The Golden Age of B.C. Shipbuilding

Everyone has seen the story in the news: B.C. Ferries has contracted to spend billions—billions—of dollars, building new ferries in China.

The only surprise is China; we’ve been buying ferries from European countries for years.

Shift change at Burrard Shipyards, 1944. —BC Archives

There was a time, not really all that long ago, when shipbuilding in B.C. was a mega industry, one absolutely vital to the nation’s defence and to its economy. We still have shipbuilding, of course, but nothing like in the old days; the fabled shipyards of Vancouver and Victoria are history.

And since history is what the Chronicles are all about, let’s look back in time to when this marine industry, like charity, began at home.

* * * * *

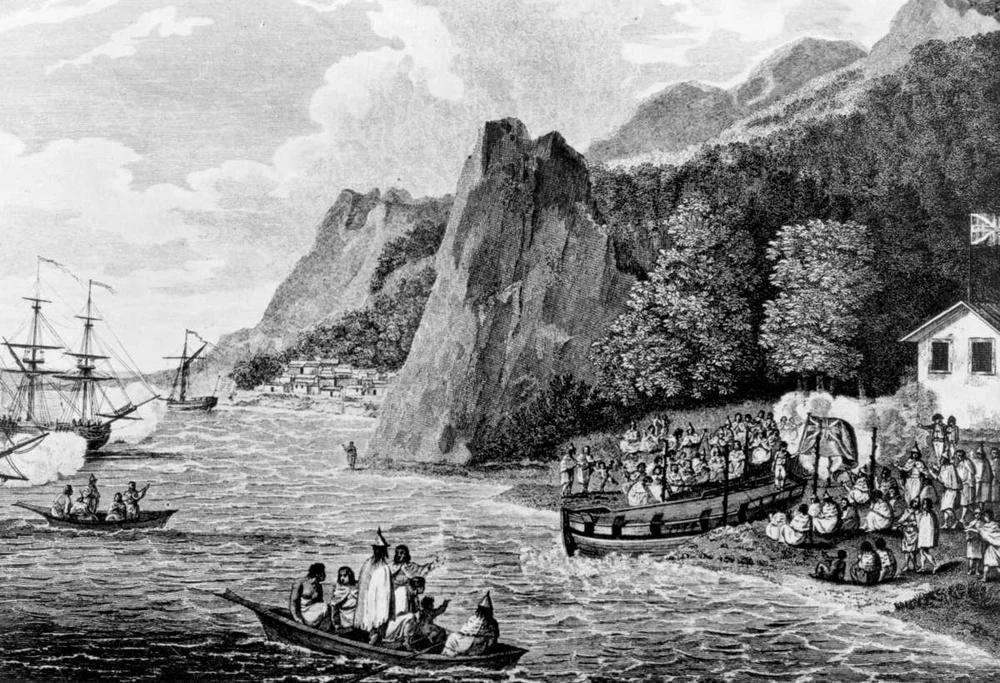

B.C.’s first shipbuilder was Capt. John Meares who launched the sloop North West America at Friendly Cove, V.I., in September 1788. It was “the first non-Indigenous vessel built in the Pacific Northwest”.—BC Archives

To put today’s Chronicle in historical context, rather than in chronological order, let’s begin in the summer of 1958 when ferry connections between the Island and Lower Mainland were provided by two private companies, CP Steamships and the American-owned Black Ball Line.

The famous Canadian Pacific Princess ships had long filled this role, to the point of having become an institution, but when its employees and those of the Black Ball Line struck together that summer, strangling crucial Island-Mainland ferry service, Premier W.A.C. Bennett responded boldly.

He created BC Ferries as a Crown corporation with Highways Minister Phil Gaglardi at the helm.

A fully-functional ferry service between Swartz Bay, Sidney, and the newly-built terminal at Tsawwassen wasn’t accomplished overnight, of course. But, within two years, BC Ferries had its first two purpose-built ships, the MV Tswassen and the MV Sidney on the job—the beginning of its own fleet. Other vessels—also built locally—followed over the next five years as the young corporation expanded to provide vehicle ferry service to other small coastal communities.

Built locally? Yes, B.C. had several thriving shipyards in Vancouver and Victoria to draw upon: Burrard Shipyard, Yarrows and the Victoria Machinery Depot, to name the three leading contenders of the day, all of whom had decades of proven performance behind them.

Now we’ll get down to, more or less, chronological order; readers are advised that today’s Chronicle is a thumbnail sketch of the province’s shipbuilding heritage—a detailed account would take volumes. That said, let’s begin at the beginning (Capt. Meares aside), with Capt. Joseph Spratt’s Albion Iron Works in Victoria.

