When British Columbia Had Its Own ‘Halifax Harbour’ Disaster

March 6, 1945

As I noted last week, I was reminded of the infamous Halifax Harbour blast of 1917 (Canada’s best known ‘big boom’ other than Ripple Rock) by an online reference to the east coast disaster’s 103rd anniversary.

Which in turn reminded me of our own west coast claim to a momentous maritime tragedy, the 1945 explosion of the steamship S.S. Greenhill Park in Vancouver Harbour in March 1945. 2020, of course, marks that tragedy’s 75th anniversary.

Until the collapse of the then-building Second Narrows Bridge (now the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge) in June 1958, it was Vancouver’s worst disaster in terms of lives lost.

So I rummaged in my library/archives and found the story of the ill-fated Greenhill Park which I originally published in a small chapbook way, way back in the dark ages of the early ‘70s.

Following as it does the tragic story of the air crash on Mount Benson, I promise that next week’s Christmas story will be on a lighter note!

* * * * *

A Vancouver Harbour tugboat sprays its firehoses on the smoking S.S. Greenhill Park. -- Photo Vancouver Sun

One of the many merchantmen to visit Pacific Northwest waters in the late 1960s was the Panamanian freighter, Lagos Michigan.

Few who noticed the rusting tramp load lumber would have recognized the respectable dowager as a lady with a past – a very dark past.

It was the Lagos Michigan, then the shining new S.S. Green Hill Park, which shattered Vancouver with the worst explosion in that city’s history. Eight men died and more than $1,000,000 in damage resulted on that infamous day of March 6, 1945.

Built in 1943 by the Burrard Drydock Company, the 425-foot Victoria ship had been launched as the Fort Simcoe. But it was as one of Canada’s famous wartime “Parks” that she entered Vancouver Harbour in February 1945 and tied up at the Canadian Pacific’s Pier B. After her annual refit, longshoremen swarmed over the ship, filling her yawning holds with lumber, tinplate, newsprint, chemicals and general cargo.

Incredibly, the S.S. Greenhill Park lived to sail again! -- Photo Vancouver Sun

Her manifest seemed innocent enough but, after the deadly blast, it was to become the centre of bitter controversy.

Loading continued on schedule until 11:45 a.m., March 6, when the cry “Fire!” swept the ship, sending supervising officers and longshoremen rushing for hoses and extinguishers. Crates were cast aside from Number 3 hold, where a thin veil of bluish-white smoke could be seen seeping through a ventilator. But, as water was poured onto the smouldering cargo, the smoke became thicker.

Then—a flame-spewing blast that rocked the vessel. In a deafening chain reaction three more eruptions followed, almost lifting the Green Hill Park bodily from the water, and creating a tidal shock wave that pummelled much of the city. Pedestrians near the waterfront were knocked to the pavement and warehouse doors were splintered from their hinges as 15,000 square feet of plate glass disintegrated, hurtling millions of glass slivers inward at the buildings’ occupants. Many office workers in the Marine Building and post office were lucky to receive only facial cuts.

Windows of the Canadian National Railways station, a mile and a half away, rattled violently. A federal government architect in Victoria said that there was not enough glass available throughout the country to repair the damage.

Burning wreckage of the ship was scattered over blocks.

Green Hill Park was a volcano of flame and smoke, seven and one-half tons of signal rockets flashing through the blackened skies – an eerie display of brilliant, carousing colours above the scene of carnage.

In the ship’s flaming holds were the charred remains of eight men.

Stevedore Ralph Atkinson, working in Number 3 hatch, had been one of the first to notice smoke. He and comrades had tried finding its source before it became overpowering, and they fled to safety. “We knew there was some inflammable liquid in cans,” he said, “also some flares, so we beat it out of the hold and I was the last out. Somebody must have been smoking.”

Albert Woods, an engineer on the neighbouring Bowness Park, was coming to visit a friend on the Greenhill, when he spotted yellow smoke and a flare ignite just as he stepped onto her gangplank. “I can tell you I sure started running,” he related.

Another longshoreman, M. Nahu, was working in Number 2 hatch when the first two explosions shook the vessel. “The third blast blew me into a save-all net. I picked myself up and then pulled two other men out of the water where they also had been blown.”

The first blast found stevedore J.L. Nesbitt in Number 8 hatch. The second knocked him onto his face in the oily darkness. Jumping up, he “ran to the rail where seven men were blown into the water.”

