“The Fenians!” Was the Cry

Vancouver Island was in a state of emergency, 156 years ago.

While members of the Volunteer Rifle Corps and special constables patrolled Victoria streets, British men-of-war stood at the alert in Esquimalt Harbour and cruised Juan de Fuca Strait.

This is the little-known chapter of Vancouver Island's exciting history when it was feared to be the intended invasion target of the outlawed Irish nationalist society, the Fenian Brotherhood.

The Fenians were a real threat as shown here at the Battle of Ridgeway. —irishamericancivilwar.com

It had come to the attention of Lieutenant Governor Frederick Seymour and Rear Admiral George Fowler Hastings in February 1868 that the Fenians, who’d already attempted an invasion of Eastern Canada two years earlier, had decided to attack the colony of Vancouver Island, specifically Victoria. Extensive defensive measures were immediately ordered into effect.

Rear Admiral Hastings prepared for the worst. —Wikipedia

Civilians were pressed into service, the jails and armoury strengthened, armed guards stationed around city banks, and new breech-loading rifles issued to the reinforced San Juan Island garrison.

Colonial authorities had good cause for alarm.

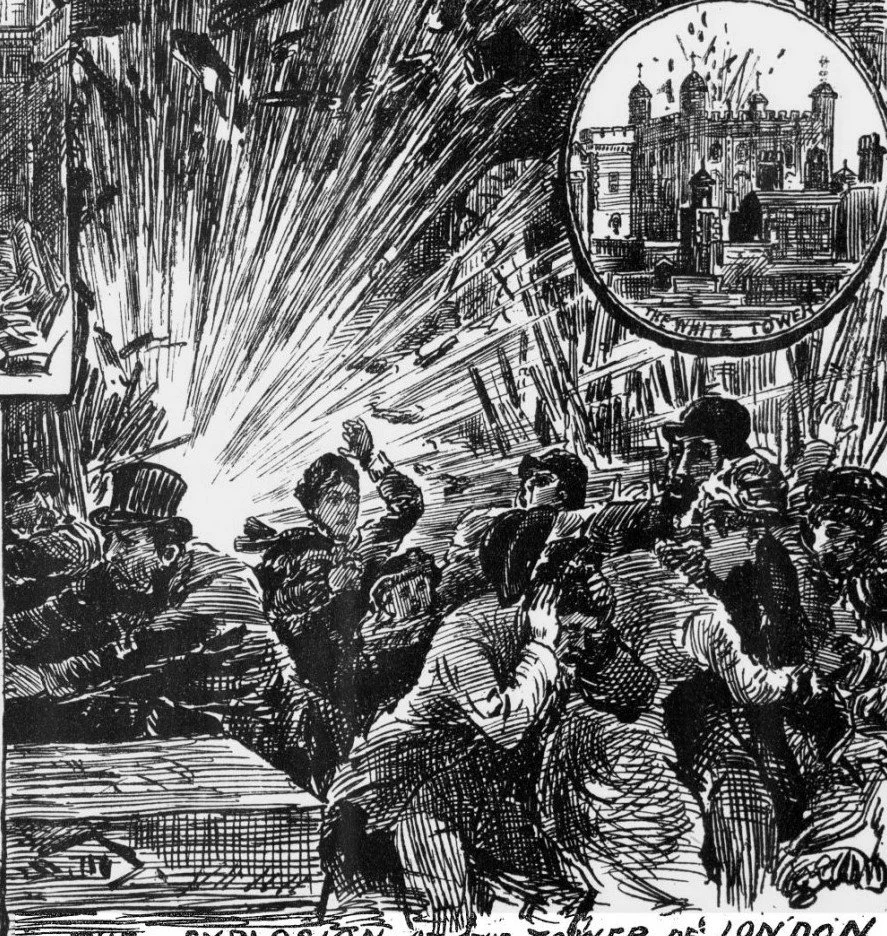

Every day, Colonist headlines reported Fenian outrages in England, as the Irish Independence movement picked up speed and strove to ignite a full-scale revolt. Bombings, murders, sabotage and raids on arms depots were a daily occurrence. The British Parliament met in emergency sessions to discuss the worsening situation.

Unrest in Ireland led to terrorist acts such as this bombing in London.—theirishhistory.com

What seemed to be a domestic British crisis began to assume horrendous international dimensions.

Britain was also deeply concerned with the war in Abyssinia. The U.S. was involved with the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. Tempers grew short. When Britain demanded that the U.S. help control the Fenians, “a festering sore” (many of the instigators in the United Kingdom were American citizens), Congress replied that it had troubles enough.

