SS Minto: Lady of the Lake

In 55 years she steamed 2.5 million miles and won the affection of all, seaman and passenger, who boarded her. When she died, 1000s, from coast to coast, mourned.

In 1896, the Canadian Pacific Railway had assumed control of the defunct Columbia and Kootenay Railway’s steamboat service, comprising seven steamers, 10 barges, various other assets, and contracts to construct three more vessels for use on the Arrow and Spokane lakes. The Kootenay, Rossland and Nakusp entered service on schedule, the Nakusp being lost to fire at Arrowhead, Dec. 23, 1897.

On a wintry day, S.S. Minto plies her rounds on the Arrow Lakes “milk run”. —Courtesy Canadian Pacific

In the meantime, the CPR had ordered two 830-ton sternwheelers from Toronto for its ‘All Canadian’ Stikine River route to the Klondike gold fields. When that scheme proved unfeasible, and with the sinking of the Nakusp, the 140-foot sisters Minto and Moyie were assigned to Columbia River and Kootenay Lake respectively.

Shipped by rail in more than 1000 pieces each, the ladies were assembled, lengthened 20 feet, and launched at their destinations. In following decades, the lovely twins were to write illustrious chapters in provincial maritime lore, and earn warm niches in the hearts of those who sailed in them.

Minto, named after the Earl of Minto, then Governor General, became the pride of the Arrow Lakes. During the next half-century, she faithfully applied the 134-mile ‘milk run’ between Robson, at the southern end of Lower Arrow Lake, and Arrowhead, at the head of Upper Arrow Lake.

The steamers Trail, Rossland and Minto tied up at Arrowhead in 1900. —Wikipedia

Prior to the completion of the Kettle Valley Railway in 1930,” it has been noted, “the Arrow Lakes, actually a widening of the Columbia River, form the only route of travel to the Kootenays and the state of Washington, from the mainline of the CPR west of Calgary. The sternwheelers on the route, whose scenery is unsurpassed anywhere on this continent, were something like those of the Mississippi—glamorous and well-patronized.”

Originally, the Columbia and Kootenay Steam Navigation Co. had operated six first-class steamers on the narrow Arrow Lakes route between Revelstoke and North Port, Wash. But with the eclipse of Kootenay mining, dwindling freight and passenger traffic meant the end for half of the romantic fleet and the CPR kept only its three newest steamers, the Minto, Rossland and Kootenay.

Rossland and Kootenay had been built 1897 along the elegant lines of inland Oregon and California steamers, as specified by Capt. J.W. Troup. “The Rossland,” wrote Edward L. Affleck, “with its sheer lines and powerful engines, was capable of an astonishing turn of speed (and an astonishing fuel consumption), while the Kootenay was a broader-beam, more matronly vessel...

“The Minto, having originally been designed for service on the Stikine River route to the Klondike, could not match her sister[s] for speed and appearance, but she could boast the more durable assets of a low fuel consumption, a very shallow draft (5’ 1”), and a steel-constructed frame.”

Speedy Rossland retained title of the monarch of the inland fleet for a further 10 years until overshadowed by a newcomer, the shining three-deck, steel-hulled mammoth, S.S. Bonnington. With her mighty compound reciprocating engines, the new 1700-ton sternwheeler reigned supreme.

Ironically, she was too late, belonging to another age. Within nine years, she and Minto were alone, but for the little tug Columbia. Gracious Rossland had foundered in 1916 and sturdy Kootenay had been beached as a houseboat.

Through the 1920s, Bonnington churned the placid waters of the Arrow Lakes, Minto in the humble role of relief steamer. But Minto’s years in her glittering kin’s shadows were about to end. In 1931, her turn finally came when Nelson and Nakusp were linked by road and the Bonnington was laid up.

For seven years, the CPR promised she’d be restored to service. But when season traffic didn’t warrant her return to duty, the company began cannibalizing her equipment for other vessels in the B.C. Lakes and River Service.

Interest in the forlorn beauty was revived in 1938 when it was rumoured that the provincial government would purchase and remodel her as a car ferry. But it wasn’t to be and, in 1944, she was sold for dismantling. Throughout these years, Minto quietly plodded the milk run. “The Arrow Lakes ‘plain Jane’ had outlived her more glamorous sisters.

