The Monster and Mrs. Bings

I had no intention of following last week’s post on the Westwell’s tragedy with another tale of violent death by human hand.

And I wouldn’t want last week’s tale of a family tragedy brought on by mental illness to be equated with this week’s story—which is nothing less than a home-grown replay of the most infamous serial killer of all time, Jack the Ripper.

No, I must lay the blame on the ‘Visual Storytellers,’ an offshoot of the popular online nostalgic Facebook photo gallery, “You Know You’re From Duncan...” and their recent post about, of all sinister things, Duncan’s Holmes Creek.

* * * * *

Well over a century has passed since—but history hasn’t forgotten—the stormy night of Sept. 29, 1899, when matronly Agnes Bings met her death on a railway embankment beside Victoria’s Inner Harbour.

To this day, her murder must be the most bizarre—and brutal—in city record.

Despite the intensive investigation by two police departments and the continent’s most famous private detective agency, her fiendish killer was never captured, and the murder remains unsolved...

Autumn had barely begun but, with a violent sou’wester buffeting the city, it felt like a wintry night as John Bings waited anxiously in his Victoria West home. Although it was only 9 o’clock, his wife should have long returned from the Store Street bakery which she ran with her brother, William Jordan, who served as baker, Mrs. Bing acting as cashier.

Since a stroke had left Bings, who worked for the E&N Railway, disabled, the couple had had to rely upon the little bakery, of which his 44-year-old wife had managed to make a modest success with John acting as babysitter to their young son.

But as the minutes ticked by, he became increasingly concerned.

An artist’s depiction of a “Suspicious Character” in an 1888 issue of The London Illustrated News. But the outfit of the man to the left is totally out of sync with the 100’s of artists’ and photographers’ conceptions of the real Jack the Ripper who’s almost always shown in a full-length overcoat, wearing a top hat and carrying a medical bag. And note the man in the deerstalker cap—Sherlock Holmes?

Agnes usually closed the shop at 7:30 and crossed over the E&N Railway bridge. (Until it was demolished in recent years it spanned the harbour narrows immediately north of the Johnson Street bridge,) She’d then cut through the sprawling Songhees Reserve on the west side of the harbour and complete the half-mile trek to their home within half-an-hour.

But more time passed and, without a telephone, Bings had no way of knowing what had delayed her.

Finally, at midnight, convinced that she’d decided to stay in town because of the storm, he retired, although, as he later told a coroner’s jury, had he been able to, he’d have gone looking for her.

With dawn, he was up and sent word to those of their friends with whom she’d have been likely to stay. Upon learning that none had seen or heard from her, and by now almost panic-stricken, he notified police. Const. Robert Walker answered his plea for assistance and set out to trace the missing woman’s anticipated movements from when she’d have set out for home.

From Wharf Street Walker crossed the bridge and continued along the railway track to the rock cut over what’s now Esquimalt Road, where the right-of-way forked to the right and crossed what was then the Songhees Reserve.

It was 9 o’clock when Walker’s attention was drawn to a battered form in the hollow. To his horror, it was the nude and mutilated body of Agnes Bings.

Never before had the Victoria Colonist, its previous rhetoric notwithstanding, had to publish details of a crime that “for fiendishness and mysteriousness has seldom been equalled in this part of the world.”

According to the Sunday morning edition, “On Friday evening between 7 and 8 o’clock a woman was cruelly murdered on a well-travelled thoroughfare and within a few yards of occupied houses and not until 12 hours later was her body found, so that the murderer had lots of time to cover up his tracks and get well away from the scene of his crime…”

(Incredibly, at least by today’s journalistic standards, this story of the grimmest atrocity in Victoria history was buried on page six, the Colonist having given front-page notice to the worsening political troubles in South Africa).

“The victim of this terrible murder, the details of which are too revolting for publication (two days after, in covering the inquest, the newspaper would give the ‘revolting details’ in all their gore), was Mrs. John Bing [sic], a hard-working, industrious and eminently respectable woman, who with her brother, William Jordan, conducted a bakery on Store Street to support her invalid husband and eight-year-old son.”

According to the police report, Mrs. Bings had left the Store Street bakery sometime between 7 and 8 p.m. Friday as usual, to begin the lonely walk over the bridge and through the reserve to her Russell Street residence. Although the shortest route between town and home, it was, as the newspaper noted, “a walk that few women would care to take at night, but Mrs. Bing was used to it and besides being a great lover of her home, which she managed to keep in perfect order despite her long hours at the store.”

