The Legend of the Lost Golden Bullets Mine

A lone miner at work on his placer claim, B.C. location unknown. —Author’s Collection

“Gold! Gold! Gold!”

All these years later, I can see and hear him now. The late Jack Fleetwood, the man with the photographic memory, the man fellow local historians regarded as the Oracle of the Cowichan Valley, was addressing a small gathering of the Shawnigan Lake Historical Society.

An audience so small that it could fit in a lakeside boat house, the SLHS having just been founded by the late Brownie Gibson and several fellow history buffs.

Resting on his good hip, hand on the other, Jack began slowly, pausing between each exclamation for dramatic effect. His subject, gold mining on Vancouver Island, held his audience spellbound for there’s nothing more guaranteed to catch a listener’s ear.

Particularly when it’s a tale of gold being lost and found in years gone by...

Gold, to varying degrees, exists in virtually every stream on the Island and many are the tales of its having been found in quantity then ‘lost’ again through the discoverer’s death or by some other misadventure.

A century and three-quarters ago, the first whites to settle in the Cowichan Valley were, for the most part, settlers, here to farm. Sam Harris came to found a township at Cowichan Bay. But he wasn’t all business.

Not when he heard the stories of gold nuggets from a cave near the head of Cowichan Lake, nuggets moulded by the local Natives for use as bullets! Off he went in search, but he didn’t find the cave nor did, so far as is known, others who tried.

But the legend of Cowichan Lake country’s Lost Golden Bullets Mine lives on.

* * * * *

If there’s another star player in this drama besides Sam Harris, it’s an almost phantom-like character known by several names, but generally identified in old records as Tomo Antoine.

He was real enough, but records refer to this full-blooded Iroquois by several aliases which, it should be noted, weren’t attempts at deception on his part but the result of some confusion and misidentifcation by his Hudson’s Bay Co. employers, among them Chief Factor James Douglas.

The consequent confusion, and Tomo’s habit of flitting in and out of the old records, prompts my allusion to his having been as much phantom as man.

Now for the legend of gold bullets and a lost mine...

It was in 1859 that Tomo Antoine, in the HBC’s employ as a guide and interpreter who’d learned to speak several regional Indigenous dialects, heard or was told a tale of such a mine from the Natives of Kaatza (Cowichan) Lake.

He was told of a cave beyond the head of the lake where an exposed seam of gold in a cave yielded nuggets big enough to use in place of lead which had to be traded for from the whites. It took neither technological skills nor tools to heat the nuggets over a camp fire then mould them into musket balls.

(Author’s Note: In all written accounts, most of them sketchy, this is the accepted genesis of the Lost Bullets Mine: Tomo Antoine being informed by a garrulous informant. There appears to be no reference to his having been shown or having acquired a sample bullet—but I’m nitpicking as Antoine was regarded by most as a knowledgeable and reliable source before he was besmirched by marital and legal troubles—another story for another day.)

1859, it should be remembered, was a time of high gold excitement, an estimated 30,000 foreign (mostly American) miners having invaded the B.C. Mainland a year before in response to the discovery of gold on the Thompson and Fraser rivers.

But it’s not as if Antoine advertised the story nor did he, so far as is known, go looking for the mine; it was just one of several fascinating Native tales he heard from a variety of source, something to chat about around a camp fire. Which likely explains why it was 1861, two years later, before Sam Harris who’d settled at Cowichan Bay and was busy building what he hoped would become a townsite heard the story of golden bullets and resolved to seek out their source.

Sam Harris’s humble hotel and saloon at Cowichan Bay, the John Bull Inn. —Author’s collection

Besides trying to create a bay-side community Sam served as a special constable, but he still found time to go prospecting. On February 7, he headed up Cowichan River, panning as he went. His first signs of ‘colour’ were in a gravel bar near Quamichan Village, a long way downstream from the head of Kaatza Lake.in his ship.

It was, to say the least, an encouraging sign.

