They Called Them ‘Hell Ships’ For Good Reason

Google the term ‘hell ship’ and you’ll find that it has come to be applied to the Japanese transport of American and Allied prisoners-of-war for slave labour in the home islands during the last two years of the Second World War.

But the term goes back much longer than the mid-1940s.

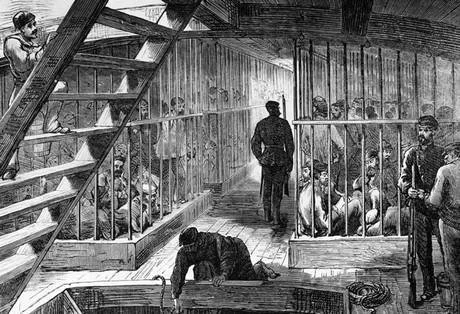

All the way back to the American Revolution, in 1776, in fact, when the British rather than the Japanese were the villains. Old ships’ hulks, no longer seaworthy, made cheap and easy to guard floating jails for prisoners-of-war in America and for convicted criminals in the Mother Country.

This prison ship is transporting British felons to Australia when stealing a loaf of bread to survive could earn you deportation for life.—www.Pinterest.com

But, between the 1760s and right up into the 20th century, ‘Hell Ship’ was a term used time and again in newspapers of the Pacific Northwest in reference to ships whose masters and mates brutalized their crews.

This was when it was accepted internationally that a ship’s captain was little short of God.

He was to be obeyed, instantly and without question—period. Some masters, a minority, happily, ran not only a ‘tight’ ship but became notorious for enforcing their orders with anything that came to hand—a belaying pin, brass knuckles, a whip, even a gun.

Upon such aptly-named hell ships reaching port, Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle and San Francisco newspapers reported harrowing tales of shipboard brutality that sometimes made it to a courtroom where the odds and the law favoured the accused master or mates.

As if going to sea before the mast wasn’t life-challenging enough, to find yourself in effect a captive aboard a ship with a sadistic master or mate with no chance of relief or escape must indeed have been hell afloat.

* * * * *

“Altogether he is the worst sight that has been seen in the hospital here for some time, and if he recovers it will be a miracle.”

It was, in the purplish prose of the Victoria Standard, “a most unparalleled instance of human cruelty on the high seas”.

As noted, the records show that the officers of the ship Detroit were anything but unique in their allegedly brutish mistreatment of their crew. In that age of wooden ships and iron men, when maritime laws recognized a ship's captain as having supreme power at sea, the Detroit and others of her ilk were known as 'hell ships' for the maltreatment of their crews.

Upon her arrival in Victoria from Valparaiso, one of her seamen charged before the U.S. Consul that he'd been denied proper food until he was “literally eaten up with scurvy,” and that he'd been whipped with a rope's end, by the captain's orders, for not being able to perform his duties. His legs were said to be blackened by bruising from the thighs down, his teeth ready to drop out, “and altogether he is the worst sight that has been seen in the hospital here for some time, and if he recovers it will be a miracle”.

According to this complainant, just days before arriving in port, Capt. J.C. Adams had kicked a seaman to death and thrown his body overboard.

It's little wonder that Nanaimo citizens were intrigued by the maligned Detroit's subsequent arrival at Departure Bay to load coal, notwithstanding the fact that not only the ship's officers but several of its seamen had sworn that the charges made in Victoria were “a tissue of falsehoods”. While being examined by Consul Francis the crew defended their captain, although they damned the first and second mates for what they termed “extreme cruelty”. They told the same story to Collector of Customs T.E. Peck.

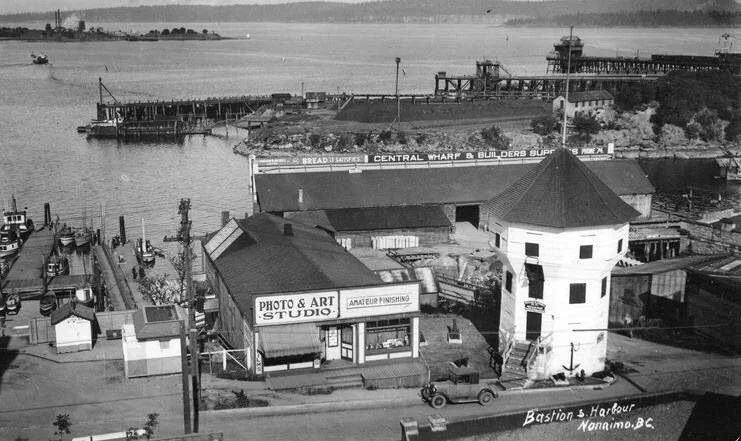

Coal port Nanaimo. —www.Pinterest.com

As for the seaman allegedly kicked to death and thrown overboard, his body had in fact been brought ashore for burial. Because of the serious accusations being floated about, Dr. Jackson, formerly of the Royal Hospital, was asked to perform a post mortem. He issued a certificate of death by natural causes.