(This is the Victorian ethos at work here; Colonist readers were to have no misconception that Agnes Bings was anything less than a respectable, married woman—as opposed, say, to the Ripper’s victims who were prostitutes.)

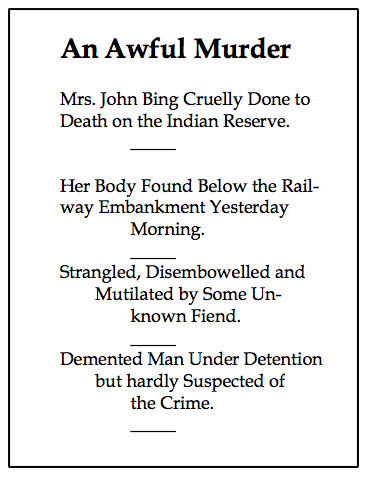

Such were the gruesome headlines that greeted Colonist readers on Sunday morning, Oct. 1, 1899. Incredibly, this story appeared on page 6, front page news being devoted to troubles in South Africa.

Almost a century and a quarter after, this section of the city’s waterfront has changed dramatically. The Songhees Reserve long ago yielded to the Ministry of Transport docks, then to industrial and expensive residential development. But some things never change. On the west side of the harbour, even with street lighting, businesses and massive apartment buildings and condominiums all about, Agnes Bings’ route to her home could yet be an unnerving walk for a lone woman at night.

For Mrs. Bings, as we know, it was her last. At the rock cut which today forms the intersection of Esquimalt and Tyee Roads, she was accosted by a monster in human guise.

At least, so the police surmised, as it was here that her body was found, beside the railway embankment, at the base of a telegraph pole.

(When I retraced Agnes Bings’ route years ago, there was still a telegraph pole there because it doubled as an E&N milepost.)

Her hair was dishevelled, “showing that she had made a desperate fight for her life,” and death apparently had been caused by strangulation; Dr. R. L. Fraser surmised this by the deep furrows in the victim’s neck, which indicated either near-superhuman strength on the part of her killer, or that he’d used a rope or strap to do the deed. The ridges in her windpipe had been caused by such pressure that strands of her hair remained impressed in the folds where the murderer’s thumbs or garrote had been pressed.

(So much for the Colonist’s vow not to give gruesome details.)

Perhaps the single redeeming feature of the atrocity was the fact that Mrs. Bings was dead before she was disembowelled.

Robbery was at first considered because two rings had been taken from the victim’s hand. This apparent motive was reinforced when Victoria police, under Chief Harry Sheppard, and the provincial police under Supt. Fred Hussey, discovered her purse in the E & N. yard, on the eastern (town) side of the bridge. Thought to have contained six or seven dollars, it was empty. Police considered it possible that the killer’s first thought had been robbery but, when Mrs. Bing, although described as being of slender build, fought back, he’d lost control.

The location of her purse did, at least, indicate that the killer had returned to town.

Of one other fact the police were convinced: the slayer was a madman. This in mind, they proceeded to round up and question every vagrant, derelict and resident with a history of erratic behaviour; those whose answers seemed vague were detained “to keep them out of harm’s way”.

Due to the location of the murder, there were those who took it for granted that the responsible party was Indigenous, although police at first thought, condescendingly, that this unlikely as “Indians [sic] seldom or never commit murder without provocation, and when they do, do not mutilate the body in the way Mrs. Bing’s was.”

Hindering the investigation most was the matter of Friday night’s storm, when few were afoot, particularly in such a lonely area.

Worse, the heavy rain had erased any possible evidence such as footprints, having been so heavy that it had washed away all traces of blood near the body.

“Rumors of all kinds were rife during the day, the community being considerably worked up over the tragedy,” editorialized the Colonist, “and there was quite a rush to the police station when the report circulated that the murderer had been arrested.”

Unfortunately, it turned out to be but one of many fruitless leads.

From the start, police had felt there was little connection between Charles St. John, an itinerant labourer from California, and Mrs. Bings’ murder. It had been during one of the detectives’ several trips to the murder scene that they’d observed St. John, sitting in a corner of the E&N yard on Store Street. Not 10 yards away, they’d discovered Mrs. Bings’ empty purse. This, plus the fact that the 31-year-old gave evidence of being mentally disturbed, prompted his arrest. After a medical examination, he was thoroughly interrogated, officers learning than he’d recently quit his job as woodcutter on a Colwood farm to hike into town “on account of some illusion which he says drove him from his camp”.

