Smuggling Has Always Been With Us

International borders, it seems, are an invitation to smugglers of humans and goods. You know, build it and they will come.

Originally, opium was legal and, for years, Victoria had several manufactories. It was sneaking it across the international border that Canadian and American Customs officers frowned upon. —University of Victoria

Certainly, the international waters between Victoria and Washington State, primarily those of the San Juan and Gulf islands, have been the arenas of illicit activities almost since the arrival of the first Whites.

Today, it’s primarily narcotics and, to a lesser degree, illegal immigrants. Unlike the latter, the contraband flowed both ways; south, during American Prohibition and north, when B.C. “Bud” was a desirable export. In the old days, it was mostly opium from the Orient, and Chinese immigrants using B.C. as a doorstep to the U.S.

All these years later, as the news media frequently reminds us, the battle between smugglers and law enforcement agencies goes on.

* * * * *

Upon his passing 140-odd years ago, Victorians termed James Kelley “a picturesque waterfront character”. Those with longer memories—and sharper tongues—were more forthright. They called Kelley by his true profession: smuggler—and worse.

For more than 20 years, he’d led the United States Customs and Immigration officers a merry chase. In fact, it was common knowledge that, right up until his death aboard a pile-driver at Port Townsend, American authorities had kept a constant watch on the smuggler's little shack on the Victoria waterfront.

Kelly's pretensions, with slight attempts to lead an honest life, were, in the words of a newspaper reporter, "the scantiest semblance toward labour. In spite of the close watch on his movements, with but the single exception, not a successful capture in committing smuggling has been effected”.

This smuggler extraordinaire’s single fall from grace (i.e. the only time they caught him in the act) occurred in 1900, at Kanaka Bay, San Juan Island. A U.S. Revenue cutter, under the command of Lieut. West, overhauled him just as he was about to anchor a small boat crowded with 60 “contraband” Chinese he’d transported from Victoria.

At least, Kelley was a good sport, unlike many others of his calling. With true professionalism, he admitted his guilt and paid the penalty, a one-year sentence in the penitentiary.

The U.S. Revenue cutter Oliver G. Wolcott, shown here in Victoria Harbour, was kept busy chasing smugglers like James Kelley. —BC Archives

Alas, his rehabilitation left something to be desired: “Officials familiar with the character of the man attribute no benefit from the imprisonment,” a reporter noted with an acidic pen. The same officials who’d expressed something less than satisfaction with Kelley's rehabilitation, conceded that his greatest stock in trade was his " stealth” which, they said, “was great”.

Again and again, a generation of American Customs and Immigration officers had schemed to catch Kelley red-handed. They used every conceivable trick and employed all available manpower. Despite these efforts, but for that one time on San Juan Island, Kelley slipped through the net and delivered his cargo, either in the form of illegal immigrants or opium.

He displayed such “neatness and resourcefulness” over the years, in fact, that his antagonists were forced to admit, albeit reluctantly and privately, to having respect for his ingenuity and daring.

Upon the old smuggler’s passing, his former pursuers recalled with something akin to affection, the time that F.D. Heustis, Collector of Customs, had received a tip that the old fox was planning to move a large shipment of Chinese aliens across the Sound. For weeks, officers watched and waited. Finally, bored beyond endurance, they reported to Heustis that Kelley had given no indication of preparing for another shipment. Deciding that the tip had been erroneous, Heustis recalled his men.

From his shack beside the Inner Harbour Kelley plotted his next move—often while under surveillance from US Revenue officers. —BC Archives

No sooner had they returned to Port Townsend than word was received that Kelly had sailed with a human cargo.

Sure that he was headed for his usual “port of entry” in the San Juans, Heustis dispatched a small army of inspectors to head him off. Among those taking up the pursuit was Chief Inspector Thomas Delaney who, with another official, found an iron staple secured to a tree in a secluded cove. This, he was sure, was Kelley’s secret mooring place, and they hid in the bushes.

Late that moonless night, they heard a boat approaching and they leaped out. The midnight marauder was Kelley, all right—red faced and red-handed. Thus his year in durance vile.

On another occasion, American Customs officials received word that he was planning a large shipment of opium from Victoria. Once again, a revenue cutter crowded with inspectors raced to intercept him, this time in Jefferson County. Sure enough, Kelley unwittingly kept his appointment and the cutter surged in pursuit of his little schooner.

Caught in the narrow confines of Scow Bay, the smuggler’s capture seemed imminent, as the cutter rapidly devoured the distance between the two craft.

Much to the officers’ consternation, however, Kelley, rather than wait for them to come alongside, leaped over the rail and swam to shore. When the revenuers stormed the beach on which he’d landed, and made a thorough search of the adjacent woods, they found not a sign of him. As it turned out, however, Kelley's escape wasn’t a total loss: they stumbled upon another long- time offender, “Old Man” Jamieson, who ‘d was hiding there because they’d surprised him him in some illegal enterprise of his own.

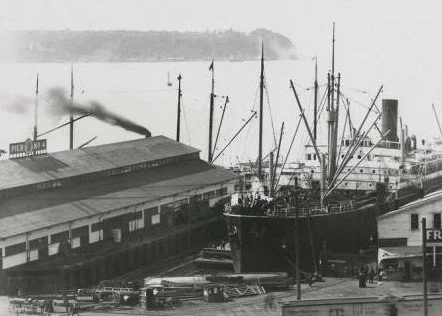

The Inner Harbour was alive with shipping in time of smuggler James Kelley. —BC Archives

But the constant strain of attempting to keep one step ahead of the authorities eventually exacted its toll. Kelley, who’d been rated among “the most successful and persistent violators of the law” in the Pacific Northwest, began to slow down. As the years passed, he apparently chose to forsake the bigger jobs until, by the time of his death, he was all but retired.

