From Dust to Dust: The Story of Wahlachin

Communities—villages, towns, sometimes even cities—can come and go. Then we call them ghost towns.

British Columbia has had its share—100s of them, in fact. That said, hands up Chronicles readers who can name, say, six of them. Two? One?

Of the province’s many lost communities, two have achieved legendary even mythic status: Phoenix, which, unlike its namesake, never did rise from the ashes, and Wahlachin.

Phoenix, because, unlike most of the province’s here today, gone tomorrow communities, it was, if ever so briefly, in every sense of the word—size, population and infrastructure—a city.

Wahlachin, because it was built upon, of all things, a dream. It literally defied commonsense and paid dearly when changing circumstances and harsh reality finally kicked in.

* * * * *

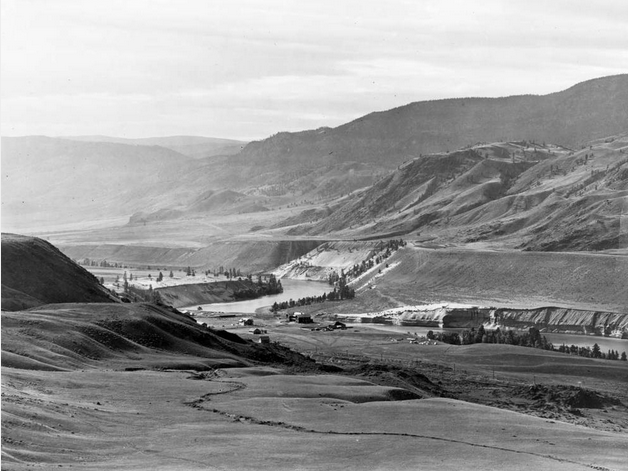

The Thompson River Valley.—BC Archives

As noted, Walhlachin, today an unincorporated community 17 miles east of Cache Creek, isn't the only ghost town B.C. has produced over the years. But it is unique, and one whose story, though often told, continues to intrigue. The puzzle is there today for all to see: why would anyone have attempted to transform this semi-desert land, high above the Thompson River, into a productive oasis? Not that it was impossible, just, well, strange.

American engineer and ‘father’ of Wahlachin, Charles E. Barnes. —BC Archives

Since 1870, with the exception of a two-acre apple orchard, Charles Pennie had successfully grazed cattle on this bench land. But, by the turn of the century, 30 years of foraging had stripped the resident bunchgrass, leaving mostly sage brush and cactus. Pennie’s solution was to irrigate 40 acres of hay with water drawn from Brassy Creek. Upon his death in 1900, the Pennie ranch went on the market.

Charles E. Barnes, an American engineer working as a surveyor in Ashcroft, was struck by the late rancher’s success at nurturing a healthy orchard by means of irrigation. In his mind he could see lush orchards and vegetable gardens growing in this eastern limit of the Semlin Valley. All that was needed was more water drawn by means of another, miles-long irrigation flume.

In 1908, an inspired Barnes persuaded the British Columbia Development Association (BCDA) to buy the Pennie ranch and an adjoining 380 hectares (930) acres. The purchase price of just over a quarter of a million dollars (about $7.7 million today) included all livestock which was sold off to free the land for farming.

Two subsidiaries of the BCDA, the (presciently if unwittingly named) Dry Belt Settlement Utilities, and the B.C. Horticultural Estates were incorporated; the former to create a 25-acre townsite, the latter to market the surrounding land for farming. Work quickly commenced with the construction of a hotel, general store, bunkhouse for construction workers, and the first private residences.

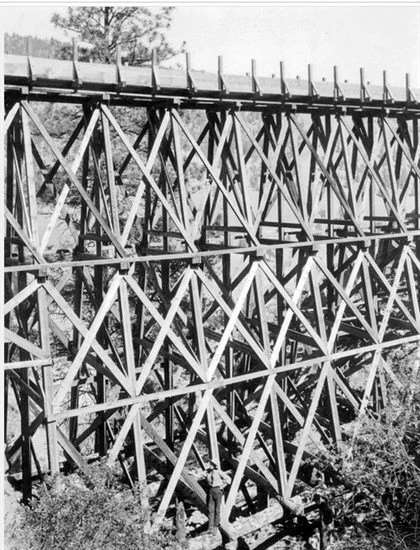

An elaborate and expensive flume system was constructed to carry water all of 20 miles to the arid soils of Wahlachin. —BC Archives

A dam at Deadman Lake, on the north shore of the Thompson, fed the Snohoosh flume, a gravity-fed chain of ditches and flumes 20 miles long that was the linchpin to Barnes’s grand scheme. The ambitious project involved an elaborate system of six-foot-wide ditches and trestle flumes over hill and dale. Upon completion, it was justly advertised as one of the finest waterworks systems in the province.

