The Mystery Tunnel of Leech River

I wrote the following chapter in 1971 based on articles I’d written for the Colonist weekend magazine in the 1960s.

The information contained within has been repeatedly pirated and published ever since. You may have read some or much of this elsewhere but I wrote it first and, like any prospector worth his salt, I am staking my claim to it!

* * * * *

Does a mystery tunnel, complete with steps carved into a solid rock cliff—with a cache of gold bars—exist in a Vancouver Island rain forest?

The answer to this question would solve what must be one of the most intriguing tales of lost treasure in British Columbia history—and the key, like that to 'Rattlesnake' Dick Barter’s alleged hoard (another story for another time)—lies within 25 miles of Victoria!

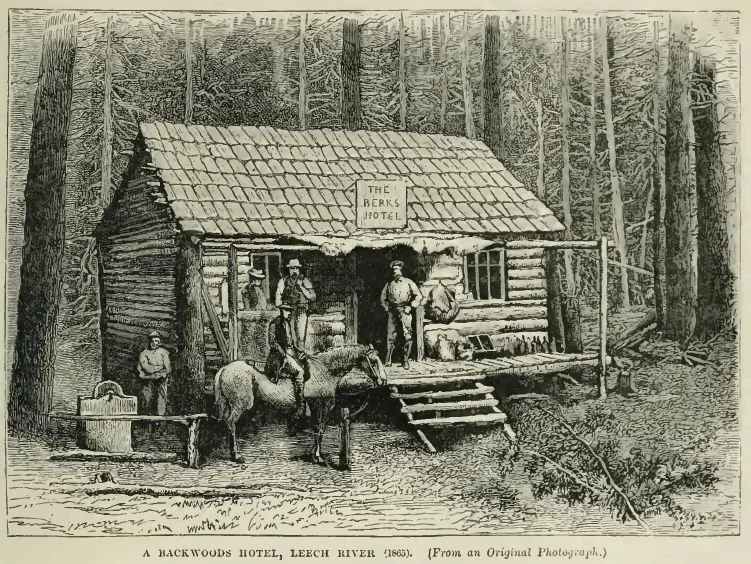

Vancouver Island’s first gold rush occurred on the Leech River in the early 1860’s but the Spanish have long been rumoured to have searched various locations for the precious metal in the 1700’s. If so, these miners lolling about Leechtown’s Berks Hotel were latecomers! —Author’s Collection

The most important chapter of this story is quite well known locally, and began in 1961 when the late Ted Harris, then a reporter for the Colonist, heard a tantalizing story from a friend. The friend had told him of an old prospector named Ed Mullard and, subsequently, Harris confirmed the fascinating details with Mullard himself.

Sometime before—it’s not recorded when but in the late 1950’s—Mullard and a partner had been prospecting in the historic Jordan Meadows-Leechtown region. Situated to the northwest of the one-time mining and logging camp, between the Jordan and Leech Rivers, Jordan Meadows is a triangular quilt of trees, meadow and swamp.

Long ago, a family named Weeks, after whom 'Trout' Lake was rechristened, homesteaded here, but virtually all traces of their substantial home and outbuildings have disappeared. Today only loggers, outdoorsmen and an occasional prospector visit this region, much of which floods in winter.

But to return to our story: Late one afternoon, Mullard left his partner to hunt deer. Finding a fresh track, he followed it through the undergrowth. Night descends rapidly in late autumn, however, and dusk ended the hunt prematurely.

It was snowing when Mullard headed back to camp, elbowing his way through chest-high salal. Suddenly, the prospector was astonished to find himself descending a staircase; he later described the uncanny experience as “just like walking into a cellar”! Shouldering aside the salal for a better view in the failing light, he notoiced an oblong hole in the cliff side.

Peering into its murky depths, he could see another series of steps, seven in number. Beyond was an arch and a rectangular gallery about 10 feet in length, and high enough for a man to stand upright (Mullard was about six feet tall).

Overcome by curiosity, in the feeble glow of matches, he inched along the silent passage, down the second staircase and into the gallery. At its far end, in the right wall, the scene was repeated: another “beautifully carved” arch, seven more stops and a second gallery.

Here, however, Mullard encountered water shin-deep. Beyond the dancing pale of his match, he detected what appeared to be yet another gallery and, he told one close acquaintance, he could “hear water rushing.” Rather than explore further, he retreated to the entrance, memorized its location, and returned to camp.

(This acquaintance, some years after, recalled Mullard’s reaction to his discovery as having been “astonished, overjoyed”).

But Ed Mullard didn’t live to see the mystery shaft again and, as far as is known, no other man has set eyes upon it since that autumn evening of 60-plus years ago.

Reporter Harris having heard of the wondrous tale in April 1959, called on Mullard. According to the Colonist account of 18 months later, “The old man told him [Harris] a great deal—perhaps more than he’d told anyone else—and readily agreed to take Harris right to the spot.” Mullard and Harris made their pact in the spring of 1959 but, because of unsettled weather, decided to wait until June. A month before they were to go, Mullard died suddenly.