Despite this conflict of evidence and testimony, with the possibility that criminal charges might be laid against the Detroit's officers, the Nanaimo Free Press reminded its readers to reserve judgment until they were fully informed of the facts.

The collier's first and second mates chose to ignore the newspaper's advice by jumping ship during the night and making good their escape in one of its boats. By this time the Press, which had been non-committal, had had time to interview some of the crew. It now suggested that “matters were getting too warm” for the missing officers, that it was because they dreaded British justice that they'd jumped ship for parts unknown.

“Judging from the conversation of some of the crew, it would appear that they have had a rough time of it, and been terribly ill-treated by the first and second officers... One of the two officers was in the habit of carrying a heavy sling shot [sic] attached to his wrists.”

As for withholding judgment until the case could be tried in court, the newspaper concluded, “He confesses his guilt who flees from judgment.”

Days later, a legal notice appeared in the Press. Signed by Capt. Adams, it stated that neither the owners nor the undersigned master of the American ship Detroit would be responsible for any debts contracted by the crew thereof.

Soon after the Detroit took her leave of Departure Bay, her holds a-brim with Wellington coal, Capt. Adams had bigger concerns than unauthorized expenses. In its last reference to the sordid affair, the Press reported that he'd been placed under a bond of $1000 to appear before a court in San Francisco.

He'd been ordered to answer a charge of cruelty for having allowed his officers to “beat and wound a seaman during the voyage of the ship from Rio de Janeiro” to the Bay City.

* * * * *

“Like a thief in the night or sheep-killing dog...’

How’s that for a newspaper headline?

So wrote the Victoria Colonist of the schooner Hera’s arrival in Seattle in October 1896.

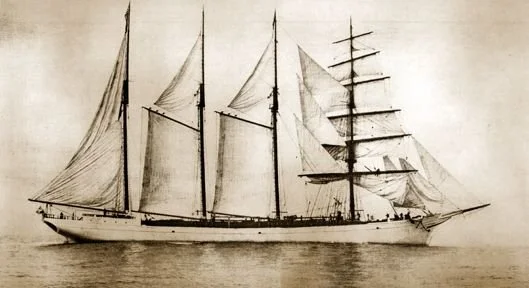

The four-masted schooner Hera.made newspaper headlines upon her arrival from Nome. —www.Pinterest.com

The details of the news story are even more chilling: “Dead, dying, crazed and crazy, weak, tottering and famishing, is the story told of the nearly 200 passengers of the schooner Hera which has arrived from Cape Nome this morning.

Like a thief in the night or a sheep-killing dog afraid to face the light of day with honest men looking on, the piratical-looking craft crept past the city silently and without noise, and cast her anchor in the upper bay, close in against the foul-smelling old fertilizer factory...”

What had the Hera done to warrant such a scathing welcome?

The schooner brought with her an incredible tale of suffering and death that outraged the entire Pacific Northwest, a story almost unbelievable but all too true...

The Blue Star Line’s ancient workhorse had sailed form Nome a month before, Seattle-bound with 200 passengers. For $50 each the unsuspecting prospectors returning from the Klondike had been assured “the grub was all right, plenty of it, and wholesome and good”. Accommodation would be “rough” but, otherwise, “everything would be prefect”.

But instead of an uneventful passage or at worst one marred by the odd storm, the unhappy ship’s company endured privation and hardship. For two of the Hera’s 100s, the voyage home was their last.

The schooner was not long at sea when the food began to run low.

Then began a month that defies comprehension, today. Just two days out of port, meat (salt horse “of a very poor quality” and canned mutton), sugar and butter ‘disappeared from the bill of fare” and the ship’s entire supply of fruit provided only three courses of dried peaches and two of prunes. Potatoes, passengers grumbled, weren’t to be seen throughout the voyage.

“The only thing there seemed to be plenty of was flour,” sneered the Colonist. “The ship never ran out of that, and the last four days the bill of fare was bread made from sourdough, coffee and water. Even the latter had been in short supply, it being stated that only providence in the form of rain showers had spared the Hera’s famished passengers from running out of that vital fluid.”

