Unbridled Lawlessness Was the Order of the Day in Gateway City

When, many years ago, I was interviewed by a radio announcer about my newest book, Outlaws of the Canadian West, he expressed amazement that we had ‘outlaws’ in British Columbia.

In the American Southwest, yes, but north of the 49th parallel? He could hardly believe it.

I had to convince him that we, too, had our own version of the Wild West.

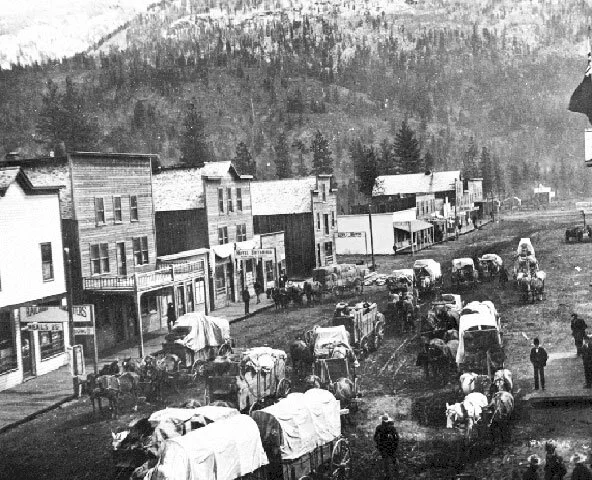

Boisterous, brawling Cascade City in the 1890s; it’s gone now. But it was exiting while it lasted! —Wikipedia photo

Nothing like Dodge City, of course; we’re British after all. But we had some real shootin,’ tootin’ desperadoes just like we’ve always seen in American western movies. (We even have the equal of the OK Corral; now there’s a story for a future Chronicle.)

Take this snapshot of gold rush Yale as captured by our old friend, D.W. Higgins:

“All was bustle and excitement in the new mining town,” he wrote in 1904. “Every race and every colour and both sexes were represented in the population. There were Englishmen, Canadians, Americans, Australians, Frenchmen, Germans, Spaniards, Mexicans, Chinese and Negroes–all bent on winning gold from the Fraser sands, and all hopeful of a successful season...

“In every saloon a faro-bank or a three-card monte table was in full swing, and the halls [saloons] were crowded to suffocation. A worse set of cut-throats and all-round scoundrels than those who flocked to Yale from all parts of the world never assembled anywhere.

“Decent people feared to go out after dark. Night assaults and robberies, varied by an occasional cold-blooded murder or a daylight theft, were common occurrences. Crime in every form stalked boldly through the town unchecked and unpunished. The good element was numerically large; but it was dominated and terrorized by those whose trade it was to bully, beat, rob and slay. Often men who had differences in California met at Yale and proceeded to fight it out on British soil by American methods...”

I’ve already told you of the fatal duel, ‘High noon in Downtown Victoria,’ when as many as 15,000 gold seekers passed through on their way to ‘Fraser’s’ River.

The fact is that a wide-open Fort Yale as described was an aberration but the challenge that faced, first colonial, then provincial authorities, in trying to maintain law and order on the Canadian West frontier was immense.

Which brings me to this week’s Chronicle about a gentlemanly English businessman’s exciting experience in trying to manage a store in the Boundary Country in 1897. Newly-born Cascade City had no provincial police officer, just a special constable with no training, and its ‘jail’ was a joke.

So it should have come as no real surprise when Stanley Mayall found himself plagued by a series of burglaries.

Petty crime, you say? So it seemed. Until the bullets began to fly!

* * * * *

Cascade Hotel, one of 14 in Cascade City at its peak . —Wikipedia

As the ‘colonial manager’ of a London-based mining and mercantile chain in the Boundary Country of British Columbia at the turn of the last century, Stanley Mayall enjoyed a number of adventures.

He shared some of these experiences with the readers of Wild World magazine—a gift, as it turned out, for posterity.

Stanley Mayall’s portrait shows him to have been something of the English dandy, resplendent in waistcoat, handkerchief, tie, bowler hat and gloves—hardly the costume of the wild B.C. frontier of more than a century ago.

Whatever Mayall’s taste in costume, he had a way with words, as his “straightforward little narrative” in Wide World shows. The following incident, in the words of editors, threw an “amazing sidelight on the rough-and-ready judicial methods of the frontier...”

At the time of this affair, Mayall was the general manager of a general store in Cascade, the so-called “Gateway City” near Grand Forks. Situated only a mile north of the international boundary, Cascade City was experiencing a combined mining, real estate and railway boom at the time.

