Sirens of Our Colourful Past

Many are the pitfalls awaiting the unwary history student.

Even the experienced researcher can be lured off course by these sirens of our colourful past. To a writer of ‘popular’ history, these detours can be profitable as well as pleasant; ofttimes, research of one story can uncover another. And another and another.

Which is why I liken studying history to digging a hole—the more you dig, the bigger it gets.

Sometimes these yellowing newspaper pages can lead to a dead-end, being too brief or too sketchy to provide more than a skeleton of an article.

So, today, some of these intriguing—sometimes infuriating—diversions of Victoria’s early days from the pages of the old British and Daily Colonist.

* * * * *

The earliest story in my notebook is also my grimmest. Late in 1867, fishermen angling opposite what for decades was the Ogden Point grain elevator, hurried to town with startling news. It was anything but a fish story that they breathlessly reported to the authorities.

The view from Victoria’s Ogden Point breakwater is nothing like it would have been, 155 years ago, when fishermen made their gruesome discovery at low tide. —Victoria Hikes

In the shallow depths of low tide, they’d spotted “the body of a white woman... They say that the hands and feet of the corpse were tied, and that there was a rope about the neck with a stone attached, which anchored the remains to the spot.

“The feet were turned upwards and when seen were 10 feet below the surface. The skin was white and the hair, which they distinctly saw waving with the with the action of the tide, was long and of a brownish hue.”

Police rushed to the scene and dragged the shallow depths from rowboats. But by nightfall, they’d had no success. The next day, they tried again, the Colonist remarking, “That a murder has been committed, we entertain little doubt.”

And—that’s it! Not another word!

Were the fishermen mistaken? Why would they lie? Do these dark waters off the Victoria shoreline, today’s heavily-trafficked Dallas Road, hold the secret of some poor woman’s violent death?

That’s what I mean when I say history can be intriguing and infuriating!

The next mystery is equally tantalizing. This is the strange suicide, in January 1909, of a middle-aged German visitor to Victoria whose carefully concealed identity must yet remain his secret. “Do not blame me for the course I have taken, as life is a total failure as far as I am concerned. It will be useless to find out who I am...”

And find out how he was, so far as I know, they never did.

This forgotten tragedy began with the discovery of a man’s body in Room 44 of the Queen’s Hotel by a Japanese attendant. Police, including a young constable and future VPD Chief named John Blackstock eventually pieced most of the puzzle together.

The deceased had registered as Albert Ehmann of New Westminster three nights before. According to William Baylis, proprietor, the genial German had “appeared [to be] in good spirits”. He paid 50 cents for his room, said the Colonist, and sat around in the smoking room for the whole evening before retiring to bed about 11 o’clock.

All these years later, the Queen’s Hotel is still in business. Do you suppose they still have Albert Ehmann’s Room 44? —www.tripadvisor.com

“On Monday he spent the day about the city, frequently dropping into the hotel, and in the evening, sitting about until nearly midnight when he again went to bed, again paying 50 cents for his room. Tuesday, the same course was followed, and in the evening, after chatting for two or three hours with some of the hotel people until about 11 o’clock, he paid for his room as on previous nights, went into the bar, paid five cents for a glass of beer, and proceeded to his room.

“The money spent for the drink was the last cent the man had in the world. When [his] room was entered yesterday afternoon and the effects of the man searched, not a cent was found.”

Next morning, the by-now popular guest didn’t appear. But there was no indication of tragedy until 3:30 when the attendant prepared to clean the room. Finding the door locked, with no response to his knocking, he asked the desk clerk for the key, intending to clean the room while “Mr. Ehmann” was out.

When the clerk entered Room 44 he made a shocking discovery.

There was Ehmann, asleep in the bed. Embarrassed, the clerk muttered an apology as he edged towards the door. Then something, perhaps Ehmann’s non-response, told him that all wasn’t as it should be. Tiptoeing to the bed, he realized that the German guest would never be roused again.

On the washstand beside the bed was a six-ounce bottle of carbolic acid and a half-drained tumbler of the lethal fluid.

Minutes later, Constable Blackstock arrived to begin a macabre investigation which ultimately was to involve months of exhaustive inquiry across North America and Europe.

