When Navy Cannon Ended Chemainus Potlatch

March 1878: Indians Defiant! H.M.S. Rocket to the Fore.

April 2021: Island RCMP officer recognized for reconciliation work with First Nations

We like to think that history repeats itself. Maybe yes, maybe no. But there’s no doubting that history does an about-face from time to time. You couldn’t find a greater contrast between these two news stories, which occurred 143 years apart, if you tried.

A blanket potlatch. —W.M. Halliday photo.

The first, which appeared in the Nanaimo Free Press, consists of an entire column that, by today’s standards, is a prejudiced account of a police raid on a potlatch held by members of the Penelakut Tribe. (Members of the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group, the Penelakuts’ largest reserve is on Penelakut (formerly Kuper) Island, midway between Chemainus and Ladysmith.)

That was in 1878. Today we recognize the cultural significance of the potlatch to B.C. First Nations. But for over 60 years this celebration, noted primarily for its ceremonial gift-giving, was outlawed, proponents subject to fines and imprisonment, precious tribal icons subject to seizure and sale. I’ll explain a potlatch’s meaning and purpose, why it was banned, and its present status in due course.

Let’s begin with the incident involving HMS Rocket in 1878. Please note that I’m adhering to the account as it was reported in the Free Press.

With the avowed purpose of “preventing, if possible, a breach of the peace,” Nanaimo’s Chief Constable Stewart and Special Officers Jenner, Brown and Lusty paddled south for Chemainus. Off Yellow Point they overtook a canoe containing four natives and a quantity of liquor and, convinced that crew and cargo were potlatch-bound, arrested them. They then waited for the mail steamer Pilot, expected momentarily, to hitch passage back to town.

Instead of the packet, however, they saw five canoes, paddled “with a vim and vigour” that matched steamboat speed, headed their way.

Alarmed, Stewart and company began to paddle furiously but were quickly surrounded by angry natives who, at gunpoint, demanded the release of the prisoners and whisky cargo.

“One hundred against four being altogether too great odds to contend against,” reported the Free Press in the contorted prose of the day, “the prisoners and canoe were given up, and the discomfited officers of the law wended their way back to Nanaimo.”

Judicial response was swift and decisive.

When Government Agent Fawcett informed authorities in Victoria by dispatch, “without any ‘red tape’ or circumlocution,” the gunboat HMS Rocket was ordered to Chemainus. Upon her arrival just 60 hours after the prisoners’ escape, Capt. Harris, B.C. Police Supt. Bowden and Const. Stewart’s posse began a search for their original prisoners and the ringleaders who’d freed them.

To discourage any thoughts of resistance by the 1,000-odd persons attending the potlatch, Harris made a show of bombarding a nearby uninhabited island with his cannon. This had the desired pacifying effect but created some excitement in Nanaimo when residents, hearing the distant thunder of heavy guns, assumed the worst.

Next morning the Rocket arrived at Nanaimo with 13 prisoners, 12 men and a woman.

Only one was from Chemainus, the others having attended from as far away as the lower Mainland and Washington. Court proceedings before Mayor Mark Bate and J. Planta, J.P. were brief. For obstructing Const. Stewart and his men in their duties, Qualicum, Tom Qul-cla-elum and Joe Halkemet were each sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, $50 fine—and $25 costs—in default, an additional three months behind bars.

Joe Swanissett, of Quamichan, received the heaviest sentence (four months, $75 fine, $25 costs) for waving a gun at Stewart.

For their smaller roles the others received lighter sentences, only Tom Kutsame, of Somenos, refusing to plead guilty. He was committed for trial at the spring assizes. (As this meant he’d have to bide his time behind bars it’s interesting to note that he chose to argue his innocence whereas the others submitted to the lower court’s rulings.)

Two further arrests were made after the Chemainus affair.

All pretty dramatic, I’m sure you’ll agree.

Coppers’ were highly prized by northwest coast tribes; to break one at a potlatch meant great sacrifice on the part of its owner who, in return, earned high respect. —Photo: www.pinterest.com

Fast-forward to 2021 and a Times Colonist report of RCMP Cpl. Chris Voiler receiving a B,.C. Reconciliation Award for his role at a potlatch held by the Nakwaxda’zxw First Nation at Port Hardy the previous year.

What a leap!—from the authorities, in the first instance naval and provincial police, descending upon a potlatch with cannon and a posse—to a member of our national police force being feted at a such an event.

So what was the fuss all about?

First, let’s understand the meaning of potlatch. Coined from Chinook, the ‘trade jargon’ used from the days of the fur trade to communicate in a mixture of English, French and various tribal tongues, it means “to give”.

