The Wreck of the S.S. Clarksdale Victory

Three-quarters of a century later, she’s still there—a rusted, broken hulk on the exposed, rockbound shore of Hippa Island, Haida Gwaii.

Looking like a broken toy in this aerial photo, S.S. Clarksdale Victory is still hard aground after three-quarters of a century. —Google Maps

The 80th of the Victory-class freighters that replaced the famous Second World War Emergency Shipbuilding Program’s Liberty ships, she’d survived the battle of Okinawa.

How ironic then that, come peacetime, while en route from Whittier, Alaska to Seattle, S.S. Clarksdale Victory crashed ashore in heavy seas off the coast of Graham Island on Nov. 24, 1947. Forty-nine of her 53-man crew perished.

* * * * *

The U.S. Navy transport ship Clarksdale Victory was almost new when she crashed ashore in November 1947. —Google Maps

British Columbia’s long and exposed Pacific coastline was a challenge and threat to navigators from the start. Indeed, the southwest shore of Vancouver Island was long known as the Pacific Graveyard, one stretch even achieving notoriety for “a wreck for every mile”.

Hundreds of vessels, from small fish boats to large freighters and passenger liners encountered grief along our shores, often with considerable loss of life. One of the worst of these West Coast maritime disasters which occurred within comparatively recent years, has been all but forgotten locally although it has been commemorated elsewhere.

This is the sinking of the United States Army transport Clarksdale Victory during the wild night of Nov. 24th 1947...

Fifty-two-foot high seas pounded the 7607-ton freighter running full speed down Graham Island’s rocky western shore, but Capt. Gerald R. Laugesen wasn’t worried. Balancing a mug of scalding black coffee in his hands, the 29-year veteran peered into the blustering darkness, trying to see beyond the towering seas that battered at his ship’s plummeting bow.

Suddenly, with a scream of twisting metal, the transport struck a reef, shuttered and held, throwing those on watch to the deck. Before they could regain their feet, the first breaker struck the ship in its giant fist, grinding her across the ragged rocks.

Graham Island, Haida Gwaii, is as exposed to the full violence of the Pacific Ocean as you can get. —Wikipedia

"Gale tears at transport rammed on B.C. reef,” dramatically announced the Victoria Colonist’s front-page headlines on a Tuesday morning. Victorians read of the grim struggle that had begun the previous night while they slept.

“Pounded by a 45 mile-and-hour gale, the US Army transport Clarksdale Victory is firmly aground on a reef and in serious trouble off the west coast of Graham Island in the Queen Charlotte group, 500 miles north of Victoria. No ship can reach the scene in less than 15 hours (approximately 1:00 p.m. today), it was reported at an early hour this morning,” the account continued.

"The Clarksdale Victory’s master sent out a general distress signal which was picked up at the Dominion Government Wireless station at Gordon Head at 9:58 p.m., immediately after striking the reef [while] en route from Whittier, Alaska, to Seattle.

“Rescue operations had already begun with the U.S. Coast Guard cutters Wachusett and Citrus hurrying southward from Alaskan ports. Citrus was expected to be first on the scene while, 17 steaming hours from tiny Hippa Island, where the Clarksdalle Victory had wrecked, the Alaska steamship company’s Denali was racing to her aid.

The first headline in the Vancouver Sun was a single column wide. Next day, the tragedy would take up much more of the Vancouver daily’s front page.

In the meantime, naval authorities at Esquimalt alerted the tug Heatherton at the northern Vancouver Island harbour of Port Hardy, and RCAF rescue planes awaited favourable weather conditions to take off from Sea Island. Also standing by was the Victoria-based tug, Salvage Chieftain.

Capt. Laugesen’s distress call had also been received by another U.S. Army transport, the General Omar Bundy, en route to Seattle with 2,000 troops from Yokohama. But Army officials quickly ordered her to continue to Seattle rather than enter the storm area with her many passengers.

—Vancouver Sun

The Dominion Weather Bureau continued issuing a gale warning for the mishap area, reporting winds up to 45 miles an hour. As help raced to her side, Clarksdale Victory rocked on mountainous breakers that swept in from 2000 miles at sea to hammer her 439-foot length unmercifully.