Twenty-four days out of Nome (24 days en route from Nome to Seattle!—Ed.), Sacramento passenger J.S. Ryan succumbed to what was said to be malnutrition.

He’d been “well to all appearances, and was on his feet up to two days before he died. The overcrowding aboard, ill ventilation, lack of necessities, forced exposure soon brought on a crisis which carried him off...”

Forced to fend for himself (the newspaper didn’t question why the other passengers didn’t do more to save him), Ryan had become steadily weaker, at one point wandering onto the windswept deck in his bare feet. Hours later, he died.

His body was committed to the deep by a nine-man cortege that was itself was almost swept away by the stormy seas during the brief ceremony.

Ryan’s death by alleged starvation and what appears to have been medical neglect was the fault of the Hera’s officers, charged G.A. Wiseman, whom the Colonist described as “an intelligent man from San Francisco”. Worse yet, Ryan wasn’t the only passenger to die during the ill-starred voyage.

When Hera went on to Puget Sound the Seattle Daily Times told of George Lamby: “The story of one was the story of the other [Ryan].

“None to look after them, becoming weak from lack of nourishing food, then the almost total lack of medicine, and absence of all food suitable to the sick, soon developed into typhoid fever, which was not long in doing its worst.”

Poor Lamby had suffered misfortune from the start of the voyage, having been robbed of his $400 stake just before sailing.

By the time Hera limped to within 50 miles of Cape Flattery, the passengers were down to sourdough bread and weak coffee—until the water supply which had been supplemented by rain showers, also began to run out.

While becalmed, she was able to report her critical condition to the passing vessel Lakme whose master immediately headed to port to seek aid. Hours later, smoke on the horizon heralded the arrival of the Coast Guard cutter Grant and the tug Sea Lion. Once the former had determined the schooner’s exact situation, she pulled aside to allow the tug to go to work.

Sea Lion brought the Hera’s beleaguered company more than a towline—food!

Meat, potatoes and sundry supplies were dumped onto the schooner’s deck then the tug secured a line and began the 24-hour-long haul to Seattle. Of the 200 prospectors who’d joyfully stomped aboard in Nome, bound for the “Outside” a month before, few were in condition to immediately begin to enjoy their wealth from the Klondike gold fields, some being too weak even to carry their dust ashore.

* * * * *

When next the infamous Hera made headlines, three years later in November 1899, it was to report her shipwreck. Laden with a cargo of lime she’d been battered by a storm that opened her ancient seams, enabling the sea to ignite the lime in her holds.

Compounding her misery was the fact that she was in the world-notorious Graveyard of the Pacific.

For 24 hours her frightened crew fought to keep her afloat as fire smouldered below her decks and she was driven ever closer to the jagged shore. Upon drifting into Clayoquoat Sound, Capt. Warren dropped anchor then, with two passengers and two crewmen, launched the ship’s boat and rowed desperately for shore through towering waves. Although threatened with capsizing they were able to land safely and a rescue team of Clayoquot settlers set out to rescue her 13 remaining seamen.

Then began Hera’s legend as a phantom ship. With flames soaring skyward and no pilot at her helm, she drifted through the rock-studded channel between Stubbs Island and Tofino before finally nudging the beach and burning to the waterline. In 2007 her submerged remains were declared an official underwater heritage site, marked by a plaque.

It makes no reference to her ‘hell ship’ voyage from Nome in 1896.

