When British Columbia Had Its Own Mint

Back in 1861, the Crown Colony of British Columbia was hindered by a shortage of money of all types.

At that time, the future Pacific province was supposed to be on the pound sterling of the Old Country. In reality, there was a shortage of coins and almost any coin of almost any realm was accepted if of gold or silver.

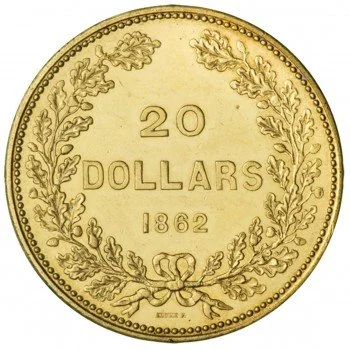

The 10-dollar and 20-dollar gold pieces produced by the New Westminster Mint. —bankofcanadamuseum.ca

After the discovery of gold in the Fraser River and the Cariboo, most newcomers to the colony were Americans who brought with them their own currency and coins. As well, Spanish dollars and currency issued by the Province of Canada (Upper and Lower) were legal tender throughout the colony.

The most common—and unsatisfactory—form of currency, however, was in the form of nuggets and dust; the solution, thought Gov. James Douglas, was to standardize the colony’s monetary system by issuing its own currency and coin, and he issued an order-in-council authorizing $75,000 worth of British Columbia bills, and to establish the B.C. Mint and Assay office in New Westminster.

* * * * *

“Calling for the new paper currency to be printed in dollar denominations was a bold step typical of Douglas,” one historian has noted. In his instructions to Capt. William D. Gossett, FRSE, of the Royal Engineers who also served as the colonial treasurer, he said, “the denomination of the notes must be in dollars as that is the notation of the account of the community at large".

Bank of British North America $1 note, 1859. Founded in 1837, the Bank of British North America opened its Victoria agency in 1859. (NCC 1964.88.325)—Royal Canadian Mint

