‘Seeing the Elephant’ - Harry Guillod Goes to Cariboo

Gold!

It’s one of the most powerful words in the English language, able to—literally—move mountains.

One hundred and 65 years ago, El Dorado was the almost unknown hinterland of British Columbia. No matter that almost no one in the western world had never heard of it or even knew where it was—it only mattered that any man or woman who could scrape together a ship’s passage and a grubstake had a chance to strike it rich!

Among the estimated 30,000 fortune seekers who descended upon B.C. shores in just two years was a young English chemist (pharmacist) named Henry Guillod. He and his companions didn’t make their fortunes, they even lost their shirts in the process. It’s a great story.

* * * * *

It was in the spring of 1862 that 23-year-old London chemist Harry Guillod joined the army of adventurous bound for the Golden Grail of British Columbia's Cariboo.

He was one of the 1000’s who left their homes, families and jobs to seek their fortunes in the wilderness. Few struck it rich, but almost all contributed to the founding of the future Pacific province.

Young Harry Guillod has left posterity a fascinating glimpse of a world long gone. In a letter to his mother, based on notes made in the field, he recorded the hardships he, his younger brother George, and a friend named Philip Johnston experienced in the New World.

Reverend Harry Guillod; later first Indian Agent, West Coast Agency, Department of Indian Affairs, 1881-1903. —BC Archives

“Here I am again in Victoria!” he informed his mother on Sunday, Oct. 19, 1862. "I have seen ‘the elephant’ as Cariboo is called here; bought into a claim on Lightening [sic] Creek, got played out, and arrived here per Steamer yesterday morning in the remnants of my clothes and without a cent in my pocket.

“I had to leave my watch in deposit for my Steamboat fare, and that's why I left Cariboo without a change of clothes; here I am without a shirt to my back; what remains being only a collar and the tattered front; in a dilapidated coat and with one boot between two feet, and all things considered in a pretty respectable plight to present myself at Church...”

Only three short, hectic months had passed since the Guillods and Johnston first landed in Victoria, bound for the Mainland gold fields and filled with high hopes. Yet, by mid-October, he had to inform his mother that he was penniless, in rags, his watch in hock to the steamer which had returned him to Victoria.

Yet, for all of the misadventures which had befallen the threesome since early July, Harry was able to assure his mother that his health had been “firstrate”—in spite of his feet having been constantly wet during their journey to the Cariboo. His spirits however, were “not at all damped” by the hardships and disappointments they’d experienced.

As he penned these lines on the bright morning of October 19th, the chiming of bells reminded him that it was time for church. He hastily concluded his introductory note and, after apologizing to Mrs. Guillod for what he termed a “very dull narrative,” enclosed the diary he’d kept for the past three months.

Esquimalt Harbour looked nothing as it did in this 1910 photo when the Guillod party landed from San Francisco in 1862. —Department of National Defence

The first entry, dated June 28th, recorded their four-day voyage from San Francisco to Esquimalt aboard the steamship Oregon. Although the trip was uneventful he said they were glad to step ashore. Esquimalt Harbour struck him as being “pretty...rather than a fine one, consisting of a collection of a small pieces [sic] of water opening into each other.

“In passing across to Victoria we saw plants which put us in mind of home: blackberries—the same kind of plant as our own but different in leaf and flavour—and several of our wildflowers.”

Their stay in Victoria passed very quickly, as all were kept busy, chopping wood, "going backwards and forwards to town,” cooking, and laying in a supply of provisions for the trip to the goldfields. By the time of their departure, they’d invested the small fortune of $250 in the acquisition of a horse, pack saddle, saddlebags, barley (for the horse), 15 pounds of flour, 10 pounds of sugar, eight pounds of cheese, 10 pounds of biscuits, three pounds of dried apples, four pounds of tea, two pounds of coffee, a ham, a bottle of curry, salt and sundry goods.

Clothing, due to its prohibitive cost as well as the difficulties of transport, was kept to a minimum (undoubtedly a contributing factor to Harry's ragged condition upon his return to Victoria).

Done with Victoria, the prospectors boarded the little paddlewheeler Enterprise for New Westminster. —Wikipedia

At 3:00 in the afternoon of July 8th, after leaving a letter “in our way with all information up to this date," Harry, George and Johnston boarded the steamer Enterprise and sailed for New Westminster. Arriving the next morning, they “found an eligible spot and pitched our tent as we were told that there was no boat up the river till the next morning.

“New Westminster has one one principal street with a hotel or two, a couple of dozen stores, a church and some pretty cottages along the bank of the river, among them a model Swiss cottage. The military station is about a mile from the wharf, and enclosed by forest which is being gradually cleared from around the town. There were Indians squatted on some swampy ground by the side of the river and we heard that the small-pox was bad among them; I saw one little wretch who just getting over it, down by the water where we went to have a bathe [sic].

“As we returned, a steamer came in and on an inquiry we found she left again at 7:00 for Douglas [at the head of Harrison Lake]; so we got some sausage and bread for dinner, packed up in all haste, and went on board the Governor Douglas, a queer-looking steamer, having the paddle wheels, minus boxes, in the stern.”