One of the Green Hill Park’s seamen saw a fellow crew member “killed when he attempted to run to the front of the vessel while the explosions were going off.”

Survivors swore that men had been flung seventy-five feet into the air by the awesome blasts.

Within twenty minutes of the first explosion, Red Cross nurses, led by Mrs. S.C. Fawcus, had opened a first-aid station on gutted Pier B. Scores of the injured, suffering from burns and shock, were rushed to hospital as more nurses hurried bundles of bandages and sterile dressings, blankets and hot-water bottles to the scene.

Meanwhile, ignoring warnings to stand clear, young Able Seaman Neil MacMillan manoeuvred the 50-foot Royal Canadian Navy harbour rescue craft Andamara alongside Greenhill Park, retrieving survivors who’d leapt into the harbour from blistering decks. Almost blinded by the intense heat, MacMillan and his heroic crewmen inched their way through a maze of swimming men and flaming debris.

Spunky little Andamara was “right under the ship’s stern when the third blast went off.

“We loaded as many as we could aboard our ship,” MacMillan later reported, “and we rendered first aid on the way to the dock. Then we went back to the scene and stood by.”

Two of Green Hill’s naval gunners, driven to the stern by heat, jumped to the decks of waiting tugs.

But no rescue crews could board the inferno.

“Thousands of office workers,” it was reported, “sprang from their noonday meals and poured along the main streets toward Pier B… Police cars, fire engines and ambulances raced toward the scene and a cordon of army, navy and air force police prevented spectators from getting onto the pier… The crowds fell back in order when police told them the ship might explode at any moment.”

Daring navy and civilian tugs and fire boats worried the still blazing ship out into the harbour then through the First narrows into open English Bay, beaching her on famous Siwash Rock. More explosions were feared every minute as the raging fires continued despite the thousands of gallons of water pumped onto them by firefighters.

Other ships, including the 10,000-ton Bowness Park, were hauled to the safety of Burrard Inlet, as more fire boats attacked the flames sweeping a lumber barge which had been moored alongside the Green Hill Park. (In command of the Bowness, but on leave during the excitement, was Capt. G. Ronald Newell, later Victoria’s harbour master who helped me with my original research).

Vancouver Harbour was choked with wartime shipping and several nearby vessels had been set afire by the blasts.

