This Phoenix Didn’t Rise From the Ashes

Part 1

This was no Wild West town of false-front buildings lining a single street and a scattering of shacks. The Boundary Country’s Phoenix was nothing less than a city in every sense of the word: modern substantial buildings and services, fine homes, a hospital, even a skating rink, and not one but two rail connections to the outside world—all the latest amenities of the first two decades of the 20th century.

Then—“the highest incorporated city in Canada” was gone, just a man-made lake on top of a mountain in the wilderness.

Phoenix, B.C. —BC Archives

In a single generation the Phoenix mines had yielded an amazing $100 million ($2.5 billion today) in copper, gold and silver ores. But Phoenix was a company town, dependent upon a one-horse economy that spelled riches for its owners and jobs for its workers—both its genesis and nemesis—and all within just a few years.

British Columbia has seen 100s of ‘ghost towns’ over the past century-plus but there never was another like Phoenix.

* * * * *

With the coming of the railway the great mining boom was on. As production soared, so did Phoenix. From an area of just two square miles, in a single generation, the Phoenix mines, for several years at least, shipped more copper ore than all other mining camps of Canada combined!

“It was a camp whose principal mine was opened by a man [virtually] broke, but in a few years paid $10 million in dividends; a camp that...started professional hockey in the province, where $1,000 bets on games were not uncommon; and the camp which originated skiing in British Columbia...”

The pioneer “camp” of these impressive distinctions was Phoenix, in its day the “highest incorporated city in Canada”. Like its legendary namesake, it flourished and died—not in flames, to be reborn anew, but a victim of cold business logic.

For a time, it appeared that Phoenix would live up to its name and boom again. But this dream of resurrection never did occur and the former mining camp is now but a memory to its former residents’ descendants and provincial lore.

Situated in the Boundary District of British Columbia, about 20 miles north of the international border, Phoenix, at an elevation of 4500 feet, overshadowed, in fact and in production, it's nearest neighbours, Midway, Greenwood and Grand Forks.

Although built upon a mountain of copper, it was the eternal search for gold that led to its founding, late in the 1880s. After the placer strikes in the Fraser River and Cariboo, prospectors had looked farther to the east, pouring into the Boundary Country from the west and from Washington by way of the Dewdney Trail. The first placer strikes were made on Boundary and Rock creeks; when these played out, lode deposits were discovered at Midway and Greenwood.

During this period the miners had noticed that gold was greatly surpassed in quantity by deposits of copper. Copper, however, unlike its yellow and more precious cousin, required large-scale production. This in turn required an efficient and economical transportation system and, at that time, there was no railway.

In July 1891, Matthew Potter and Henry White staked the Old Ironsides and Knob Hill gold claims. James Schofield and James Atwood located the Stemwinder, and Joe Taylor and S. Mangott staked the Brooklyn property. Three years later, John Stevens located the Victoria claim. In the meantime, the Silver King property, which adjoined the Old Ironsides property, had been allowed to lapse. Relocated by Robert Denzler, who named it the Phoenix, it and the other three claims were the first of 100s of properties to be staked in the immediate vicinity.

But the Old Ironsides, Knob Hill, Victoria and Phoenix properties—when mined for copper—proved to be the richest of them all and the foundation—literally—on which the bustling town of Phoenix was built.

The shift in emphasis from gold to copper came about with the construction of the Spokane Falls and Northern Railroad. Although this new line ended at Marcus, Washington, a full 60 miles to the southeast, it made the mining of copper far more appealing to speculators and attracted development.

In the meantime, work on the original four claims had required considerable capital and control of all four had been assumed by J.P. Graves and Al White of Spokane who in turn sought further financing. This, they received from the aptly named S.H.C. Miner, president of the Granby Rubber Company of Granby, Quebec. With the money advanced by Miner’s business associates in Eastern Canada, the Miner-Grave Syndicate reorganized in 1899 to become the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company Limited.