As a result, the town served as a magnet to the businessman, the speculator, the labourer and the camp followers of society—in short, according to Mayall, “unbridled lawlessness was the order of the day”.

Cascade, he explained, was about six months old and had sprung into existence “to a fever [and] lived in a continual uproar... During the first year of the ‘city’s’ life I believe more than half the deaths which occurred were sudden ones.”

This being the case, one might be pardoned for dismissing a burglary as small potatoes. For Mayall, however, this particular burglary had greater personal meaning because of his starring role in the unfolding drama.

For three nights running he’d been disturbed by mysterious noises from the store below his quarters. Three times, he’d “risen hurriedly and discovered nothing. A fourth time I had heard noises below, but even a plank bed feels comfortable after 18 hours of hard work, and muttering, ‘It’s only a wandering cow,’ had shivered off to sleep again.”

The fourth time proved to be the real thing. Upon reporting for duty the next morning, his clerk informed him that thieves had broken in during the night and escaped with a shotgun and 120 pounds of tobacco.

The burglary had occurred in the depth of winter, with temperatures as low as -40 degrees F., and with between two to 20 feet of snow on the ground. The latter indicated that the break-in had been the work of amateurs or, at the very least, “a foolish and misguided bungle on the part of professional wrongdoers temporarily rendered careless by the apparent simplicity of the business at hand”.

Mayall based this unkind assessment of the burglars’ skill on the fact that they’d left several clear sets of foot prints in the snow; these, however, soon merged with the beaten paths of town traffic and the thieves couldn’t be followed further.

Naturally, the rush of business in the chief store of a boom town left little time for “detective business,” the aggrieved merchant continued. ”Carrying such a big and varied stock, embracing nearly everything from dolls to dynamite, we hardly knew what our losses really were.

“One thing, however, was clear—the stolen tobacco could hardly be for private consumption, and would consequently have to be marketed. The local markets were limited, consisting of a few minor stores and construction camps within a 30-mile radius.

“We accordingly sent out messages to all these, requesting that if the goods were offered for sale the vendor might be detained and ourselves communicated with. These measures taken, I went back to the store and was soon busily engaged in attending to the wants of my customers...”

Almost before he knew it, the proprietor of a small tobacco shop rushed into the store and exclaimed, “There’s an ugly looking son of a gun at my place offering T. and B. tobacco at about plantation price. Guess he’s stolen it. Come and get him!”

This announcement posed something of a problem as Cascade City lacked a constable. Unsure of just what to do, Mayall hurried to a colleague who also served as magistrate. This official promptly swore in Mayall’s junior bookkeeper as a special constable.

Morgan, a big, good natured Harrow graduate, was handed a revolver and instructed in the procedure of making an arrest. This, he proceeded to do in short order and the unsavoury-looking tobacco salesman, John Doon, was taken into custody.

The prisoner, who surrendered quietly, was placed in the town’s ‘jail,’ a ramshackle wooden house which served as living quarters to a carpenter and his wife, and doubled as occasion demanded as a combined courthouse and gaol.

Not unnaturally, Doon didn’t care for his accommodation and immediately asked to be allowed outside to exercise. Morgan, quite unused to his new duties, graciously consented, unbolted the door, then stood in open-mouthed astonishment as Doon ran, full-tilt, to freedom.

Upon recovering his senses Morgan charged in pursuit and after a lengthy chase and two warning shots, successfully recaptured his prisoner.

That evening, the tobacconist who’d reported Doon’s attempt to fence the stolen tobacco again called at Mayall’s store, this time to report that “another o’ them scoundrels [is] down at my place a-wondering where his pard’s gone. Come and get him.”

As he turned to go, he glanced at Mayall’s slight frame and suggested that, perhaps, he should take Morgan. “Bring your guns, for he’s an ugly ‘un, drunk too, an’ apt to fight like fury”.

Grabbing a revolver, Mayall hastened to the jail, collected his bookkeeper and proceeded to the tobacco shop where they found the suspect as reported. Unlike his partner, however, he didn’t surrender readily. Upon being told that he was under arrest, he plunged his right hand into a jacket pocket.

Mayall, prepared for the worst, pointed his pistol at the man’s head at point-blank range and warned him “not to move a muscle under penalty of having a bullet through him”.

“Then, and not till then, did he consent to come with us—and even then he came ungraciously.”

A search of his clothing uncovered a 12-inch bowie knife in his pocket. He was then marched along the crowded sidewalk to the jail where he was interned with Doon after being handcuffed, leg-ironed and chained to the floor.