Not only that, but the U.S. was growing impatient for settlement of its Alabama claim. These were the reparations demanded by the American government for damages wreaked by English-built and English-manned Confederate commerce raiders during the recent Civil War. As these issues grew to a head, the threat of war between the two nations was seriously debated by both governments. The armed forces of both nations were placed on alert, the world waiting as a special American delegate hurriedly sailed for talks in London.

Although rumours had been sweeping Victoria for days, the Colonist first gave a full account of the suspected attack in an editorial on February 25th: "A number of absurd rumours were about yesterday concerning an anticipated Fenian raid, not one of which, we are happy to say, is correct. As we stated yesterday, every precaution has been taken by Admiral Hastings and the police authorities, in the face of which he must be a fool or mad man who would attempt an outrage.

“No doubt is entertained, however, by the authorities that a raid was contemplated by a band of men in California and that an emissary was sent among us to feel the ground.

“Finding, however, that his coming was heralded and that he was watched, he made himself ‘scarce,’ and he has not been seen since the sailing of the Eliza Anderson on Thursday morning last.

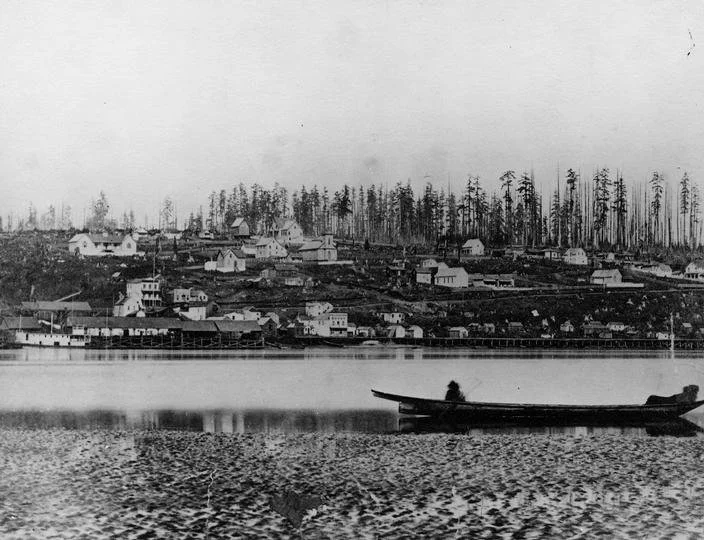

1860s Victoria at the time of the Fenian threat of invasion. —BC Archives

“This is the whole story. There was not the slightest foundation for the ridiculous rumours in circulation about town, and whatever danger there may have been a week ago, the admirable defensive measures taken have removed beyond the range of possibility the success of a hostile movement. But as in time of peace it is the ‘correct thing’ to prepare for war, too great energy cannot be displayed in adoption of measures calculated to deter lawless characters from even entertaining such an idea as the invasion of Vancouver island."

Other Colonist pages were crowded with reports of rioting in Britain and of trials for treason for leading Irish freedom fighters. With HMS Zealous continuing gunnery practice in the Strait, it was hoped that this display of strength would discourage the Fenians.

Although it had been reported that the Fenian "emissary” had departed from Victoria, authorities believed that he was still present. Admiral Hastings assured the public that "...We do not anticipate in the face of the precautions adopted any serious trouble at present." But as the threat continued to prey upon the minds of Victorians, the Colonist editor attempted to ease their fears with humour, reporting the “brave capture of a Finnian!”

“A veritable Finnian was captured in the outer harbour yesterday. It is supposed that he arrived off the Race Rocks during Sunday night, intending to run in under cover of the fog in the morning; but the fortunate appearance of the Zealous in Royal Roads, and the sound of her great guns, apparently confused him, and he attempted to escape towards the American side.

“His movements were observed, however by a patrol boat from the city, which had gone out early in the morning in search of just such characters. Chase was given, and after a pull of some miles the Finnian was captured after a stout resistance by the brave fellows in the boat, and conveyed to town, where he was ascertained to weigh 122 pounds. He was cut up into halibut stakes [sic] and retailed at one bit per pound by his captors."

In Britain, the Fenians were looked upon with little amusement, as MP Earl of Mayo, Chief Secretary for Ireland, asked that Parliament suspend the writ of habeas corpus (in effect establishing martial law).

The Earl of Mayo urged Parliament to impose martial law in Ireland. He was assassinated four years later. —Wikipedia

He maintained that “although the government has succeeded in suppressing the rebels, still an extension of its powers is necessary to enable it to complete its work." The bill was passed and additional troops were rushed to strife-torn Dublin. The Colonist reported that the Fenian organization in the U.S. had been placed on a “war footing," indicating that an actual invasion of Canada was indeed contemplated.

At 4:00 on the morning of March 6th, the cry, “The Fenians! " swept Victoria.

