The Ghosts of Royston Are Still With Us

One of my true regrets of having earned my journalistic spurs back in the ‘60s is that newspapers and magazines at the time were mostly black and white.

Meaning no, or rarely, colour photos because they were too expensive to process and to print.

Meaning that I took 1000s of photos in black and white—and we now live in an age of full colour reproduction! For example...

The hulk that most intrigued visitors in the ‘70s was that of the Aberdeen, Wash. sailing ship Forest Friend, built in 1919. —Author’s Collection.

This sad reality of technological change came home with a pang with my intention to revisit the historic shipwrecks of the Royston Breakwater. How many times I toured those ghostly ladies of the sea when, with permission of breakwater owner, Crown Zellerbach, I was allowed to clamber over, in and around them to my heart’s content, shooting photos—black and white photos, alas—all the while.

Think of it—the current owner’s insurance company would probably have a fit. But all that was required then, courtesy of CZ, was that I check in with their watchman on the rare occasions that he was on duty.

Besides my camera I carried a small tool kit—to rescue bits and pieces that weren’t too rusted or otherwise corroded to come free with a little effort. I didn’t even need a wrench or a crowbar to access a flag locker on the Second World War navy tug Sea King to retrieve port and starboard lamp lenses and some brass fittings which had been left when she was scrapped in Victoria.

But instead of being cut up she (her hull, anyway) and her sisters—other tugs, sailing ships including one of the famous clippers, destroyers, and frigates—were placed on duty at Royston to protect the log booms from storms.

Somewhat to my amazement, they’re still there although no longer on duty and in a much reduced way since my visits of long ago. So let’s begin with a replay of an article I wrote (the first of what became a series) for the weekend Islander magazine of The Daily Colonist way back in 1971.

* * * * *

For those who visit Crown Zellerbach’s graveyard of ships at the Royston booming grounds on the western shore of Comox Harbour it’s an intriguing experience, almost like stepping backward in time. If they listen carefully they may hear more than the lapping of waves alongside and the cooing of pigeons from within darkened passageways.

Those whose imaginations are so attuned may hear whispered tales of a golden past when these sheltered hulks were more than skeletons of rusted, twisted steel and wood.

For these once-upon-a-time seagoing ladies can speak of the glories of sail, of shipwrecks, mutiny and murder on the high seas, of war in the North Atlantic and in the Far Pacific.

This is what the death watch at Royston is really about for those visitors who love and know their marine history.

Originally these booming grounds where logs were rafted for the long haul to mills by tugboats, were protected only by a system of boom chains. When this proved to be an inadequate defence against the southeasters that roared in from the Strait of Georgia, the first hulks were anchored as a makeshift breakwater in the 1940s.

Of the many ships—from lowly tugs to sleek clipper ship to Second World War frigates—which have stood watch here over the years, several have vanished beneath the mudflats and latter-day rock-fill. Now only the ravaged remnants of 14 ships (as of 1971) remain visible, a rusty capstan or a still-sheer bow recalling a forgotten age.

Launched at Port Glasgow for the Anglo-American Oil Co. of London in 1920, the 323-foot, 2874-ton Comet was one of the largest barques ever built. By the 1920s, long after the advent of steam and even diesel, the steel four-master had known several names and several roles. As the Orotava, she joined Capt. Robert Dollar’s famous fleet of sail as the James Dollar, sailing for Yokohama with lumber form Bellingham early in 1927. Upon returning in ballast, she was laid up on Lake Union until sold to Pacific (Coyle) Navigation Co., Vancouver. With sister ship William Dollar, she was cut down to a barge, becoming Pacific Forester.

By 1936 she was owned by Island Tug Barge Ltd., Victoria, as the Island Forester. Eleven years later she was converted to “one of the most modern log-carriers on the Pacific Coast,” boasting of three derricks capable of loading a million board feet of logs in 48 hours. Until purchased by Crown Zellerbach, to become CZ No. 2, the rejuvenated barge served between the Albernis and Port Angeles. Finally she joined the Royston breakwater.