For days, he said, he’d lived on nothing but bread and water—his cure for leg cramps—and had divided his time in town between a View Street cottage owned by his father, and Beacon Hill Park. Most people seemed agreed, if reluctantly, that “the police will have to look further than St. John for the perpetrator of the crime, and to do this they have a difficult task before them”.

Others recalled the brutal strangulation of a woman known as Mattie Crow, several years before, at a time when similar murders had plagued police in Denver and San Francisco. More recently, the nude body of a Native woman had been found not a hundred yards from where Mrs. Bings was murdered. Investigation had revealed, however, that her death had been due to natural causes and it was surmised that her clothes had been stolen.

By the following day, police had little more to go on than they had when Const. Walker discovered the body.

If only briefly, they’d considered the possibility that a resident of the reserve was responsible, noting that many visitors from northern tribes called at and departed from the local Songhees encampment at all hours. This slender theory was prompted by the discovery of a basket containing some dried fish, a can of fish, and some freshly-picked wild peas near the murder scene. Because, as was far more likely to be the case, the basket having been found on the reserve would seem to weaken its potential as evidence, authorities admitted that it was “a rather vague clue to work on”.

Consequently, investigators turned their investigation to searching for two crucial leads: Mrs. Bings’ missing clothing—which the murderer evidently had carried away—and her jewellery.

For some, the fact that most of her clothing was taken seemed to strengthen the argument that the culprit, or culprits, had been from the reserve. But police, at least showing some imagination, considered another fascinating possibility: that the murderer, who, by all indications, had returned to town, had dressed himself in Mrs. Bings’ clothing!

Armed with a description and sample of the victim’s costume, officers even searched the harbour vicinity with grappling irons but failed to find trace of the garments which, due to the over-dressed fashions of the day, would have formed “quite a bundle”.

The second day of investigation ended with the pronouncement by doctors who’d examined the body that the murderer was undoubtedly a sex pervert, and with a statement by police to the effect that they were convinced that the murderer, or murderers, had fled from town on Friday night before discovery of the crime, by canoe or by boat.

This much all could agree upon: that the killer “must have been very powerful, or had the temporary strength of a madman. The murdered woman was strong and robust, and it goes without saying that she made a desperate struggle to save herself, not giving in until the rope or strap with which she was strangled had been tightly drawn around her neck.”

(The postmortem mutilation had been effected with a knife, said Dr. Fraser.)

If nothing else, the police were enthusiastic; several officers volunteered their free time to the case, and proceeded to track down leads, however small. Detective Palmer and Const. Murray of the Provincial Police even rushed to Esquimalt ‘s Halfway House to question an obnoxious drunk.

Cooperation between the city and the provincial police forces didn’t go without some friction, however, at least as far as the Colonist was concerned, because the Songhees Reserve had become something of a jurisdictional no man’s land.

The coroner’s inquest, held on October 2nd, did offer some surprises to the public.

Biggest of these was Const. Redgrave’s testimony that Mrs. Bings’ purse had been found on the west side of the harbour, not in the E&N yard as previously stated. Her hat had also been found some distance from the body. Therefore it didn’t necessarily follow that the murderer had returned to town afterwards as had immediately been supposed by the newspaper and its readers.

Again, it seemed to suggest that someone on the reserve was responsible.

An ironic twist to the inquest testimony was provided by William Jordan, Mrs. Bings’ brother, who stated that she’d asked him to accompany her home to assist with a load of heavy parcels. He said he’d had to decline, as he had to return to work. He also said that she likely was carrying no more than 50 cents in her purse.

(Perhaps because there’s no further mention of her carrying parcels, she left them at the bakery.)

The tragedy became low comedy when a Dr. Dumain and his 21-year-old “sensitive,” a Miss Agnes Harris, held a séance at the murder scene. Miss Harris proceeded to recreate the crime and to describe the murderer and his subsequent movements, in gory detail, As reported, “after waiting silently for eight minutes, she proceeded to describe the coming up the railway track of the man and woman, describing the clothing of the former with minuteness.