At first the case seemed to proceed smoothly enough. Checking the man’s last movements, detectives found “it was plain from his accent that in nationality he was a German, but spoke English fluently, appeared to be a man of education, was polite and courteous, and had a fund of stories which he told to the hotel people as well as to some of the guests.

“On Tuesday night, his last alive, he appeared to be in exceptionally good spirits, though at the time he must have had in his possession the carbolic acid with which he later took his own life, and had come to a determination to end it all.”

A search of his neatly folded clothing produced a notebook. As Blackstock searched the tablet, a page fell out. It had been torn out then replaced loosely beneath the front cover. This was the suicide note. Further in the book were four photographs of an attractive young woman. Inscribed on the back of one were the words, “This is the only woman in the world for me. H.E.”

Some were dated, indicating they’d been taken on the woman’s birthdays at two-year intervals. The latest was placed at Nov. 15, 1908, the woman being judged as 28 years old from earlier notations. All were taken by the same photographer in Germany. Also enclosed in the notebook were the calling cards of three young women.

In an ashtray were the charred remains of several letters and papers, the first evidence of the man having taken pains to hide his identity.

A closer examination of the notebook and personal effects turned up similar clues: he’d carefully eliminated his name from the tablet and the sweatband of his black Stetson.

“The erasing of the names had been done black ink which had evidently been rubbed in with his finger. But while the name on the inside of the hat band is wholly indistinguishable, that on the cover of the notebook is not so thoroughly obliterated and by means of a magnifying glass a name was faintly discerned. It was either ‘H. Gotterlich’ or ‘E. Gotterlicher.’

Aside from the laundry marks on the man’s expensive clothing there were no further immediate clues.

Upon re-questioning the hotel staff, police learned “the unknown...had stated that he had been in San Francisco, leaving there a week before the great earthquake, and he had evidently gone straight to the Kootenay country, for he said that he was in that section of the province when the news of the ‘quake arrived.

“He had been a seaman and, in fact, judging from his conversation, he had been a rover about the world. While he appeared willing and ready to chat he never gave out a hint as to himself, his business or past career.

“Mr. Baylis judged from the man’s conversation that he had been in Victoria before, for he appeared to be acquainted with the city to a certain extent.”

By the end of the day, police were working on a theory. Guessing from his clothing that bore San Francisco labels, and the fact that he’d spoken of escaping the Bay City earthquake, officers deduced that his wardrobe was two years old. This, they thought, indicated he’d been released from the New Westminster jail.

An Oakalla Prison cell. Had ‘Albert Ehmann’ just been released? —City of Vancouver Archives

His clipped hair and “stubby” moustache, they thought, supported this theory. Also, his small bankroll, a check of his hotel, food and drink expenses roughly corresponded with the amount a prisoner received upon release, plus fare aboard the S.S. Princess Victoria from Vancouver.

