The Amazing Career of HMCS Gatineau

I’ve written before how, as the son of a career Royal Canadian Navy man, my first collection as a nine-year-old was my father’s kit. He gave me everything but his tools and his medals. (I still have them and his medals—and a whole lot more—by the way.)

By the time I was in my 20’s I was deep into writing about British Columbia and Canadian history, including, of course, stories about the RCN.

But until my first visit to the Royston booming grounds breakwater, which was made up of derelict ships, I had no idea that one of the RCN’s most illustrious veterans was among what I came to term the Royston death-watch which was composed of the hulks of sailing ships, warships, tugboats and a whaler.

The first HMCS Gatineau, the former HMS Express. —Esquimalt Naval Museum and Wikipedia

Alas, there was little to see of what had been HMCS Gatineau whose career began in 1934 as the Royal Navy’s HMS Express. It was a sad end for such a courageous ship with so many battle ribbons.

* * * * *

There have been two HMCS Gatineau(s) in the Royal Canadian Navy. The first, an E-class mine-laying destroyer and the subject of today’s Chronicle, had her first taste of adventure when she was attached to the Mediterranean Fleet, 1935-36, during the Abyssinian Crisis (Italy’s invasion of the African nation). Then she was off to Spanish waters to enforce the arms blockade imposed by Britain and France during the Spanish Civil War of 1946-37.

These were just a taste of what was to come in September 1939—the Second World War.

Here’s her official history as HMS Expess and HMCS Gatineau courtesy of the Esquimalt Naval Museum:

HMS Express, pennants H-61, was built on the Tyne by Swan Hunter and engined by the Wallsend Slipway. She was laid down on 24 March, 1933, launched on 29 May, 1934 and commissioned on 2 November of the same year. She served in the Fifth Destroyer Flotilla with the Home Fleet until 1939.

Just before war broke out, she had been fitted for mine-laying and on 9 September, 1939, she and HMS Esk, a sister ship, laid the first British offensive mine field of the war in the Heligoland Bight. On another mine-laying operation off the Dutch coast on 31 August, 1940, she, Esk and Ivanhoe all struck German mines before they could lay their own.

Express was severely damaged and was towed back to the Humber for repairs, but the other two destroyers were sunk.

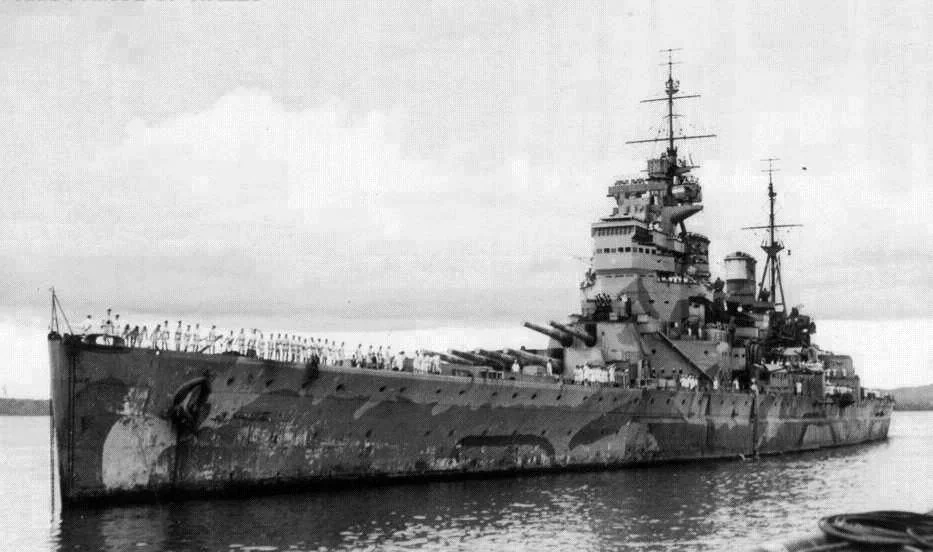

The sinking of the British battleship Prince of Wales (above) and the battlecruiser Repulse by Japanese aircraft off the coast of Malaysia, Dec. 10, 1941, was one of the most historically significant naval engagements of the Second World War. —Wikipedia

HMS Express rescuing survivors of the sinking HMS Prince of Wales. —

Photo by Abrahams, H J (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, from the collections of the Imperial War Museums, Public Domain

In commission again the following year, she joined the Eastern Fleet on its formation. She was among the destroyers escorting HM Ships Prince of Wales and Repulse when they sailed from Singapore on 8 December, 1941. When the two heavy ships were sunk on the 10th, Express went alongside the slowly capsizing Prince of Wales and took off most of her crew dry-shod[!], staying until the last possible moment.

