 that middle-aged logger Albert Ostman of Fort Langley was “kidnapped” by a Sasquatch family. Although his story would seem the most improbable, it’s considered by some serious researchers to be indestructible.

When John W. Green, publisher of the weekly Agassiz-Harrison Advance, interviewed the old woodsman, he was accompanied by Harrison Magistrate Lieut.-Col. AM. Naismith. A former criminal lawyer, Naismith used every device of cross-examination he knew to reveal a weakness in Ostman’s account—and found none.

Here, briefly, is Ostman’s account:

Camping alone in the isolated forests of Toba Inlet, 100 miles north of Vancouver, he’d had the uneasy feeling that he was being watched. That night he slept with his boots on and kept his rifle beside him in the sleeping bag.

Suddenly he was lifted up—sleeping bag, rifle and pack—thrown over a massive shoulder and jolted about for three hours. When unceremoniously dumped on the ground, the jostled logger found himself in a small box canyon, the guest of four intrigued Sasquatch.

Ostman described them in graphic detail: “The old man [who captured him] must have been nearly eight feet tall, with a big barrel chest and big bump on his back and powerful shoulders. His forearms were longer than common people’s but well-proportioned. His hands were wide, the palms long and broad, like a scoop. His fingernails were flat like chisels. If the old man wore a collar it would be a size 30!”

He estimated what he took to be the son to be between 11 and 18 years of age, “about seven feet tall and might weigh about 300 pounds. His chest would be 50-55 inches, his waist about 36-38 inches. He had wide jaws and a narrow forehead that slanted upward, around at the back, about four or five inches higher than the forehead...”

The remaining Sasquatch were the mother and a daughter—whom Ostman assumed to be his intended bride.

He also mentioned they didn’t eat meat, have fire or cooking utensils, only blankets woven of cedar bark strips.

During the weeks he spent with them, under guard, Ostman ate from his own supplies, a routine that fascinated hosts, who watched in bewilderment. And he still had his rifle but chose not to use it to free himself because he wasn’t sure that shooting a Sasquatch wouldn’t be murder—and because he wasn’t sure his .30.30 would stop the giants, particularly the father.

What really fascinated the males was Olstman’s habit of chewing snuff. After days of watching his pastime, the father grabbed a full box and gulped down its powerful contents. Seconds later, he was rolling on the ground and vomiting.

Snatching up his rifle, Ostman fired a shot in the air and ran, finally staggering, days later, into a logging camp near Sechelt.

This isn’t the only case of Sasquatch kidnapping humans with matrimonial intent. Serephine Long of Port Douglas claimed that, when she was 17, she’d been carried off by a young Sasquatch. Covering her eyes with tree gum, he bundled her off to the mountains and his parents. He treated her well, she said, but she became so homesick that he returned her even though she was now pregnant.

At home, she gave birth to a child that was still-born. Serephine lived to a ripe old age.

One of the best documented sightings is that of Jeannie Chapman in late 1941. A Sasquatch had approached her little house near Ruby Creek, causing the terrified woman to flee with her two young children. When her husband and other railway workers hurried to the scene, they were amazed to see 16-inch footprints, two inches deep in the soft earth. The monster’s stride had been about five feet and he’d crossed a wire fence without slowing. Many journeyed to the Chapman home to see the enormous tracks and to shake their heads in wonder.

But not Mrs. Chapman. She refused to go near the place again and the house was abandoned.

While many more sightings and encounters have been reported and published over the decades, surely 1957 has to be rated the ‘Year of the Sasquatch.’ As final plans were being made throughout the province to celebrate the 1958 Centennial, Sasquatch became a favourite topic of discussion. Seemingly everyone wanted to get into the act.

For an example of his popularity, Victoria’s two daily newspapers alone, in the two-and-a-half-month period of March 6 to May25, 1957, devoted no fewer than 36 articles of varying lengths to Mr. Bigfoot—about a story every other day.

One account was that of the city’s venerable Songhees historian and weatherman Jimmy Fraser, as already explained, but the most interest centred around Harrison Hot Springs whose board of commissioners wanted to organize a Sasquatch hunt. Turned down by the B.C. Centennial Committee, the commissioners financed their own expedition, headed by a young Swiss logger, Rene Dahinden. Dahinden had unsuccessfully tracked Bigfoot the previous year and later became recognized as an authority on the subject who dedicated the rest of his life to capturing a Sasquatch—dead or alive.

Although plans for an attractive French Canadian model to offer herself as bait fell though, the adventurers packed into the wilderness, only to return disappointed.

Besides fighting heavy snow and raging rivers the hunters had had to withstand the fire of respected historian B.A. McKelvie who felt that any hunt for Sasquatch should be led by scientists. An Agassiz clergyman also found fault with the expedition—he was sure that any captured monster would be held in the Harrison Hot Springs Hotel where it would have easy access to alcohol. Sasquatch, he explained, is “unpredictable and dangerous enough”.

