When Death Rode the Waves

As I noted in a recent editorial, 147 years later treasure hunters think they’ve found the wreckage of the SS. Pacific which foundered off Cape Flattery in 1875.

The result of a collision with a sailing ship, it’s one of the worst marine disasters in Pacific Northwest history—two survived of more than 250 persons aboard.

The sidewheel passenger steamer Pacific was old and tired—one of the so-called ‘floating coffins’ of the west coast in the so-called good old days of wooden ships and iron men—and she went down in minutes after receiving a glancing blow from the sailing ship Orpheus.

It’s a fascinating story of tragedy, complete with a message from the grave—and, if one chooses to believe, of a ‘ghost’ that tormented the Orpheus’s captain to his early grave.

* * * * *

Almost all Pacific Northwest ports fell victim as one shipping mishap occurred after another. But none was so staggering or as controversial as the wreck of the ancient steamer Pacific, but hours after she cleared Victoria, Nov. 4, 1875.

This appalling disaster—only two of more than 250 persons survived—is one of the worst in West Coast history. But the Pacific’s loss is vividly remembered because, as she went down, the sturdy vessel which rammed her mysteriously sailed on, leaving 100’s of men, women and children to perish.

Much reference has been made to this tragedy over the years. But the original puzzle remains. How, even in the perilous days of sail, could such an accident occur?

One important factor in the loss of life was the Pacific herself. Said the Colonist: “Built about 25 years since to supply a sudden demand for shipping in the California trade, she was not considered a safe boat 17 years ago when Captain Wright ran her in the Oregon and Vancouver Island trade; and steamers, it is well known, do not, like wine, improve with age...

“We earnestly hope that as this terrible visitation has sealed the doom of of nearly 100 [sic] human beings, it will also mark the close of the era of ‘floating coffins’ and ‘rotten tubs’ in the North Pacific. It is appalling to reflect that between a passenger and instant destruction there is but a thin plank. But when that plank is rotten as well as thin..!”

Few of the happy 100’s who pressed aboard the aging steamer could have appreciated her sorry condition. Families, miners and Chinese labourers lining her rails expected an uneventful passage “below” to San Francisco. They probably didn’t even realize that she was dangerously overloaded—some passengers had even climbed over the rail as the gangplank was raised.

S.S. Pacific struggled from Victoria at 9:30 on the morning of November 4. That night, she met her dreadful fate off Cape Flattery. But it wasn’t until four days later that Victorians learned of the calamity.

A special edition of the Colonist gave the few details then known and, in a grim editorial, the saddened editor wrote: “The catastrophe is so far-reaching that scarcely a household in Victoria but has lost one or more of its members, or must strike from its list of living friends a face or form that found ever a warm greeting within their circle...

“A bolt out of the blue could not have caused more widespread consternation...

“In some cases entire families have been swept away. In others, fond wives...have gone down to an early grave. In others, the joyous, happy maidens, the sweet, innocent prattling babe; the banker, the merchant, the miner, the public officer—all have found a common grave...”

An artist’s conception of the sinking of the S.S. Pacific, from The Mystic Spring and Other Tales of Western Life by D.W. Higgins, 1908.

Pacific had passed Tatoosh Light late in the afternoon, fighting a heavy swell and strong wind. Six hours alter, when the collision occurred, the tired coaster was just 20 miles from shore. Most passengers were asleep when the sudden crash sent them crowding on deck. The following nightmare is best described by one of her two survivors, quartermaster Neil Henley.

He’d just finished his watch at 8 p.m. and retired below when the Pacific shuddered under impact. Jumping from his bunk, he found “water rushing into the hold at a furious rate. On reaching the deck all as confusion. I looked at the starboard beam and saw a large vessel under sail, which they said had struck the steamer... The captain and officers were trying to lower the boats but the passengers crowded in against their commands, making their efforts useless.

“There were 15 women and six men to the boat with me, but she struck the ship and filled instantly, and when I came up I caught hold of a skylight, which soon capsized...”

While aboard the stricken Pacific, Henley had helped one lifeboat then assisted in lowering another. The first splintered against the Pacific’s hull, crushing a baby which had been placed in the boat by its mother, and drowning the other occupants. Henley jumped into the second craft but it “was so crammed with people she could not be rowed; I think the boat was damaged by coming against the ship, as I found she was also half-full of water immediately afterward.”

It was then that he struck out on his own, swimming to the steamer’s floating hurricane deck. When he looked for the ship, she’d disappeared. Already clinging to the hurricane deck were Capt. J.D. Howell, second mate A. Wells, a cook, another quartermaster, and three passengers including a woman.

Capt. Howell’s career had been a fascinating one. Brother-in-law of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, he’d been imprisoned with his famous relative after a gallant role in the rebel navy. Later returning to the sea, he’d skippered several coastal steamers. Shortly before his last command, his ship, the Los Angeles, had wrecked off Tillamook Head; after “encountering unnumbered perils, he’d reached the land and brought intelligence of the disaster to Astoria”.