Workers and staff of the Albion Iron Works pose for the photographer in 1897. This company was better known for its stoves than for its shipbuilding. —BC Archives

At one time this iron works, founded in 1863, was the largest of its kind north of San Francisco, with 230 employees, and occupied a 1.5-hectare waterfront property in the Inner Harbour. Among its many products were machinery, railway cars, steam engines, boilers, water pipes, stoves and, an oddity of that day and age, cast-iron storefronts. There were changes of owners and direction over the years, then, while managed by Spratt’s son, Charles, a merger with Victoria Machinery Depot, whose name it assumed in 1888.

Over those decades, VMD survived two devastating fires and expanded and contracted in response to economic demand and according to national need.

During its first 30 years this yard produced 13 modest vessels, including four sternwheel riverboats, three minefield tenders, three tugs, two barges and a small passenger/cargo ship, the S.S. Joan.

Shipbuilding then slowed to a crawl, only two ships and two barges. But that changed dramatically come the Second World War: no fewer than 26 ships, from five naval corvettes to 14 cargo ships, five tankers and a stores ship. To facilitate this building binge, the company had to buy the Rithet piers at the Outer Wharf, and 17 adjoining acres, in 1941.

That was when Canadian women joined the national workforce by the 1000s in place of so many young men away in uniform—the time of, below the border, the legendary Rosie the Riveter.

Wartime workers at VMD line up to buy war bonds in 1943. —BC Archives

Also filling in were older men, among them my maternal grandfather, John Thomas Green, and Uncle Adam; I have a photo of them, among the rows of middle aged and older men in overalls, posing for posterity at VMD.

Another Second wartime freighter is launched at VMD, this one in 1944. —BC Archives

After war’s end through 1957, the Victoria yard hardly missed a beat: 20 freighters including the famous government-owned Park ships, several barges and their first ferry, this one for the Department of Public Works, three more minesweepers, a tug, barges and two of Canada’s post Second World War “Cadillac” destroyers, HMCS Terra Nova in 1955, and HMCS Saskatchewan, in 1963.

VMD even got into building mini submarines such as the famous Pisces, all while producing specialty equipment for manufacturing purposes.

This was the golden era of the new and growing B.C. Ferries Corporation: no fewer than 14 ferries, beginning with the MV Sidney, later renamed Queen of Sidney. She, and other Queens required maintenance, repairs and retrofits such as being cut in half and lengthened. There was also extensive refit and conversion work for the navy.

Its most singular project, in 1965-67, was the Sedco 135-F, the first oil drilling platform constructed in B.C. and, at that time, the largest semi-submersible platform in the world. (I can remember viewing it from the top of Mount Douglas/Pkols; with Juan de Fuca Strait and the Olympics as a backdrop, it dominated the Victoria waterfront—it was huge.—TW)

The ungainly looking Sedco 135F oil platform take shape at VMD. —www.pinterest.com

But, when the glut of new ferries ended and the Sedco-135F was completed, business slowed and, with no new shipbuilding contracts in sight, the company sold its Outer Wharf holdings and turned to manufacturing specialty equipment for the oil and gas industries.

By 1985, after two changes of ownership, it was in receivership and bought by 23 of its employees; in 1994, after 131 glorious years, Victoria Machinery Depot that a newspaper described as Victoria’s “oldest factory,” closed its doors.

Victoria’s other venerated shipyard was Yarrows Ltd., originally the Esquimalt Marine Railway Co., 1893-1987. Ironically, it was founded by William Fitzherbert Bullen, an Albion Iron Works executive, because he couldn’t convince its management to build a marine railway. Acquired by the famous British shipbuilders, Yarrows, in 1913, it later became amalgamated with Burrard Dry Dock as Burrard Yarrows Corp., then became Versatile Pacific Victoria upon acquisition by the Versatile Corp. in 1979.

Between 1896 and 1938, Yarrows built 26 vessels besides a yawl, several wooden caissons, barges, two dry dock gates and a minesweeper, the latter a foretaste of the shipbuilding binge that would be prompted by the Second World War: 28 frigates, 10 landing craft and five corvettes.

Not to mention Canadian National Railway’s last coastal passenger liner, S.S. Prince George, an RCMP patrol boat, a Canadian Coast Guard patrol vessel, an icebreaker, two research vessels, a survey vessel, a fisheries patrol vessel, an offshore supply ship, a pile driver, a buoy tender, two small ferries, a fire boat, tugs, barges and scows. Not to mention shell casings and repair work and employing, during the First World War, as many as 800 workers.

