The Case of the Wrong Saddlebags

One of my favourite pioneer storytellers, D.W. Higgins, whom we’ve met before in the Chronicles (Victoria’s House of Horrors and My First Christmas in Victoria), wrote two books during his retirement.

Both The Mystic Spring and Passing of a Race were based upon a series of articles he’d written for the Daily Colonist about his 40-year career as a journalist and newspaper editor during the province’s eventful founding. In the latter book, published in1905, he tells a fascinating tale of a brutal robbery and murder in B.C.’s Cariboo gold fields.

A crime that left him wondering, half a lifetime later, about a man who’d astonished one and all by going, not just calmly, but almost willingly, so it seemed, to the scaffold...

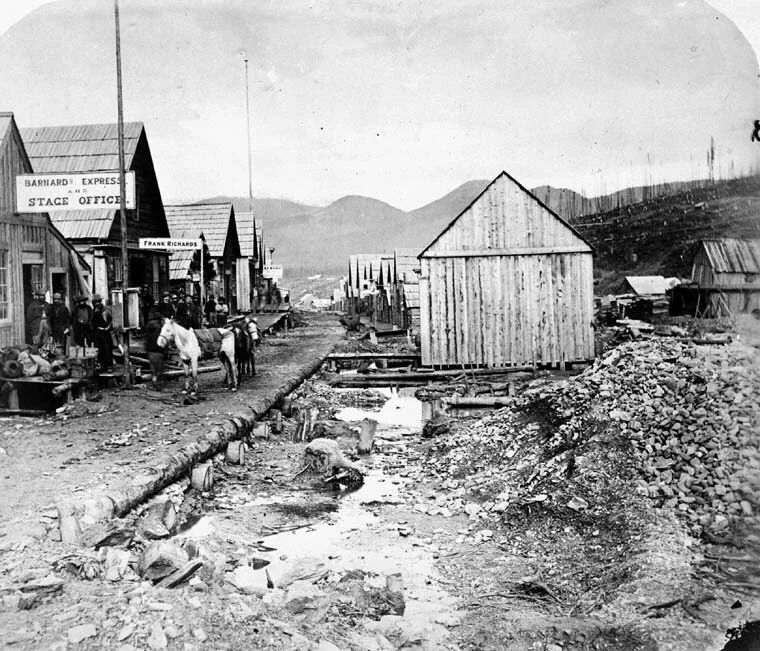

‘Downtown’ Barkerville. Of the 10s of 1000s of adventurers from around the world who participated in the Cariboo gold rush, there had to be those who never meant to seek their fortunate by hard work but who chose instead to prey upon their fellows. Thanks to the newly created B.C. Provincial Police and the legendary ‘Hanging’ Judge Begbie, however, serious crime was kept to a minimum. —Wikipedia photo

William Armitage, as he called himself then, had earlier used the name George Storm, but neither was the real name of this mystery man whose noble family, Higgins had been told privately and on the best of authority, dated back to William the Conqueror.

In fact, “it was more than suspected that [he] was closely related to a duke...” How could a man of such illustrious background find himself, half a world from home, facing a hangman’s noose in the Cariboo.

Yes, popular writing styles have changed since D.W. Higgins’s day, so his prose is a tad florid by today’s standards. But the fact remains that he’s a superb storyteller who was blessed, as a career journalist, politicians and civic leader, with an sometimes exclusive inside track on many of the events and characters he writes about. In fact, but for D.W. Higgins, most of the historic B.C. dramas he wrote about at length would be nothing more to us today than vague and teasing snippets in old newspapers...

* * * * *

Early in the month of May, 1845, a British steamship sailed from the port of Southampton bound for the West Indies. Amongst her 300 or 400 passengers were a young couple who bore the name of Mr. And Mrs. George Storm. They gave out that they had been recently married, and from their appearance they were well-bred and well connected.

The pretty bride, who was little more than a girl, was exceedingly pleasant in her manners, and made friends of all with whom she came in contact on board. Among the acquaintances they made was a middle-aged gentleman named William Stephenson. He was an Englishman, and having been to California, was on the way back to look after some mines that he owned there

As Mr. And Mrs. Storm were also bound to California, they found the information which Mr. Stephenson possessed of the country most valuable. So the three were thrown much together, and by the time the steamer reached the isthmus of Darien they had become fast friends, and formed plans for the future.