You’ll find a dozen definitions of the potlatch which was common to Indigenous peoples from Alaska to Oregon and probably reached its popular and cultural zenith with northern Vancouver Island tribes after the arrival of Europeans until its banning by law in 1884. Here are just a few meanings of the term, particularly as it was viewed by provincial and church authorities:

—A ceremonial feast...marked by the host’s lavish distribution of gifts or sometimes destruction of property to demonstrate wealth and generosity with the expectation of eventual reciprocation

—To give (something, such as a gift) especially with the expectation of a gift in return

—A ceremonial feast...as in celebrating a marriage or a new accession, in which the host gives gifts to tribesmen and others to display his superior wealth (sometimes, formerly, to his own impoverishment)...

—A ceremonial festival at which gifts are bestowed on the guest and property is destroyed by its owner in a show of wealth that the guests later attempt to surpass

—A ceremonial feast...at which the host distributes gifts according to each guest’s rank or status. Between rival groups the potlatch could involve extravagant or competitive giving and destruction by the host of valued items as a display of superior wealth.

—A ceremony integral to the governing structure, culture and spiritual traditions... While the practice and formality of the ceremony differed among First Nations, it was commonly held on the occasion of important social events, such as marriages births and funerals. A great potlatch might last for several days and would involve feasting spirit dances, singing and theatrical demonstrations.