By 1971 only her bow remained. A few hundred feet from her nearest neighbour, the severed section section sat perfectly upright and alone, identified only by her insignia, CZ No. 2.

CZ No. 3 was another veteran of the Dollar fleet. Also built in Port Glasgow, in 1894, the 2200-ton sailing ship was originally the Riversdale. Sold in 1910 to German interests, and renamed Harvestehude, she was forced to spend much of the First World War at anchor at San Rosalia, Mexico, trapped by British warships. Three years after Armistice, Capt. Dollar took her in hand.

His plans for her, however, weren’t realized and she endured a further two years of enforced idleness at San Francisco until bought and reduced to a barge by James Griffiths & Sons, again bearing her maiden name of Riversdale.

Several months before I first wrote about the Royston breakwater for the Colonist, 14 tons of fittings from the Riversdale were shipped to the San Francisco Maritime Museum after being stripped from her hulk at Royston. Her equipment was intended for use in the full-rigger Wavertree which had been working as a sand barge when it was rescued for restoration. She and the Riversdale were the last survivors of a large fleet owned by Leyland Brothers of Liverpool.

Towed to New York by tug, the Wavertree restoration was expected to cost a million dollars and take four years to complete.

New Yorkers can book events aboard the restored 1885 Wavertree, owned by the South Street Seaside Museum, whose website says, “This historic ship provides a breathtaking setting with unparalleled views of the Brooklyn Bridge and Manhattan skyline.” Thanks, in part, to the salvaged artifacts from the good ship Riversdale. —South Street Seaside Museum website.

Still showing the stump of her bowsprit, what’s left of the Riversdale.—Nauticapedia

For years, a local link with the all but forgotten Riversdale forgotten was a brightly painted young lady in riding habit who graced the entrance to the landlocked restaurant ship, Princess Mary, on Harbour Road. For 16 years the battered figurehead had been overlooked in storage until Island Tug & Barge president Harold Elworthy had it restored and mounted. Thereafter, until the Mary’s demolition for development, she stared, sightless, skyward, a rose in her hand, while perhaps reminiscing about a glorious youth when she’d tasted salt spray, fog and hail, from Firth of Clyde to Cape Horn to Juan de Fuca Strait, on the bow of the good ship Riversdale...

For years, Riversdale’s restored figurehead was mounted outside the famous Princess Mary Restaurant. —Author’s collection.

A third wreck known to be at Royston (I was to later learn that Crown Zellerbach’s records of the ships in its breakwater were incomplete) was that of the First World War auxiliary schooner Laurel Whalen. Her hulk appeared to have sunk into the mud by 1971 as there was little to be seen of her. In 1965 Princeton resident Art Shepton recalled, in the Vancouver Sun, having seen the Whalen in Auckland Harbour in 1919. At that time, he said, her engine had broken down and he crew were demanding passage home to B.C.

“I left New Zealand and a year later — met an AB that was on the Laura [sic[ Whalen. He said that after she was repaired she sailed for Vancouver and ran into heavy seas and the rigging was torn away. The skipper went to the sick bay with a broken leg. The ship was disabled and they put into Tahiti where she was beached. Then she was allowed to proceed under ballast and tow.

“The old tugboat Lorne of Vancouver went south and towed her to Vancouver via Hawaii. At that time I think it was the longest tow ever attempted.”

Upon returning to her home port after the tumultuous voyage that had lasted two years, the weary schooner was reduced to a barge and eventual assignment to Royston.

The hulk which most intrigued visitors in the ‘70s was that of the Aberdeen, Wash. sailing ship Forest Friend. Built in 1919, the 1500-tonner’s ravaged carcass offered an intriguing glimpse into the almost forgotten art of mass-produced wooden ship building. Her gaunt ribs and exposed sides revealed thousands of wooden dowels and hand-forged iron bolts. Such ships were built to withstand the elements and, 50 years after she slipped down her builders’ ways, Forest Friend was still on watch at Royston.

