S.S. Salvage King Made Headlines for 15 Years

“With her holds full of water and possibly abandoned by the underwriters, the 10,000-ton American freighter Golden Harvest is lying at the mercy of North Pacific waves, a hoped-for harvest of the natives living along the rim of the inner Aleutian Islands and the bleak Alaska coast when the seas break her up and distribute the cargo remaining in her holds along the beaches of the northern coast...”

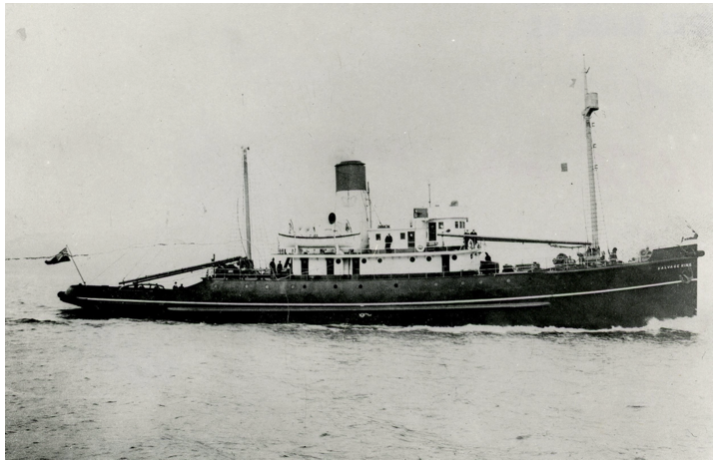

The Victoria-based steam tug Salvage King earned an international reputation for her exploits before her career was cut short during the Second World War. —Vancouver City Archives

It wasn’t often that the mighty steam tug Salvage King had to admit defeat. For 15 years her name achieved almost legendary status in B.C. maritime circles—as fine a working lady as ever secured a bowline.

* * * * *

Poleric, Machaon, Thiepval, Armentieres, Havilah, Eemdyk: the list of the King’s conquests is long and forms an illustrious chapter in provincial maritime lore.

Scottish-built in 1925, the handsome steamer became flagship of the Pacific Salvage Co., Victoria, upon delivery from her builders. With her commissioning, Pacific Salvage had rightfully laid claim to having “the most modern salvage plant, afloat and ashore, in the world”.

Then began a career that was to make headlines repeatedly for 15 exciting years.

The King's first assignment came in November 1925 when the SS Poleric issued a distress signal, reporting that her cargo had shifted. Caught in three cross-winds reaching cyclone force, the 25-year-old Scottish freighter wallowed helplessly, a full cargo of grain and ore and her own slender design threatening imminent destruction. Then her steering gear failed and, powerless and listing 12°, with two men seriously injured, the aging freighter faced the end.

But the King’s Captain J.M. Hewison had other plans.

Steaming to the freighter’s aide at 14 knots, he held Salvage King's bows into the gale hour after hour. Throughout the savage beating, the tug forged onward, ever nearer the stricken merchantman. Finally, on a storming winter evening, her lookout spotted smoke from the Poleris’ funnel. Then it was dark and nothing for the tug to do but stand by until morning.

Aboard the Scotsman, the nightmare continued uninterrupted throughout that wild night. Two of the Lascar seamen had been severely hurt, one with a dislocated hip and fractured thigh bone, the other with broken ribs and head injuries. Dawn, however, brought an improvement in the ship’s fortunes when her crew succeeded in repairing the steering gear and reducing her starboard list slightly.

Later in the day, the tug manoeuvred close in to fire a line on board with rifle and grenade. The first shot landed squarely on the freighter’s deck, only to snap between the bucking ships when Poleris’ crew attempted to secure it to a heavy hawser. But a second shot “placed another line on board and the Salvage King paid out over 1,800 feet of two-inch towing line. After considerable hard work and notable seamanship on the part of the officers of both vessels, the Poleris was brought under tow and progress was made toward port”.

It was during that long hard pull to Victoria that the King proved herself, steadily battling forward although “three distinct seas were running at the same time, a southeast, southwest, and a westerly, all three combining to make towing difficult and playing with the freighter like a cork in a hand-rocked bathtub”.

Throughout the ordeal the protesting Poleric fought like a prisoner bent upon escape from the thin hawser that meant salvation by dipping her starboard rail under waves that rose ever higher and over her hatch combings. Then the plunging ship would “rise almost on end, with mountains of waters running out from under her as she sank again in the troughs”.

But Salvage King wasn’t to be cheated of her first rescue and, finally, she hauled the freighter to Victoria's Ogden Point and nudged her alongside No. 1 Rithet pier. SS Poleric was battered, canted sharply to starboard, most of her crew bruised and exhausted—but she was safe, her injured crewman hospitalized. Upon dockside inspection it was found that the 4000-ton steamer’s hold partitions had collapsed, allowing the grain to shift.