Two partial ferries, the 1990s Spirit of Vancouver Island and Spirit of British Columbia were built by Versatile Pacific as sterns only.

The company closed in 1987 and its former facilities now part of CFB Esquimalt, our westernmost naval base.

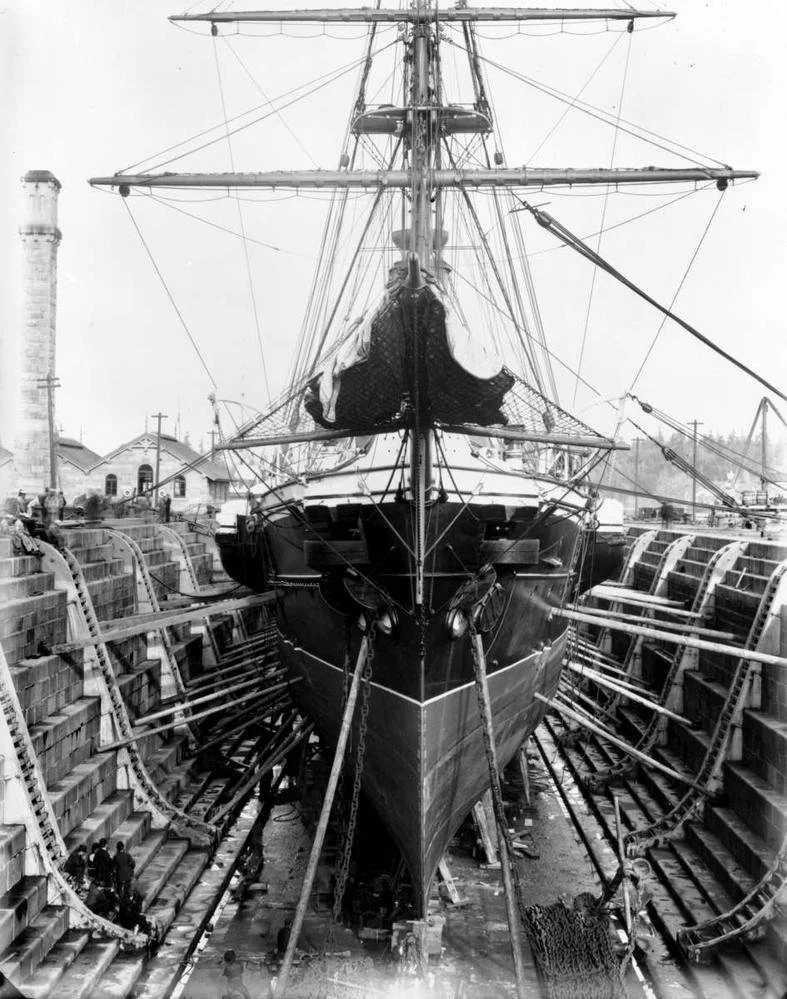

It was colonial Governor (Sir) James Douglas who suggested to R/Admiral Henry Bruce, RN, Commander-in-Chief Pacific Station, “I think you would find it convenient to make this place, Esquimalt, a general naval depot for the Pacific Fleet.” At that time the Royal Navy’s only other dry dock was in distant Valparaiso; when serious repairs were needed by the fleet, ships had to go to Seattle.

As a bargaining chip in negotiations for Confederation in 1871, Esquimalt was promised a dry dock. Work was begun in 1876 and commissioned in 1887. From the start, business was brisk for the naval graving dock: 70 naval vessels and 24 merchantmen. Through 1927 the dock averaged 21 ships annually then suspended service until 1945.

Two views of the naval graving dock showing HMS Amphion in 1889 and a much more modern destroyer, HMCS Mackenzie in the 1960s. —BC Archives

But ships, naval and merchant, kept getting bigger; so in 1924 the Canadian government built the nearby and larger Esquimalt Dry Dock, able to accommodate ships that plied the Panama Canal.

The size of a propeller of RMS Empress of Japan shows dramatically in this photo taken when the passenger liner was in the Esquimalt graving dock in 1935. —BC Archives

Over the past century its largest, most renowned “guest” was the RMS Queen Elizabeth, in 1942. The Graving Dock,“the largest non-military hard bottom dry dock on the west coast of the Americas,” has since been renovated to accept cruise ships with their extended stabilizers.

* * * * *

Before leaving Victoria, it should be noted that, during the First World War, Victoria Machinery Depot and Yarrows Ltd. weren’t the only significant shipbuilding firms. There was also Cameron Genoa Mills Shipbuilders, a seemingly unlikely venture by the Cameron Lumber and Genoa Bay Lumber Co. to cut out the middleman, so to speak, by building four wooden merchant ships, schooners all, in their Inner Harbour yard for the government.