“I shall never forget the ludicrous expression of astonishment on his face when he saw one of his companions already awaiting him,” Mayall recounted. “I must confess I was not a little startled myself when I heard the first whisper, ‘Where’s the other three?’ (Mayall was as yet unaware that Doon was the gang leader.)

“This gave the affair a somewhat serious aspect, for, if any actual [jailbreak] attempt were made by the burglars’ accomplices, the thin shell building—and, of course, my companion and self—could be riddled through in a few minutes.”

This realization did not make the wintry night any warmer and Mayall returned to the store for his overcoat and a rifle as he knew it would be necessary to guard the prisoners throughout the long night.

“Returning [to the jail] in no easy frame of mind, I found my Harrow friend oblivious to all sense of danger, and quietly enjoying a book and pipe. He was sitting with his back to the window, with the lamp lit, and the blind not even drawn down. When I suggested that, under such circumstances, his life was not worth one second’s purchase, he merely remarked, ‘Ah! Never thought of that,’ and continued reading.”

Obviously, Mayall thought, a public school education had its advantages.

That night was, the storekeeper declared, the longest of his life.

At any moment, he was convinced, the three members of the gang still at large would burst in on them. Although he and is companion were armed with two pistols and a rifle, Mayall was sure that, because of the cockle-shell construction of the jail, they’d be unable to withstand any form of attack.

The night dragged by but—finally—dawn broke without incident. Later that morning the prisoners were tried and convicted of being “rogues and vagabonds without visible means of support”—and sentenced to the maxim penalty of six months’ each.

They hadn’t been charged with burglary and attempted violence because to have done so—according to Mayall—would have required considerable time, trouble and expense.

On the B.C. frontier, he explained, the law was adapted to fit the offence. The trial, such as it was, was held was held at the scene of the crime, the general store which had provided the burglars with their booty also supplying the courtroom, magistrate, constables and the punishment.

Upon their being taken away, Mayall and companions were faced with the problem of the three missing outlaws. Mayall’s greatest fear was that, in retaliation, they’d set fire to his store.

“It would be the easiest thing in the world for the scoundrels to fire the store out of revenge...and I knew that, although we had about 30,000 dols. worth of stock in at this particular branch, it was only insured for about 10,000 dols.”

As it happened, the threat never materialized and, days later, he had the satisfaction of knowing that a third member of the gang had been arrested and confined in their gaol.

The town watchman, a giant Irishman named Pat Kennedy who’d taken no part in the drama thus far, was the hero of the second act. Upon passing by the jail late one night, he heard voices. Drawing both revolvers he crept forward to investigate, slipped inside and surprised the two missing burglars in the act of freeing the third prisoner.

Pat ordered them to put up their hands, at which one of the men drew and fired, the bullet lodging itself in the watchman’s chest and just missing his heart.

Thinking him dead, the two outlaws fled into the night. With a supreme effort, Pat staggered after them and opened fire. His first shot dropped one of them; moments after, a second shot found its mark in the other man’s leg and ended the pursuit.

This done, the seriously wounded watchman and his prisoners were given medical attention and, in due course, the recuperating burglars were reunited with their comrades in prison.

The capture of the last of the Doon gang meant peace of mind for Mayall, who concluded that, henceforth, burglars would give his store a wide berth.

He was wrong; within 36 hours his store was burgled a second time.

Although the burglars had been unsuccessful in their attempts to crack the safe they’d managed to disconnect the alarm to the till and escape with its contents. Mayall hadn’t slept on the premises this night, but two clerks who did slept soundly through the visit.

Mayall, however, had the satisfaction of knowing that the loss was minimal. At the time he wrote this article for Wide World, he admitted he had “no clue as to the robbers, and have little hope of making their acquaintance on the same satisfactory terms as in my former experience”.

* * * * *

If you Google Cascade City you’ll find that Wikipedia has based most of its entry on my account of Stanley Mayall’s encounters with the John Doon Gang, as I originally wrote it for my book, Encyclopedia of Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of British Columbia, Vol. 2.

Columbia and Western Railway Station at Cascade in 1899. —Wikipedia

Established as the “Gateway City” because of its strategic position just above the international boundary on the way to Grand Forks, and buoyed by mining and rail construction, the promise of a smelter, then hydro-electric power, Cascade City seemed assured of a solid future. At its height it had 14 hotels and “numerous” brothels, a sure sign of respectable prosperity.

But two devastating fires, the passing of the railway construction and mining booms, closing of the powerhouse and CPR station, and no smelter, ultimately proved fatal. Today a golf course occupies much of the historic town site whose cemetery survives on the opposite side of the Kettle River.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.