As they proceeded upriver, Guillod noted the dense woods which crowded the river's edge, and the snow-capped mountains. After spending the night wrapped in their blankets on the floor of their cabin, they experienced the thrill of having their their steamer continually swipe the riverbank.

Once, an overhanging branch became ensnared in the deck cargo, spilling and smashing some boxes of bacon.

Even more hazardous was the driftwood, which slowed the Governor Douglas to a crawl and which had to be pushed out of the way with poles. Upon meeting another steamer, the Douglas accepted further passengers who’d accompanied the Guillods and Johnston from the Old Country. Unlike the Guillod company, however, they were heading for Yale to find work after becoming discouraged by the reports of Cariboo they they’d heard in Port Douglas.

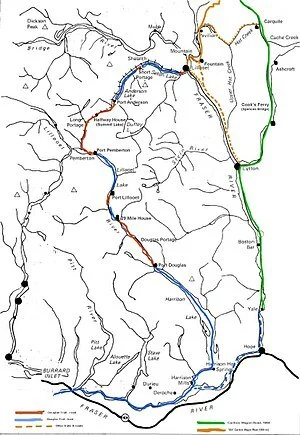

It was a long and arduous trip to the Cariboo.

This little settlement, consisting of a row of log huts and a clearing surrounded by forest, offered little of interest to the travellers. It did bring them bad news, however, as it was here, upon landing, that they discovered that their pack horse had injured his hind leg aboard the ship. This was not their first disappointment with the animal, which had been all they could afford in Victoria, and Harry, had they been able to buy better, would have “wished the creature at the bottom of the sea, or that he would give up altogether”.

But the poor beast, injured hock and all, stuck it out for three miles along the trail, when they made camp.

The following day, ‘Old Moke,’ as Harry had acidly christened their steed, suddenly rolled over in the road, catching his foot in his halter as he did so. Although unhurt, he had to be unpacked. This was the only incident before they reached Lillooet Lake, the greenhorns having taken the precaution of posting a sentry each night.

Once the scene of frenzied activity as gold seekers made their way to the Cariboo, the Lillooet area has returned to pastoral calm in this modern photo. —tripadvisor.com

On July 12th, as George walked their nag and saddle by trail, Harry and Johnston boarded a heavily-laden riverboat for the passage to the mile-long portage between the river and Lillooet Lake. There, they found a roadhouse and enjoyed a “jolly” meal for a dollar each, Harry taking bread and meat along for brother George. He joined them two hours later, “nearly famished,” and they boarded another steamer.

After the first unhappy encounter with mosquitoes, they landed at Pemberton late at night and slept in a roadhouse. Much to Harry's amazement, their faithful pack horse had distinguished himself while on board the steamer. The captain had informed them that their horse, having taken offence to an accompanying oxen, had kicked the poor animal over the side.

The oxen had drowned—and Harry had marvelled at Old Moke’s “showing so much spirit, as he looks awfully quiet”.

Back on the trail, the mosquitoes gave them little peace, Johnston almost going wild, “for we were eaten up... They were perfectly dreadful and I could never have believed anything of the sort could be so bad. We have no domestic pests in England to be compared with these.”

This flying menace so distracted Guillod that he left his prized pocketknife behind.

Much of their discomfort, the mosquito netting they’d bought in Victoria proved to be useless as they lacked broad-rimmed hats with which to keep it off their faces; wherever the netting touch their flesh the mosquitoes bit through.

This is where Harry, his brother and friend Johnston were headed—if the mosquitoes didn’t eat them alive first. —www.pinterest.com

They did manage, however, to avenge themselves against Mother Nature when Harry shot a squirrel and George downed several small birds. They cooked the squirrel, which didn’t prove to be “anything extraordinary”. And so it went, as the adventurers worked their way ever so patiently and, often painfully, to Lillooet and crossed the Fraser.

Besides the mosquitoes, they had to contend with fallen trees, torrential rains, river rapids and trails so steep that their pack saddle continually shifted and required that they repack their outfit time and again. But they overcame all obstacles and crossed Pavilion Mountain.

But, upon coming to the Cariboo wagon road, then under construction, the trail pinched out.

Once, Old Moke almost came to a sorry end in a swamp. By this time their supply of flour was almost exhausted and they’d turned to beans, ham and the occasional bird they were able to shoot. On July 24th, their pack horse, tired of the ordeal, wandered off; despite a determined search, they didn’t find Old Moke.

This was a bad break, but Harry had to confess that “the loss was rather a relief to my mind, for I don't believe the beast would ever have reached Cariboo, and I only wish we had started at first with only our blankets and change of underclothes and tramped it, [as] we should have saved some pounds."

Yet another menace was that of the fly, “several sorts of [which] bite most voraciously; our tent was filled with them and we set to work to kill them, but after covering the floor with fallen warriors, the ranks were undiminished and at last we gave it up in despair.