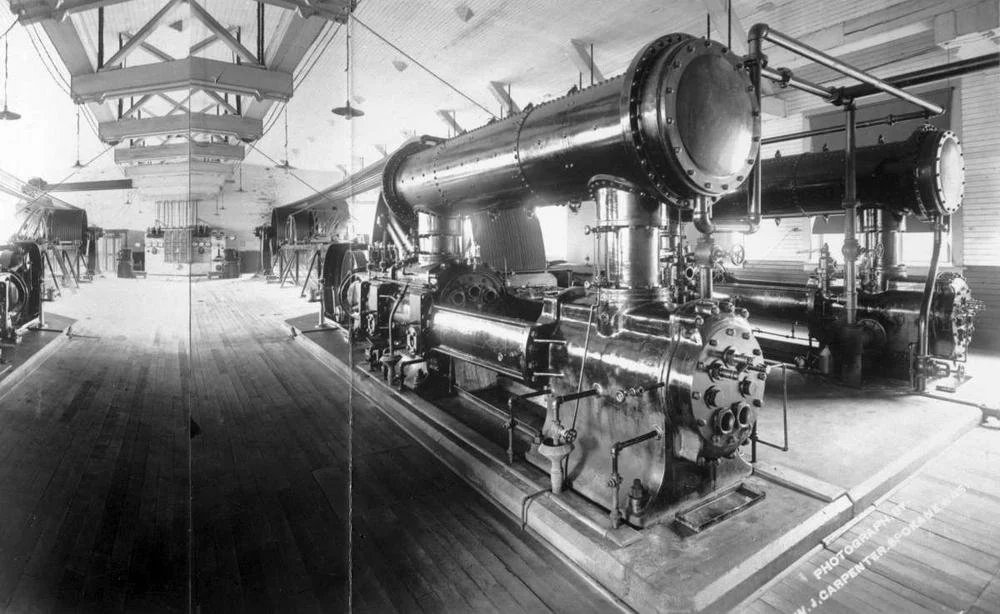

(Top) As noted, copper mining required costly investment, as shown by this Granby Company compressor room for just one of its properties.

(Bottom) The men who ran the massive operation, the managers of the Granby Mining, Smelting and Power Company. —BC Archives

Such massive financing had been required by the fact that mining in this region was by the “square-set” method, meaning that all excavation had to be done by tunnel. These required massive amounts of timbering, as demonstrated by the fact that, in 1902, one Phoenix worker in 10 was a ‘timberman’. Fortunately, the area was well provided with pine and tamarack, and the logs for the 1000s of 10x12-inch timbers were readily available.

This left the expensive matter of a railway.

As crews of miners blasted away underground and built up extensive stockpiles of copper ore, the Canadian Pacific Railway linked Phoenix and Greenwood with a 25-mile-long right-of-way. On May 21, 1900, the last spike was driven in the spur to the Old Ironsides Mine’s bunkers. Reported the Greenwood Times: ‘Amid the shrieking of steam whistles and the cheers of assembled miners and other citizens of Phoenix, and with the ore bunkers gaily decorated with flags, the last piece of steel was laid to the Old Ironsides’ ore bins at noon today.

“Immediately after the last spike was driven the deep basso profundo whistle of the Ironsides shaft heralded the welcome news, quickly followed by the Knob Hill, and in turn taken up by the War Eagle, Gold Drop, Golden Crown and other mines. The terrible, ear-splitting din was not lessened by numerous explosions of dynamite and CPR locomotive whistles.

“The citizens of Phoenix sent 10 barrels of Phoenix beer to the workmen immediately after completion. This marks a new era here and its effect is already being felt, about 14 lots having been sold in the three town sites in the last two weeks.”

Almost immediately, smelters were completed at Grand Forks, Greenwood and Boundary Falls, and the great boom was on. As the mines boomed, so did the town of Phoenix, which sprang up immediately adjacent to the Knob Hill and Old Ironsides mines as the owners of the Cimeron, Phoenix and New York claims also surveyed and sold their surplus land for residential and commercial development.

The Granby Company was famous for never doing any things by halves—this substantial building is its employee boarding house. —BCA

By this time, noted Midway writer Susan Hillard, “The ladies of Phoenix were delicately holding up their skirts as they crossed from boardwalk to boardwalk on dusty Old Ironsides Avenue. Phoenix stage-lines MacIntyre and Macdonald, proprietors, made two daily round trips from Greenwood to Phoenix, and visitors to Phoenix might choose from a variety of hotel accommodation.

“Finest Wines, Liquor and Cigars’ were offered at the Brooklyn (the town’s leading hotel), at the Bellevue, the Mint, the Union, the Imperial (table board $7 a week), at the Morden, the Golden, Kings, Queens and Victoria House. By September 1900, the city's newspaper, the Phoenix Pioneer, was appearing weekly, and in its mining articles, social notes and in advertisements it struck a note of exuberant optimism...”