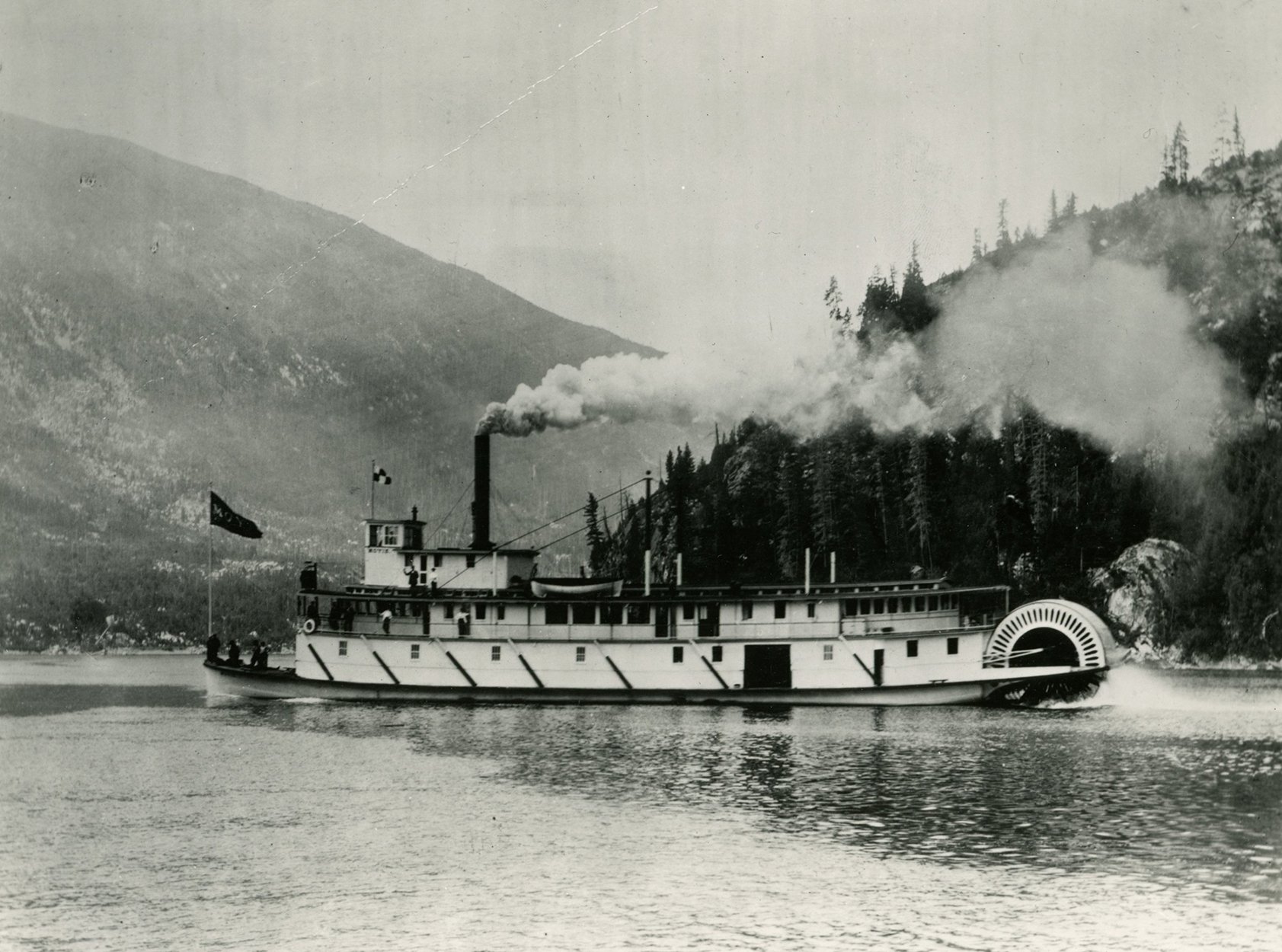

Another great photo of the Minto at work. Ferry travel today just isn’t the same. —Courtesy Canadian Pacific

More years past, Minto steadily continuing her schedule of two round trips a week, except during winter when the busy dowager confined herself to the run between Arrowhead, Nakusp and Carrols, the tug Columbia assuming her duties in lower Arrow Lake due to low water. Fog and Ice were further inconveniences encountered during winter, but her 22 men crew proceeded with few interruptions. “She always managed to get us through,” declared an officer.

Striking sandbars became almost routine and a former master praised her shallow draft: “She could run in a heavy dew.”