As for the weary Salvage King, a news report concluded: “From first to last the Salvage King stood up to her first real job and has scored a notable triumph and completed the difficult tow under the arduous conditions present...

“Praise for the salvage vessel and for the master and officers of the Poleris, were general this morning, coupled with relief that the stricken freighter escaped from a very tight situation.” Such praise for the King would often be repeated in following years as the powerful tug added one achievement after another to her glowing record. But not all salvage feats took place on the high seas.

One of her more memorable, if less dramatic, successes was the towing of the Dutch freighter Eemdyk from her rocky perch on Bentinck Island in October 1925. This minor maritime mishap in local waters had become tragedy when the city tug Hope capsized while ferrying longshoremen to the stranded ship. Two days later, as a small feet of tugs and private craft scoured the strait for bodies, the Salvage King towed Eemdyk to safety.

Earlier, she’d re-floated the RCN’s HMCS Armentieres in Pipestem Inlet.

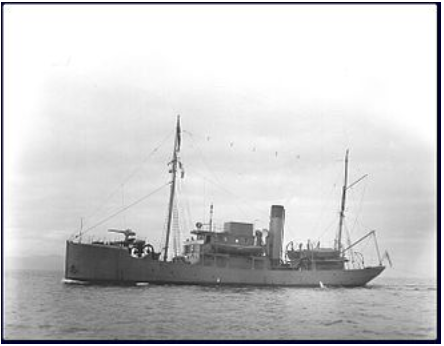

S.S. Salvage King at work alongside the sunken HMCS Armentieres in Pipestem Inlet. —Nauticapedia

The salvage operation had taken 52 days, with the Armentiere’s master, Capt. C.D. Donald on hand as advisor. Thirty years after, he recalled with a chuckle that interesting assignment. A diver, he said, had been lowered to check the sunken ship and to close all openings. But after he’d been in the wreck for some time without having sent or acknowledged any signals from the surface, his shipmates had become worried and quickly drew him up.

When they’d unscrewed his face plate, they’d been amazed to find that not only was he quite well—but quite drunk!

HMCS Armentiere’s Capt. C.D. Donald well remembered the salvaging of his ship. —www.forposteritysake.ca

Laughing, Capt. Donald concluded that the man had found an airlock and, removing his face plate, had sampled the wardroom supplies.

“Unparalleled,” they termed the Salvage King’s towing of the distressed freighter Havilah, in March 1929—another of the deep sea tug’s victories during her 15-year career.

Laden with B.C. lumber and bound for the Japanese furnaces, the American steamer Havilah began her final voyage under her own power but, as if in defiance of the fate that awaited her, experienced one mishap after another. Before she broke down and foundered in a winter gale, her harried crew managed to reach Dutch Harbour in the Aleutian Islands and her Bay City owners engaged the Victoria tug to “finish the job that seemed to be impracticable".

Undaunted by the fact that such a tow in the North Pacific at the stormiest time of the year had never before been attempted, the King slipped from her Inner Harbour berth and steamed northward to take the dying Havilah in tow with “clever navigator and successful salvor” Captain Hewison on her bridge.

Despite heavy seas all the way, she reached Dutch Harbor in eight days and, within hours, was heading back to sea with the freighter waddling astern.

After 26 days and 2,700 miles, the tug triumphantly steamed into harbour at Osaka, the Havilah, jammed with four million feet of lumber, sagging dejectedly at the end of her hawser.

But the history-making voyage hadn't been an easy one. Pacific Salvage Co. manager A.C. Burdick stated that, at one stage, the King herself had been in serious difficulties when seas cascading over her decks threatened to smash through her skylights and flood her engine room, a threat averted only by lashing tarpaulins over the skylights.

Then her steam winches and deck gear became encrusted with ice, adding tons of extra weight which made the fight to keep pointing her nose into each onrushing sea even more challenging.

But throughout that tempestuous haul she’d kept her towline taut and when at last she dropped anchor in the Japanese port, not a single stack of lumber had been lost of Havilah's cargo. Upon the tug's return, she was met off William Head quarantine station by the company steamer Salvage Queen, company officials and newsmen. Then it was into the Inner Harbour to whistles and cheers from ships in port and a large crowd assembled on the wharf, among them news photographers and newsreel cameraman who clicked shutters and shot reels of film.

An obviously tired Capt. Hewison recalled the harrowing voyage: the spray which “froze immediately it touched the deck,” the 80-mile-an-hour hurricane, and the old Havilah’s cantankerous steering which broke down at least once every 24 hours, making it necessary for both ships to heave to in towering seas.