A special constable patrolling Government Street had turned in the alarm that Cleal’s restaurant was burning. It was Fenian practice to set a fire to create a diversion then strike the banks. Admiral Hastings, immediately informed, took no chances. As Fire Chief Kelly and his men of the Tiger Fire Company rushed to the scene, a detachment of 50 Royal Marines was put ashore from Her Majesty’s Gunboat Forward.

Emergency police officers also answered the call. While the firemen fought to control the rapidly spreading flames, the marines and constables took up positions around the town's banks.

The inferno, fanned by a harbour breeze, spread to surrounding buildings. A young firefighter named Joseph Davies, while supporting a hose, slipped from the roof of the restaurant and fell into the middle of the flames, but remarkably escaped with only slight cuts and bruises. A few hours later, the blaze was under control and Chief Kelly inspected the smouldering ruins. His suspicion of arson confirmed, this information was rushed to authorities.

The marines and police waited apprehensively but dawn came without a sign of a Fenian attack.

As it became apparent that it had been a false alarm, the city breathed a sigh of relief. Subsequent investigation resulted in the arrest and committing for trial of the restaurant’s owner. He’d apparently lost the same business under similar similar circumstances two years before. The charge was eventually dismissed for lack of evidence.

The following day, a “practical joker” wrote to the Colonist warning of a plot to disable the town's fire engine, cut the alarm ropes and set fire to the city. Although most recognized it as being from a crank, others, their nerves already strained, grew increasingly apprehensive...

As days passed without appearance of the invaders, the Colonist and the British Columbian of New Westminster engaged in a public argument as to which city was the most more desirable target!

New Westminster, as it looked in 1863, five years before the Fenian threat. The Royal City wasn’t worth invaders’ bother, according to the Colonist. —BC Archives

The Colonist editor pointed out that New Westminster was unlikely to be raided as it was a town “whose poverty is so notorious as to hold out every inducement to plunderers to give it a wide berth quote”. He reminded Victorians that “every precaution has been taken, every assistance rendered by the Fleet, and every probable point of attack is at least well guarded from assault; but it will require the presence of all Her Majesty's vessels now on this station to lie within easy call of Victoria and Esquimalt for some time to come to overawe any evil-disposed persons who may cast longing eyes upon our wealth, and who may hope by a sudden raid to strip the banks of their gold.

“New Westminster, as we have already remarked, finds her greatest protection in her poverty.

“She possesses nothing worth stealing, and the general who would attempt to march a force so far into the interior of the colony before he had first secured the point of supply and the single ‘key’ to the position [Victoria] lying directly in his path and from which he could be harassed by a ‘fire in the rear,’ would be a greater dolt than the alarmed genius at the capital who has suggested that the Fenians will quietly gobble up our ‘worthy Governor’ and hold him as a hostage while dictating terms for the ‘liberation of Ireland’!

The Government by remaining at New Westminster is safe—too safe for the interests of this section of the colony. Its duty calls it here. An undue concern for his own importance and value (which is not shared by any of its subjects) impels it to remain remote from the only probable scene of action in case of an invasion.

Her Majesty’s Gunboat Grappler was dispatched to guard Burrard Inlet’s valuable sawmills and shipping. —SB Heritage & Archives

“At Burrard Inlet, where much valuable mill property is at state, the presence of a gunboat would, perhaps, be advisable for a short time; but the proposition to send a ship of war to New Westminster, where there is virtually nothing to protect, is so monstrously absurd as to admit of no feeling but one of pity for the imbecility of the writer who has given it utterance."

Newspapers had much freer editorial rein in those days! It must be remembered that Victoria and New Westminster were vying for the honour of being named capital of the newly combined colony of British Columbia and Vancouver Island.

On March 14th, Her Majesty’s Gunboat Grappler took up position to guard New Westminster and Burrard Inlet. March ended with Admiral Hastings holding a review of Her Majesty's forces in Beacon Hill Park and the Ordering of HMS Forward to conduct firing practice in the Strait.

* * * * *

Modelled on the French revolutionary Jacobins and named after a legendary band of warriors called ‘Fianns’ or ‘Feinnes,’ the Fenian Brotherhood was established in the U.S. in 1858. Its fanatical members swore an oath allegiance to the Irish republic, now virtually established," and swore to rise in arms when called upon. They also agreed to yield total obedience to their officers.

—Wikipedia

Although Fenian chapters soon existed in many countries, the group never gained popularity with the Irish majority, the agricultural labourers.

But during its brief career the society kept much of the world's attention focused on Ireland, as it created one furore after another. With the end of the Civil War, thousands of Irishmen who’d served swell its ranks, making it a formidable organization.