Clearing the land and beginning construction of Wahlachin townsite. —BC Archives

The first apple trees were planted in the spring of 1909 and solid cottages of frame and stone construction were built for sale to the upper-class clientele whom BCDE proponents hoped would buy five- and 10-acre farmsteads.

Planted land was priced at $350 per acre, raw land sold for $300 per acre. Water, lifeblood of the fledgling fledgling community, was a gift: only $4 per acre per year.

A large community hall (complete with grand piano, spring-loaded dance floor and steam heating) was built, as well as a polo field, swimming pool and (depending upon the season) skating rink. A golf course was never completed. The “commodious” two-storey, gabled Wahlachin Hotel completed the instant town’s amenities and set the tone (suit and tie were mandatory) with its liveried attendants, plush accommodations and decor. No less a personage than Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier performed the ribbon-cutting ceremony for its grand opening in 1910.

The Wahlachin Hotel was strictly high-class—no suit, no tie, no entry. —BC Archives

For those of Wahlachin's new residents (many of them retired army officers) who could afford butlers, maids and field hands, it was a good life.

Those not so blessed financially had to work, and work hard, to tame the parched ground even with piped-in water. Few had previous farming experience, most being the second and third sons of wealthy Britons whose eldest brothers had creamed the family inheritance as per the custom of the day. Some, no doubt, were what was known disparagingly by locals as “remittance men”—often black sheep who were paid an allowance by their families to immigrate to the colonies and to stay there.

Encouraged by land sales promoted by its airy promises of life as a gentleman farmer, the BCDA bought more another 3265 acres (1321 hectares) from the provincial government. By 1911 Wahlachin had a town hall, a bakery, barber, butcher, dairy, livery stable, ladies fashion store, two insurance offices, three laundries, its own (albeit shortlived—just three editions) newspaper, the Chronicle, and a temporary school (made official two years later).

Left: This steam-powered tractor was high-tech at that time. Right: irrigating a crop of onions. —BC Archives

Earlier, the community had achieved its first small harvest of fruits and vegetables such as onions and potatoes having provided fresh table produce and, likely, some cash flow. Existing photographs of Wahlachin farming operations show soil that looks dusty-dry, but the apple trees appear to be healthy, the onion fields full, and a shovelful of seven potatoes weighed all of 12 pounds.

(Not surprisingly, the very British-looking farmer posing with the potatoes is wearing a suit and tie. No wonder that Wahlachin was regarded, not without sarcasm, by its more earthly neighbours as Little England.)

Wahlachina farmers even grew their own tobacco. —BC Archives

In anticipation of future harvests, the development company built a packing house. But all of this development had cost a fortune, more apparently, than had been taken in through its realty sales. The BCDA’s debenture holders, most of them in the Old Country, grew impatient then forced the company into liquidation. Investors finally settled for four cents on the dollar.

That’s when the Marquess of Anglesey came to the faltering community’s rescue, buying a minority share in the restructured BCDA and, throwing good money after bad, laid out a second townsite. Ironically, he, a noble by birth, brought a more egalitarian approach to Wahlachin—mere mortals could now use the hotel (whether they still had to wear a tie isn’t mentioned).

By 1914, Wahlachin had a population of 150 and was producing small crops of apples and vegetables. But—on August 4, 1914, Great Britain went to war with Germany.

Suddenly, all their labours and Investments meant nothing to the patriotic British citizens of Wahlachin. Of a population of 107 eligible men, 97 enlisted for active service. Gordon Flowerdew, as a lieutenant in the Lord Strathcona’s Horse, would earn the Victoria Cross posthumously.*

Those left to hold the fort had to carry on with lack of leadership, reduced financial resources, estrangement from the ‘locals’ (Canadians and Indigenous) and an increasing battle against the forces of nature after spring rains damaged the miles of Snohoosh flumes and ditches.

The fatal blow came in 1918 when a rainstorm severed the lifeline altogether and hard-won cropland swiftly began to return to the sagebrush of old.

The ruined Marquess of Anglesey, by then the major shareholder, tried unsuccessfully to persuade the provincial government to buy his estate for returned servicemen. A postwar slump in the produce market completed the tragedy of the model farming community. Only four years later, Wahlachin was all but abandoned to the desert. Ironically, only the Pennie ranch survived.