Now he and his drenched companions shivered on their tiny float.

Pacific had gone down; no lifeboats were to be seen. Screams of the drowning haunted them in the darkness—then silence. The phantom ship which had struck Pacific her death blow sailed on into the night.

Then, said Henley, it was over; the cries had ceased and he and his companions were alone on the raft.

Then the sea began to steal his companions one by one: “At 1 a.m. the sea was making a clean breach over the raft. At 4 a.m. a heavy sea washed over us, carrying away the captain, second mate, the lady and another passenger, leaving four of us...

“At 9 a.m. the cook died and rolled off into the sea.”

The hours passed, the hardships increased. Late the following afternoon,”the mist cleared away, and we saw land about 15 miles away. We also saw a piece of wreckage with two men on it. At 5 p.m. another man expired, and early the next morning the other one died, leaving me alone. Soon after the death of the last man I caught a floating box and dragged it on[to] the raft. It kept the wind off, and during the day I slept considerable.”

Early on the morning of November 8, four days after the disaster, Henley was picked up the by the revenue cutter Oliver Wolcott. The haggard seaman suffered from exposure, shock, hunger and exhaustion. But he was alive.

Only one other survivor was found, passenger Henry F. Jelley having lashed himself to the Pacific’s pilothouse which had torn loose when the steamer sank. Rescued two days later by the bark Messenger, he first said Pacific had struck a rock south of Cape Flattery.

Rushed to port, he aroused the hopes of the crowds lining Victoria docks, waiting for word of missing relatives and friends. Jelley thought the two lifeboats had been safely launched...

A small fleet of rescue vessels immediately sailed in search of other survivors. Hundreds continued to wait and to pray at the waterfront for information. When the steamer Gussie Telfour docked in the evening of November 10, the pier was alight with lanterns and torches. The anxious crowd pressed forward, asking those aboard for any news. A deckhand wearily replied, “We’ve got two men and a woman, dead, and no one else.”

It seemed as if all Victoria had gathered there to mourn,” reported the Colonist. “Before the boat was made fast the eager throng passed over the guards and rushed back to the spot where three narrow, mound-like something [sic] covered with tarps showed that there lay the remains of three human beings whom, with 300 [sic] others, full of life and energy, sailed away from this port a few days before...”

The last body, that of a 25-year-old woman, was “scanned...for a trace of resemblance to some loved one known to have been on board the ill-fated ship”.

Silently, hundreds passed the tiny form, none able to say, “That was my daughter, or my wife, or my sister, who was lost in the Pacific.” “All shook their heads and turned away. Suddenly, “a prominent citizen” rushed forward and identified her. The crowd rejoiced, finding some satisfaction in the fact that she had been claimed.

In following days, more bodies and wreckage were found. A shattered rowboat drifted ashore near Victoria’s Clover Point. A grimmer discovery was the discovery of the body of attractive Fanny Palmer, 19, who’d sailed aboard the Pacific to join her sisters in San Francisco; her remains floated ashore almost at the very doorstep of her home.

The body of Gold Commissioner John Howe Sullivan was found at Becher Bay by Indians. He was interred in Ross Bay Cemetery.

Commissioner John Sullivan is in Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery. —Old Cemeteries Society

To date, nothing had been heard of the phantom sailing ship which had nudged the Pacific on that fateful night.

No one knew her identity or here whereabouts, and all prayed that she would soon dock with survivors. On November 16, the ghastly facts swept Victoria. Shocked and enraged, the city was in an uproar.

For it had been learned that the mysterious culprit was the American sailing vessel Orpheus, Capt. Charles A. Sawyer commanding. Ironically, Orpheus herself had become a total loss off Cape Beale, the morning after her collision with the Pacific. There were no Pacific passengers aboard her.

The common belief that Captain Sawyer callously sailed away, leaving 100’s struggling in the sea, fanned the entire Northwest into “lynch fever”. Even today it’s acknowledged that “so strong was this sentiment that he would have undoubtedly met with severe treatment had he been in the city [Victoria] at that time.”

The coroner’s inquest at Victoria sternly condemned the officers of both the Pacific and the Orpheus, charging that the former’s lifeboat capacity could handle but half her human cargo, that she was in deplorable condition, and that her lookout had been insufficient. Orpheus, it ruled, had “unjustifiably” crossed Pacific’s bow, and Capt. Sawyer hadn’t remained by the sinking steamer “to ascertain the damage she had sustained”.

Sawyer was then arrested in San Francisco on the charge he’d deliberately cast Orpheus away.

Acquitted of that absurdity, he found himself bitterly denounced and hated the length of the West Coast. Then his crew formally accused him of having deliberately deserted the Pacific—despite his having heard the screams of the dying.