Two views of the Forest Friend, from deck level and from her pilothouse (below). —Author’s Collection

The Forest Friend’s stout construction had withstood more than savage gales on the high seas—she’d even defied the force of a bulldozer when workmen filling the breakwater with rock had attempted to collapse her port bulwarks. Instead, they had to make the breakwater take a slight turn to starboard—because when the bulldozer had released its pressure, her sturdy timbers had snapped back into place with little more than a bruising!

Visitors who braved her gaping decks could enjoy the view from her pilothouse, an obvious add-on from her time as a bulk log carrier; deeper within they could yet see the “certified cabins” from her days as a proud ship of sail. (I have as a souvenir, one of her two-inch-thick deck lights which, when cleaned of its coating of tar, shows as a beautiful pale purple from its long exposure to the sun.)

The CPR tug Nanoose whose steam engine is still all but intact after all her years above and below the sea at Royston.—Author’s Collection

Perhaps the humblest members of the Royston breakwater were the former CPR tugs Nanoose and Qualicum, 40-year veterans of B.C. coastal waters. A further two decades of wind and wave at Royston hadn’t been kind to these staunch little workhorses and, by 1971, Capt. John Troup wouldn’t have recognized poor Nanoose, his creation of so long ago.

“This morning at Esquimalt the new tug Nanoose,” reported the Victoria Daily Times in May 1908, “built according to the design of Capt. J.W. Troup, superintendent of the CPR coast service, was launched at the yard of the B.C. Marine Railway Company.

“The launch was a complete success, but owing to the early hour, the state of the tide necessitating the floating of the vessel before 5 o’clock, few were present beyond the workmen. All the machinery for the tug had been made at the local shipbuilding company’s yard and will be fitted without delay, as the tug is required by the CPR for use during the summer, towing the big new barge car ferry built by the Victoria Machinery Depot at a cost of $25,000, between Nanoose ferry depot and Vancouver.

“Built according to the plans and specifications of Capt. Troup, the new steel tug is one of the most up-to-date and powerful vessels of her size on the north Pacific coast. She is 90 feet long and has a big sheer and long bow.”

Actually, 305-ton Nanoose’s overall length was 120 feet, and she was capable of 12 1/2 knots. Qualicum was only 200 tons, 112 feet long, and could attain 10 knots. Built as the Colima by the Philadelphia firm of Neafie & Levy in 1904, Qualicum saw service in the construction of the Panama Canal, according to her official CPR record.