As the [Prince of Wales] went over, her bilge keel fouled Express’, lifting her and damaging her slightly – she had to go full astern on her engines to get clear.

In late 1942 the Canadian cabinet asked Britain for the loan of eight destroyers to reinforce the escort groups on the North Atlantic convoy routes. The Admiralty responded with the gift of six of which Express was one. They had already begun to refit her for escort duties and it only remained to rename her Gatineau after the river flowing into the Ottawa and to provide her with a Canadian crew.

The river, in turn, took its name from a French fur trader and civic official, Nicholas Gatineau, who developed it as a trade route that took him around Iroquois territory safely to the Hurons’ hunting grounds. He disappeared in 1683 – according to rumour he was drowned in the river.

HMCS Gatineau was commissioned into the Canadian fleet on 3 June, 1943, and sailed from the United Kingdom on 2 July as Senior Officer of Escort Group C-2 escorting Convoy ON-191. She quickly settled into the routine of the “Newfie-Derry run” – the work of the Mid-Ocean Escort Force plying between St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Londonderry in Northern Ireland.

The U-boats, badly beaten early in the year, stayed away from the North Atlantic convoys until September.

Gatineau sailed on 15 September in charge of the escort of ON-202 which, in company with ONS-18, was beset by [21] U-boats. Of particular importance in this convoy battle is the fact that this “wolf-pack” was armed with acoustic torpedoes (called GNATS by the Allies) for use against escort vessels.

The U-boats made contact with the convoy on the evening of the 19th and the running fight continued for five days and nights into the early morning of the 24th. HMS Lagan was the first to become a casualty to the GNAT when she was damaged at 0303 on the morning of 20 September, but U-341 had already been sunk by an aircraft.

HMCS St. Croix (one of the ex-American “four-stacker” destroyers) and HMS Polyanthus, corvette, were sunk the same evening.

Meanwhile U-338 had been accounted for by another aircraft. On 22 September, HMS Keppel sank U-229 and the same night HMS Itchen was sunk, taking to the bottom all but two of her own ship’s company, all but one of the survivors from St. Croix and the only man picked up from Polyanthus.

Also sunk in the action were six merchant ships so that the final score was three U-boats sunk for a loss of three escort vessels sunk and one damaged and six merchantmen sunk.

The U-boats found their new weapon no great advantage – they had got a bloody nose using it and on the day Itchen was sunk, barely two days after its first use on Lagan, the Admiralty made a signal giving instructions for effective counter-measures.

Gatineau had been slightly damaged by her own depth-charges in the action and had to be hauled out at Bay Bulls for repairs to her stern glands.

Then, in mid-November, after four more passages across the Atlantic, she was sent to Halifax dockyard to be fitted with heating apparatus to make her more comfortable for her crew in winter. This was her first visit to a Canadian port since Newfoundland was a crown colony at that time.

She rejoined C-2 group, but was no longer Senior Officer, and after an east-bound convoy she found the group allocated to “Support” duties. This meant it joined a convoy in addition to its close escort and gave extra protection through the more dangerous parts of its passage.

U-48, the most successful German submarine of the Second World War. —U-boat.net

They sometimes spent even longer at sea at a stretch because the ships would sail from Londonderry (where C-2 was based) with a west-bound convoy, accompany it for about two-days, transfer to an east-bound convoy for a day, then to a west-bound again and so on, fuelling from tankers in the convoys as it became necessary.

The Senior Officer of a Support Group had greater freedom of action than he would if he were in command of the close escort because he could leave the convoy, if there were no immediate danger, to follow a promising scent.

Just such a case occurred in March, 1944 when Gatineau made contact with a U-boat while supporting Convoy HX-280. This led to a “hunt to exhaustion” which lasted from 1000 on 5 March to 1830 on the 6th. Gatineau herself had to leave the hunt during the night because she was short of boiler feed-water, but her contact led to the sinking of U-744 by the other ships of the group.

Even after having about [200] depth-charges and three patterns each from squid and hedgehog dropped on her, the U-boat was little damaged and was prepared to fight it out with her guns when she broke surface, but she expected to find only two escorts waiting for her.

As it was she was deluged with shell from five ships and never got a man to her guns. She surrendered almost at once. It was only her air supply that had been exhausted.

At the end of April, 1944, Gatineau, along with the other destroyers in the Mid-Ocean Escort Force, was withdrawn from the Atlantic. She was allocated to Escort Group No. 11, consisting entirely of Canadian “River” Class destroyers, for duty in the English Channel for the landings on the Norman coast [D-Day].