In due course, the passengers crossed the Isthmus and embarked on a steamer which landed them safely in San Francisco.

Here Mr. Stephenson learned that the bank in which he had on deposit a large sum of money had failed, and a project which he had in view for the advancement of his new-found friends could not be carried out.

The Storms were naturally greatly disappointed at the result, as they were not overburdened with means, and, after some days they departed for the interior of the State, where Storm said he would try his luck at the diggings. They took leave of each other, Stephenson remaining at San Francisco to recover what he could from the wreck. A fact which struck Stephenson as strange was that the Storms had not a single letter of introduction, nor did they impart any information as to their connections or antecedents, beyond the fact that their match was a runaway one and that the girl’s friends objected to her marrying Storm.

But, as they were very nice, and apparently respectable, Mr. Stephenson took them entirely into his confidence and lent Storm a considerable sum of money from his depleted store. He departed from them with regret, for he well knew the temptations to which they would be subjected in the mining towns.

Several years passed, during which time Stephenson did not hear from his steamship acquaintances.

He at last gave up hope of ever meeting them and, although he often wondered what had become of them, they gradually faded from his mind.

In 1862 the Cariboo gold fever broke out, and early in that year Mr. Stephenson joined in the rush to the new gold fields. The path through the then unexplored country was difficult and dangerous. Thousands walked every foot of the way and reached Williams Creek, where the richest deposits were found, weary and worn from the hardships they had gone through.

Stephenson was so fortunate as to secure a claim upon one of the richest bars on the creek. Near this bar “Old Man” Diller, Hard Curry, Bill Abbott, Jim Loring, John Kurtz, Bill Cunningham, John Adams, Wm. Farron. John A. Cameron, Bob Stevenson, and a host of others whose names will ever live in history as the possessors of rich claims in Cariboo, were located. They washed out hundreds of thousands of dollars in a single season. Frequently as high as five thousand dollars was obtained from a single bucket. When Abbott one evening staked $5000 on a single at poker, and was remonstrated with for his foolishness, he replied:

“Oh, pshaw! It’s only a single bucket. There’s 500,000 such buckets still in the claim.”

The day came when poor old Abbott walked the streets of a British Columbia town in search of a man who would lend him the wherewithal for a meal, and found him not. Of the 100s who had fattened at his board in the days of his affluence, not one offered to help him when he became poor again. Is this not the way of the world? I do not say that Abbott died of want; but I do know that the men who helped him in his later days were not those who fed and drank at his expense when he rolled in gold.

Abbott’s fate was that of nearly all the men who made big money in Cariboo. Cameron carried his earnings to Eastern Canada. He had $175,000. This large sum he lost in a few years in bad speculations. Twenty-five years later he returned to the scene of his former success and opened a little eating-house. One day, while supplying a customer, he dropped dead. Old man Diller was almost the only one who held on to his talent and made more. He settled down in Pennsylvania, where he invested in real estate and died worth an enormous sum. Bob Stevenson lost his wealth in trying to add to it. He is still trying in Granite Creek to strike another Williams Creek.

Our steamship acquaintance, Stephenson, from whom I have obtained much of the material for this narrative, is still alive and resides in California, old, hale and hearty, and wealthy,. He told me that in a single season he made $56,000 on Williams Creek, and that he sold out to his partners at the close of the year for $10,000 more. Like Diller, he kept his pile, and added to it.

A day or two after Stephenson had disposed of his claim, and was popularly supposed to have a large sum in his cabin, he strolled into a gambling house at Barkerville.

Gathered in the house were many evil-looking men and women. The scene was dimly lighted with kerosene lamps. On the tables were cards, dice and faro-banks, and a billiard table in the centre of the room was utilized for the purpose of keno. A continual stream of miners and business men were entering and departing, after trying their luck at the different games or imbibing at the bar.

Now and again the voice of the dealers would be heard, shouting, “Make your game, gentlemen,” or, “Game’s made, gentlemen, roll.” The music from a piano and a fiddle, the clanking of glasses and the popping of corks added to the din. In one corner might be seen a miner, who had parted on the green cloth with his week’s earnings, bewailing his hard luck; and in another corner stood a prospector, who was exhibiting to the astonished gaze of his friends the glorious prospect he had obtained from a new discovery.