Which is where our mystery really thickens as, although Mullard had told Harris more than he’d divulged to anyone else, he hadn’t revealed the tunnel’s exact location. The Colonist nevertheless agreed to sponsor an official expedition on the basis of seven clues which Harris had gleaned from his conversations with Mullard:

The area is between Leechtown and Jordan Meadows;

It’s somewhere along a shorter route than the regular trail between the two, because Mullard spoke of a shortcut home;

It’s at the foot of huge rock bluffs;

It’s on ground that isn’t very steep for the opening is almost horizontal;

It’s among heavy undergrowth on shallow soil, for it was overgrown although cut into granite;

It’s a substantial distance from Leechtown, for Mullard spoke of hoping to get to the site and out again in one day but being prepared for a two-day trip, just in case;

It’s in high country, for he mentioned it overlooking Jordan Meadows.

Using Mullard’s clues and aerial survey photographs, the Colonist organizers narrowed down the target area to the southwest face of Survey Mountain. This, because “the only rock bluffs [remembering Mullard’s description] of any consequence” are to be found here. “At the foot of the bluffs is a shoulder—at about the 2,700-foot level—roughly 100 to 200 yards wide and several miles long. All clues point to the shaft being somewhere along this shoulder,” wrote newsman John T. Jones.

That Remembrance Day weekend, representatives of the provincial museum, Colonist staff members, members of the provincial forest service, and volunteer university students began the arduous task of scouring Survey Mountain’s southwest face.

Assisted by a helicopter and walkie-talkies, the dozen hunters worked diligently for three days until defeated by fog and the season’s first snowfall. As they ruefully noted, it would take an army to find anything in this rugged terrain.

Upon their return to Victoria, searchers had been in good spirits and optimistic. However, despite talk of returning the following year, the hunt was never resumed. And, officially, the situation remains unchanged to this day.

Several years ago, I interviewed a close friend of the late Ed Mullard who asked me not to publish his name, to which I agreed. He then told me a fascinating tale of lost treasure and of a “curse”. About a year after Mullard’s passing, he told me, Mrs. Mullard had informed him that her husband had bequeathed to him all of his outdoor and prospecting gear. When he’d examined his inheritance, he made some interesting discoveries—discoveries which were to send him packing into Jordan Meadows time and again. This is his story:

Unlike reporter Harris’ information, he said that Mullard hadn’t been alone on that momentous day but had been accompanied by a man named McLaren. Upon stumbling onto the steps, both men had peered curiously into the tunnel. But only Mullard had had the courage to grope along the shaft, McLaren standing nervous watch at the entrance.

Perhaps the unholy circumstances of their discovery, or the waning daylight slightly unnerved McLaren; perhaps he simply maintained a healthy mistrust of old tunnels and caves. Whatever, when Mullard explored the strange steps and galleries, he was alone.

Upon encountering water, he’d returned to the entrance, cut some saplings and split the ends. Then, with these crude “chopsticks,” he’d again ventured through the black hallways. Despite the awkwardness of his saplings, he ‘d succeeded in snaring several relics of interest.

These items—said this informant—were found in Mullard’s effects, along with instructions as to how to reach the tunnel. Two of the recovered objects, which he showed me, were an old miner’s pick and the head of a hammer, both hand-forged and badly corroded. (Not unusual finds in themselves.–TWP)

Far more interesting was the third item which Mullard reputedly had retrieved from the shaft’s flooded floor—a small gold bar. This, I didn’t see.

According to Mullard’s friend, the ingot—“quite well made”—had measured approximately three inches long, one and one-quarter inches wide and an inch thick.

(It should be stressed here that, upon my sharing this information in the Colonist, Mrs. Mullard vehemently denied any knowledge of any gold of any description in connection with her late husband’s legendary tunnel. And no one, to my knowledge, has substantiated Mullard's friend’s claim to having seen—and handled—such a gold bar).

Also said to have been recovered by Mullard were some enormous, unidentified crystals.

Capt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, c. 1785. Whenever people talk about lost gold mines on Vancouver Island, speculation about the Spanish—who, as shown by their explorations and conquests in Central and South America, were obsessed with acquiring gold—comes up. —Wikipedia

Four days after his amazing find, Mullard was dead—again, according to this source. As for McLaren, terrified by his partner’s sudden demise, and apparently connecting it with the evil tunnel, he’d refused to discuss the matter with a soul and, when continually questioned, left town. (Again, according to this source.)

Following Mullard’s instructions, my informant had tried several times to locate the tunnel, succeeding only in finding one of the prospector’s markers, the initials “EM” in a stump. Asked why he was willing to reveal so much to me, knowing that I’m a writer, he’d replied: “Why not? I’ve got nothing to hide. I don’t give a damn who finds it.”

In March 1970, a Victoria logger telephoned me, requesting further information concerning the Mullard tunnel. He said that he’d been falling in the rumoured area about 1955. In the course of their work, he recounted, he and his fellow loggers had found it necessary to lower themselves on ropes about 200 feet down the south side of Survey Mountain.