At the official inquiry in the Bay City, Sawyer testified that his second made had mistaken Pacific’s riding lights for the Cape Flattery lighthouse. Due to the heavy sea, his deck watch hadn’t spotted the lights until they were almost onto the Pacific and it was too late.

“…She blew her whistle,” recalled Sawyer, “and immediately struck us on the starboard side in the wake of the main hatch. The blow was a light one. She had evidently stopped her engines and was backing up and gave us a glancing blow, for she bounced off and again struck us at the main topmast backstays, breaking the chain plates.”

Pacific had struck him again, he said, leaving him “comparatively a wreck on the starboard side”.

When his crew had rushed to their emergency stations, they found the Orpheus to be half-full of water, and Sawyer had set about repairing his ship, which engaged his attention “10 to 15 minutes”. He said he’d been too busy during this time to look at the steamer. Once safely underway, he’d looked back. But nothing was to be seen or heard. His men then commenced to berate the other vessel, he said, for not having seen to their injuries.

The court finally granted Sawyer the benefit of the doubt. He was widely respected (at least, up until this time) although a hard master, a trait which was thought to be the motive of his crewmen in trying to destroy him with their accusations. But the world was not as forgiving. Until his death in 1894, Captain Sawyer was cursed for having abandoned Pacific’s company to their deaths.

Several attempts have been made in recent years to salvage the Pacific’s safe, containing a Wells Fargo shipment of $79,220 in currency and gold. Many of her passengers had been miners returning from the Cassiar gold fields, and it’s thought that their wealth makes the Pacific worth as much as $10 million to the lucky finder.

The Cassiar gold rush was brief but rich and many of its more fortunate miners headed for the bright lights of San Francisco on board the Pacific. —Cassiar...do you remember?

However, the sketchy details known of her tragic end have made pinpointing her exact location extremely difficult although in 1961 American skin-divers claimed to have recovered several relics from her rotting hulk.

Three weeks ago the Vancouver Sun announced that the SS Pacific had been “found” after reports of fish boats snagging something on the bottom off Washington’s Olympic, and underwater scans showing two large circular objects which may be the Pacific’s paddles. In a subsequent story readers with a family connection to victims of the S.S. Pacific were urged to “stake your claim” by establishing their direct links to ancestors who may have been carrying their fortunes with them.

* * * * *

When Capt. Charles A. Sawyer died of heart failure in Port Townsend 20 years after the notorious shipwreck, he was just 54 or 55. According to Find A Grave, his daughter had his remains returned to his ancestral home in Glooucester, Massachusetts, for burial.