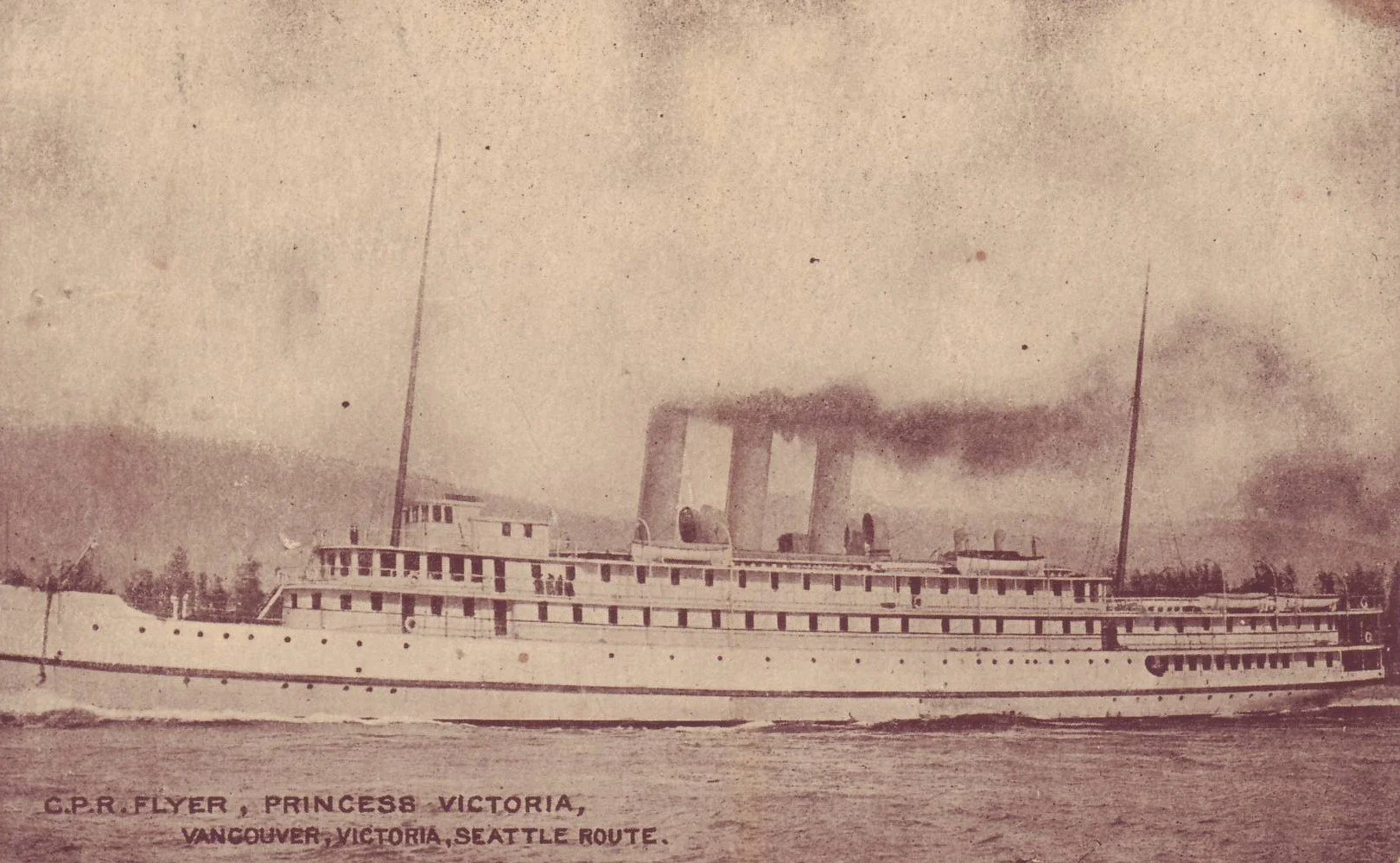

Police conjectured that the pathetic amount of money that Ehmann had spent during his three days in Victoria, plus the fare of the S.S. Princess Victoria from Vancouver, would have added up to the amount usually given a prisoner upon his release from Oakalla. —Author’s Collection

“The initials on the photograph, Mr. Hardwick says, [which] are identical with those of Gottlich are E.J. G. instead of H.G. Gottlich was German by birth and spoke with a slight accent as did the suicide though his English was quite fluent.”

Asked if he knew why his friend had taken his own life, Hardwick sadly shook his head, recalling Gottlich to have been “a happy-go-lucky individual with a genial disposition which made him friends wherever he went and he never appeared to have had any trouble”.

More days of intensive policy inquiry passed with Victorians apparently enthralled by the tragic mystery. Then...the end to Hardwick’s promising identification.

At least, that’s what four friends declared when they viewed the corpse after Hardwick’s visit.

Thanks to the Colonist stories which were picked up by other newspapers, inquiries from as far as Minnesota poured in from persons seeking lost relatives or friends. But none of the descriptions matched that of the deceased. The only remaining clue was the name and address of the German photographer. If he remembered his attractive customer and had her name or address, it would seem a relatively straight path to the identity of the man who’d carried her photos so faithfully.

I continued through later issues of the Colonist until a deadline neared then pressed on. That was 60 years ago and, until this retelling, I’ve never revisited the story of the tragic “Albert Ehmann.”