In the middle of the room a painted lady with a glass of Oh-be-Joyful in her hand was essaying an Irish lilt to the accompaniment of a mouth-organ between the lips of a besotted miner. On the sidewalk two men engaged in a bout of fisticuffs, to the intense delight of a crowd of by-standers. Across the street a cocking-main was in full swing, and numerous posters announced that on the following day there would be a prize fight, with bare knuckles, between George Wilson, the English champion, and “the great California Unknown.” The betting was heavily in favour of Wilson.

“You see,” said one of Wilson’s backers, “the California fellow’s got the most science, but George has got one thing that gives him a big advantage. He’s got the best of the fight before he strikes a blow.”

Stephenson was anxious to know in what the advantage possessed by Wilson consisted, and asked the man to explain.

“Why,” said the fellow, “George has got a cock-eye. Now, if you stand up to fight a man you never want to take your eye off his’n. If you do, you’re a goner. How can you follow the movements of a man with a swivel-eye? You can’t do it. He’ll belt you all about the ring, while you’re searching for his optic.”

Convinced by the reasoning of Wilson’s backer, Stephenson bet $500 on the man with the cross-eye, who lost the fight in five rounds.

Attracted by a sound of revelry, Stephenson next entered a long hall in which a number of miners and others were engaged in wooing the favour of Terpsichore with a number of highly perfumed and gorgeously arrayed females. They were known as hurdy-gurdy girls. These representatives of the goddess of dancing were imported from California expressly to serve as partners for the miners of Cariboo. All were not too young or beautiful, but they were gracious and never refused to drink when asked. Indeed, they were expected to urge their partners to treat them at the close of each dance, and as the broad light of day often streamed into the hall before shutting-up time came, the amount of liquor consumed on the premises at the rate of 50 cents per drink must have been very great.

As he stood gazing at the whirling figures Stephenson witnessed a dastardly act.

A ruffian who had been disappointed in getting the hand of one of the painted and bedizened creatures, and was madly jealous as a result, watched his opportunity, when he fancied he was not observed, and, striking her violently in the face ran toward the door. The woman screamed and would have fallen had not the strong arm of Stephenson caught her form and laid her gently on the floor.

A crowd gathered at once, and chase was made for the assailant, who was soon overtaken and severely beaten for his brutality. In the meantime Stephenson busied himself in restoring the unfortunate woman to consciousness. His efforts were soon rewarded, and he had the satisfaction of seeing her open her eyes and ask to be taken to her room. She had a bad bruise on he face, and as she was assisted to her feet the woman gazed long and earnestly at Stephenson.

“Where—where have I seen you before? Was it in England? Or was it in California? No, it cannot be. Surely you are not Mr. Stephenson? You are not the gentleman I met on the Southampton boat?”

“My name is Stephenson,” he replied, “but I cannot recall that we ever met before.”

“Am I so changed that you do not know me?” the wretched woman asked. “Do you not remember George Storm and his wife?”

“Yes—yes—but do not tell me that you are Mrs. Storm!”

“I am that lost woman,” she cried, as she burst into a flood of tears.

“And where is your husband,” Stephenson asked, with emotion.

“He is here—in this camp.”

“And does he know that you,” he hesitated for a moment for a word, not wishing to wound the woman’s feelings, and then added, “that you are here?”

“Yes, but do not blame him. We were reduced to great straits. My baby died, and my friends at home would not help us, so—and so—you know the rest.”

Again the poor woman wept, and Stephenson could scarcely refrain from mingling his own tears with hers.

With a great effort he restrained himself, and having arranged for a surgeon to attend her injury, he left her, promising to return on the morrow, mentally resolving to do all in his power to rescue her from her forlorn condition.

Stephenson followed the winding of the creek to his cabin, which was situated about a mile above Barkerville. The night was intensely dark. As he neared his place, he observed a light within. He approached a window and peered cautiously into the front room, the blind of which was raised, and plainly saw the figure of a tall man standing by the side of the bunk, in the act of raising one of the mattresses, apparently searching for valuables. Stephenson turned for the purpose of raising an alarm, when he became conscious of the presence of another man, who advanced from the shadow of the cabin and dealt him a severe blow on the head.