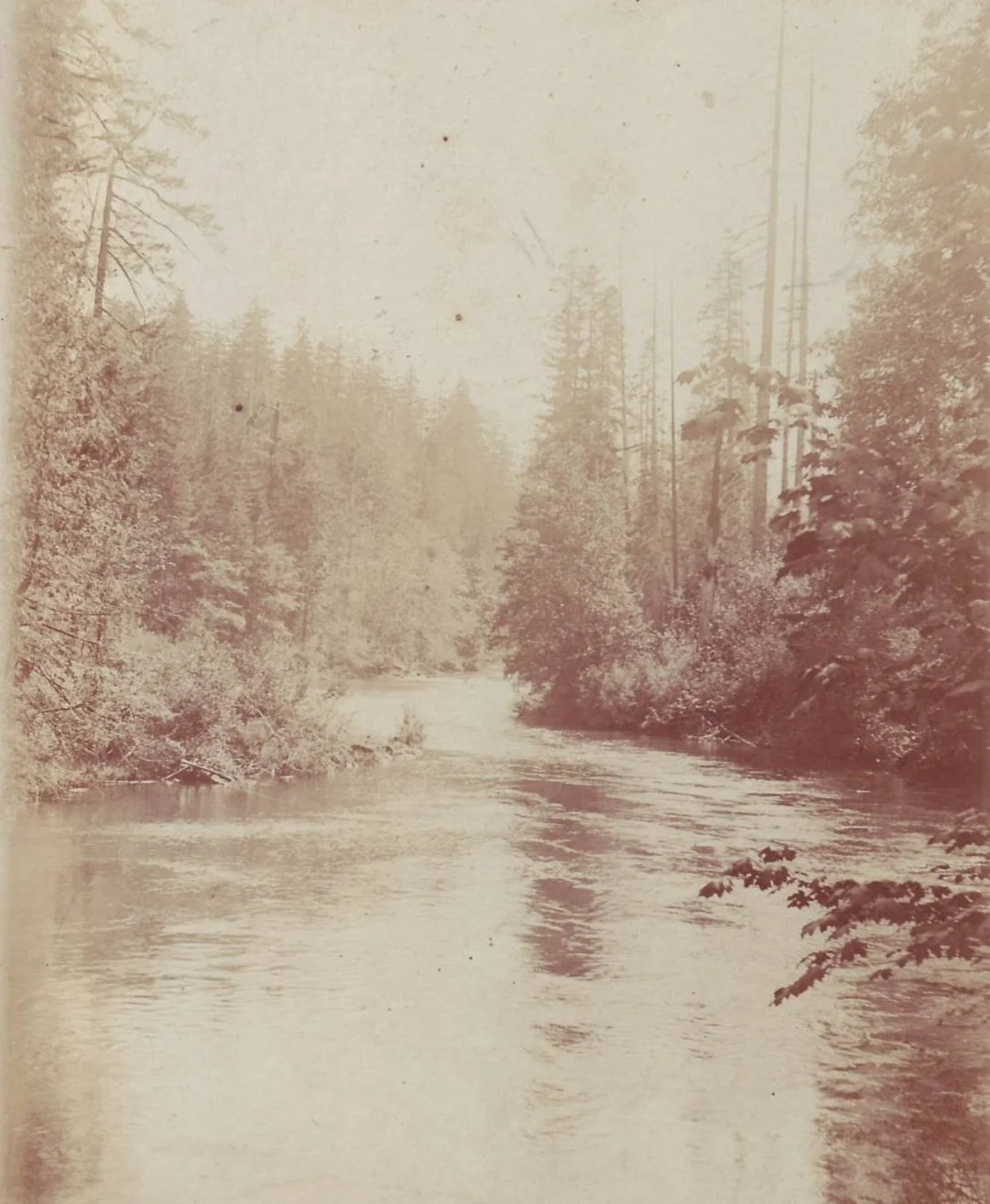

An early and rare view of the Cowichan River from the Dwyer family, shown here in full flood. It was high water that first foiled Sam Harris in his attempts to seek out the lost gold mine beyond Cowichan Lake. —Author’s collection

But February was also the season of high water so he decided to wait until later in the year. On July 20th, he again set out with two companions named Langley and Durham, and two Native guides. This time, at Quamichan, Harris met opposition from tribesmen who were opposed to their continuing.