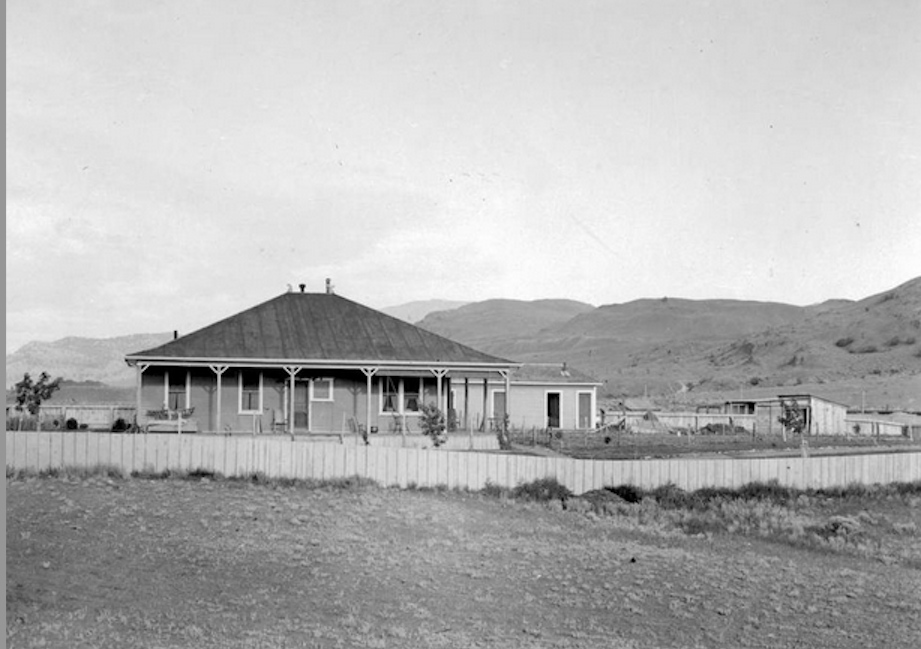

Some of the original “ranch houses” still survive at Wahlachin. —BC Archives

When all was said and done, Wahlachin’s return to arid nothingness (a small residential community and some of the original “ranch” houses still exist) shouldn't have come as a surprise to anyone. What had originally been known as Pennies, for the pioneering cattle rancher, was first renamed Sunnymede.

Then enterprising development company copywriters translated the local Skeetchchestn Band name, “Walhassen," as meaning, “abundance of the earth,” or “bountiful valley.”

Walhassen actually means, “land of round rocks".

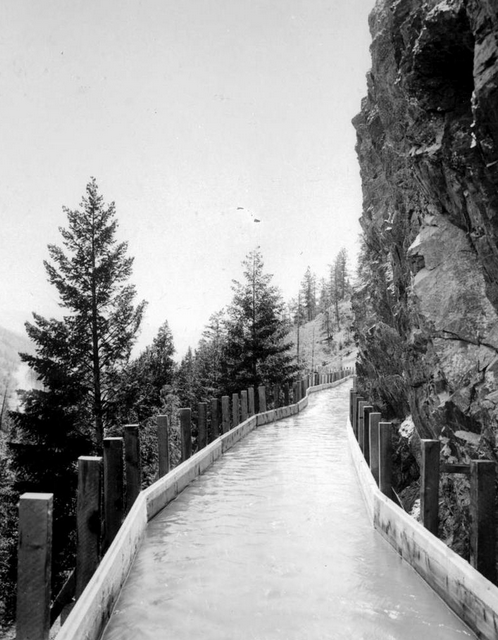

A section of the long abandoned Wahlachin flume as it appeared in 1977. —BC Archives

* * * * *

*Gordon M. Flowerdew rose from a private in 1914 to, by March 1918, a commissioned officer in command of C Squadron of Lord Strathcona’s Horse. This was, of all things in the horrors of First World War trench warfare, a cavalry unit in France. What has entered the records as the battle of Moreuil Wood and “the last great cavalry charge” was also Flowerdew’s last as he, and half of his men, were mortally wounded.

But this replay of the Charge of the Last Brigade had its desired effect, blunting an advance by five infantry companies and an artillery battery.

Gordon Muriel Flowerdew, as his name almost suggests, was described as “not robust.” That didn’t stop him from winning the VC. —Canada Dept. National Defence, WW1 Collection

The former Wahlachin farmer’s citation for the Victoria Cross, Great Britain’s highest award for valour, reads: “For most conspicuous bravery and dash when in command of a squadron detailed for special services of a very important nature. On reaching his first objective, Lieutenant Flowerdew saw two lines of enemy, each about sixty strong, with machine guns in the centre and flanks; one line being about two hundred yards behind the other.

“Realizing the critical nature of the operation and how much depended on it, Lieut. Flowerdew ordered a troop under Lieut. Harvey, VC, to dismount and carry out a special movement, while he led the remaining three troops to the charge. The squadron (less one troop) passed over both lines, killing many of the enemy with the sword; and wheeling about galloping on them again.

“Although the squadron had then lost about 70 per cent of its members, killed and wounded from rifle and machine gun fire directed on it from the front and both flanks, the enemy broke and retired. The survivors of the squadron then established themselves in a position where they were joined, after much hand-to-hand fighting, by Lieut. Harvey's part.

“Lieut. Flowerdew was dangerously wounded through both thighs during the operation, but continued to cheer his men. There can be no doubt that this officer's great valour was the prime factor in the capture of the position."