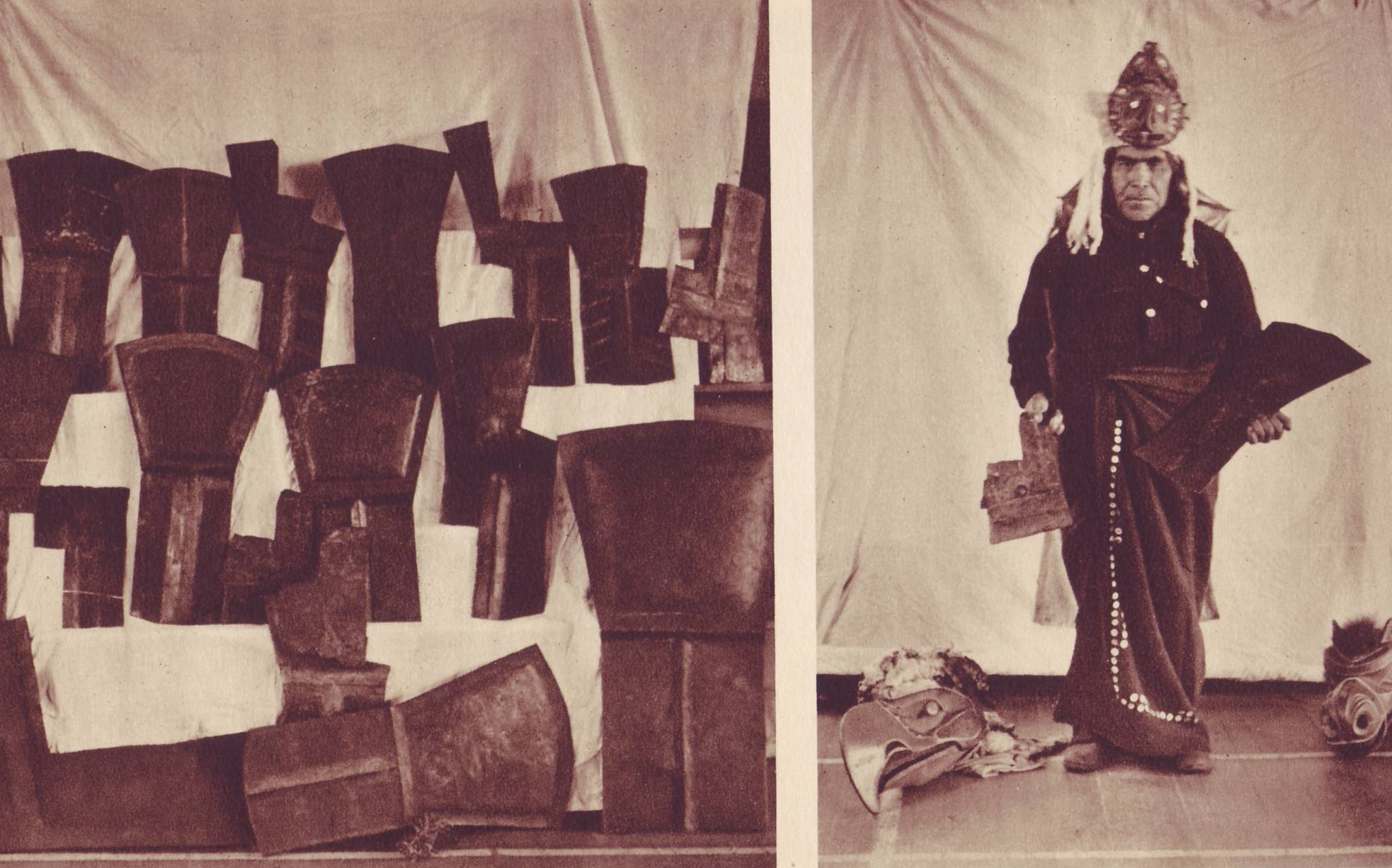

A collection of coppers and the paid orator at a potlatch posing with coppers. —W.M. Halliday photos.

To the various churches out to save souls the potlatch was un-Christian.

To the federal government, with its avowed policy of assimilation, the potlatch was rebellious, wasteful of money and goods, and beggared its practitioners, their families, sometimes even their tribes for years or generations.

Let’s leave it there for a moment and turn to a man who was at the forefront of the drive to stamp out the potlatch and its professed sins. (It’s interesting to note that, before joining the Department of Indian Affairs he’d attended, as a guest, a potlatch at Comox which had impressed him not unfavourably.)

Ontario-born William May Halliday came to B.C. with his family in 1873 and as a young man homesteaded with a brother at Kingcome Valley for four years before moving to Alert Bay to serve as assistant principal of St. Michael’s Residential School. In 1906 he became the Indian Agent for the Kwakewlth Agency serving the north Island and the adjacent Mainland coast.

During retirement he wrote Potlatch and Totem: Recollections of an Indian Agent, which was published in 1935.

It’s only semi-autobiographical and the chapter of the most interest to us today is entitled ‘Matters Judicial’ where he cites various cases he dealt with as a Justice of the Peace, in particular the resurgence of the potlatch in 1921. (Please note that, like it or not, ‘Indian’ was the accepted term of that time.)

* * * * *

William Hallliday: ...Possibly the most interesting cases of offences against any statutory enactments would come under the prosecutions that arose from infringements of that portion of the Indian Act which deals with the potlatch.

The act had been on the statute-book for many years without being enforced. It was thought that education and missionary training amongst the Indians would so open their minds to the folly of the custom that the custom itself would die a natural death without any legal proceedings having to be taken to compel it to die.

However, things gradually got worse and worse.

The potlatch was assuming greater and greater proportions, and instructions were received from the Department of Indian Affairs to enforce the regulations and see that this custom was done away with entirely. Notice was given to all the Indians both by letter and personally, as I made it my business to call on every Indian village in the agency, and when the people were all assembled together, to tell them that the Department was being compelled to put into force the legislation against the potlatch. and they were warned to govern themselves by what they were being told.

It was a matter that so far as the agent was concerned admitted of no argument, as instructions had come direct from headquarters. At that time the Act made it an indictable offence to engage in these ceremonies, and the first prosecutions were entered by the provincial police against two Indians living at Alert Bay, both of whom were particularly good fellows in other ways.

I committed them for trial, and they went to Vancouver and were let out on bail, pending a meeting of the assize court.

When they appeared in the assize court before Mr. Justice Gregory, they pleaded ‘Guilty.’ I was present at the court, and Mr. Gregory asked me as to the character of these two men, and I told him that they were good fellows, law-abiding in every other way. Consequently, they were given a reprimand and told to warn the other Indians, and were allowed their liberty on suspended sentence.

It seemed apparent that to operate this section of the Act properly, the act itself should be amended, as that was the only section of the Indian Act which did not admit of some jurisdiction by the Indian agent or two justices of the peace, and accordingly the Act was amended, making it a summary conviction.

Four Indians from Kingcome Inlet were brought up for summary trial. They had been having a big feast and had broken a copper as a sort of spite against some enemy they had, and in conjunction with the breaking of the copper they were compelled by custom to give away some considerable quantity both of money and goods, which brought it under the category of an offence against Section 149 of the Indian Act, as it was at that time.

Sold to museums and collectors for bargain prices, these masks would be considered priceless today. —W.M. Hallliday photo.

Mr. E.K. DeBeck of Vancouver, whose father at one time had been Indian agent of this agency, defended them, but they were convicted and sent to Oakalla prison for two months. An appeal was made against my decision, but the appeal was dismissed by Chief Justice Hunter.

Several more Indians were arrested by the [RCMP], who at that time were sent here to assist in the maintenance of law and order and to carry out certain other work in connection with the government of the Dominion of Canada. Mr. Frank Lyons of Vancouver was instructed by the Department to attend and prosecute.