Ignoring threats, the prospectors pushed on but were followed by warriors who managed to induce one of their guides to desert the expedition. Nevertheless, 11 days later, Harris and company reached the lake. Most promisingly, they’d found colour every time they dipped and swirled their gold pans.

But it was a distressing scene that greeted them at Kaatza.

Many of the locals had contracted, or just died from, dreaded smallpox. The chief informed Harris that he and his followers had resolved that, rather perish miserably, they’d die in battle by attacking a neighbouring tribe. Harris, remembering his duty as a constable, immediately shelved prospecting plans and offered to go for “medicine”.

It was mid-August before he was able to return to the lake with medical supplies (smallpox vaccine isn’t mentioned) and, as his interpreter, Tomo Antoine.

After he’d performed his Samaritan mission, Harris asked the chief about the source of the golden bullets. He was again stymied by the river, the chief explaining that, this time, the water was too low to paddle a canoe beyond the lake and it would take too long to hike overland.

More pressing, in the chief’s mind, was gathering and storing foodstuffs for winter.

For all of Antoine’s linguistic abilities, he couldn’t convince the chief to do otherwise. Not even the offer of Harris’s gun was enough to change the old man’s mind so, again disappointed and empty-handed, the expedition returned to Cowichan Bay.

A frustrated Harris hadn’t lost faith in the stories of a “quartz lode” beyond the lake but as for looking for it himself, he was done; he told others of the lost bonanza and returned to his own world of ‘Harristown’ aka ‘Harrisville’ aka ‘Harrisburg’ with its saloon, John Bull Inn/Hotel, a flagpole and (he was a constable, after all) a flagpole and a jail.

Perhaps some of the John Bull’s clients, regaled by Harris’s glowing tales of a gold mine beyond the head of the Great Lake, gave it a go but it was still generally accepted that if you wanted to mine gold you had to go to the Mainland.

Not that others hadn’t tried.

First to do it on the island’s west coast, according to legend if not physical evidence, were the Spanish. Today’s San Juan River was originally Rio del Oro—River of Gold—perhaps the product of wishful thinking. In 1852, as we’ve seen in recent Chronicles, there was a short-lived and tumultous stampede to the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii), primarily by Americans. Much to the relief of the Hudson’s Bay Co., it was a bust.

Closer to home, an article in the Victoria Colonist referred to a party of five “explorers” (not Harris and company) who’d returned from an eight-day-long expedition during which they’d “visited several islands between here and Chemainus” and brought back a “very fine specimen” from one of three veins of bituminous coal they’d discovered on an unnamed island.

They’d also found evidence of copper on the Vancouver Island shore besides other specimens which supposedly contained silver ore. Six miles up the Chemainus River the prospectors had recovered “from two to six colours of gold in every pan of gravel washed”. Before being turned back by high water, they noticed further evidences of coal seams.

Upon their return they stopped in to see Sam Harris, the Colonist identifying him as the area’s Indian Agent.

In December 1863, a brief news report in the Colonist noted the discovery of some “very encouraging assays” of gold and silver bearing quartz adjacent to the subsequently named Goldstream.

But it was the promising signs of copper that drew the most interest at that time, igniting what the Colonist described as “copper fever.” It held so much promise that the newspaper salivated at the potential. Copper mining would “inaugurate a branch of industry that will require immense capital and thousands of miners, and produce a staple article of commerce for thousands of years[!]”

There was no mention in these news reports of the Lost Golden Bullets Mine.

But the possibility of rich gold deposits were still on the radar; the answer for those impatient to know what, if any, treasures awaited discovery and exploitation, was thought to be the Vancouver Island Exploration Expedition of 1864. Its goal was to determine, in the words of an anonymous letter writer to the Colonist, “whether our island is auriferous [containing gold] or argentiferous [containing silver] or both”.