Minto had changed little since the day of her launching, so many years before. Although her interior had been renovated, the aging sternwheeler still boasted most of her original fittings and machinery, passengers never failing to marvel at her faded yellow certificate of registry, Number 32. Dated 1896, it was displayed in a glass frame in the forward lounge.

And they’re off! Not really, just the Minto, in the lead, and the S.S. Kuskanook going about their business. What would environmentalists say about those smoke plumes?—Wikipedia

Besides Minto’s legendary cuisine cuisine—“all you can eat for a dollar”— passengers enjoyed the majestic scenery of snow-capped mountain peaks, sparkling water and ruffled greenery. In the Narrows between the upper and lower lakes, Minto charged through the surging current, almost touching the banks on other side, her paddle threshing loudly, tall funnel belching black smoke.

Then there were her ‘ports of call,’ from government wharves, where she unloaded cargo, to clay riverbank where she nudged her bow to pick up a passenger or two.

But more than the scenery, good food and rustic routine, passengers remembered the steamer’s warm hospitality. It was like stepping into the past, away from the hustle of modern everyday modern living. There was little formality on the Minto, travellers enjoying dinner with such popular masters as Capt. Walter Wright and the reminiscences of pipe-smoking first mate and future master, Bob Manning.

This photo by Daphne Hunter shows the Moyie’s salon which would have been similar to that of the Minto. It captures the Old World charm of travel on B.C.’s interior lakes. —www.nelsonkootenaylake.com/

There were exciting times, too, such as the day Minto, under command of her new skipper, Capt. J. Thompson, collided with her Halcyon dock during a storm. Characteristically, she didn’t pause for repairs, the crew attending to her injuries while underway.

Other memorable occasions included the Golden Spike Days festivities at Arrowhead in 1948, when the beloved steamer—the “symbol of the courage and determination that made B.C. what it is today”—was presented a plaque by Revelstoke Kinsmen for 50 years’ dependable service “through storm and fine weather, through flood and low water”.

Many recalled the gala excursions of 30 years before, when Minto and S.S. Kootenay had carried 500 holidayers and two brass bands to St. Leon for a picnic, the last time any of the once-proud fleet had steamed above the Arrow Lakes on the original run.

The historic voyage marked Minto’s 7000th trip.

Minto had been busy during the late ’40s. In 1947 alone, she carried 12,000 passengers. With construction of the Lower Arrow Lake hydro development, her duties increased as she carried men and materials to the project site. At the other end of the scale, she was still her old self, as illustrated by part of one cargo—a ball of knitting yarn.

The paddlewheeler gained international acclaim in 1949 through an article in the Saturday Evening Post, Richard L. Neuberger describing the old lady’s working schedule and surroundings in glowing prose: “The Minto remains the only carrier of mail and freight to those who mine, log and cultivate the shaggy slopes of the Selkirks... Rainbow and Dolly Vardens feel the throttle of Minto’s paddle and mountain sheep and mule deer watch...from the precipitous shore.”

Another passenger, Les Rimes, extolled the breathtaking scenery to be savoured from Minto’s worn decks: “Willows overhanging the beach, then a rock bluff where pines are bent and gnarled, then a leaning farmhouse with a whisper of smoke lazing out, a field of cattle, and orchards red with fruit, low-lying swamp land where bull rushes grow and the ducks make their resting place.

“More farm houses and orchards, then, miles of virgin forest. And, above the passing panorama, the blue mountains.

“Of Minto herself: it was dusk; rain began to fall. A flashlight signal blinked from shore as we continued on our way. We altered course for the deep shadows of the beach. The ship’s searchlight picked the way as we slowly drifted in. The gangplank went down, but nobody came aboard. A man wanted the skipper to mail a letter!”

During another passage, he witnessed a man waving from a deserted beach. Beautifully nosing her into shore, Minto’s master fulfilled the man's request—he wanted to know the time—and calmly proceeded on his way.

But 1954 brought the inevitable. On April 23rd, 93 passengers from every corner of the continent who’d reserved cabins for the occasion, boarded Minto for her last official voyage. H.W. Herridge, MP for Kootenay West, had fought a valiant battle in Ottawa for a reprieve, as had Kalso Slocan MLA Randolph Harding in Victoria, but to no avail.

Minto was too old, she no longer paid her way and, despite heavy public protest, the federal government refused a subsidy.