The trial lasted all day, and was adjourned until the next morning.

Mr. Lyons was very desirous that his clients should not be imprisoned (the Act allows no other penalty), and talking the matter over with the Indians, themselves in court, he made the proposition that the Indians should refrain from this custom for all time, as it never was the desire of the Department that the Indians should be punished unnecessarily, their sole aim and object being to better their conditions by having them give up the potlatch custom.

This was assented to, and an agreement was drawn up and signed by the Indians in question, also assented to by the Crown and countersigned by the Indian agent. The Indians in this agreement not only pledged themselves to refrain from potlatching any more, but to use their influence to prevent any other Indians from holding any of these prohibited ceremonies. In order that the court should be made more impressive, both counsel wore their gowns during the proceedings, and by so doing added a certain dignity and impressiveness to the court, which afterwards bore good fruit.

Suspended sentences were given to all these Indians subject to their good behaviour in the future.

It was explained to them that this did not take away their right to make what efforts they could to have the law amended, but no hope was held out that they would be successful in their efforts.

For some considerable time the Indians obeyed the law, and it was thought that in a very short time they would have forgotten all about this ancient custom. Some two years later, a big gathering was held at Village Island at the home of the Mamilillikulla [Mimkwamlis] tribe and not only was the ancient custom of redemption carried out, whereby one man was enabled to give a very big potlatch, but in addition an unusually large amount of property had been collected and was given away in due and ancient form.

(This was the Christmas 1921 Dan Cramner potlatch which is said to be the largest potlatch recorded on the coast of B.C.—Ed.)

Sergeant Angerman of the [RCMP] acted very promptly in the matter, and about eighty Indians were summoned to appear to answer to the charge of the violation of this section of the Indian Act.

Sergeant Angerman was an old hand at conducting prosecutions and was as efficient as the average counsel, and he had such strong evidence that he did not think it necessary for the Crown to engage a counsel to prosecute as he was quite competent to do the prosecuting himself, and an array of legal talent came to Alert Bay for the defence.

Mr. Finlay...a Mr. Ellis, Mr. Campbell, and one or two others, all appeared for various members of those who were charged with potlatching. The trial lasted some considerable time, and then their counsel made another proposal to the Indians to the effect that as the first agreement had had ony been signed by a limited number of Indians, none of whom was concerned in the present offence, an additional opportunity would be given them to escape from punishment.

The conditions attached to it were that they were not only to promise they would refrain from potlatching, but that they were also to use their influence to see that nobody else took part in any of these proceedings; and in addition to this, they agreed to surrender all their potlatch paraphernalia, such as dancing-masks, head-dresses, coppers, and various other things, which would be sold to the various museums by the Department of Indian Affairs and the proceeds given over to the Indians.

Those who had been most active in the carrying on of this potlatch were the most active in trying to persuade their friends to join with them in signing the agreement or in assenting to it, and thirty days was given them to collect the paraphernalia in question. At the expiration of the thirty days it was found that practically all the Indians with the exception of those at Kingcome Inlet had signed the agreement and surrendered the paraphernalia.

This was all carefully tabulated and shipped to Ottawa and, later on, cheques were received reimbursing the owners.

The sum realized the Indians considered entirely inadequate, but this is a matter on which opinions differed very much. Some of the things for which good prices were paid, the ordinary individual would not consider worth anything at all, while some of the things were more or less new and though in many instances were much better looking, they only brought fair to low prices, as to those learned in the antiquities of the Indians they had little historic value.

(What value would be placed on these artifacts today?—TW.)

Another view of masks about to be surrendered to the federal government to avoid imprisonment. —W.M. Halliday photo.

When all had been completed, the whole of the offenders, numbering sixty-five, were collected together for sentence. Those who had refused to accept the conditions as laid down were sent to prison for two months, and the rest were given suspended sentence.

It so happened that there were two amongst the defendants to whom suspended sentence could not be given, as theirs was a second offence, but as the part taken by them had been very minor, their sentence was delayed and a recommendation sent through the Department of Indian Affairs to the Department of Justice, asking for special authority to allow suspended sentence to these two.

Later on another prosecution was entered by the [RCMP] against some Indians of the Nakwakto band, whose headquarters were at Blunden Harbour, and they were sent to jail for two month.

It may be noted here that these prosecutions and the sentences imposed made the Indian agent extremely unpopular amongst the Indians, and extremely unpopular with a certain number of outsiders who were not interested in the matter at all, and who, not realizing the reasons which lay behind the whole thing, were inclined to think the proceedings were very arbitrary, and that the personal liberties of the Indians were being taken away from them.

