The Ship That Came Back From the Grave

Part I

Honestly, folks, I don’t make this stuff up. I don’t have the imagination.

Take this story, for example:

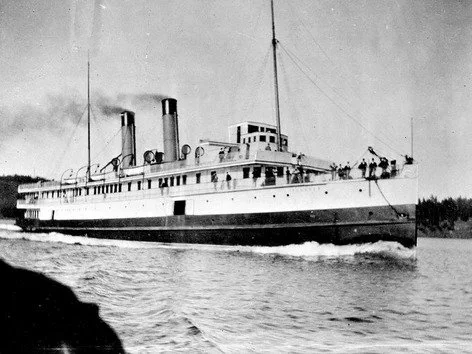

The former U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey ship Hassler achieved infamy as one of a rag-tag fleet of ships, sound and otherwise, that were pressed into service as passenger vessels during the hectic Klondike gold rush. —Wikipedia

“The Clara Nevada is probably America’s coldest cold case file. It is also the largest robbery in American history, twice the size of the Brink’s Job, and was the largest mass murder in American history until the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995...”

We’re talking about a 125-year-old shipwreck, not a bank heist!

I first wrote about the last voyage of the ill-fated Clara Nevada (as the Hassler was renamed upon being retired from government service) in the early 1970’s. That was for my second book. Shipwrecks had fascinated me since childhood but, back then, I had no idea that I’d barely scratched the surface of the Clara Nevada story...

It’s one of those rare stories that, rather than fade away, grow with the passage of time.

Let’s begin with my original telling:

* * * * *

GOLD! From the frozen wilderness of the Yukon came the magic word in 1897 that was to hold an eager world breathless for two exciting years. By liner, freighter, condemned hulk and homemade rowboat, 1000’s, from every corner of the globe, every walk of life, answered the siren call of untold riches.

Overland, from Skagway, Copper River, Ashcroft and Edmonton, it was by rail, stage, horse, oxen, dogcart, canoe, raft and on foot. Distance, hardship and death deterred few.

The resulting demand for shipping—of any size, description and state of seaworthiness—created the greatest marine transportation boom in Pacific Northwest history. Not since 1858 had British Columbia, Washington and Oregon seen such a rag-tag fleet of “ships” a-sail.

A crowded dock scene in Seattle which was repeated elsewhere as 1000’s of fortune seekers sought to find passage to the Klondike. Those who could afford it, sailed on sound and safe ships. Those who couldn’t, took their chances with almost anything afloat. Some, like the old Clara Nevada, were described as ‘floating coffins’.—Seattle Public Library

One of the motley hulks hastily pressed into service was the three-masted steamer Clara Nevada. Like many another member of the gold fleet, she was to suffer the supreme penalty of avarice. In fact, when we consider her age, condition and crew, it’s a little less than amazing that she ever cleared her Seattle berth!

First word of the loss of the Clara Nevada came via the Canadian Pacific Navigation Co.’s Victoria-based S.S. Islander which, three years later, also went down in Alaska’s notorious Lynn Canal. —Wikipeda

On Feb. 14, 1898, the crack Canadian Pacific Navigation Co. steamer Islander sent word from Union Bay B.C. that “the steamer Clara Nevada, which left Dyea and Skagway on Saturday afternoon, February 5, has so far failed to report to Juneau. As she was carrying several passengers from Skagway to Juneau, her not reaching there looks badly.

“Some steamer has met with disaster near Seward City, 50 miles north of Juneau. Some parties claim to have seen a steamer on fire and heard an explosion, and passengers say that the Clara Nevada was on fire on the trip up and had to have her boilers repaired.

“The beach near Seward City is strewn with wreckage, some of it painted in the same colouring as the Nevada. The wreckage was seen by Capt. Thomas Latham of the steamer Coleman, which arrived at Juneau from Skagway. The captain and crew all think it is the Nevada...

“There appears to be no question but that some boat has come to grief, and as the Nevada is the only boat not accounted for, it is thought to be her. All hands are supposed to be lost, about 40 people."