In 1917, the East Coast’s Foundation Co. also chose the Inner Harbour for its Pacific shipyard; its Point Hope site, used by various firms for this purpose since 1873, continues to build and repair vessels to this day, latterly as Seaspan’s Point Hope Marine. Foundation’s Great War contribution was another 25 wooden cargo ships.

Besides these yards there was Victoria Machinery Depot’s Great War subsidiary, the Harbour Marine Co.

Launching of the SS War Yukon at the Foundation at the Foundation Co.’s Victoria shipyard in 191-. —BC Archives

* * * * *

Which brings us to the greatest B.C. shipyard of them all, North Vancouver’s Burrard Shipyards, originally Burrard Dry Dock Ltd. With neighbouring North Van Ship Repair and Yarrows Ltd., both of which it ultimately absorbed, Burrard built and repaired an amazing 450 ships, providing vessels for both the Royal Canadian and Royal Navy during both world wars.

It began humbly enough with William “Andy” Wallace building fish boats in False Creek in 1894. By 1914, Wallace Shipyards was operating out of larger premises and, having survived two fires, ready to take up the country’s call for six large cargo schooners and three freighters—the first deep-sea steel-hulled ships built in Canada, Wikipedia tells us— and shell casings.

Officially Burrard Dry Dock Co., as of 1925, installed Vancouver’s first floating dry dock; among its notable commissions during the ‘20s were the RCMP’s St. Roch, which would become the first ship to navigate the legendary Northwest Passage from west to east, and the first ship to circumnavigate North America.

The company really hit its stride with two shipyards during the Second World War, building 109 Park and Fort Liberty-class freighters, corvettes, minesweepers and landing craft while also outfitting 19 escort carriers for the Royal Navy. All of this required 14,000 workers, 1000 of them women.

Wartime Burrard Shipyards coppersmiths Miss Fauna Tomlinson and Glen Archibald, left, Mrs. Henriette Hall, of the engine fitting department, 1943. —Vancouver City Archives

By 1967 Burrard had acquired Yarrows Shipbuilders, North Vancouver Ship Repairs, and the Victoria Machinery Depot. Changes of ownership and names continued through the 1980s. But 1992’s cancellation of a heavy-duty icebreaker program for the Canadian Coast Guard brought bankruptcy to what was then Versatile Pacific Shipyards.

Only the floating dry docks continue in service, but under new ownership.

The new millennium brought dramatic changes to this North Vancouver industrial waterfront: condos, hotels, commercial space and public amenities. Developers agreed to preserve three shipyard buildings, two cranes and the stern and steam engine of HMCS Cape Breton, built by Burrard in 1944.Hopes for a National Maritime Museum on the site fails for want of federal funding.

As of 2010, “The shipyard cranes have been restored and now tower over the development... Signs and dioramas around the site tell the history of the former shipyards.”

* * * * *

Which brings us full-circle to BC Ferries.

As automobile traffic grew so did the ferry service by adding the Ministry of Transportation and Highways’ smaller coastal routes to its portfolio, building more vessels and enlarging seven of its existing fleet by stretching and elevating them to increase their car-carrying capacity.

Launch of the BC Ferries’ Queen of the North at VMD in 1970. —BC Archives

Three used ferries were added to what had become popularly known as the Dogwood Fleet and, in the 1990s, came the ‘Fast Cat” scandal: three high-speed catamaran ferries that exceeded their budget by two, suffered from technical difficulties, then proved unsuitable for their intended purpose and were sold at a fire sale price to offshore buyers.

BC Ferries’ long established reliance on provincial shipyards totally crumbled in 2004 with the corporation’s decision to disqualify all Canadian bids for three new Coastal-class ferries in favour of European shipyards. By buying in Germany, said CEO David Hahn, the corporation would save almost $80 million and offer lower ferry fares.

As opposed to the benefits of supporting the B.C. shipbuilding industry with its 100s of local jobs and those of marine suppliers.

BC Ferries then ordered a fourth vessel from the same German shipyard. Since then, with more of its fleet slated for retirement, four Polish-built Salish-class ferries have joined the fleet and, as of now, four more have been ordered, this time from China.

To no one’s surprise, protests by the B.C. building trades and at least one major Canadian shipyard have been vocal but, based upon the performance of recent years, BC Ferries will carry through on its offshore building program. At the time of writing, there are 42 shipyards of varying sizes in B.C., six in Victoria and six in North Vancouver.