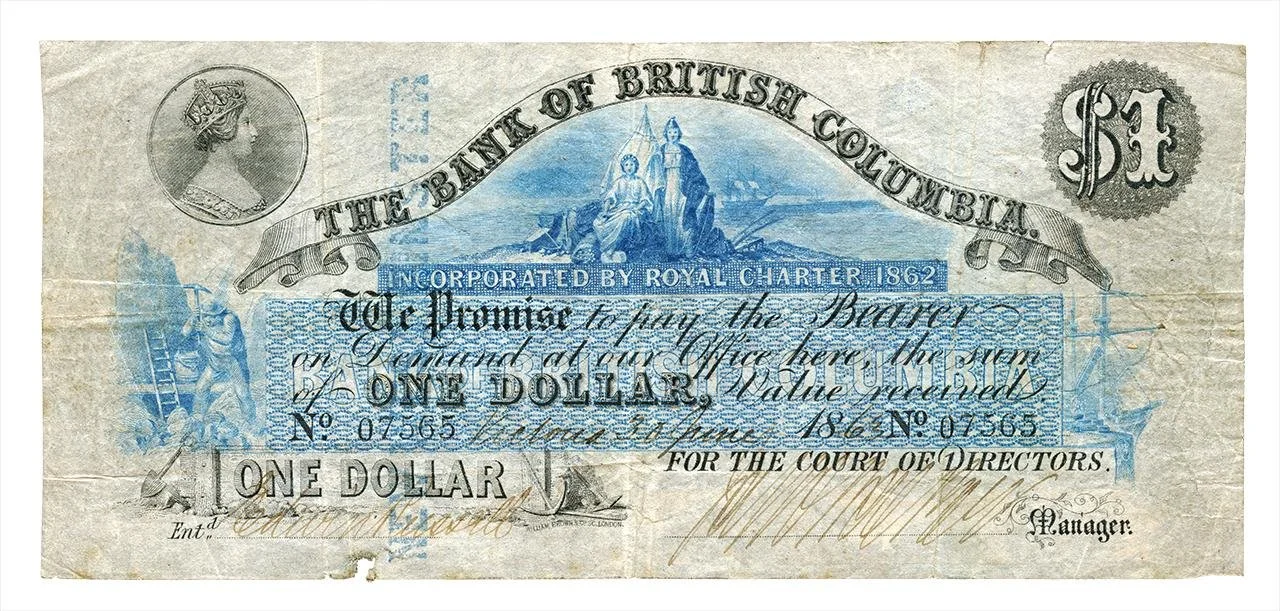

Bank of British Columbia $1 note, 1863. This note was overprinted for issue at the bank’s branch in New Westminster. (NCC 1963.53.4)—Royal Canadian Mint

As much as it must have galled Douglas’s British pride, it’s a tacit admission that, as most of the 30,000 gold seekers who’d invaded British territory were American, this was the most logical thing to do.

Gossett, who’s remembered more for his achievements as a land surveyor, was opposed to the plan; in fact, during his four years in the office of treasurer, he clashed with Douglas on several serious issues, including the colony’s bookkeeping.

“The notes were printed in Edinburgh on a special paper, watermarked 1860. Each was impressed with a seal signed by Gossett and the cashier, and countersigned by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, colonial secretary (and of Gothic fiction’s “It was a dark and stormy night... ") fame. Bills were issued in denominations of $25 (24,000), $10 (10,000) $5 (1,000).

And that—almost incredibly—was that.

As British Columbia is a legal entity and the notes were backed by the government of the day, they remain legal tender. Yet, as far as is known, the few notes that survive are in museums. Needless to say, they'd be worth considerably more than their face value to collectors.

Capt. Gossett was involved in the creation of another, greater numismatic treasure, the British Columbia 10- and 20-dollar gold pieces. The coins—18 of the $10 gold pieces and 10 of the $20, depending upon the source—were displayed in the International Exhibition of Industry and Art held in London that year.

At 32 millimetres in diameter, the 20-dollar coin is a hair bigger than a loonie.

According to Numista, it’s struck of .900 gold weighing 33.436g and round with a milled edge. The obverse bears a St. Edwards crown in the centre, surrounded by GOVERNMENT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA and a star underneath. The reverse has the denomination atop the date 1862 in a wreath, with the engravers’ initials, ‘Kuner A,’ below.

The initials are those of Albert (Albrecht) Kuner, of the Vanderslices Silver Manufactory in San Francisco. Considered to be among the best of West Coast engravers, he cut the dies for most privately issued gold coins of this period.

According to this authoritative source, 10 copies of the 20-dollar gold piece were created “with a distribution between two silver, one gold and one gilt variants...

“Five sets are known to exist and up to 10 may exist. The plan was torpedoed in London (as minting coins, especially gold, was a royal prerogative) and no further coins were minted until confederation with the rest of Canada... These coins in gold reportedly had the exact same composition and dimensions as contemporary American gold pieces (much as the later Canadian pieces would).”

After the Exhibition, during which the coins (designed by Capt. Gossett) reportedly attracted considerable comment, one of each denomination was presented to the British Museum. It’s a matter of legend if not fact that the rest were melted down and sold as bullion, and the New Westminster mint never struck another coin.

Fortunately for posterity’s sake, the dies are in the possession of the Royal BC Archives, Victoria.

A slight variant (of the several ‘reliable’ sources consulted for the writing of this post, most vary slightly on the numbers of each coin minted) of the New Westminster Mint saga was published in the Canadian Coin News, 10 years ago: “Miners...were being turned away to San Francisco to assay their gold, so a government assay office was established in New Westminster in 1860 but only functioned until 1867.”

The government’s desire to coin its own money set off a media feud between the Royal City and Victoria as Vancouver Island and mainland B.C. were then separate colonies. Both cities demanded that the mint be built in their bailiwicks.