Not to be outdone by Harrison, Chilliwack entered the melee by granting Sasquatch voting rights!

The Victoria Chamber of Commerce then joined in the nonsense by inviting the Port Angeles hunter with her shotgun that could shoot around corners. The Centennial Committee, having rejected Harrison’s request to use its grant for a Sasquatch hunt, offered $5000 for the first monster captured. Needless to say, there were no takers.

Yet, despite numerous—and in some cases it would seem indisputable—testimonies that Sasquatch is real, anthropologists and scientists have carefully ignored him. Tens of thousands of dollars and several official expeditions have tracked the Himalayan Yeti but no Canadian or American authority has investigated North America’s own mystery monster.

Provincial anthropologist Wilson Duff, in 1953, said, “I’ve never seen a Sasquatch, and I don’t expect to...” Four years later, he added, “When Dr. Carl [provincial museum director Clifford Carl] takes an expedition to look for Ogopogo [Kelowna’s legendary sea serpent], I’ll go and look for Sasquatch.”

Charles O. Handley, Jr., associate curator, division of mammals of the Smithsonian Institute, in reply to a query, said, “My knowledge of the ‘Bigfoot’ comes only from popular accounts. I am entirely unfamiliar with the Sasquatch.

“Commonly the scientific community disregards stories of creatures such as these until some identifiable portion of the beast can be studied. Unless such a specimen is secured, speculation is fruitless. Usually in the past such creatures have declined to a mythical status when parts purported to have come from them have been studied.”

A University of British Columbia anthropologist has said, a la anthropologist Duff, “Bring me a three-foot femur and I’ll discuss them [Sasquatch].”

But there is record of gigantic bones having been found. A Vancouver couple found a seven-foot skeleton about 1950 and Lillooet coroner Arthur Phair reported the discovery of a “colossal” skeleton. In the late 1920s, at Windermere, B.C., four huge skeletons were unearthed by workmen cutting a trail. Unfortunately, none seems to have reached expert hands for study.

And those tantalizing finds haven’t been limited to British Columbia. Soldiers excavating for a powder magazine in California found the skeleton of a man 12 feet tall. In the 1870s, prospectors found an enormous human-like leg bone and foot near Eureka, Nevada. The leg had belonged to a giant but, despite a thorough search by “experts,” nothing more was found. Many more such discoveries, too numerous to list here, have been made.

In a 1960s issue of British Columbia Digest magazine Bella Coola storekeeper and noted historian Cliff Kopas mentioned an enormous bounty had been placed on Sasquatch’s head. According to the Digest editor, Kopas had spent “hundreds of hours in research to prove his belief” in the existence of Sasquatch and was considered an authority on the subject.

Wrote Kopas: “...My interest in Sasquatchery goes back nearly 30 years when I found a group of Indians—intelligent ones, too—who explained many mysterious noises in the woods by a reference to Sasquatch. Of course, they tried to accompany the reference with a laugh, but, when I convinced them I had, at least, an open mind about it, I had more Sasquatch stories than a pine tree has needles.

“And like mosquitoes, identical details cropped up from illiterate peoples who had no reasonable way of conveying information over hundreds of miles.

“Granted they [were] telling the truth, at least a dozen people, white and Indian, have told me about their Sasquatch sightings...”

The amazing reward, he continued, was posted by a Texas oil king. Kopas said he learned of it from a hunter subsidized by the Texan who wouldn’t reveal the millionaire’s name. No sooner had the Kopas article appeared than a Texas oil man thought to be the one in question was killed in a plane crash.

Kopas, however, was convinced that “just as rich rewards would be reaped from scientific groups if a hunter did produce a Sasquatch”.

Any readers who seriously consider packing into the bush after Bigfoot should bear in mind the experience of an Oregon prospector, 95 years ago. When chased by a band of angry Sasquatch he’d emptied his revolver into one at point blank range—and he didn’t even slow it down. The miner escaped only by barricading himself in his sturdy cabin.

There you are, the highlights of 90 years of newspaper reports, ranging from the incredible and the credible to the ridiculous.

Do Sasquatch—man-beast—monkey-man—Mowgli—Ahootzoos—exist on Vancouver Island or elsewhere in B.C.? Or in all of North America—or world wide—based upon thousands of reported sightings?

It’s easy to dismiss most of these reported sightings as being mere legends, hallucinations or pranks, right?

I leave you with these words of the Rev. Good, when writing to the Colonist about Jacko, the young ape-man captured at Yale. In conclusion he wrote, “It may appear, therefore, that there was more truth about some of these [Sasquatch] tales than was dreamed of in our enlightened philosophy. That Jacko is destined to point a moral or adorn a tale, viz: that truth is stranger than fiction, and facts are stubborn things—especially Jacko!”

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.