American officials however, had never relaxed their vigilance. It was later learned that, several months before Kelley slipped through their nets forever, he’d “displayed an energy” that had alarmed them.

Adding to the Americans’ concern was the fact that Kelley, who had no visible means of support, began to give every indication of prosperity. This could only mean, Customs officers surmised, that he was up to his old tricks, and the watch over his shack beside the Inner Harbour was doubled.

Then... Kelley was gone, this time forever, and Victorians who’d deplored his nefarious career and escapades, mourned the passing of one of the more colourful characters of their waterfront. None could deny that Kelly had been one of the greatest smugglers ever to slip anchor for a midnight run to Puget Sound.

And this was no small praise for a region with a “rich” past in smuggling of all kinds.

General respect for the old smuggler had been tempered, however, by the belief of the authorities that Kelley had, on more than one occasion, when hard-pressed by a Revenue cutter, ditched a cargo of opium or Chinese aliens over the side.

* * * * *

For some illegal immigrants, the possibility of arrest and imprisonment was the least of their worries.

I'm referring to Illegal Asian immigrants who made it to B.C. then had to complete their flight as human contraband into Washington State. Not all of them made it. As we’ve seen, for years, even decades, the notorious “Pig Iron” James Kelley made a good living as a smuggler, operating between Vancouver Island and Washington.

Pig iron? He smuggled iron ingots? Of course not, he smuggled opium and Chinese immigrants—once as many as 60 aliens in a single cargo, said to have been the largest load of its kind. That particular run was the one that cost him a year in Washington’s infamous McNeil Island Penitentiary.

Washington State’s McNeil Island Penitentiary where Kelley served a year, his only jail sentence during a career as a professional smuggler. —doc.wa.gov

Kelly acquired his nickname from the fact that, thereafter, he always carried a secondary cargo of scrap iron for those occasions when he had the misfortune to run into the U.S. Revenue Service while on the job.

If it became apparent that he couldn't outrun a cutter, he simply got rid of the evidence by weighting down his illegal passengers or cargo and dumping them over the side. He got away with this more than once, legend tells us.

It does sound like something out of the imagination of, say, Jack London, but, as late as 1914, it was reported that three Japanese stowaways had narrowly escaped this fate: “Smuggled men have to swim—strong suspicion at Seattle that stowaways brought from Japan are thrown overboard with hands tied,” reported the Victoria Colonist in a front-page story.

“SEATTLE, May 14. - Nonogoueni Kamaskuki, an officer of the Japanese steamer Awa Maru, was arrested in Tacoma today and brought here, where he was placed in the county jail in default of $3,000 bond on an indictment returned by the Federal grand jury, charging him with smuggling three of his countrymen into the United states.. "

Seattle had its problems with smugglers, too. —Seattle Public Library

The Contraband passengers had boarded the ship at Yokohama where they stowed themselves away, allegedly with Kamaskuki’s help, for 120 yen apiece; upon arrival in Seattle, they were expected to swim ashore. Well, not expected to swim exactly. As each man was brought up on deck, Kamaskuki had his hands tied.

Miraculously, all three survived, one man because a deckhand helped him, the others for reasons unstated. Upon the officer being arrested, it was recalled that “several bodies had been found floating in in the vicinity of the dock at various times, and that in several instances the hands had been tied”.

(Shades of Pig Iron Kelley!)

At last report, U.S. District Attorney Clay Allen was promising that if the ongoing investigation conclusively tied Kamaskuki to any of these deaths he'd be charged with murder.

Two months later, and closer to home, it was reported that police were looking into an alleged plot by smugglers based in Seattle, Tacoma, Sacramento, Stockton and San Francisco to bring in as many as 300 Chinese immigrants aboard a chartered ship from Macau.

From an isolated northern B.C. Island, they'd be taken to the Skeena River to blend with cannery workers whence they had make their ways south.

They also had to make make their own arrangements to go on to the U.S. if they so chose. The cost of being smuggled was almost the price of the infamous Head Tax, incidentally: $300 to $500. Police on both sides of the border had their own take on this plot which, they said, wasn't to smuggle Chinese, but to swindle those who put up the money to finance the scheme.

Then there was the time that the American Revenue cutter Grant, Capt. Dorr Francis Tozier commanding, struck the rock that bears his name in Saanich Inlet, near today’s Mill Bay ferry slip.

What was the Grant doing in Saanich Inlet? Why, looking for opium smugglers. (Which goes to show that the close cooperation between Canadian and American law agencies has been with us for a long time.)

In this case, the smuggler was named Jim Jamieson and he only just got away by jettisoning his cargo, valued at $20,000 (much more then than now). Years later, Jamieson would lose more than his cargo, taking a fatal bullet while fleeing from an American Treasury agent.

So here we are, a century and more later, and the war goes on.

In 2003, it was reported that Vancouver had become a destination port for international cocaine smugglers. Less than a year later, it was southbound B.C. marijuana that made the news. As these and other drugs continue to do to this day.

Dare we hope that illegal immigrants having to “swim” for their lives while bound or chained to scrap metal is a thing of the past?