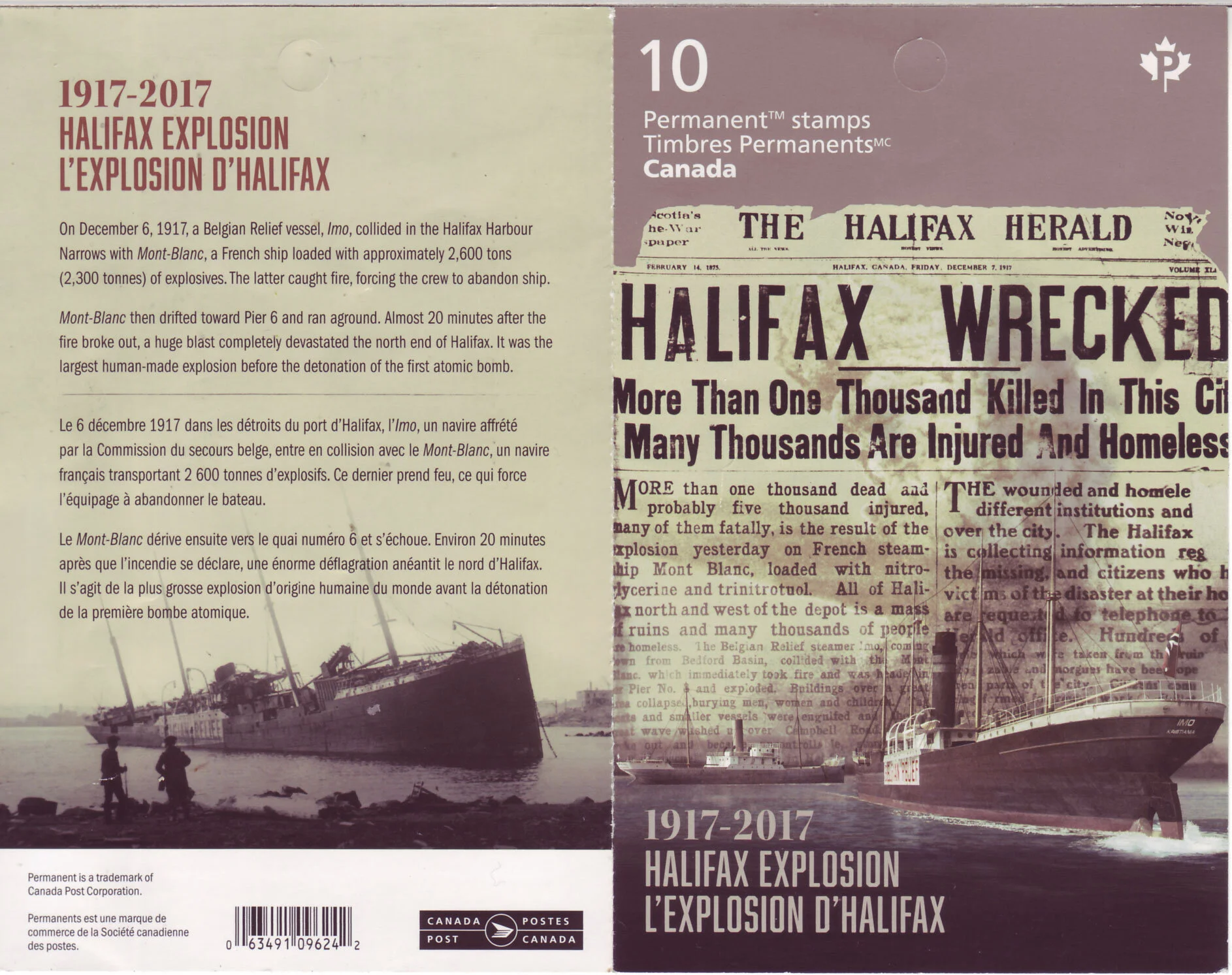

Fortunately, these were easily controlled. But, by late evening, Vancouver’s charred waterfront was described as being a “war scene,” and reminded many Canadians of the horrendous blast which had almost destroyed Halifax, 28 years earlier, when the French munitions ship Mont Blanc had collided with the Belgian relief ship Imo in the harbour. The ensuing holocaust killed 1,600 persons, injured 6,000 and left 20,000 destitute, and cost an estimated $25 million.

The Greenhill Park tragedy could scarcely be compared to this, but it was serious enough.

(Others recalled the unlucky date of February 13th, of two years before, when exploding dynamite razed Dawson Creek, B.C., killing five and injuring 150.)

Two days after the blasts, Greenhill Park continued to burn fiercely, her buckled decks too hot to walk upon and the recovery of bodies had to wait while firefighters battled the flames around the clock.

From Victoria, came the 2,400-horsepower tug Salvage Queen with a forty-man grew to take charge of salvage operations when the stricken ship could at last be boarded.

Attorney-General R.L. Maitland, KC, had already telegraphed the federal minister of transport to request a “searching inquiry” into the cause of the disaster. Many others were asking just what had caused the ship to explode, some hinting that she’d been loaded with munitions, which was against harbour regulations.

Others went so far as to charge sabotage.

The crews of the tugs Salvage Queen, Salvage Princess and Skookum joined the battle. Eventually the flames were beaten back far enough to allow exploring parties to examine the blackened, debris-littered and smouldering pit that was Number 3 hold. Two bodies, charred beyond recognition, were uncovered in the mire. Other salvors jettisoned lumber and pulp from Number 4 hold so that firefighters could move up with their equipment.

Said one of Salvage Princess’ men: “Steel is twisted in all directions, although the engine room has suffered little damage.”

Water lying in pools on the freighter’s warped decks was “boiling over” from the fires raging below.

As firefighters and salvors slowly gained on the blaze, federal authorities ordered a preliminary inquiry, the port manager was asked by the Vancouver mayor to begin a full probe, and the RCMP interrogated all longshoremen who’d been working aboard the ship before she blew up.

The list of casualties continued to grow with seven firemen being overcome by ammonia fumes while clearing the Greenhill’s refrigerator section. Rushed to hospital, they were discharged shortly after treatment. Of the 25 persons injured in the disaster, only eight remained hospitalized two days after the tragedy began.

By this time, three more incinerated bodies had been recovered from the wreck and three remained unaccounted for. Then another, unidentified man was added to the list of missing. Four of the five bodies recovered had been found in the water-filled bottom of Number 2 hold.