“You cannot imagine what frights we were from the slaughtered vampires. We used to get close to the fire and be literally smoke-dried to try and get rid of them, but as soon as a puff of wind came and sent the smoke the other way they would pitch into us directly. We could clear the tent and get peace for a few minutes by burning rags; as long as the tent was full of smoke they made themselves scarce, but as soon as it was out, they were thick as ever.

“They stick on one's back in hundreds and as fast as they are killed come on in fresh numbers."

Unable to arrange with any fellow travellers to pack their outfit, they made a handbarrow and set out through a marsh. Their crude barrow broke down within half a mile, when they split up their outfit and proceeded to carry it by stages. They sorely missed the end of their flour as none cared for the taste of beans and found cooking them to be a bother.

“You know what miners’ beans are, I hope," Harry asked his mother. “If not, for your information let it be said that they are like our English horse beans, red and hard and not quite so big and [require] three or four hours boiling to make them eatable."

For the last two weeks of July, Harry disgustedly noted that it was Beans and Bacon! Bacon and Beans!

This, accompanied by a swelling of the face, made life difficult for the young English chemist. By August 2nd, George was suffering with diarrhea and Harry's face was swollen beyond recognition. Head wrapped in a pair of drawers, a red handkerchief and mosquito netting, he must have presented a memorable spectacle to fellow travellers.

Further hardships on the trail necessitated the caching of their pack saddle and saddlebags in a tree and they made another handbarrow. For some miles they were literally covered with mosquitoes which clung to them no matter how strenuously they tried to shake them off.

Nevertheless, despite all the obstacles and agonies, they remained determined to “get to Cariboo” and pushed on.

On August 9th, after making nine miles that day, they enjoyed a visit to a roadhouse where they each had two meals for 50 cents each. After their Spartan fare on the trail, the menu must have seen almost heavenly: beef, mutton, pastry, pudding wine-jelly, fresh butter, milk and coffee.

Here, they had word of Old Moke, but willingly “sold the chance to find him for $10”.

On the 13th, they met a fellow countryman who vainly urged them to turn back. Finally, on August 18th, they reached the gold fields. Two days later, Harry marked his 24th birthday by meeting the famous Cariboo camels. He was less than impressed by their habit of “walking over your tent and eating your shirts."

A week later, Harry and Johnston, taking only a blanket each and a tin cup, continued on to Beaver Pass where they were able to buy two pounds of flour for $2, which they made into dumplings sweetened with sugar. Treated to the best coffee they’d ever tasted, their host took them to be “old miners, which was rather rich, for I fancy I looked very much Cockneyish,” chuckled Harry.

The following day, they were amazed to see their faithful companion, Old Moke, burdened down under the weight of three children.

Harry described Van Winkle Camp as being situated in a valley and “shut in on all sides by high hills, Lightening [sic] Creek running through the centre; you have the sun only a few hours during the day. The town (every place with a dozen huts in it is a ‘town’ here) is one street of wooden stores, Restaurant, Bakery, &c, and a bit of a place with Dr. Kennedy, surgeon on a plate.

“On the side of the hill to the right is the Government Encampment consisting of a few tents. We looked about at the claims, and were told of one, part of which was for sale and which we were recommended to buy. We slept in a log cabin with some miners, one of whom, an old man of the name of Noble, has worked at his claim two season[s] and not ‘prospected’ yet.

“The miners generally are a pretty good sort of fellows, rough but hospitable withal."

The next day was Monday—Black Monday—August 25th, 1862.

This was the day they paid $500 for two half-interests in a claim. Ironically, for all of their hardships—and money—they were to end up even poorer than when they started, Harry learning afterwards that the friendly soul who’d talked them into buying into this claim had been offered $10 to convince them.

Hence, come the Fall, Harry's ragged return to Victoria. Despite this setback, he tried his luck in the Cariboo the following year, before settling in Victoria and, later Alberni, where he distinguished himself with the Anglican church and as an Indian Agent.

* * * * *

Kate Elizabeth (Monro) Guillod and two of their daughters. —Find A Grave

Nanaimo Free Press, July 4, 1906:

Harry Guillod Passes Away at Alberni. Was Formerly Indian Agent for the West Coast.

Harry Guillod, formerly Indian Agent for the West Coast, died a few days ago at his home in Alberni, leaving a wife and three daughters to mourn his loss.

He came to British Columbia via Panama, arriving in Victoria in July, 1862. After a short spell of mining, at which he did not attain much success, he became connected with the Anglican Church as catechist under [Bishop George Hills]. This work he pursued for several years among the Indians on the Songhees reservation [Victoria] and later at Alberni and Comox.

During this period his original avocation of a druggist enabled him to do much good among the natives.

He finally settled at Alberni and shortly afterwards married Miss Monroe... His connection with the Anglican Church was maintained to the time of his death. For several years he acted as Church Warden and also officiated as organizer and choir master.

The remains were interred at Alberni, the funeral being attended by a large number of Indians who much respected Mr. Guillod when he held the position of Indian Agent.