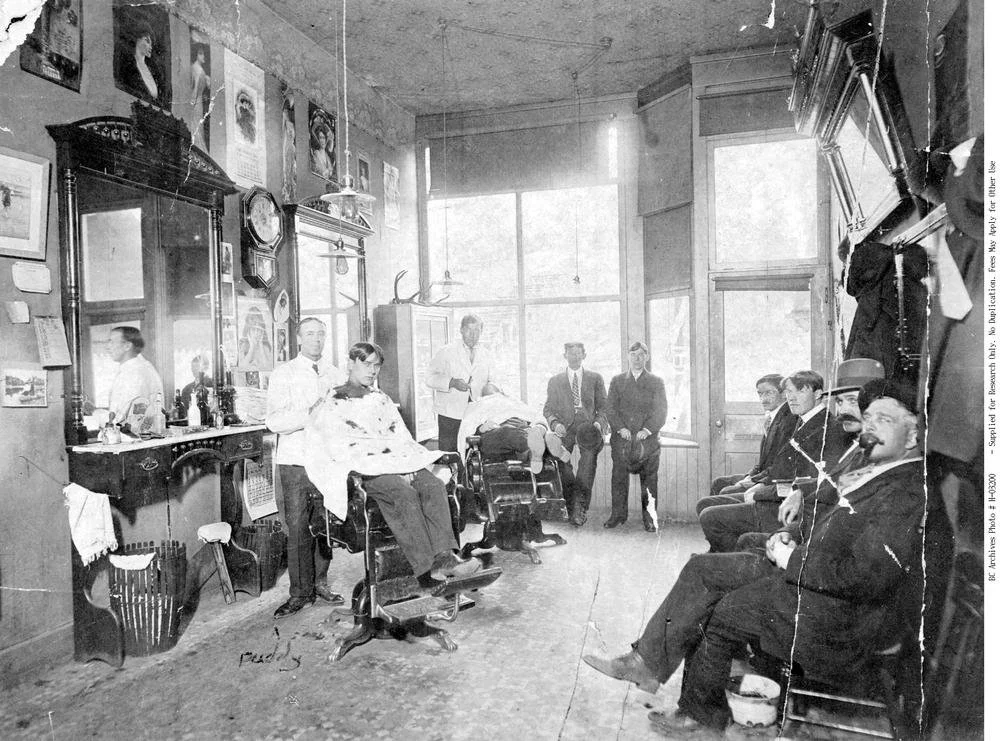

A wonderful photo of L.R. Purdy’s barbershop. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall as Purdy and his patrons shared the latest mining news and social gossip on the B.C. frontier... —BC Archives

Besides hotels and saloons, Phoenix had a small respectable side as well, with four churches—Congregational, Presbyterian, Anglican and Roman Catholic—a hospital and school. The three-storey Miners Union hall boasted a theatre, banquet hall and “the finest ballroom in the interior of the province”. There were also the usual business establishments and services, a brewery, shops and a covered skating and curling rink.

In short, Phoenix was nothing like the usual fly-by-night mining camp, but a substantial community with fine buildings of brick and wood. By the fall of 1900, George Rumberger, the town's first mayor, and the man who had given it his name, in honour of Denzler's claim, enthusiastically described the production of the leading mines and expressed his faith in the future of Phoenix in the Pioneer.

As further proof that Phoenix was not the usual rough-and-tumble mining camp of the B.C. frontier, its public school. —BC Archives

At that time, he said, the various mines were shipping a total of 3500 tons of gold and copper or per week, of which the Knob Hill and Old Ironsides mines contributed 300 tons daily, and the B.C. Mine, 150 tons per day: “The shipments from Phoenix alone far exceed the combined output of all other mining camps in B.C., outside of Rossland,” gushed Rumberger. “Yet Phoenix is only in its earliest infancy.”

While the Granby Company was the undisputed leader, with its Old Ironsides, Knob Hill, Curlew, Snowshoe and Gold Drop mines, there was also the Dominion Copper Company, owners of the Brooklyn, Stemwinder and Idaho mines; the Rawhide and Athelstan mines were operated by the British Columbia Copper Company. As all ore had to be loaded into cars capable of holding a ton each, hauled to the hoist house, then caged, hoisted and taken to the bins for dumping, there was keen rivalry between mines and crews to see who could load the most ore in an eight-hour shift.

Average tonnage hauled to the surface in a 24-hour period seems to have been 500 tons although one shift produced an amazing 18,000 tons in a single month, at the rate of 600 tons per day.