Always, at the height of each storm, there had been the threat that the Havilah’s cargo would break loose and pull the freighter over with it. But, somehow, she’d recovered each time and, ever so slowly, the little convoy proceeded towards Japan.

Until late one night when Havilah wirelessed that her crew was abandoning ship.

“It seemed impossible that she could be sinking," said Hewison, “but when I went out on to the after deck [where] in the light of the moon, through the snow and sleet and great waves, I could catch glimpses of the freighter, I knew that the message was about right.

“She was listing badly over and the deck load looked as if it might be tossed at any moment.

“Another SOS came saying that the situation with urgent, so, taking their advice, I ordered the men to stand by the towline with the acetylene torches to be ready to cut the cable if the Havilah should plunge. That would have been a job for, if it was not done quickly, the King would have been pulled down to the bottom with the freighter.

Conditions were like this for several hours, the [freighter’s] crew working all the time at best as best they could, trying to lash the deck load. They did lash it, and made it more secure than it was when we left Dutch Harbour.”

When the weather improved—briefly—the tow proceeded.

In all, the ships endured 16 gales over a total of nine straight days during that epic voyage. The most nerve-wracking ordeal was the Havilah’s steering gear which “went out of commission regularly and the unwieldy freighter would swerve and shoot out from under our path, taxing the strength of the cable to the utmost and endangering the lives of the men aboard the King who were working near the line.

“Time and again she would swerve and more than once we thought she was gone. But by some strange luck she always came back and never did that towline break or even split."

Once at Osaka, Salvage King’s job was officially done. However, the Havilah’s master implored Capt. Hewison to continue the tow a further 500 miles to Yokohama. Even when the tugboat captain purposely submitted a high bill in hopes of avoiding the assignment and heading home, Havilah’s skipper insisted upon his doing the job. He and his men, he said, didn't fear for their lives when “the Salvage King was in front of them".

After the Havilah triumph had come the unsuccessful attempt at rescuing the Golden Forest, adrift in the North Pacific with a gashed hull. The American freighter’s final voyage had been jinxed from the time she cleared San Francisco bound for the Orient with a full, unspecified, cargo.

The first mishap had occurred when an officer developed blood poisoning, requiring the ship to alter course and rendezvous with a US Coast Guard cutter at Dutch Harbour. Then she struck bottom on Avatanak Island, near Unimak Pass in the Aleutians; at first it seemed that she’d escaped unharmed and she was re-floated without undue difficulty.

But, while continuing on to Dutch Harbour for a damage survey, the Harvest was slowed by a stream of water entering her ruptured hull, and her master was forced to beach her at Akutan Harbour. There, the Salvage King met her to begin towing her to Esquimalt.

Again, her troubles had seemed about over when 1900 tons of cargo were easily removed to another ship, her bottom patched. However, during the lengthy voyage to Esquimalt astern of the Salvage King, ill luck struck again when the disabled freighter grounded a second time in Shelsheiliko Straiht, between Kodiak Island and the Alaskan peninsula.

And there the Golden Forest was left to the mercy of the North Pacific, her crew and senior service officials returning to Victoria aboard the King to consult with superiors as to whether an attempt would be made to remove the ship’s cargo, valued at $100,000.

Salvors had retreated, explained Manager Burdick because of “the position of the ship, far out of touch with communication of any kind and exposed to the whole sweep of the Pacific”.

It would require a lot of mature consideration before such a hazardous enterprise could be initiated, particularly at that time of year, he said.

But Salvage King’s failures were few and far between, her victories many and hard-won. Then she was gone from her home waters to answer the call of war, assigned by the Admiralty to salvage operations in the beleaguered waters of Great Britain. In January 1941, it was reported that the gallant Victoria lady had herself become a casually in the Orkney Islands while in the performance of her duty.

Capt. Hewison was gone, too, having died 10 months before while serving as Salvage Master.

How ironic that the King died as the result of running aground during a storm, a court martial ruling that “this valuable vessel was grossly and wantonly thrown away by negligence on the part of the accused so bad as to be unbelievable”.

Her 35-man crew had been rescued but attempts at salvage failed, only some of her vital gear being retrieved by fishermen. She was later broken up for scrap as she lay, her rusted boilers remain fast on the rocks at the Ness of Duncansby, 84 years later.

Throughout the Pacific Northwest, and beyond, mariners had mourned the loss of the “remarkable little boat” that had so often made maritime history: SS Salvage King.

Another view of the hardy little Armentieres that survived shipwreck to continue a lengthy career as naval and fisheries vessel, then as a tugboat.—Wikipedia