As the official inquiries into the tragedy got underway, a newspaper editorial voiced what many were asking: “How did it happen that a vessel with so volatile a cargo came to be docked in the centre of Vancouver’s waterfront, where an explosion could, and did, do $1,000,000 worth of damage inside of a few minutes?

“…What the public will wish first to be assured is on the question of accident or sabotage. Accident can spring from different sorts of facts, sabotage from only one, an enemy in our midst. Official reticence after the occurrence has not helped matters. The actual facts as to the human and other damage are coming out now, and they must be followed up until the amount is complete. Then, when the inquiry has had time to operate, the public will expect the answers to many questions that could be, and in part are being, asked now.”

An official of the Canada Shipping Company, operators of the Greenhill Park, felt impelled to make a public statement to the effect that “there were absolutely no explosives and no ammunition on board”.

He admitted, however, that 1,985 (actually 1,785) drums of sodium chlorate, for use as a weed killer, had been in Number 3 hold. Sodium chlorate was sometimes used in the manufacture of pyrotechnic explosives. Asking the most questions concerning the cause of the blasts was the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union which had lost six members.

At the coroner’s inquest, stevedore Neil Weir related his narrow escape. He had been working in Number 1 hold, he said, when his gang realized what was happening. Eight men had feverishly tried climbing up the single ladder from the hold. In desperation, Weir had scrambled up a rope. He recommended that the holds have four escape ladders.

Another longshoreman said he had heard someone shout: “All off the ship!” He and fellow workers had thought it merely the signal for lunch – until a ventilator hatch fell on them.

Stevedore Edward P. Sichavish had barely escaped from Number 3 hatch, signal flares exploding all about him….

Workers continued the grim task of clearing smouldering cargo and wreckage from the ship, searching for more bodies. One blackened corpse was found in what had been a passageway—just three feet from safety. Another was found at the foot of an escape ladder.

Six days had passed since the deadly explosions raked the Greenhill Park. Still the fires had not been extinguished.

Vancouver marine firefighters were busy again on April 3 when the lime cargo of the coastal freighter Bervin ignited, threatening to engulf the 256-ton craft. After a ten-hour fight by firemen and crew-members, the blaze was extinguished. Neither Capt. Garth Pengally, of Victoria, nor any of his men was injured.

The possibility of sabotage aboard Greenhill Park was discussed at the official inquiry, April 5, when Dominion analyst H.O. Tomlinson admitted that he had investigated this possibility for the RCMP. “But in my mind.” He said. “I am satisfied the sodium chlorate caused the explosions.”

The ship’s guards then disagreed with each other, two saying that no suspicious characters had been seen on board, that nothing unusual had occurred the night before the blasts. The third said he “thought sabotage was the only possible cause of the disaster”.

Also mentioned were two “mystery cases” which supposedly had been placed on board just before the explosion.

Vancouver residents realized just how fortunate they had been, five weeks after the disaster, when newspaper headlines announced in bold type: AT LEAST 360 DEAD, 1,730 HURT IN ITALY SHIP BLAST.

This had been the explosion of an American Liberty ship, loaded with aerial bombs in Bari Harbor. Besides the many dead and injured, harbour facilities were damaged and three other freighters caught fire.

The Greenhill Park inquiry continued, government experts trying to determine whether sodium chlorate, signal flares, fuel or a shipment of over-proof whisky had caused the fire and explosions.

Two mysterious soldered lunch pails were found aboard the wrecked ship, and a man’s jacket with hot water bottles sewn into the pockets, said the RCMP. Were these the tools of a saboteur? More likely, suggested a Mountie, they were devices for tapping an alcoholic cargo – “broaching” – and smuggling the prized liquor ashore.

The ill-starred S.S. Greenhill Park was rebuilt as the Phaeax II in 1946, renamed Lagos Michigan 10 years later, and scrapped in Taiwan in 1967.

In 1980 noted Vancouver historian Chuck Davis told of a deathbed confession by one of the longshoremen who was working in Number 3 hold when a flash fire ignited the first explosion. According to this informant, whose identity was withheld, several of the stevedores broached one of the barrels of whisky stowed in the dark hold. After several drinks one of them of them lit a match to see better and ignited the high-proof alcohol.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Canada Post marked the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Harbour explosion with a postage stamp in 2017. Few seem to have remembered that 2020 is the 75th anniversary of the 1945 S.S. Greenhill Park disaster in Vancouver Harbour.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.