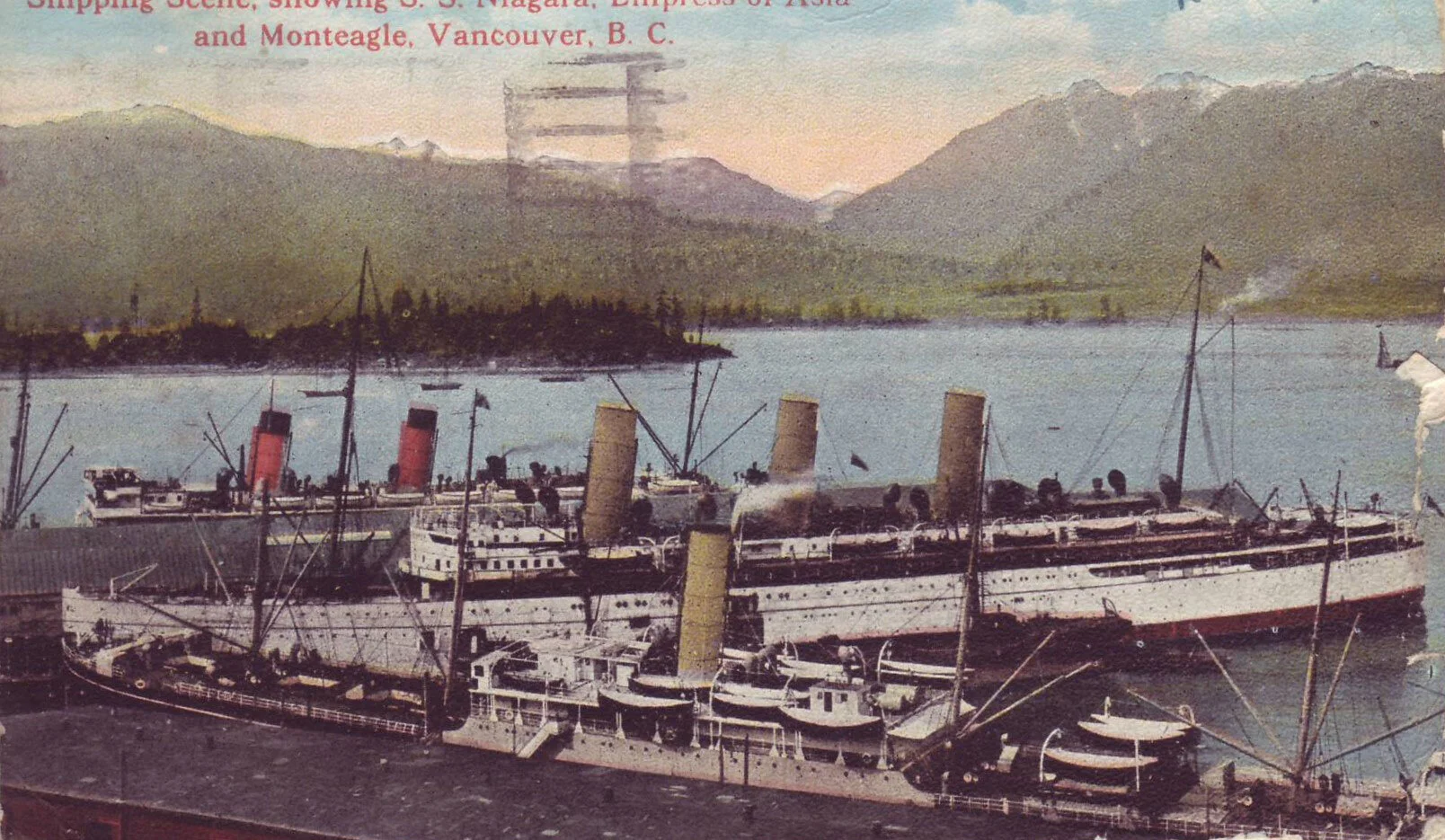

One of the famous Empress ships, mid-photo. For years the tugs Nanoose and Qualicum shepherded the former clipper ship Melanope which had been cut down for service as a fuel barge. All three historic vessels are in the Royston breakwater. —Author’s Collection

Best remembered for their roles as shepherds to the company’s sailing barge Melanope as she fuelled the famous white Empresses and Princesses, neither tug had experienced more than hard work during their busy careers although at least two incidents provided the little drudges some interesting moments. Such as the time the historic coastal steamer Tees grounded in Haro Strait in 1918. On her maiden run as replacement to the disabled steamship Otter in the Gulf Islands service, Tees had struck heavily and filled on Zero Rock. Passengers and mail were evacuated by the steamship Coaster as Qualicum and the steamer Alaskan sped to assist from Vancouver.

Tees was ripped from bow to amidships, but crews of the salvage vessels, through the use of powerful pumps and a blanket patch, managed to re-float the liner despite her continuing to list 20 degrees to port. Then, Alaskan alongside and pumps steadily draining her flooded holds, Tees limped into Victoria at the end of the Qualicum’s towline.

Six months later, both Qualicum and Nanoose participated in the salvage of another company ship, the Princess Adelaide. Reported the Colonist: “Blinded by a dense blanket of fog, lured on by deceptive fog horn blasts and carried out of her course by treacherous currents, the CPR steamer Princess Adelaide, Capt. Hunter, crashed on the shoals of Georgina Point, the northern spur of Mayne Island at the entrance to Active Pass, Sunday noon.