The victim fell at once, and lay where he fell until early morning, when he was discovered by some miners on their way to work, and his injuries, which were quite severe, were attended to by Dr. Black, then a noted practitioner on William Creek. The doctor decided that the patient had been sandbagged, and ordered his removal to the hospital, where several days elapsed before he recovered sufficiently to tell how he received the hurt.

By that time, identification of the robbers was impossible, and no steps were ever taken to apprehend them.

They got very little for their crime, as their victim had, providentially, deposited nearly all his wealth in the bank. As soon as Stephenson obtained his discharge from the hospital, he repaired to the dance hall and enquired for Mrs. Storm, who was known to the inmates as Bella Armitage. To his profound grief, he learned that she had left the creek the day after the assault, and that a man calling himself her husband, had gone with her...

Stephenson lingered about Barkerville until the better part of July of the following year [1863], hoping to hear from a party of prospectors under John Rose, whom he had sent out the previous fall, and who had not been heard from since their departure. When news did come in it was of the most dismal character. Rose and his party had died of exposure on one of the unexplored creeks, and their bodies were buried where they were found.

Stephenson immediately left Cariboo and travelled by easy stages toward the lower country. He was accompanied by several other miners, who, having made their pile, were desirous of reaching civilization by the speediest and safest means. As the road was believed to be infested with desperate men who had failed to win gold at the diggings, the miners kept closely together, and were duly armed.

On their way out the party fell in with a young man named Tom Clegg, a clerk in the employ of E.T. Dodge & Co., merchants. Clegg,

who was on a collecting tour, was known to have in his possession a very large sum of money, which he carried in saddlebags on his horse, a large, powerful animal. He was accompanied by a Captain Taylor, who belonged to some place on he Sound. Taylor rode a mule. When Taylor and Clegg fell in with the miners, they expressed great pleasure in the protection afforded, and agreed to keep close by them. The party reached the 150-Mile-Post, a wayside inn, in good shape. But there they fell to drinking and carousing, and when day dawned, neither Clegg nor Taylor was in a fit condition to travel, so the others started without them.

Cleg and Taylor followed about an hour later, having changed animals at the Post, Taylor riding the horse with the gold-laden saddlebags, and Clegg bestriding the mule, which carried no treasure.

A short distance below the Post, two men were seen ahead. As the travellers approached the men separated, one crossing to one side and the other to the other side of the road, as if to the let the horsemen pass between them. When the horsemen came opposite them, each footman grasped a bridle and began shooting. Taylor’s horse took fright, reared and broke loose, dashing the man who held him to the ground and got clear off, darting along the road at great speed.

Clegg leaped from his mule, and seized the man who held his horse’s bridle. He was getting the best of the highwayman, when the man who had tried to stop Taylor’s horse came to the assistance of his pal, and shot Clegg dead. The robbers then cut the saddlebags from the mule’s back, under the impression that they contained the gold, and, plunging into the thicket, disappeared.

The murderers were seen the next day by William Humphrey, now of Victoria, who was driving a light wagon along the road. While following the trail of the highwaymen through the bush, the Indian trackers came upon the saddlebags. They had been cut open, and the contents, a bundle of papers, and a suit of underclothes, lay on the ground.

What must have been the feeling of the robbers, when it dawned upon them that they had taken the life of a fellow being, and imperilled their own lives, for so paltry a booty as the wrong saddlebags contained, may be imagined.

Mr. Humphrey told a party of the robbers’ whereabouts, and one, who gave the name of Robert [sic] Armitage, was caught in the valley of the Bonaparte.

The other disappeared, and was seen no more alive. For a long time it was feared he had got out of the country; but one morning a farmer on the North Thompson, while watering his stock, saw on one of the bars what he at first took to be a bundle of clothes, but which upon closer examination, proved to be the body of the missing highwayman. The survivor was committed for trial before that judicial terror, Judge Begbie.

(I’m going to interrupt here to give more details of the robbery and the immediate aftermath as reported by the Lillooet correspondent in the Aug. 28, 1863 edition of The British Colonist: Committed two days earlier on a hill near Murphy’s road house at the 141-mile post, it was yet “another of the most horrid cold-blooded murders which has to swell the list of many hitherto perpetrated,” raged the Victoria newspaper.