I received two anonymous letters, which were treated with the contempt they deserved.

One of these referred to certain actions done by the Klu-Klux-Klan, and they stated that people of my type should be treated in the same manner as the Klu-Klux-Klan had done, and should either be put out of the way or tarred and feathered.

Since that time the potlatch has been gradually dying away, and in no instance has it been done openly. Under the statute it has to be proved that it is an Indian festival, dance, or ceremony, and also it must be proved that at this Indian festival, dance, or ceremony, the giving away of money, goods, or articles of any sort formed a part of or was a feature.

There have been a number of instances where people who felt they must give away have done it surreptitiously. They would travel in a boat to the village where they felt it was incumbent on them to give something away, and, while there, call the people individually to the boat and give them what they intended. This method, of course, freed them from prosecution, as there was neither ceremony, dance, nor festival in connection with it, but on the other hand, there was no eclat attached to the one who gave it, and the affair would fall very flat.

The potlatch has tended very materially to retard progress amongst the Indians.

It has set up false ideas amongst them, and has been a great waste of time, a great waste of energy, and a great waste of substance [my italics—TW]. However, apparently it will take some time before the idea of the potlatch will be entirely eliminated, and when that is done progress will be extremely rapid, as the Indian of to-day, apart from these ideas, is inclined to be progressive.

As matters have turned out, these prosecutions came at the right moment for many of the tribes. Some of the younger men were fully conscious of the evils of the system, and wanted to break away from it. The older ones, who were wedded to the custom, were very much concerned over these young and thinking men trying to get free from their laws and regulations, and had even gone so far as to warn them that if they carried out their intention, they would be obliged to sever all connection with the Indians living on the reserves. When the Act was enforced, it strengthened the hands of the young men and weakened the influence of the older men, with the result that in those villages there has been a very rapid improvement and advancement.

* * * * *

In the introduction to Potlatch and Totem Halliday summed up his view of the potlatch thusly: “Having been a resident amongst the Indians for thirty-eight years. [I have] had many opportunities to thoroughly examine all phases of the potlatch, and the conclusions arrived at after intensive study have been that the good obtained from it was so small, and the evils associated with it were so great” that the Department of Indian Affairs was “well advised” in banning the practice.

In his view the potlatch had a single redeeming feature” “...During the times of these gatherings the aged, infirm and destitute were fed by those engaged in the giving away”.

Whatever one chooses to think about Indian Agent William May Halliday today, there’s no doubt that he sincerely believed that he and the government were right, that they were acting in the best interests of First Nations across Canada.

Now that he has had his say, let’s turn the telescope around and see what various Indigenous groups currently think about the potlatch:

While one source recognizes that it was the “competitive potlatches” with their increasingly lavish property giving that sparked the concern of settlers and church leaders, then the government, others are more damning.

The Bill Reid Centre of Simon Fraser University sees the potlatch as “much more than a gift-giving feast,” that it was “once the primary economic system of Coastal First People...and intricately woven into the social fabric of coastal societies”. For a full explanation of what a potlatch really stood for please see www.sfu.ca/brc/online_exhibits/masks-2-0/the-potlatch-ban.html.

Here’s BRC’s bottom line:

“The purpose of of the [potlatch] ban was explicit. It was intended to stamp out aboriginal people and their culture. Coastal First Nations were persecuted, chiefs and noblewomen were jailed for practicing [sic] their culture, masks were confiscated. Big houses were torn down, and ceremonial objects were burned.”

The 1921 potlatch described by Halliday ended, according to this source, with 22 people being jailed and the seizure of more than 600 pieces of cultural art—masks, rattles and other treasured regalia and family heirlooms that were later exhibited (before their sale to museums and private collections) as “trophies’ in the Anglican church at Alert Bay.

The indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca sees the Indian Act itself as “part of a long history of assimilation policies that intended to terminate the cultural, social, economic, and political distinctiveness of Aboriginal peoples by absorbing them into mainstream Canadian life and values”.

It wasn’t until 1951 that Canadian authorities rescinded the ban on the ceremonial potlatch, four years after First Nations peoples were granted the right to vote provincially.

Postscript: I’ve given Indian Agent Halliday the greater say in this post with the intention of trying to convey the governmental mindset of his day.

Today, in 2021, we’re still—just—coming to terms with 400 years of mishandling our relationships with our First Nations. How did we get to where we are now? Was it all just the conscious and deliberate exercising of European (white) superiority over Indigenous peoples?

Or the product of a sincere if misguided goal to achieve eventual equality through assimilation—a policy of assimilation that required firm administration?

Or—?

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.