It should be noted that Douglas and Gosset weren’t the only key players in the New Westminster Mint saga. As chief assayer for British Columbia, Francis George Claudet was dispatched to San Francisco to buy the necessary equipment and to see to establishing the new mint.

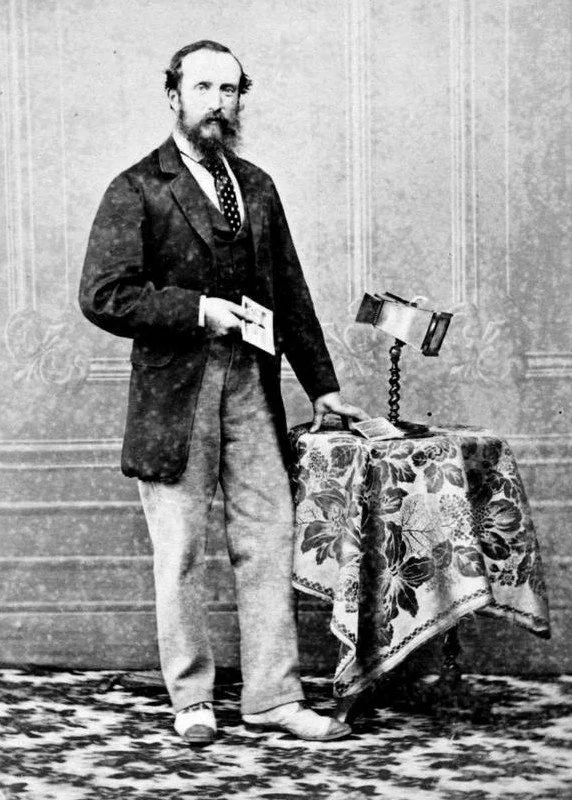

F.G. Claudet, ca. Mar 1870. Photographed in David Withrow's New Westminster studio, the inclusion of the stereograph viewer is intentional as a reminder of Claudet's connection through his father with the earliest years of stereoscopic photography. —BC Archives

Eventually, the coins’ dies arrived from San Francisco, and $5000 worth of minting equipment was also delivered—to New Westminster. By this time, however, Gov. Douglas seems to have had second thoughts, likely because of discouragement by his superiors in London. After withholding payments for the machinery’s installation, he then dragged his feet in appointing a qualified technician to operate it.

Reluctantly, he authorized the striking of coins to the value of £100 pounds for display at the 1862 London Industrial Exhibition—then decided not to submit them. Apparently, he had to be persuaded with great effort and, we can imagine, some anguish, to allow 28 coins: 18 of 10-dollars, and 10 of 20-dollars for Exhibition purposes—with the proviso that they be rendered into bullion after being displayed.

It’s believed that Gosset, as treasurer, kept two specimens and an undisclosed few found their way into the possession of other colonial officials.

By this time Gossett, coincidentally or otherwise, was on his way out of the treasurer’s office, as was the promoted Claudet, after this “single ‘mass’ striking. Another variant of the story reads: “...Only isolated copies of the coins were minted as souvenirs or proofs before Bulwer-Lytton managed to have the colonial government of B.C. abandon plans to go into full-scale production.”

They’re known as pattern coins, by the way, because they never entered circulation.

In November 1996, the remaining collection of the late U.S. Ambassador Henry Norweb and his wife Emery May came up for sale at a Baltimore, Maryland auction house. The Norwebs, who died in the early 1980s, were legendary numismatists, the total value of their collection having been estimated at $30 million. It was so huge that they were known to pack a picnic lunch and spend a day sorting through their treasures in a walk-in vault in Cleveland.

Son Raymond Henry Norweb sold the bulk of their collection in 1987 and 1988; the balance, including the B.C. coins, went to auction after his accidental death in 1997.