The same year, 1865, the party split over the question of invading Canada. The fanatics demanded that Canada be conquered and “used as a base of operations against Britain”. The official—and logical—view was that such action would do little, if anything, to aid Irish independence. But when Britain quelled the abortive uprising in the Emerald Isle, plans to invade Canada were set in motion.

Canadians grew apprehensive as it was reported that 1000s of armed men were beginning to gather along her southeastern border.

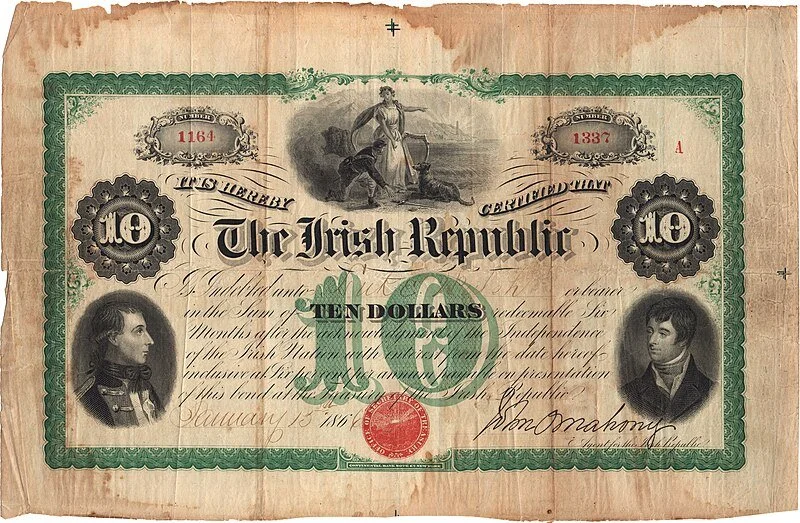

Through the sale of $10 bonds such as this one, the Fenian Brotherhood raised 100s of 1000s of dollars with which to buy arms intended for use in invading Canada. —Wikipedia

It was the Fenian design to enter Canada with three forces, one striking at Fort Erie, another attacking Prescott in a salient aimed towards Ottawa, and the third slashing northward through the Eastern Townships. In March 1866, the Canadian government asked for 10,000 volunteers. 14,000 answered the call.

The following month, a small band of raiders was discouraged from attacking Campobello Island in Passamaquoddy Bay by U.S. authorities and the presence of British warships in the vicinity. Although no major invasion occurred in 1866, two minor attempts were made. On June 2nd, ‘Inspector General’ John O'Neill, a calvalry officer in the Civil War, led 800 men cross the Niagara River into Canada near Fort Erie and camped at Ridgeway.

Fenian firebrand John O’Neill. —irishamericancivilwar,com

However, many of his followers soon began to desert him. He was immediately attacked by a slightly larger Canadian force but confusion in the Canadian commands cost them an easy victory. As strong volunteer reinforcements advanced, O'Neill ordered retreat.

A detachment of 80 volunteers delayed his withdrawal in a gallant but vain attack. The Canadians lost two men and incurred 40 wounded. Fenian casualties were thought to be twice as many. The remnants of the invaders surrendered to the U.S. warship Michigan on June 3rd.

The following day, a Fenian army 1800-strong marched from Vermont into Missisquoi County in the Eastern Townships. Camping at Pigeon Hill, roving bands of drunken raiders plundered the towns of Frelighsburg and Saint Armand. However, they retreated into the U.S. a few days later.

The next threat came two years later when it was feared that Vancouver Island would be the battleground. But an attack never materialized. The strength of the Pacific Squadron of the Royal Navy undoubtedly discouraged any such plans.

But Canada was kept in a constant state of tension although the U.S. and Britain resolve their difficulties and remained at peace. (An international tribunal settled the Alabama claims in 1872, awarding the U.S 15. $15.5 million in damages.) In 1870, O'neill, then president of the Fenians, again struck the Eastern townships. But after coming under fire at Eccles Hill on May 25th, he withdrew. U.S. authorities, finally tired of the business, arrested him. The following day, the last raiders were routed and a brief skirmish at Huntington in October 1871, without sanction of the Fenian Brotherhood, O'Neill seized the undefended Hudson’s Bay post, Fort Pembina, about three miles north of the Manitoba-U.S. border.

Four hours later, U.S. troops intervened, arresting O'Neill and his supporters. This is probably the only occasion in Canadian history when American cavalry arrested an army on her on her soil!

However, although the raiders were soon released on a technicality, the Fenian movement was dying and Canada was never again attacked. Condemned for its clandestine activities by the powerful Irish Catholic church, with most of his leaders in prison, and with the American government finally clamping down on his militant actions, it was disbanded.

Ironically, in the long run the Fenian raids proved beneficial to Canada. Military appropriations were increased and the militia reorganized into an efficient force.