The work was mostly patrolling the supply lines to protect them against submarines. HMC Ships Ottawa (Senior Officer) and Kootenay and HMS Statice distinguished themselves by sinking a U-boat on 7 July, but Gatineau was elsewhere at the time. Just a few days later her boilers blew several tubes and it was decided to send her home for a refit.

This kept her in Halifax from August, 1944 to February, 1945, and it was 1 May, a week before VE-Day, before she was ready to sail again from Londonderry for operations with EG-11.

During that week she carried out patrols in the channel. On 12 May the group carried out Operation “Nestegg” the reoccupation of the Channel Islands. They escorted the transports that landed British troops on the islands and carried out patrols off-shore afterwards. It was not clear yet whether all U-boats had heard of the end of hostilities so EG-11 had more patrols and two channel convoys to escort before they sailed northward for Londonderry on 23 May.

On the 30th they called at Greenock, picked up homeward-bound Canadian naval personnel and sailed for home. On 6 June they arrived in Halifax and EG-11 was disbanded.

Gatineau’s first peace-time duty was to act as transport – she paid another call to Greenock to bring Canadians home taking from 22 June to 10 July for the two-way passage. Then she was allocated to HMCS Royal Roads, the Royal Canadian Naval College, for sea-training duties, and sailed for the west coast on 11 August, 1945, arriving 5 September at Esquimalt.

She commenced a refit for training work but before it was complete HMCS Crescent, a more modern ship, became available and Gatineau was paid off on 10 January, 1946.

In March 1947, when the fleet was being reduced, Gatineau was declared surplus and later the same year she was sold and broken up.

* * * * *

All that drama in just 1400 words; it’s an official summary, after all, not a novel, but, curiously, there’s no mention of her role in the monumental Dunkirk evacuation although the rest is there if only briefly:

―Blockade duties in the Abyssian Crisis and Spanish Civil War

―Laying the first offensive Allied mine field of the Second World War

―Her removal of 100s of British soldiers during the Dunkirk evacuation, May 26-June 4, 1940

―Her escape from being sunk by a German mine that blew off her bow and required a year in dry dock to repair

―Her rescue of almost 1000 survivors from the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales when it was sunk off Malaya by the Japanese.

―Her convoy escort duties on the legendary “Newfie-Derry” and Triangle runs after being transferred to the RCN

―Her sinking a U-boat and helping to destroy a second

―Her escape from being sunk by her own depth-charges

―Her security duties in the English Channel leading up to D-Day

―Her participation in the liberation of the Channel Islands

* * * * *

When I first began exploring the wrecks that formed the Royston breakwater in the early 1970s, thanks to the owner, Crown Zellerbach having commissioned me to research and write their stories for a newsletter, several of the wrecks were partially intact.

Not so poor Gatineau who’d been all but buried by rock-fill.

Some of the Royston wrecks, such as the Forest Friend, were still partially intact in the early 1970’s; not so HMCS Gatineau, sad to say. —Author’s Collection

* * * * *

The second HMCS Gatineau, a Restigouce-class destroyer, served n the RCN and later the Canadian Armed Forces during the Cold War, 1959-1996. She was sold for scrapping in 2009 —US Navy photo

* * * * *

PS: This letter from reader Brian Davis:

“Dear Mr. Patterson:

Interesting to read about the HMCS Gatineau in today’s publication (Chronicles, January 26). My uncle Raymond Alec Ford served on the Gatineau from 1944-1945. He was born in Nanaimo but grew up in Duncan. Most of his adult life was spent in Port Alberni. I look forward to reading more about the Gatineau.

Ray joined the Royal Canadian Navy on May 25, 1942. He served on the HMCS Mastodon from April 9, 1943 - January 20, 1944 and was at sea for 52 days. He was discharged from the Navy on October 16, 1945.

The Gatineau...was under refit in Halifax when Ray joined it and left February 16, 1945 for Tobermory, Scotland.

This was the home to the Royal Navy training base. On completion of work-op it was deployed on convoy defence in UK coastal waters because increased U-Boat attacks were being carried out by Schnorkel fitted submarines. VE day came on May 7, 1945 so the HMCS Gatineau returned to Halifax, arriving in June.

In August it was transferred to Esquimalt, British Columbia. In 1947 it was sold to Capital Iron and Steel Metals in Victoria. In 1956 it was scuttled for use as part of a breakwater in Royston, B.C.”

* * * * *

Thank you, Brian, for giving my post a personal touch by with your reference to your uncle, Ray Ford.