* * * * *

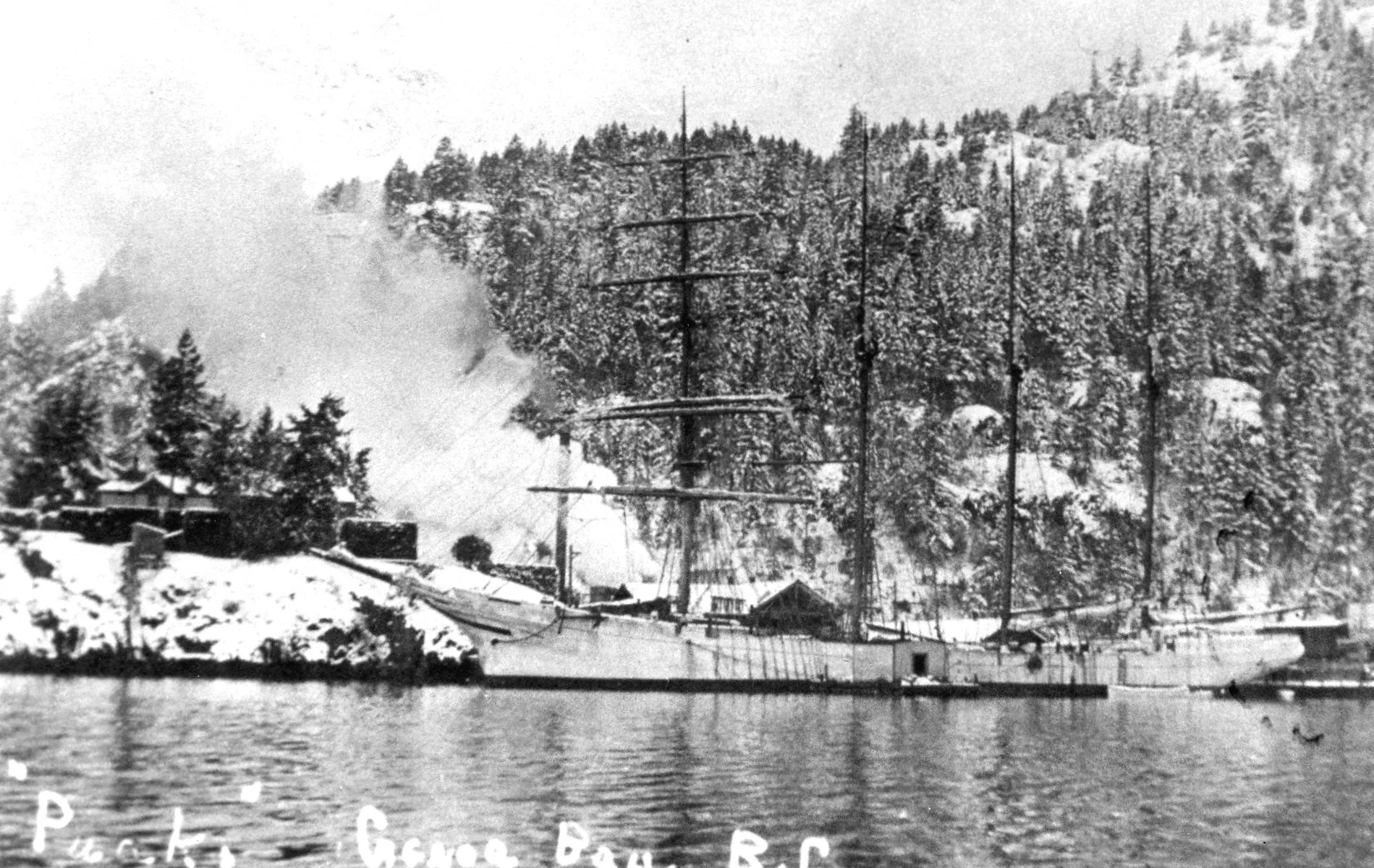

The beautiful but infamous sugar ship, Puako. —www.Pinterest.com

We’re coming close to home with the story of this hell ship, the Puako having been a frequent visitor to Chemainus and Genoa Bay where she loaded lumber. A 1940s American historical source gives her particulars accordingly:

“The Puako, a four-masted barkentine of 1084 tons and 1400 M capacity, was built at Oakland [Calif.] by W. A. Boole & Son in 1902, [was] another of the skysail yarders operated by Hind, Rolph & Co. She was laid up at Victoria in May, 1921, and in 1926 was sold to the Pacific Navigation Co., Vancouver, and converted to a log-barge under the name of Drumwall.

“She is now owned as a sawdust barge by the Island Tug & Barge Company. Victoria. —John Lyman, "Pacific Coast Built Sailers, 1850-1905," The Marine Digest. July 26, 1941, p. 2.”

Here’s the story of the Puako as I wrote it in Cowichan Chronicles, Vol. 1.

He signed himself as Adolph Pedersen, master of the good ship Puako. Seamen knew him as ‘Hell Fire’--as nasty a captain as ever stalked a holystoned deck. His local connection is brief—but fascinating!

“...He was a mild appearing character, looking a little as if he’d just stepped from the pages of a story by W.W. Jacobs,” wrote the late Cecil Clark, former deputy commissioner of the B.C. Provincial Police, in 1959. “Although it’s 41 years ago, I remember he had on a well-worn ‘Christy stiff’ hat, a little high in the crown, a blue serge suit that shone a little at the elbows and seat, and around his throat I think he wore a muffler, perhaps to hide the lack of a collar. He spoke in a quiet tone, almost apologetically.”