“There came a blur and then she saw the murder[er] wipe his hands on the dead woman’s stockings and start for town. He paused, she says, at the end of the trestle and again in the centre of the swinging bridge where he dropped the telltale stockings into the water.” She then described his movements about the waterfront as, in a panic, he attempted to find a departing steamer without success, when she “resume[d] her normal condition”. There, the seance ended after Miss Harris, her mother, Dr. Dumain enacted the murderer’s flight before a curious crowd.

After asserting “an aversion to notoriety,” the good doctor of occult sciences made a second and third attempt to re-stage the murder. He seems to have lost interest rather suddenly when a newspaper reporter, upon learning that Miss Harris was acting under hypnotic suggestion rather than in a self-induced trance, demanded to know how he, as hypnotist, knew so much about the crime.

Reasoning that the young woman could only report that which Dumain told her, the newsman found it highly suspicious that Dumain could describe the killer with such “minuteness”. The same reporter rather crudely recalled the strange drowning of the daughter of Dumain’s benefactor, a Mme. Heller, some time before.

Hence the doctor’s retirement from the Bings case!

With each passing day the clues became fewer and a special squad of city and provincial detectives, commanded by Chief Harry Sheppard, appeared to face a stone wall. Every lead, regardless how slight, that was followed up proved to be in vain. At least they’d finally ruled out the likelihood that the crime had been committed by someone on the reserve, as all who were in residence that night were able to account for their movements.

(Even allowing for the fact that it was late at night, that so many people could account for their activities seems highly unlikely if you think about it.)

The posting of a $500 reward brought forth no new information. On October 11th, the Colonist reported, “After a week and a half of work on the mystery surrounding the horrible murder of Mrs. Agnes Bings [finally spelling her name correctly], the police may be said to be not one step nearer the solution of the crime than they were at the outset of their investigations… The detectives in so far as this atrocious crime is concerned are working in the dark—and will be until accident perchance gives them the end of the thread to follow.”

But the “end of the thread” was never traced and, despite a short-lived report that Mrs. Bings’s slayer had been arrested in Saanich, the fiend remained at large.

Ironically, during the course of their investigation, officers had learned that, quite possibly, Mrs. Bing’s slaying might have been prevented.

The night previously, a young dressmaker employed in Spencer’s Arcade had been accosted by a “rough looking” man while following the same route taken by Mrs. Bings. Stepping out beside her, the stranger had asked if she were not afraid of the dark, at which Annie Duncan had ordered him away. Fortunately, at that very moment, she’d sighted two shipyard workers—as did her unwanted companion, who vanished into the dark.

Upon being informed of the incident, Const. Walker—the very City police officer who would find Mrs. Bings’ body—offered to accompany Miss Duncan to her home the following night, Friday. But, unnerved by the experience, Miss Duncan chose to remain in town with friends, and, at the very hour she’d have been crossing the reserve, with Const. Walker as escort, Mrs. Bings, walking alone, met a monster on the railway track.

* * * * *

At best the combined police investigation into Agnes Bings’s brutal murder could be described as ineffectual, although the odds of finding the killer with so few hard clues were intimidating. Among the many strikes against a successful conclusion was the heavy rain that had washed away potential clues at the murder scene, and the fact that on the weekend of the murder Victoria had hosted hundreds of American and Mainland visitors who’d come to watch a sporting event then returned to their homes.

For all that police did have a prime suspect.

73-year-old drifter and petty criminal named David McDonald Gordon, who appears to have been mentally unstable, had drawn suspicion to himself by talking about the murder—not just conversationally, but with what appeared to be with intimate personal knowledge. When questioned by police he denied his own involvement but pointed a finger at a man named Jim McCluskey who, he said, had left town.

It was almost common practice in those days for the province, when faced with complex criminal cases, and sometimes labour unrest that threatened the public peace, to hire a Pinkerton’s detective through that agency’s Seattle office. When Gordon was again sentenced to jail for petty theft, it presented an opportunity for B.C. Police Supt. Fred Hussey to have Pinkerton’s plant one of its agents in Gordon’s cell to befriend him and encourage him to implicate himself in Agnes Bings’ murder.

It’s interesting to note that, before beginning his undercover assignment, having read the Bings file given him by Supt. Hussey, “Agent Number Five,” actually “Mr. Sayers,” criticized the police investigation to date as superficial and the coroner’s inquest as non-productive. That aside, it was his job to gain cellmate Gordon’s confidence by boasting to him of having sexually assaulted women and girls. Gordon proved to be a keen audience, one who obviously enjoyed stories of perversion. But he just listened rather than spoke of his own dubious exploits.