Because talk of conducting a geological survey of the Island had been going on for years without result, Colonial Governor Arthur Kennedy jump-started the process by offering to match from the colonial treasury every dollar put up by private interests to finance the VI Exploration party.

Thus, on June 7, 1864, the “wondrously motley” expedition as it was described by leader Robert Brown, sailed from Victoria, Cowichan Bay-bound, aboard the gunboat HMS Grappler. Only one among the seven members which included botanists and an artist to record their activities, was a professional prospector, ‘Yankee’ John Foley.

And, as interpreter and guide, the indispensable Tomo Antoine.

It was Governor A.E. Kennedy’s offer to match, from the colonial treasury, private financing of an official expedition that set a scientific exploration for the Island’s mineral wealth in motion. —Wikipedia

From the mouth of the Cowichan River they proceeded, over a week, to Kaatza Lake where they weren’t long in finding promising signs of mineralization. Just 10 days out of Victoria, Brown wrote in his journal that the experienced Foley had found extremely fine gold worth three and four cents a pan in a creek flowing into the lake and, three days later, “a perfect Mountain of Copper ore and ironstone”.

Exciting as these finds were, the expedition’s mandate was to cover as much ground as possible and, to that end, Brown split the party in two. His team would drop down the Nitinat River from the western end of Cowichan Lake to reunite with second-in-command Lieut. Peter Leech’s party at Port San Juan (Port Renfrew), the latter having proceeded there by way of Cowichan Lake’s southern shore.

All became “wild with excitement” when it was learned that the Leech company had discovered gold in a tributary of the Sooke River that bears Leech’s name to this day.

So great was their excitement, in fact, that Brown feared his men would desert him for the potential diggings. But they all held in (other than Foley who was fired for pulling his knife on a fellow explorer), and carried on through the Comox and Alberni valleys. It was fortunate for Brown that they were unaware that, in the meantime, in Victoria, the news had sparked what would be Vancouver Island’s greatest, albeit short-lived, gold rush to Leech River.

Their last mineral discovery was a 100-foot-long seam of coal beside the Puntledge River. Upon their return to Victoria after four and a-half months in the field, Victoria’s Daily Chronicle termed their efforts a brilliant success.

Sam Harris’s days of prospecting were behind him by this time, Brown having dismissed him as a drunkard, and, ill, he returned to Victoria where the former Life Guard of “magnificent physique” died of paralysis a few years after.

Again, in all of the news and excitement resulting from the VIEE, not a word about the fabled Golden Bullets Mine of Kaatza/Cowichan Lake.

As for gold mining in general, the great Privateer Mine of Zeballos in the 1930s and ‘40s yielded between 200-300 ounces per ton in extremely fine veins, proving that gold does exist in substantial quantities on the Island. Most Island gold mining operations, however, have been placer claims—the Leech River remains staked, mostly by weekend hobbyists, all these years later!

As well, there were brief flurries of gold mining activity in Alberni’s China Creek area in the 1890s and 19‘20s.

All of which begs the question: does the Golden Bullets Mine exist or is it myth?

In his 1999 history of Cowichan Tribes, Those Who Fell From the Sky, history professor Dan Marshall retells a tribal legend of gold and Spanish “Keestadores.” According to the elders he quoted, both gold and copper were long known to local Natives, the latter prized for its usefulness, the former being viewed as all but worthless.

But, at some point in the past several centuries, the crew of a Spanish galleon learned of the presence of gold and proceeded to do what the Spanish had always done in Central and South America: capture and enslave the local inhabitants as forced labour.

It was with great difficulty that the Cowichans were able to overthrow their oppressors and kill them to a man. But the source of the gold which they were forced to mine obviously hasn’t been passed down to succeeding generations.

Was it the Lost Golden Bullets Mine of Cowichan Lake?

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.