Built in 1872 as the Hassler for the US Geodetic Survey, the ill-fated steamer had been condemned after 26 years. But, with the sudden and exhaustible demand for ships, the newly-founded Pacific & Alaskan Transportation Co. purchased the aging steamer, renaming her Clara Nevada after a popular actress. Hastily outfitted to carry 200 passengers and 300 tons of freight, the Nevada entered upon her new service. It was to be deathly short.

After clearing Seattle with 200 passengers and crew, the Clara Nevada touched at Port Townsend and Fort Simpson, B.C., before reaching Skagway. It was upon her return voyage that she met with disaster.

When the first reports of her loss reached Seattle, her drowned company was soon forgotten in a riot of accusation, name-calling and slander which wasn’t to be forgotten—or forgiven—for many years after.

‘COFFIN SHIP... An unsafe, Ill-equipped craft with a drunken and blasphemous crew... A passenger tells of the many horrors of the Clara Nevada’s trip northward... Terrible tale by a man who for safety transferred to the Islander..." screamed the black headlines of the Seattle Daily Times, days later.

“The terrible story of the CN's wreck, with a loss of some 60 lives, grows worse as more light is thrown upon the vessel’s condition when she left Seattle,” the Times thundered. One hundred and fifty passengers and an immense value of valuable merchandise left this port in an unsafe vessel and in charge of a drunken and blasphemous crew over which a brave captain, a gentlemanly purser and a refined freight clerk sought to exercise the authority granted them by law.

“That she ever reached her destination is one of those modern miracles which God sometimes works in spite of man's failings, avarice, incompetence and greed.

“The whole story of that north-bound trip excels anything that has ever been told of a voyage on this Pacific Coast. It is a story that should bring the blush of shame upon the cheeks of the owners of that vessel, and that should bring the righteous indignation of an outraged public upon the heads of the culpable inspectors at this port.”

The story behind this devastating editorial broadside is as shocking today as it was to the Times readers of 125 years ago.

According to several passengers of that memorable voyage to the goldfields, the entire trip had been a comedy of errors which had escaped becoming tragedy only through, as the Times noted, a miracle.

“I was afraid that [she] would be wrecked from the time she left Seattle until Skagway was reached,” stormed Charles Jones of The Dalles, Ore. "We smashed into the U.S. Revenue cutter Grant when we were backing out from the Yesler dock; we rammed into almost every wharf at which we tried to land; we blew out three flues; we foundered around in rough water until all the passengers were scared almost to death. We witnessed intoxication among the officers, and heard them cursing each other until it was sickening.

While backing out from the Yesler wharf, shown here, the Clara Nevada “smashed into the U.S. Revenue cutter Grant. —Seattle Public Library

“It was an awful trip, and I would not have gone aboard that boat again under any circumstances."

Just four hours out of Seattle, alarmed passengers had circulated a petition requesting Custom officials at the next port-of-call, Port Townsend, detain the unlucky ship, that they might transfer to another, safer craft. A majority of those who hadn’t fled to the blind sanctuary of their cabins signed the documents, while Alaskan hotel keeper M.R. King, R.C. Smelzer and another passenger were appointed to a committee to plead their case with Customs.

Alas, that official replied, he didn’t have the authority to hold the boat; he took the names of the committee but when the petition was offered him he handed it back, saying that it would do no good, as he couldn’t act.

“Not 4 hours out of port and found in such a condition! Is there any excuse under high heaven that the inspectors at this port can offer for this state of affairs aboard the boat?” raged the Times.

The Nevada’s arrival at Port Townsend had further jarred frayed nerves when she rammed the wharf, “smashing our bowsprit, to say nothing of the damage done to the wharf. This made us still more anxious to hold the boat, but we were powerless and she got her papers."

Which leaves readers of today wondering which the frantic passengers valued more, their lives or the unused (and probably non-refundable) portions of their tickets?

Whichever, the terrified company remained with the ship, to experience misadventure after misadventure. Heavy seas near Fort Simpson strained the Nevada's ancient boilers, blowing out three flues. Twelve hours were spent in Simpson, making repairs. Continuing on—somehow—to Skagway, the ill-starred vessel made port safely, if not happily, as passengers scrambled down the gangway to again reach terra firma.