Then, on Wednesday, November 26th, newspaper headlines reported that the worst that occurred: Clarksdale Victory had broken up under the terrific pounding and there was no sign that any of her 53 crewman had survived.

The ship’s bow was still nosed up on the Hippa Island shore, but of the stern section and crew there wasn’t a trace.

Reported the Coast Guard: Two small search parties had landed on Hippa Island the previous evening and had found no survivors, despite earlier reports from a coast guard plane that it had sighted three men on the beach. Lieut.-Cdr, F.S. Scheiber, U.S. Coast Guard, told of the heroic landing in heavy seas, saying he and two others had landed in an amphibious plane, and a boat party had put ashore from the cutter Citrus.

Both groups had met and checked the island carefully but were forced to withdraw, disappointed.

—Vancouver Sun

Undaunted, Capt. Neils Haugen, commanding officer of the Ketchikan Coast Guard base, said the island would again be thoroughly searched as soon as possible. He reiterated that an aerial search had reported sighting three apparent survivors and said that supplies had been dropped. But he couldn’t account for the fact that the men hadn’t been found during Lieut.-Cdr. Scheiber’s inspection of the island.

Previously, Capt. Ben Aspen of the Seattle steamer Denali, first to reach the scene, had unsuccessfully tried to land on the windswept island. In fact, he almost lost several crewmen in his efforts.