As production soared, the tunnels of the original Granby properties were linked underground and the horses used to the ore cars to the base of each shaft were superseded by the more efficient electric motor. Progress had also meant the layoffs of many of the timbermen, it having been discovered that some of the later workings did not require the excessive amounts of timbering.

Miles of tunnels beneath the buildings and streets of downtown Phoenix could lead to cave-ins such as this one. —BC Archives

This development, according to Mrs. L.M. Haggen, MLA, in an address to the British Columbia Historical Society in 1957, was welcomed by the company timekeeper, who, until that time, had to devote long hours to keeping the timbering accounts straight.

In July 1900, noted Mrs. Haggin, the CPR reached Phoenix and the first ore train made the 25-mile-long downhill haul to the smelter at Grand Forks. Because of the steep grade, the CPR used a Shay locomotive which, although slow, could pull twice the number of cars of a regular locomotive as every wheel on the engine and tender were drive wheels. Nevertheless, the CPR experienced its share of difficulty on this stretch of track.

On one occasion, Mrs. Haggen recounted, “a shay engine and 24 cars ran away, jumped the track, and everything was smashed to pieces.

“The track was so littered that, instead of clearing away the debris to keep the ore moving, the company built a temporary detour track. Another train which ran away sailed merrily down the mountain till it came to a level spot and just simply stopped, with no damage done. A few years later, the Great Northern built into Phoenix and for nearly 20 years two railways night and day getting ore from Phoenix to the smelter.”

A wrecked Phoenix ore train, although this is not the Shay locomotive mentioned by Ms. Haggin. Other photos suggest that train wrecks weren’t all that uncommon in the steep country that surrounded mountaintop Phoenix. —BC Archives

By 1905, no fewer than 26 mining companies were in operation, as well as the smelters at Grand Forks, Greenwood and Boundary Falls, making the Boundary District one of the busiest in the country. Beneath the city of Phoenix, 50 miles of track were interconnected in a giant maze and employed 1500 miners.

When not on shift, many of the men spent their time in one of the city’s 17 saloons, all of which were open around the clock, where they indulged themselves in drinking and gambling; joined one of the 16 secret lodges; skied or curled. Hockey games, particularly those between the Phoenix team and their arch-rivals from Grand Forks, drew such capacity crowds that special excursion trains had to be run between the communities.

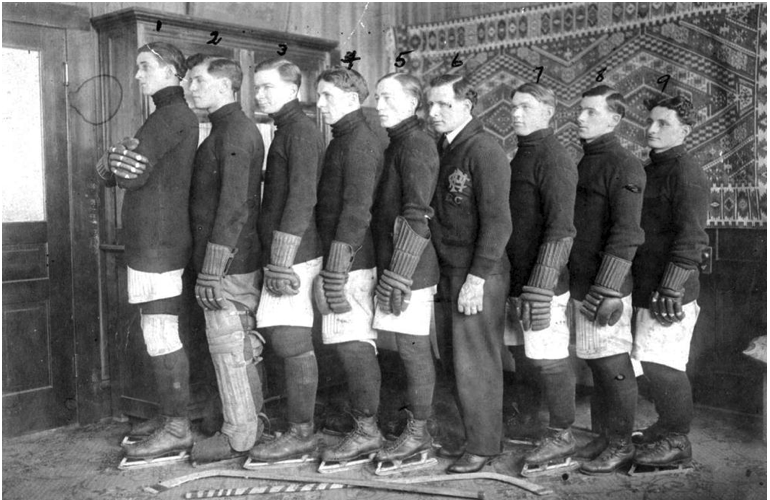

In 1911, the Phoenix hockey team won the provincial championship but were too late to qualify for the Stanley Cup. —BC Archives

For spectators, hockey meant an opportunity for placing bets—some as high as $1,000—on the outcome of the game, and many a goal meant the winning or losing of a small fortune.

By 1911, the population of Phoenix had grown to 4,000 souls, the town enjoyed electricity, a modern water system, its number of churches had grown by one, and the future look rosy. Between 1909 and 1911, the town shipped half of all the crude copper ore mined in Canada, about 7,000 tons daily, making it the largest producer in the country.

But, as early as 1909, dark clouds were forming on the horizon. Although the town continued to prosper, the Granby Company's engineers had warned that ore deposits were decreasing in metal values, and the company had begun to devote increasing attention to its Anyox properties on Observatory Inlet, near the Alaska border, as well as some coal reserves on Vancouver Island.

(To be continued)