(Popular Tom Clegg and Capt. Joe Taylor were in the act of passing two men on foot, as described by Higgins, when, without a word, they seized the reins of the horse and mule and began shooting. Clegg, hit behind the ears and in the body, was killed instantly but Taylor’s spirited mount—actually Clegg’s large bay—its chest grazed by a bullet, reared and bolted. Taylor, who was unhurt, drew his own revolver and fired at the robber as he was being dragged along the ground. Taylor was sure he hit him in the side and the man let go, leaving Taylor struggling to regain control of his horse. By the time he’d wheeled about and returned to Clegg, the robbers had vanished, penniless, in the dense woods bordering the wagon road. Trackers later confirmed that one of them had been hit when they found a bloodied bowie knife and revolver.

(Now: back to Higgins.—TW)

Stephenson, having convoyed his gold to Yale, placed it in the hands of Billy Ballou, the pioneer expressman, for transmission to the Bank of British North America at Victoria. Leaving the express office, he walked slowly along the front street, and almost the first person he met was Mrs. Storm, alias Armitage. She had recovered from the effects of the cruel blow, not a trace being noticeable, and with her face divested of the paint, she looked like her former self. Accosting him she said, imploringly:

“Oh, Mr. Stephenson, I am so glad to have met you, for I am in great trouble, and need your help. I have just received a letter from Mr. Storm. He is in prison in Lillooet. He is charged with the murder and robbery of a man on the Cariboo wagon road. He is without money and friends and unless he can get some money, he will surely be hanged. Will you help him?

“In the past you have done much for us. Will you aid us once again? In God’s name, I implore you to return to Lillooet and see if something cannot be done to save him. I know that he has been a bad man and has done much that was wrong; but I can never forget that he is my husband—and think of the disgrace!

“I gave him all the love of a young and pure heart, and I forgive him freely for the wrongs he has heaped upon me and the misery he has caused me.

‘Hanging’ Judge Matthew Begbie lived up to his reputation by sentencing Armitage to death. —Wikipedia

“Will you—oh, will you, Mr. Stephenson, befriend us once more? Will you return to Lillooet and give him this letter?

Stephenson told me, many years afterwards, that he at first declined to accede to the unhappy woman’s appeal; but she was so persistent and so pathetic in her prayer that he yielded at last, and, after providing for her comfort at one of the hotels, he left by the first stage for the scene of the trial, arriving at Lillooet the day before the court opened.

The little town was uncomfortably filled with jurors and witnesses, and a few lawyers, who accompanied the judge on circuit. Mr. Stephenson had an opportunity of seeing the Chief Justice for the first time as he took his seat on the bench to preside at the assize.

Arrayed in wig and gown, [Judge Matthew Begbie] presented a majestic appearance.

He was far above the average height, being six feet four in his socks. His figure was as straight as an arrow, his features, when in repose, were stern and somewhat forbidding; his brown eyes were expressive and thoughtful; his hair was just then turning from black to grey, and his face was adorned with carefully trimmed moustache and whiskers. His bearing was that of a judge who under any and all circumstances would discharge his duty as he understood it.

This was the man who, by the sheer force of his iron will and overpowering intellect, swept all before him. A giant among pigmies, he subdued the most turbulent ruffians who ever afflicted a new country with their presence. The mere mention of his name terrified hundreds who had set at defiance the law and rulers of their own land. As the judge took his eat on that morning a stillness as of death fell upon the crowded room. Men seemed afraid to breathe, so great was the awe which the majestic presence inspired.

The judge charged the grand jury with words of flaming eloquence, in which he depicted the enormity of the offence with which the prisoner Robert Armitage was charged. A human life had been taken for the purpose of robbery, and the blood of an innocent man cried for vengeance upon his slayer. One of the culprits had met a merited fate, having lost his life while fleeing from the bloodhounds of the law. The other was in the hands of the officers of the Crown and against him an indictment had been framed, and would be laid before their body. It was their duty to consider the indictment, “and,” he added, with a menacing look that seemed to say, “throw out the bill at your peril,” “I leave the matter in your hands.”