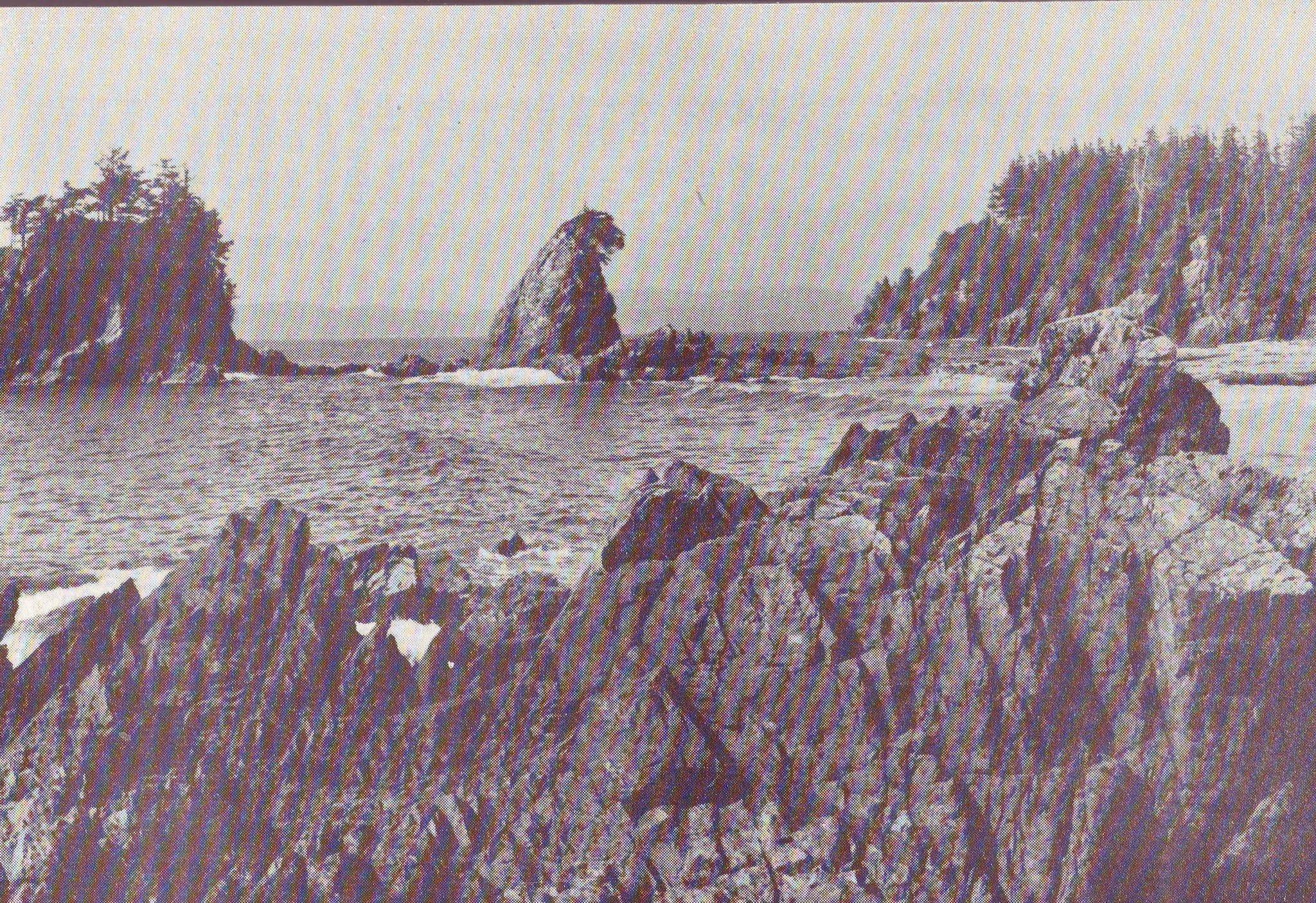

Typically rugged B.C. shoreline on a calm day. Now picture these jagged rocks during a raging gale with 50-foot-high waves (the height of a four-storey building) crashing ashore. —BC Government photo

Unable to make headway in the tempest, and afraid of being swamped, the party had returned to the ship. Suddenly, a giant wave splintered their little craft against the Denali's hull, dumping eight men into the sea. Fortunately, capable hands soon had them safely on board.

Viewing the Clarksdale Victory’s broken bow, a grotesque blur in the gloom, Capt. Aspen marvelled “how it would be possible for any person to survive”. He radioed that the ship was broken off by No. 3 hatch, and that no part of the bridge, midships or after-end was visible, terming " remarkable” the report that said three men had “got through the tremendous surf... Breakers are 50 feet high outside the wreckage."

Deciding against further rescue attempts, Capt. Aspen resumed his voyage to Seattle, but was ordered by his company to return to Hippa Island and “standby". Officials, despite Aspen's pessimism, drew hope from the sighting of a lifeboat and a life raft on the shore, saying that it wasn’t “likely that only three men could have survived in getting a cumbersome lifeboat safely ashore. Others might have taken shelter in adjacent woods."

The fact that the storm was abating strengthened hopes of soon learning the missing men’s fate.

It was reported that James A. Kaye, Clarksdale Victory's first officer, had survived three sinkings during the war and, after one, had drifted for many hours in a lifeboat in the frigid North Atlantic, off my Iceland, before being picked up by a destroyer.

Fifty-nine-year-old assistant engineer Tracy Lamoy, a veteran of 30 years at sea, had lived through a devastating boiler explosion that ripped another merchantman apart, years before. Said his wife, Antoinette: “My heart is always in my mouth on these dangerous trips."

Then the Coast Guard announced having rescued four of the Clarksdale Victory’s crew and having recovered four bodies.

The survivors, suffering from exposure, were Second Officer Henry H. Wolfe, Third Officers William M. Rasmussen and Claire Driscoll, all of California, and Ordinary Seaman Carlos M. Sanabria of La Ceiba, Honduras. Each had been washed ashore. Of the 46 officers and men still unaccounted for, authorities could but wonder.... and hope.

While search parties scoured Hippa Island, including the eastern shore of neighbouring Graham Island and boarded the freighter’s shattered bow, an intensive air search was begun for the missing after-section. At first it had been supposed that the stern sank immediately upon tearing loose, but now officials expressed the hope that it had simply drifted off with the lost crewman.

Twenty-two-year-old Carlos Sanabria, first to be rescued, had been rushed to the hospital, where he was treated for severe shock and exposure, a fractured rib, and painful bruises that covered most of his body. From his bed, the seamen described his last hour aboard Clarksdale Victory and his miraculous escape.