Perhaps the Provincial Archives holds the key to the identity of the mystery man who ended his life in a Victoria hotel room, half a world away from his homeland and the woman of his heart...

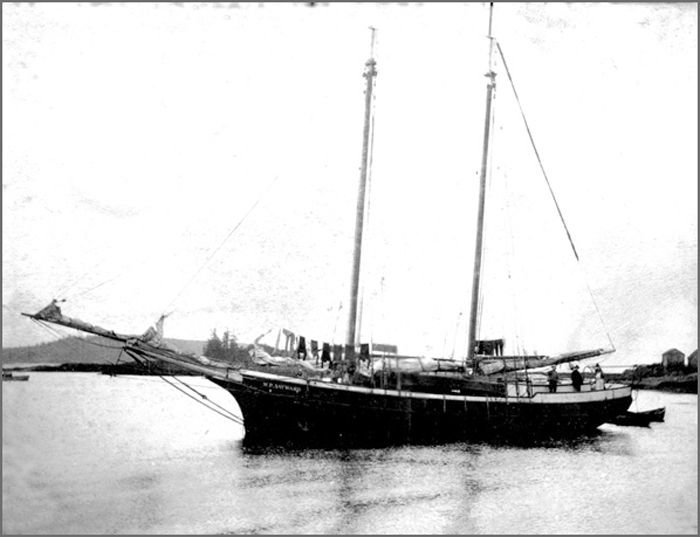

On these same pages is reported the search for one of Victoria’s most familiar characters, Andrew Davids, known by all as ‘Speak Easy Dave’. For 25 years the old Norwegian had been a waterfront fixture. Once, he’d sailed with Gustav Hansen, the famous ‘Flying Dutchman.’

In his prime, ‘Speak Easy Dave’ had been a star of Victoria’s fabled sealing industry. —www.pinterest.com

In his day he’d been accorded the hard-won honour of finest seal hunter afloat, known from San Francisco to the Bering Sea. But a quarter-century of liquor and age had rendered him fit only for the job of watchman aboard the launch Elwood.

When he didn’t report on schedule to owner Frederick Smith, proprietor of the Light House Saloon, a two-week-long dragging of the harbour was begun.

Sadly, again, I had to move on, leaving the search for Speak Easy Dave to an indefinite if predictable conclusion. Some day, with time to spare, I must return to the January 1909 Colonist. (Yes, the Colonist is digital and online now, meaning that I can research it from the comfort of my library office...but...)

Happily, the last of this foray into incomplete mysteries is of a lighter note—a hoax, to be exact.

It all started with an advertisement in a Seattle newspaper. A retired British officer, the wealthy owner of a “palatial” Victoria estate, desired to engage a competent housekeeper to oversee his large staff of servants. He offered the fabulous salary of $35 a week plus numerous fringe benefits.

It was a housekeeper’s dream position. No fewer than 35—“some young and able, some sedate, others fascinating, and the majority of the fair, fat and 40 type”—responded to Victoria P.O. Box 567.

They soon received—all of them—an invitation from Mr. H. Maddock to come to Victoria.

Which created no little confusion when the hopeful ladies, none of whom was aware of her many competitors, descended upon an unsuspecting city.

Citizens trembled before the wrath of some of the more forthright who soon realized that something was amiss. Chief victim of their righteous indignation was real estate agent V.C. Maddock, who was listed in the city directory; first came polite inquiries followed by confusion then outright rage.

Poor Maddock was so besieged that he was forced to call in police for protection. But not before he passed the buck to another innocent Maddock, the manager of a Vancouver sugar refining company. This gentlemen stayed at the Empress Hotel much of the year and, fortunately for him, was out of town when came the female invasion.

Contacted by telegram, the executive graciously offered to pay the expenses of the first two women to reach him, unaware of the 33 others.

When apprised of the real situation, however, he immediately informed the ladies that it must have been his brother who’d placed the ad.

Finally, it was decided that all were the victims of a practical joker, a friend of either of the Maddocks. For some of the ladies it was anything but funny as they’d surrendered positions in Washington when assured of more attractive employment in Victoria.

* * * * *

Just four of the fascinating stories to be found in the pages of old Colonists.