Nevertheless, Sayers was convinced that Gordon was on the verge of confessing to the Bings murder when Gordon suddenly became ill and died in his cell of a hemorrhage of the lungs. If David McDonald Gordon did in fact butcher Agnes Bings a la the Ripper of several years earlier, he took the secret to his grave.

Within yards of this overpass (as it appeared in the 1960's), Victoria Police Const. Robert Walker found the mutilated body of Agnes Bings. 121 years later the mystery of this Jack the Ripper style murder remains unsolved.

Almost a century and a-quarter later, there are those who believe that Agnes is still with us, at least in spirit form.

Chris Adams, son of John Adams who has for years given ghost tours (www.discoverthepast.com) of Victoria’s Chinatown and waterfront, guides his own ‘Ghostly Walks.’ One of them includes the sad story of Agnes Bings and how, that storming night in late September 1899, she headed out from the Wharf Street bakery (the building’s still there) to walk to her home across the bridge (since demolished).

Five years ago, Chris Adams told a reporter that “Agnes Bings’s ghost has come back to haunt the place where her body was found which is now the Delta Ocean Pointe”. He’s referring to what now identifies itself as a Delta Hotels by Marriott Victoria Ocean Pointe Resort at 100 Harbour Road. [I think Chris is being less than literal on this point as newspaper reports were quite specific in identifying the telegraph pole on the nearby E&N Railway track; this pole’s successor was still there when I retraced Agnes Bings’s route in the 1960s.]

But back to Chris Adams, who says that diners in the hotel’s lower restaurant by the harbour’s edge have reported seeing a “shadowy woman drifting along, pacing back and forth”. Some have said they’ve even heard her screams.

Why would Agnes have paced back and forth? She was walking home—perhaps almost running if she’d been accosted or had seen that she was being followed? We can accept that she did indeed scream if only momentarily. Be the hotel haunted or not, I don’t see a connection here other than that the murder scene is close by...

Which, finally, brings me around to where I started with my reference to the Cowichan Visual Storytellers and their tale of Holmes Creek, courtesy of local historian Sylvia Smith who’s lived in the immediate area for decades.

John and Agnes must have been planning ahead for his premature retirement because of his disability. They were going to settle in the Cowichan Valley on part of the Holmes Estate, Duncan. Instead, Agnes was brutally murdered and John, who never regained his health, died an indigent in the Old Men’s Home, immediately adjacent to (of all places) Ross Bay Cemetery.

There, in due course, he was laid beside Agnes in a grave that until just a few years ago was unmarked. Happily, thanks to the promotional efforts of the Old Cemeteries Society, family descendants living on Saltspring Island became aware of the story of Agnes’s death and paid to have a headstone installed.

That was something I’d vowed to do with any revenues from my book on murders which I still haven’t completed.

* * * * *

Readers wanting to do something different and highly enjoyable can participate in their own GhostlyWalk (ongoing despite COVID-19) by contacting John and Chris Adams at discoverthepast.com.

According to Chris Adams of Ghostly Walks (discoverthepast.com) poor Agnes Bings hasn't found peace but is often seen, pacing back and forth and screaming.

I can assure you from my own experience that their nightly tours of downtown Victoria’s often seamy past are outstanding.

PS: The late Duncan author David R. Williams devoted much of his book, Call In Pinkerton’s: American Detectives at Work in Canada, to the famed agency’s Seattle office’s assignments for the British Columbia government. But he doesn’t mention Agnes Bings, Agent Number Five or suspect David McDonald Gordon.

A pity.

Footnote:

The real Jack the Ripper murdered at least five women, all prostitutes, between August and November 1888, in or near the Whitechapel district of London’s East End. His last known slaying occurred three years before Agnes Bings’s eerily similar murder in Victoria—more than enough time, as some have speculated, for Jack to arrive in Victoria, British Columbia’s little corner of olde England. Others have attributed the injuries inflicted upon Mrs. Bings to the work of a copycat killer.

There have been 100’s, perhaps 1000’s, of serial killers throughout history but Jack the Ripper is the most infamous of them all.

For decades Agnes and John Bings shared an unmarked grave in Victoria's Ross Bay Cemetery. Thanks to a tour given by the Old Cemeteries Society (https://oldcem.bc.ca/) a family descendant came forth with the funding for a headstone.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.