The reason for Pedersen’s visit to police had been to report that three of his crewmen had jumped ship. The reason for Clark’s startling recall was the fact that, when next he heard of Pedersen, the Puakao’s diminutive master, he’d been charged with murder on the high seas.

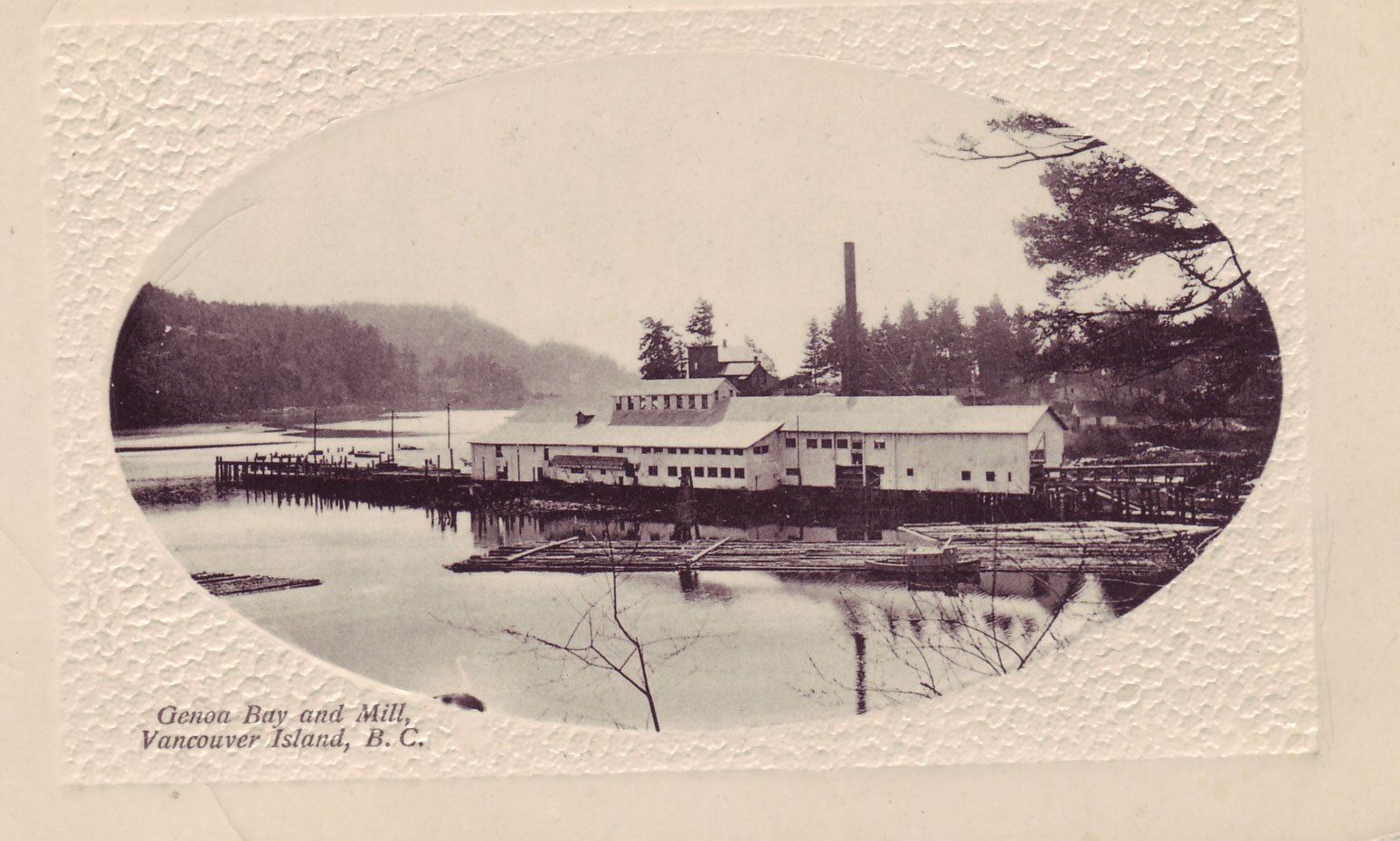

The Cameron mill where the infamous Puako loaded lumber in 1917. —Author’s Collection

Victorian Fred Sherman had reason to remember Pedersen, too. In February 1917, 18-year-old Sherman operated a water taxi for Cameron Lumber Co.’s Genoa Bay sawmill. It was in this capacity that he met the seagoing terror known as ‘Hell Fire.’