“She was not in charge of proper persons," Jones opined. "Two-thirds of them were drunk," the second mate was put in penance for 24 hours, commencing after we left Port Townsend.

Another crowded Seattle dock scene during the short-lived Klondike gold rush. At least, this ship looks respectable, if not overloaded. —Seattle Public Library

“The first mate was full the night we left Seattle. He drank all the time, but was yet able to be around and issue orders. The steward was drunk all the time. I never heard such language as was used by the waiters, mates and stewards. They abused each other shamefully, and made it very disagreeable for the passengers."

As for the engineers, he hadn’t “heard that [they] were drunk. [But] the freight clerk told me that the first engineer was taken on because he was a Mason, and not because he was a competent man. The freight clerk told me distinctly that as a matter of fact the engineer was incompetent.

“The captain, purser and freight clerk attended strictly the business and were gentleman.”

One of the petition committee, R.C. Smelzer, had originally planned returning upon the Nevada but, after the voyage north, changed his mind. When the hellship cleared Skagway, with some 63 passengers, “five or six of whom were women," one of those watching her departure was Mr. Smelzer.

As the old ship wheezed seaward, Smelzer recalled his last conversation with Capt. C.H. Lewis. The worried master “told me that if he ever got the Nevada back to Seattle and safety, she would never go out with him again unless she was in proper shape. He said her hull was all right, but that she needed new machinery. The captain claimed that when the Nevada was being remodelled and fitted, the owners would not listen to him, but did things to suit themselves.

“On one occasion, Capt. Lewis said that if he called on the engineer to back up he was sure to go ahead."

The scathing reports of Messrs. Jones and Smelzer which were "corroborated by 14 others," aroused indignation and anger throughout the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Adding to the litany of complaint, Second Steward Fred Emery, described the “hard trip up...the steamer acting like an old tub and the majority of the crew keeping drunk and fighting the greater part of the time, the rowdy element being so conspicuous that the steward, Dan O’Donnell would have been thrown overboard on the trip had not the captain had not the captain interfered."

Most newspapers, including the Victoria Colonist, echoed the bitter charges and counter-charges as the steamship Rustler continued rescue operations. She’d easily located the Nevada's grave, a reef off Eldred Rock in Lynn Canal (a 90-mile-long inlet on the south coast of Alaska, it’s one of the deepest fjords in North America).

Eldred Rock lighthouse in Lynn Canal. It was uncharted in 1898.—www.pinterest.com

The death ship lay in four fathoms, only her spars and lifeboats, tangled in the rigging, showing at low tide.

The Rustler’s search had been aided by reports of George Beck and his wife, of Seward City, who’d watch the small steamer “well out in the channel, at first bucking a headwind and afterwards breaking out in flames”. Days later, nearby beaches were littered with records, lifeboats and a fragment of the Nevada's name board, bearing three letters. Some debris was charred, while most showed no signs of fire. Heavy snow obscured any bodies and no survivors were found.

Inspection of the submerged hull by divers appeared to confirm that the theory of her destruction by the explosion of her boilers was correct, “the vessel being torn and twisted amidships so that her floating life after the explosion must have been limited to seconds, while the weather was too rough for the boats to avail anyone."

Inspiring salvage attempts were rumours that one party had been heading ‘outside’ with up to $120,000.

When the steamer Thistle docked in Victoria from Skagway, her officers reported that “Feelings run high at the Lynn Canal ports against the inspectors who permitted the Nevada to leave [Puget] Sound, incompetency of officers being freely charged, as well as that the boilers were leaking so badly when the ill-starred cruise was commenced that no firemen could work around them without being scalded.

“The matter is to be made the subject of a formal report, with a request that criminal proceedings be initiated."

Other rumours said Capt. Lewis had asked to be released from his command at Juneau but had been refused.

In Seattle, as shown, the disaster had prompted populist newspaper publisher Col. Alden J. Blethen, according to the respected H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, to brutally wield his SeattleTimes editorials against the Republican administration’s steamboat inspection service.

“....The wail of anguish that went up from the doomed throng aboard the boat that night and the sighs of grief that today break forth from the broken hearts of those whose loved ones were on the boat have found an echo in the hearts of all who have learned of this disaster, and in their and indignation they will not rest appeased until those responsible for this terrible crime have been brought to justice and adequately punished.