Minto’s sister, S.S. Moyie, has survived as “the oldest intact passenger sternwheeler in the world”. Designated as a National Historic Site of Canada, she’s on the BC Register of Historic Places, and draws 1000s of visitors annually as a popular museum and tourist site. Precisely what John Nelson had hoped to achieve with the Minto. —Courtesy Canadian Pacific

That afternoon, 200 persons crowded the little dock in Nakusp to wave farewell, as aircraft pilot Dave Duncan flew over twice, dipping his wings in salute, and the motor vessel Beaton whistled goodbye. At arrowhead, 73-year-old John Nelson had erected two signs: “Let us honour the brave pioneers of navigation on scenic Arrow Lakes by making it possible to continue the S.S. Minto’s services,” and, “Au Revoir, Minto”.

At Edgewood, Charles Maynard had erected a sign which read, “Goodbye, old girl—gone but not forgotten—though absent ever dear.” Off lonely Blondin’s Point, Minto whistled salute to the grave of Mrs. Blondin who, until her death, had never missed waving to the ship from the Rocky Point.

When Capt. Manning brought Minto alongside for the last time, passengers headed to shore with their memories and souvenirs, including a life buoy and fire axes, as 100s lined the wharf solemnly. Then they were gone. The next day, work crews began the final cleanup.

Months later, it appeared Minto was to have a new lease of on life when the CPR donated her for, for a dollar and 5 cents (including provincial sales tax), to the Nakusp Chamber of Commerce. At a public meeting, a committee was formed to consider possible uses for the old ship. Among suggestions put forward were a bowling alley, museum and community centre. The following spring, bulldozers cleared a sand foundation on the lake shore above high water in Nakusp.

But, despite the dedicated attempts of history conscious organizations, S.S. Minto had fallen upon hard times. Finally, when funds to preserve her weren’t forthcoming, she was sold for scrap.

And scrapped she’d have been, but for her old friend John Nelson of Galena Bay. He it was who’d painted the signs for her farewell. He’d seen her for the first time in 1904, and for 50 years had watched her ply her rounds. In anguish, he’d watched the ill-fated attempts at preservation. But her sailing to the wreckers had been the last straw.

For $840, he bought her on the basis of where is as is, then paid to have her towed to Galena Bay.

Unfortunately, the wreckers had already ravished her paddle wheel, engines, funnel and brass, but this didn’t deter Nelson, who set to work with hammer, saw and love. From the bones of the old Bonnington he salvaged door and window frames, and lovingly reproduced Minto’s name plate—lost to the wreckers—in his workshop.

“It's a pleasure to do it,” the old man in the officer’s cap with the SS Minto badge told a reporter, adding mournfully, “I'm the only one in the world to do it.”

He’d been blessed with nothing less than a miracle in 1960 when floods floated Minto to the very field he had in mind from the beginning; the receding waters left his prospective museum high and dry. Over the years, the gallant old man invested his savings and devotion into restoring Minto to her former glory, drying her out in the winter and patiently shovelling snow from her weakening decks.

By 1966, 87-year-old John Nelson was battling yet another foe. The High Arrow dam meant that Galena Bay would be flooded. MLA Randolph Harding then took up the defence, urging the provincial government to save the Minto and appoint Mr. Nelson its curator.

Alas, his dream was to be denied. John Nelson died, and his beloved ship was left to his son Walter. Walter tried to interest the provincial and federal governments in saving the ancient steamer, but to no avail. Despite his father's loving attention, the years had taken their toll. When B.C. Hydro offered to move the hulk to higher ground and commissioned a marine surveyor to estimate the cost of transfer and restoration to a museum, his estimate came in at $95,000.

“While I appreciate the hydro company's offer I had to decline it,” said Nelson. “As an individual I simply can't look after her. Snow removal in the winter and vandalism in the summer are just two of the problems I can't cope with.”

Saved for posterity, the S.S. Moyie recalls the heyday of lake boat travel. —Government of Canada

The sad end came at last for S.S. Minto in August 1968 when Hydro workers pumped her dry, then towed her into midstream. There, in the waters she’d known for over half a century, for an incredible 2.5 million miles, Walter Nelson set her ablaze.

Minutes later, a plume of smoke rose 2000 feet over the Columbia River. Then the old sternwheeler’s skeleton, hissing violently, settled beneath the blue waters.

As Capt. Bob Manning had said upon her retirement in 1954, “That's the way an old ship should die—gloriously.”