The Leechtown/River area in context with Victoria, Vancouver and Seattle. —www.weather-forecast.com

Here they found a “cave,” with steps leading up to the entrance. No one had been equipped with lights, he said; these, however, proved to be unnecessary as daylight reached the end of the shaft, which apparently had collapsed. The loggers had noticed some ancient miners' tools but none was “interested in that short of thing in those days,”, and had returned to work.

This man’s interest hadn’t been aroused until a full 15 years after, when he’d heard of Mullard’s by-then famous discovery. He stated that he was sure he could remember the shaft’s location to within 1,000 feet, that it was now possible to drive to within a half-mile of the entrance, which was “well camouflaged” by the forest.

Our conversation had concluded with his saying that he planned to re-visit the site with a friend the following weekend, that he’d report his findings by telephone. But seven months passed and I didn’t hear from him again. Then it was reported that he’d been killed in a logging accident—on Survey Mountain.

Whether he got to investigate his “cave” on Survey’s southern shoulder, I cannot say.

Proof that there really is gold in them thar’ (Vancouver Island) hills. —www.youtube.com

There the story rested in 1971 and there, to my knowledge, it rests today. Rumours—growing wilder with each telling—still circulate Victoria, articles have appeared in newspapers, magazines and online, and interest in the mystery tunnel has spread throughout the Pacific Northwest—and beyond. For all that, if anyone is on the right track, or has succeeded in finding Mullard’s tunnel, he isn’t saying.

Some believe that Mullard's tunnel isn’t on Survey Mountain at all but closer to Sooke Lake and that it was submerged when the Greater Victoria Water Board raised the lake's level some years ago.

Some rumours go beyond the ridiculous. Such as that told this writer—in all seriousness—of Communist Chinese agents making regular midnight trips in and out of the nearby Sooke Lake watershed which is also reputed to have been visited by the Spaniards in the 18th century.

Another legend concerns a 'Spanish' cannon which, so the story goes, had been seen in the swamps of Jordan Meadows from time to time. Unfortunately, it would seem that the meadows shift like the desert sands, for no one ever sees it twice. Another tale of an oft-spotted but never-plucked relic is that of a bronze tablet or plaque in the fork of a tree which has grown around it.

Further legends of a Spanish monastery are inspired by Sooke’s Boneyard Lake, supposedly named after an Indigenous massacre. As with the other rumours, it has little apparent foundation; the name more likely comes from the fact that the Hudson's Bay Co. had a slaughterhouse here.

However, other reports are more credible—and as interesting.

One is the discovery of another 'cave' on Survey Mountain’s north side, in 1928. The cavern is said to be “quite spacious” and deep. The finding of a Storey's cigarette package indicated that it had been explored earlier. Would this cave have any connection with Mullard’s tale?

Somewhat farther afield, but of interest nevertheless, is the finding of a rusted cutlass near the Sooke Potholes, some years ago. When interviewed in March 1967, its owner said he couldn’t remember the details of his find beyond the fact the weapon had been lying in deep grass about a mile from the Potholes. A second blade was retrieved, 1966-1967, by another party, some two miles from the first discovery.

The pitted blade of the former is two feet long, curved and 1 1/4 inches at its widest point. No trace of the handle’s covering remains. Despite its obvious age and indicated exposure in Sooke grass, it was in good shape when I handled it. One of its more interesting features is the fact that the handle is too small for the “modern” male hand.

A glance through reference books in the Victoria Public Library would indicate the weapon to be of the late 18th century; it answers the description of both Spanish and British naval issue of that period. How did it come to be lost in the Potholes? Perhaps it had been put to other use—as a machete, perhaps?

By the time I began to explore historic Leechtown and area there wasn’t much left to be seen; this cabin dated back to the 1930’s or 1940’s. —Author’s photo

And the rumours live on…

All are tempting, few can be verified. I asked one man, who has done considerable research into the project including several field trips, if he really believed Mullard’s story. His reply: “Where there’s all that smoke there just has to be some fire.”

Conjecture as to the tunnel’s origin ranges from Inca artisan/slaves imported by Spanish explorers during the period of their Central American colonization, to confidence man Brother XII who ran a religious colony near Nanaimo during the 1920’s. (Patricia: please create link to previous post, Did Brother XII leave Mason jars filled with gold? ).

Did any of the 1960 Colonist expedition really believe the story?

One, at least, did. Some time after the news stories had appeared, he said, he’d been contacted by a Saskatchewan dentist. Years ago, the dentist told him, he’d known of a man on the Prairies who’d talked of a strange tunnel with steps carved into a mountain on Vancouver Island. From it he’d recovered several Chinese artifacts which he’d sold to a Victoria secondhand dealer. A check of old directories confirmed that, yes, there was such a dealer in Victoria at that time.

Which opens up a whole new realm of conjecture!

—Treasure Lost & Found in British Columbia; T.W. Paterson, Firgrove Publishing, 2018