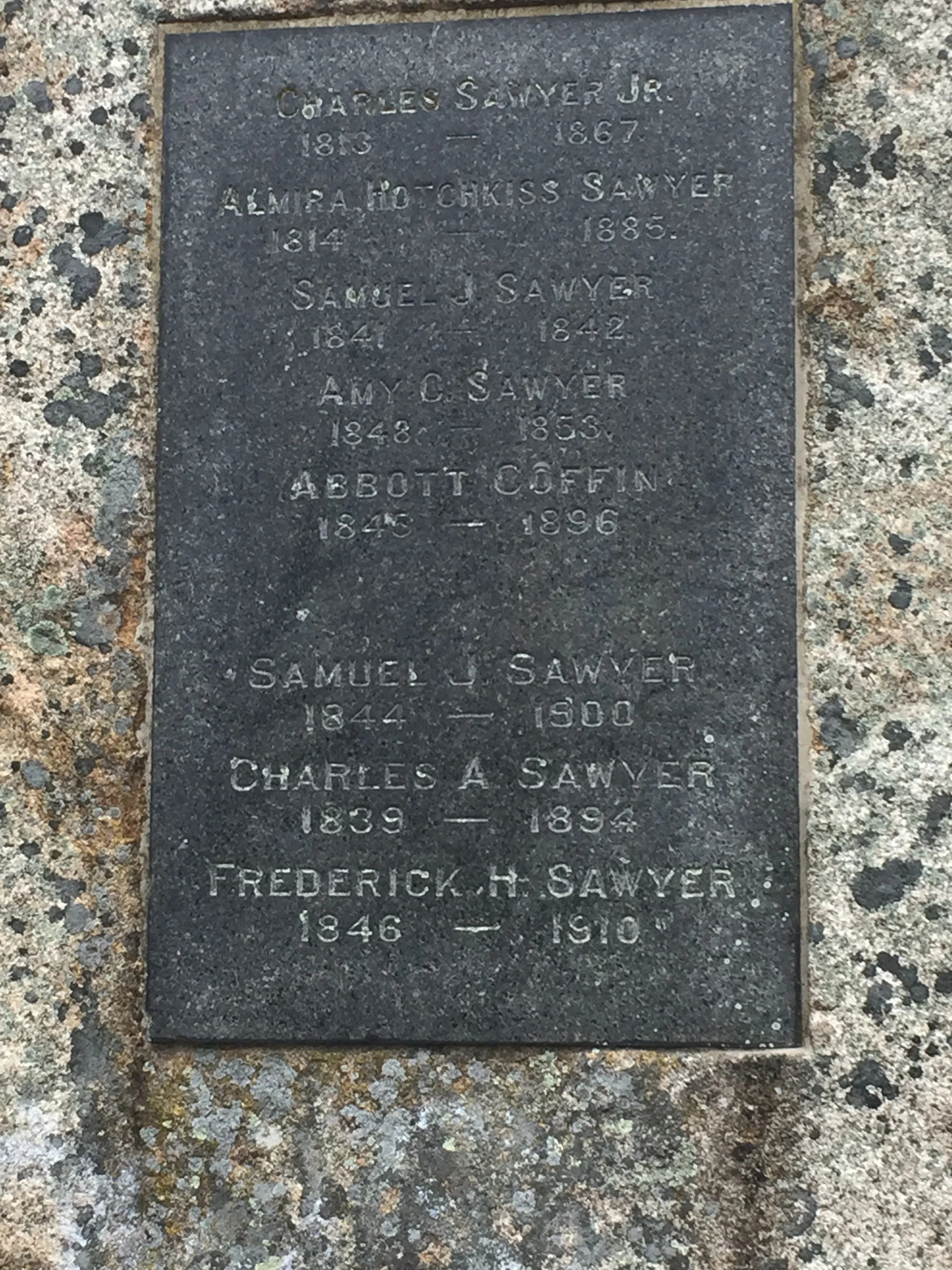

Capt. Charles A. Sawyer’s bronze marker in the family plot in his hometown of Glouceser, Mass. —Find A Grave

Wife and daughter (who’d been aboard the Orpheus at the time of her collision with the Pacific and subsequent shipwreck) or no, by all accounts he died a very lonely man. For many years, it was reported, he hadn’t dared to visit Victoria where feelings continued to run high against him. In fact, in the weeks immediately following the collision, he’d been forced to hide in the home of the port Townsend collector of customs.

Upon news of his passing, in 1894, the Colonist noted: “Captain Sawyer in later years suffered much from the recollections of the sad event.

“An incident occurred not long ago in Port Townsend that aptly illustrates his peace of mind. He was visiting a neighbour one evening, the conversation lagged, and he was gazing intently into the glowing grate for several minutes and then suddenly exclaimed: ‘There, I heard the whistle plainly.’

“In explanation, he said he could hear distinctly the Pacific’s whistle, and that it was a constant worriment to his peace of mind...”

* * * * *

I’ve told the story in a previous Chronicle of pioneer lumber baron Sewell Moody who was one of the Pacific’s victims.

In just 14 years, it was said, Hartland, Maine businessman Sewell Prescott Moody “set frontier British Columbia on the road to industrialization”. His career was cut short when he went down with the Pacific. —Wikipedia

Mourned the New Westminster Herald: “A gloom was cast over the community by the receipt of the sad intelligence of the loss of the Pacific, many of the victims being known and esteemed here... One of them, Mr. S.F. Moody, was among the foremost men in the new Westminster district, and whose loss will be at once sincerely regretted and widely felt.

“Always ready to hold forth in manner, enterprising and energetic in business and the head of a large and wealthy firm—he was one whose place will not easily be filled.”

Many mourned the Maine businessman whose humour, honesty and regard for his workmen had made him universally popular. Few were prepared for the shock of learning that, in death, Moody was to have the last word.

This macabre twist occurred in Victoria when a resident walking along the Beacon Hill Park shore came upon a length of board, later determined to be a piece of wreckage from the hapless Pacific. What caught the beachcomber’s eye was the brief message which had been pencilled on its painted surface:

“S.P. Moody, all is lost.”

Immediate reaction to the discovery was that a “heartless hoax” had been perpetrated by someone with a perverted sense of humour who, upon finding the board on the beach, had written the message then launched the plank again.

But when friends identified the writing as being as that of Sewell Moody, it was “supposed that when the vessel was going down he wrote the inscription on one of the beams of the stateroom with the faint hope that the board would be found and his friends informed of his fate.

“If such were his purpose it has been attained by the casting up of the fragment after it had floated nearly 100 miles on the breast of the hungry sea, and reached the shore within sight of the deceased gentleman’s home. The feelings of a man taking leave of life under such circumstances can neither be imagined nor described.”

* * * * *

It will be interesting to see if, in fact, the remains of the Pacific have been found and whether salvors can recover any of the fortune that’s supposed to have been on board. The suspected paddle wheels, 1500 feet down, are well within reach of today’s high-tech salvage methods.