Among the Norweb treasures were a B.C. 20-dollar, and a 20-dollar and two 5- dollar coins in silver. The 20-dollar gold piece was expected to sell for between $100-200,000 US. (It went to a Massachusetts dealer for $143,000 US.) A Victoria numismatist noted that, at that time, the B.C. 20-dollar piece was “the largest-denomination Canadian coin ever made, and contains about an ounce of gold”.

Asked at that time about the three silver and two gold coins in the Provincial Museum, Archivist John Bovey said he’d like to replace the 20-dollar coin in their possession as it’s worn and has a hole drilled through it after having hung for years from Premier John Robson’s watch chain!

Robson’s grandson donated it to the museum in the 1950s.

Two more of these coveted coins turned up on display at a Royal Canadian Numismatic Assoc. show in August 2015. For several years, Sandy Campbell, owner of Proof Positive Coins in Baddeck, N.S., showed off three of the “gilt” coins he co-owned with Ian Laing, of Gatewest Coin Ltd., Winnipeg.

By this time, a mint condition set of the 20- and 10-dollar gold coins was said to be worth $2.5 million!

As noted, if you Google the B.C. Mint story you’ll find several authoritative sources, all of them varying slightly as to the number of coins, of gold and silver, and of their denominations. Again referring to Canadian Coin News, as of 10 years ago, five of the 10-dollar silver coins are known to exist, two of them in museums; two of the 20- dollar silver specimens are in museums.

Of the 20-dollar gold coins—again, those “known to exist”—three are in “institutions” (the British Museum, London, Eng., in the Royal BC Archives, and in the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce collection, leaving two in private possession.

Of the three known specimens of the 10-dollar gold specimen, the rarest of the four denominations, two (one in poor condition) are in museums and the third was co-owned as of 2015 by the two Canadian coin dealers cited above. Interestingly, theirs is a test sample kept by Albert Kuner, the coins’ die-cutter.

In 2017, the Royal Canadian Mint announced it had acquired two of “Canada’s most celebrated coins,” the 10- and 20-dollar B.C. gold coins, “part of the first official initiative to mint coins in Canada—almost half a century before the opening of the Royal Canadian Mint in 1908”. (These must be the Kuner-Campbell-Laing set.)

The official RCM website credits the bitter rivalry between New Westminster and Victoria for status as capital city for prompting Gov. James Douglas to place the equipment for the newly-built mint in the Royal City in storage: “This decision put him at odds with other government officials, setting off a media storm that lasted over a year. However, he gave approval for a few examples, called patterns, to be struck and sent to the 1862 International Exhibition in London. A few patterns were also unofficially struck as gifts for local dignitaries.

“Today, only a handful of these coins remains: a small number of silver pieces struck by the designer to test the dies and a few gold patterns struck once the minting machinery was assembled...”

The following RCM photos show that the BC coins were intentionally designed to be the same size and weight as the American “eagles” and “double eagles” coins that were in wide circulation in the colony.

British Columbia, $10 gold pattern, obverse side, 1862. The obverse design was the same for both the $10 and $20 denominations. (NCC 2016.50.1)—Royal Canadian Mint

British Columbia $20 gold pattern, reverse side, 1862. The designer’s name appears below the ribbon. (NCC 2016.50.2)—Royal Canadian Mint

United States $20 gold “double eagle,” reverse side, 1858. Struck at the San Francisco branch of the U.S. Mint. Note the small “s” for San Francisco above “Twenty D.” (NCC 1987.39.48)—Royal Canadian Mint

United States $20 gold “double eagle,” obverse side, 1858. The San Francisco branch of the U.S. Mint opened in 1854. (NCC 1987.39.48)—Royal Canadian Mint

I’ll leave the last word to the Royal Canadian Mint: “The BC gold pieces are a significant part of Canada’s material culture. They speak to the early development of Canada’s West Coast, the region’s economic ties to its natural resources and its early links to American markets to the south. More to the point, they represent the initiative of a fledgling province to assert authority over a virgin territory on the eve of Confederation.”