As boat operator, it had been Sherman’s duty to shuttle mail, supplies and passengers as occasion demanded. When the sleek brigantine Puako (one of history’s cruel jokes, it means ‘flower of the sugar cane’) warped alongside the Cameron Mill to load lumber, Capt. Pedersen needed a ride. He was leaving for San Francisco to meet his wife.

He’d already piqued young Sherman’s curiosity on two counts.

Firstly, “He sure made lots of noise for such a little fellow!” As the Puako was towed towards the Genoa Bay mill, “I could hear him shouting orders, way down the harbour.”

The second thing to twig Sherman’s attention was his physical appearance. Although his name suggested Scandinavian origins, he “look[ed] more like a Mexican than anything else. He was a little, short, chunky fellow.”

Once he’d escorted Pedersen to Cowichan Bay, Sherman returned to the ship to make the acquaintance of Pedersen’s two sons, “fool[ing] around with them in my spare time. We’d take a .22 and an outboard around the harbour, hunting ducks. They were about 14 and 16, or a little under. They were short and stocky, like him, so didn’t look as old as they might have been.”

Mr. Sherman found the young Pedersens to be quite agreeable during their Cowichan sojourn. By this time he’d heard rumours about Pedersen Sr. The sons enlightened him. Once, they shrugged, the old man had left two seamen to die in a paint locker during a shipboard fire.

Even her name. Puako–‘Flower of the sugar cane’–was a cruel joke.

“They said the men had been burned up, I remember that,” he recalled with a shudder.

Upon Pedersen’s return, with his wife, the young boatman caught a chilling glimpse of the sea captain who, once on the high seas, became ‘Hell Fire.’

After taxiing them to the ship, Sherman carried their luggage to the saloon, where Pedersen barked, “Where’s my laundry!”

“I don’t know, I’m not your laundryman!” Mr. Sherman retorted.

Pedersen, eyes flashing fire, advanced on the startled youth. “He looked at me just as if he was ready to keelhaul me. If we’d been deep sea, that would have been the last of me. I’d have been over the rail.”

“In fact, I’d have been dead on the way over, too!”

Puako finally cleared Genoa Bay, her holds and decks crowded with 1½ million feet of lumber, for Cape Town, three months’ distant. As her crewmen later testified in court, those three months were an eternity.

The Pedersens, you see, ran a tight ship. If an order failed to inspire instant response, a swift kick or blackened eye did. Because experienced seamen were scarce during the First World War, the punching Pedersens made do with what they had, a motley mix of backgrounds and nationalities.

Danish seaman Oscar Hansen urged his shipmates to stand firm. The cook even sprinkled ground glass in Hell Fire’s breakfast. But Pedersen’s grinding false teeth saved him.

For weeks the father and son team delighted in reducing the cook to little more than a shambling bruise with their flying fists and heavy-toed boots. Finally, in mid-Atlantic, while fleeing from yet another beating, the stunned cook tumbled overboard.

First mate Leonard held the Puako on course, leaving him to drown.

Then they turned to the rebellious Hansen. After repeated beatings he was handcuffed, leg-ironed and locked in a small oil and paint locker. A week later the semi-conscious Dane was hauled on deck and brass-knuckled before his cowed shipmates.

Hansen retreated aft as young Adolph hit him again and again until, trapped against the railing, Hansen leapt over the side and clung to the logline (the ship’s ‘speedometer’). He couldn’t hold on for long, of course, as Adolph Sr. forsook him without so much as a backward glance.

Upon Puako’s eventual arrival in New York, the surviving crew had the Pedersens charged with murder. But a court accepted their plea that neither victim could be rescued as the ship couldn’t put about quickly enough.

Half a century after his Cowichan Bay encounter with the fiendish Pedersens, Fred Sherman could laugh at his escape from ‘Hell Fire’:

“It was just good luck, is all. I’ve often thought about it. I just happened to be in the right place when I talked back to ‘Hell Fire’ Pedersen.”

* * * * *

There were other masters and other voyages before Puako ended her career in a Vancouver Island breakwater. This photo shows the wife of Capt. Charles Emil Helms and her dog aboard while the barkentine was moored in the Fraser River in 1919. —Free Domain from the collection of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

The Crown Zellerbach breakwater at Royston, V.I. is the home to a score of historic sailing and steam ships, among them the ill-starred barkentine Puako which ended her days as a barge, the Drumwall, and towed about by a tugboat. —Author’s Collection

The Detroit, Hera and Puako were just three of the ships of old that earned eternal infamy as Hell Ships.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.