The transport, he said, was lifted bodily by a roller, striking heavily, and then shuddered. All hands were called to the boat deck to abandon ship, but because of the mountainous breakers it was thought safer to remain on board than to attempt to get off in the ship's boats.

“Ten minutes later, " his vivid, secondhand account continues, "The Vessel split in two at the Number three hatch. The section carrying the lifeboats and the crew slowly settled as the mountain of seas crashed heavily over the boat deck... The boats were carried away and in groups of two or three the crew was swept overboard into a maelstrom of churning water, wreckage, oil and rocks.

“The last I saw of Capt. Laugesen, he was climbing to the boat deck with about half the crew shortly before I was washed over the side. After about 20 minutes, I was washed ashore... I passed out until morning.”

Hope for the missing crew was abandoned when Second Officer Henry Wolfe said, “I think the others must have gone to the bottom with the stern. When the stern broke off, it went straight to seaward.”

Adding a touch of irony to the disaster was the surviving officer’s mention of the fact that Capt. Laugesen had been sure that they’d been at least 25 miles from land when the transport struck the reef...

The sinking of the Clarksdale Victory was the worst marine disaster of the northwestern Pacific coast since 1918 when the CPR coastal passenger liner Princess Sophia foundered with her hapless 100’s. Both ships ran hard around, bow-first, both had but time to radio for help before sinking stern-first, although the Clarksdale Victory left her jagged bow high and dry on the rocks.

Then, on December 3rd, newspaper headlines announced that the British freighter Sedgepool had run ashore on Provost Island, 40 miles north of Victoria. Gale warnings were in effect for that area, and readers waited apprehensively as the tug Salvage Chief sped northward to her rescue, many fearing that the Clarksdale Victory disaster was to be repeated so soon.

Fortunately, it was found that the Sedgepool had slid up over the rocks, rather than smashing into them, and she was pulled free 17 hours later. The worst damage inflicted was that to the crew’s morale—they’d hoped to be home for Christmas.

The public's attention turned to last-minute Christmas shopping while a search party continued to hunt for bodies and the Clarksdale Victory continued to disintegrate under the Pacific's relentless beating. When the official inquiry into her loss began later that month, even the newspapers seem to have lost interest.

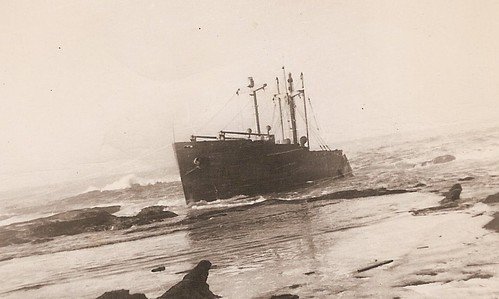

The forward half of the Clarksdale Victory as it appeared immediately after the storm. There was no sign of her stern section. Her rusted bow is still there on the beach at Hippa Island, a sad memento to one of B.C.’s worst maritime disasters.—www.Flicker.com

The year 1947 closed with relatives of crewman lost in the tragedy suing the U.S. government for damages totalling hundreds of thousands of dollars. Representing Mrs. Lorraine Ruth Dehne, whose husband was among the missing, was lawyer Melvin Belli. Fifteen years after, Belli would become famous for his defence of Jack Ruby, killer of accused presidential assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.

In March 1948, after several months of deliberation, a board of investigation found that when the transport grounded she was approximately 30 miles off course. That, as the vessel had been in ballast and the sea quite rough, her fathometer was next to useless.

One of the Clarksdale Victory’s lifeboats, washed ashore. —www/Flickr.com

That “the master of the Clarksdale Victory “committed a grave error in judgment and failing to lay a course which would permit him to pass sufficiently far off Cape St. James light with safety, taking into consideration unpredictable currents, unreliable radio direction finder fixes, lack of aids to navigation on the west coast of Graham Island and the Queen Charlotte group, and weather conditions which would prevent obtaining celestial observations."

That, finally, the principal cause of her loss was the “accelerated and unpredictable easterly ocean currents which were not present on the northbound voyage to Whittier."

The Clarksville Victory hadn’t been equipped with radar.