The grand jurors were not long in returning a true bill for murder against the prisoner, and he was at once arraigned and pleaded guilty, no defence being possible. The prisoner, upon being arraigned for sentence, was the most unconcerned man in the room. He leaned against the side of the dock and yawned frequently while the judge addressed him in severe and unpitying language, telling him that no mercy would be shown him and that his execution upon the day fixed was as sure as the sun rose. When the man yawned for the third time the judge paused indignantly in the midst of a sentence and demanded to be told why he showed so much unconcern, under circumstances so dreadful that the entire courtroom was moved.

“Please, sir,” replied Armitage, “hurry. I ate no breakfast, and I want my luncheon. I am hungry.”

The man was then sentenced, without comment, to die on a certain date, and was removed from the dock.

A few days later Stephenson sought and obtained an interview with the doomed man. As he entered the cell unannounced, the prisoner, who was seated at a table, arose and, addressing his visitor, said:

“It is a long time since we met, Mr. Stephenson—at least since you were aware of my presence. I have seen you frequently, but you did not recognize me. When your cabin was robbed, I was there, and could have killed you, had I wished to do so, but you had been good to me, and I only gave you a light tap. We thought that your gold was between the mattresses, and we only intended to take one-half. But, as you know, we got nothing.” He paused, and yawned, as if he were bored, and wanted to shorten the interview.

Stephenson, who was disgusted at the man’s indifference, standing as he did, on the threshold of the other world, contented himself with handing him the letter from his wife.

Armitage opened and read it carefully, and without emotion, then crumpled it in his hand, and, turning to his visitor, said:

“”I owe you an aplology for treating you as I did, and for my indifference now. My wife writes me that you have been more than good to her. Continue to be her friend, for she is a good sort, and was never bad, although, to support me and furnish me with money to enable me to ‘buck’ at faro, she became a hurdy-gurdy girl. I always attended her to and from the hall, and, although appearances are against her, she is as pure as refined gold. Tell her that it is best that I should die, and that she will be well rid of me, in this world and the next. Tell her that when I am gone, perhaps her friends in the Old Country, who are rich and influential, will relent. All I ask is that my father and mother shall never hear of the way I died.

“My father turned me from his door because of something wrong that I had done, and bade me never to cross his path again. I married the sweet girl who calls me her husband under false pretenses. My name is neither Storm nor Armitage. I have been a sham ever since I can remember. I ought to have killed myself ten years ago, but I hadn’t the courage. I was starving when I assisted in waylaying those men and in sandbagging you. But that is no excuse for the crime I am about to die for.

“Gambling has been my curse and has brought about my ruin.

“Now, my friend, say that you forgive me for my treatment of you and say good-bye. I commit my poor wife to your care, and if I thought God would answer the prayer of such a wretch as I am, I would ask Him to bless you both. As it is, I can only hope that He will. I have told Mr. Elliott, the magistrate, everything—my name, and my father’s name. I have given him my signet-ring, and some other little things to forward to my father. Mr. Elliott will write that a horse threw me and broke my neck. He has pledged himself to keep my secret, and I know that he will keep that pledge. Good-bye, Mr. Stephenson—forever.”

Stephenson extended his hand, which the wretched criminal grasped, and pressed to his heart. It was the only time he had shown any emotion since the commission of the murder. Stephenson assured him of his full forgiveness and, promising to care for his wife, left him to his reflections. Upon the date set he was hanged, ascending the scaffold with firmness, declining to say anything. He died without a struggle.

Mr. Elliott, who subsequently became Premier, and whose grandsons, James A. And John Douglas, are residents of Victoria, lived for twenty-five years after the execution of Armitage, and the only thing he would ever say about him was that his family were among the highest in the kingdom, and dated their descent from William the Conqueror. I was once told that it was more than suspected that the criminal was closely related to a duke, but Mr. Elliott would never confirm nor deny that statement.

And what became of Mrs. Storm and her benefactor?

I wish I could reply that they were married and lived happily ever afterwards, as the story books say. All I do know is, that about five years after the tragic events which I have recorded, William Stephenson led a lady to the altar of Grace Church, in San Francisco, where they were made one. I never saw the marriage notice, but it is a strange coincidence that, in the next number of the San Francisco city directory the name of Mrs. Ella Storm did not appear, while that of William Stephenson did.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.