“Once more, the Times demands that the inspectors speak. You, Mr. [C.C.] Cherry and you, Mr. [W.J.] Bryant. You, who permitted the vessel to leave this port—what have you to say? The public want to know. The children, wives and mothers of those who were so suddenly ushered into eternity because you appear to have neglected your sworn duties want to know.

“Speak, men, speak, or else by your moody silence you admit that there is some foundation for the odious suspicions now hurled towards you by the public with whom you once swore to serve faithfully and well.

Have you fulfilled that oath?”

An opposition newspaper, the Post-Intelligencer, immediately leapt to the inspectors’ defence, quoting expert opinion that the boilers hadn’t exploded, as well as glowing testimonials of prominent marine men as to the character and competency of Nevada's officers and crew. In answer to the charge of drunkenness among the company, the Intelligencer stated the mishaps at Seattle and Port Townsend were the result of a broken engine room telegraph cable.

Probably the height—or depth—of the week-long SeattleTimes onslaught was the editorial that challenged Inspectors Cherry and Bryant to forward a defence like "decent criminals"!

The same account suggested a “fair trial” followed by the aforementioned officials decorat[ing] the end of an elevated rope!

Accusation and counter-charges had been so fast and furious that, today, it’s difficult if not impossible to learn the full truth. However, when all was said and done, it appeared the ancient Nevada had been sunk by explosion, although not that of her boilers.

A new theory, advanced by subsequent examination of the wreck, indicated she’d been wrecked when fire swept through her cargo of blasting powder, carried from Puget Sound “in defiance of regulations forbidding the handling of explosives by passenger steamers”.

(She was on her return voyage, remember, so it’s unlikely she’d have been carrying explosives south—but we’ll leave the fascinating forensics for next week.)

“The Stikine River Journal asserts that the hull of the lost vessel, now lying in 12 feet of water, shows little damage amidships where the boilers were placed, while the entire stern is gone, and the wreck is badly shattered aft, otherwise that it is certain the force of the explosion was here severest.

“This theory, it is pointed out, coincides perfectly with a description of the explosion by the people of Seward City, who said there was a crash, a great sheet of flame leaping skyward, and immediately after, all was clear.

The theory of fire, followed by an horrendous blast, was virtually confirmed when divers reported fire hose coupled to the ship's pumps had been laid along her sunken decks. But, whether her maligned boilers started the blaze remained a mystery.

Incredibly, the tragedy of the Clara Nevada was by no means ended. Readers of Washington's most entertaining nautical writer, Gordon Newell will be aware that, in his popular book SOS North Pacific, Newell recounted the eerie “death and resurrection” of the Nevada. It had been in 1908, he wrote, that yet another storm had swept Lynn Canal’s length and the lightkeeper of Elder Rock (built after the wreck of the Clara Nevada) had listened to the banshee wind with shook his perch high above the rocks and waves.

Renowned Pacific Northwest marine historian Gordon Newell, left, who told of the infamous Clara Nevada’s brief return from the grave. —saltwaterpeoplehistoricalsociety.blogspot.com

All that night the storm had blustered until, finally, the worst had passed and, with dawn, the lightkeeper had ventured outside. However, what began as a routine inspection of the island quickly became an exercise in horror. When he reached the rocky promontory’s northern tip, he’d been unable to believe his eyes.

There, driven high and dry by the gale, was been the shattered hulk of the accursed steamship Nevada!

Incredibly, the ghost was real enough, being complete with the ill-fated ship’s company, then no more than bones among the debris and marine growth...

Clara Nevada’s doomed company here the victims of the age in which they lived; the hectic day when dreams of finding raw gold drew men from every corner of the globe aboard, in anything that would float, forsaking comfort and safety in their mad rush to the diggings.

Considering the state of the majority of craft s into service, and the notoriety of British Columbia and Alaska shores, it can only be marvelled that most, if not all, didn’t meet with tragedy.

* * * * *

So I wrote, years ago. But there’s much more to the story of the tragic Clara Nevada. As you’ll see in next week’s Chronicles.