“The vessel is said to be seriously damaged, several plates being stoved [sic] in, and all her oil tanks punctured. She is still firmly wedged on the rocks. All of her 360 passengers were transferred without panic or mishap to the CPR steamship Princess Alice a few hours after the accident and brought to Victoria Sunday night. The stranded vessel was bound from Vancouver to Victoria.”

Three hours later, Nanoose and the steamship Tees, now a member of the B.C. Salvage Co. fleet, secured hawsers aboard the Adelaide and heaved at full steam. But a falling tide defeated their efforts; Adelaide remained hard aground.

Five days passed with the Princess still held fast on her rocky perch. Aided by Qualicum and the tug Dola, Tees and Nanoose again tried hauling the stranded liner free, but to no avail. The following day a northwesterly wind caused the ship to grind heavily on the reef while the tugboat crews unloaded everything they could that was portable to lighten her.

October 17th, at high tide, the rescue ships, reinforced by the tugs Tatoosh and Nitinat, made another herculean attempt. Straining mightily, they felt Princess Adelaide move slightly. One foot. Two. Ever so slightly, she began to ease seaward. Suddenly, Nanoose’s towline snapped, snaked through the air and fell limply into the water. They’d failed again.

Finally, on the afternoon of the 28th, on the highest tide of the month, Adelaide slid, groaning, into deep water. Hours later, the tugs triumphantly hauled the crippled liner into Victoria.

After the Second World War, doughty little Qualicum and Nanoose, stripped of everything salvageable, were towed to Royston, there to join their old charge, Melanope, in watching over the booming grounds.

Once the clipper ship Melanope, launched in 1875 and said to have been cursed and dogged by misfortune that included suicide and murder from her maiden voyage on, had been acclaimed for her beauty and her speed, an amazing 13 knots.

But the hull of the Melanope of the Royston breakwater when I first set eyes on her was already broken in three and mostly reduced by storms to her mid-section.

Another ill-fated lady to end her days in the Crown Zellerbach death watch was the deep-sea tug Salvage King whose career as a wartime naval tug and fire boat ended, ironically, in a devastating fire.

So I wrote so many years ago. As a result of that article in the Colonist Crown Zellerbach commissioned me to write a series in the company newsletter. This required that I do more research into the ships in their breakwater; as a result, and with the help of company files, I learned more about them and my file has continued to grow over the years.

An eerie view through a port hole... —Author’s Collection

The former booming ground breakwater is still there although it’s broken into pieces by more decades of storms so you can no longer walk its length and climb aboard many of the historic ships that formed its original vertebrae.

Courtesy of the Underwater Archaeological Society, these are the ships that ended their seagoing careers in the Royston breakwater: Blue (or Black), Comet, HMCS Dunver, HMCS Eastview, Forest Friend, HMCS Gatineau, Laurel Whalen, Melanope, Nanoose, HMCS Prince Rupert, Qualicum, Riversdale, Salvage King, USS Tattnall. It’s a motley inventory: three frigates, two destroyers, one whaler, two three-masted Cape Horn windjammers, two lumber carriers, a case oil freighter, and three steam tugs.

In 2011 the UASBC undertook an above and below the water reconnaissance survey of what’s left and accessible of the breakwater and concluded that Royston’s ‘breakwater fleet’ is “one of the premier ship graveyards on the West Coast of North America, and a valuable site for future maritime archaeology projects. Its collection of historic sailing, steam-era, World War One and World War Two vessels spans the transition from sail to diesel turbine power and two of the major conflicts of the 20th century.”

The USABC recommended that the site “be left intact and the protection afforded archaeological sites under the Amended Heritage Conservation Act, be continued for the wrecks, pilings in the immediate vicinity, and the associated rock breakwater”.

The stories these ships of this iconic ghost fleet can tell: of wooden ships and iron men, of storms and shipwrecks, of jinxes and heroism and of both world wars...

We shall return to the Royston breakwater from time to time in future Chronicles.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.