Who Shot Victoria Police Constable Alex. Smith?

What a way to start the new year of 1896. City Constable Alex Smith was at death’s door. Shot in the chest, he’d been rushed to Royal Jubilee Hospital where doctors announced that they could do little for him.

If Constable Smith died, his would be the third death in the line of duty for the Victoria Police Dept. —BC Archives

The bullet was lodged in his lung, surgery would kill him, and it was but a matter of time before he succumbed to hemorrhaging, blood poisoning or pneumonia.

As he lay dying, fellow officers of the Victoria Police Department realized they had a mystery on their hands.

* * * * *

Assigned to night duty, Smith had been in the habit of dropping into his home on Michigan Street for a midnight ‘luncheon’. At that hour, on the night of Dec. 30th, he reached home on schedule—only to startle his wife by staggering through the back door and gasping that he’d been shot.

When the city medical health officer, Dr. Fraser, arrived and examined the injured constable, he pronounced the wound to be fatal. Consequently, Fraser deemed at advisable to secure a deposition and he sent for Police Magistrate Macrae. According to Smith, he’d entered his backyard as usual, when a shot was fired from the corner of his woodshed. As the pistol ball lodged in his breast, his unknown assailant leaped over the fence and vanished.

Despite the seriousness of his wound, Smith said he managed to draw his revolver and fire a single shot at his assassin before he stumbled in his back door.

Curiously, Smith's wounding marked the fifth year's-end in a row that Victoria had been saddened by similar tragedy: “By strange coincidence, or as the superstitious might agree, by fateful influence, " commented the Colonist, “the last day of each year sees in Victoria some suicidal tragedy. So it has been for the past five years, and yesterday proved no exception to the remarkable rule, the early morning hours witnessing not one but two ghastly shooting affairs...”

The second “suicidal tragedy”—the Colonist had obviously reached its own conclusion as to Const. Smith’s wounding—was that of a man named Griffith who’d last been seen alive when he returned to his hotel at 3:00 in the afternoon, his body being found the next day by a houseboy.

By the time the morning daily went to press, Smith was reported to be “waiting for death” in a Jubilee Hospital ward, the surgeons having agreed that his recovery was possible but not at all probable.

As for the true facts of the case—attempted murder by a " cowardly enemy,” or attempted suicide—the police were inclined to believe the Smith had shot himself.

“Those who believe Smith was a victim of a revengeful murderous enemy, base their opinion upon the account of the shooting given by the wounded officer himself, in an anti-mortem deposition taken by Magistrate Macrae; those who incline to the self-murder theory—among them Chief Sheppard and the majority of his men—prefer the silent testimony of circumstances to the statement of the injured man.”

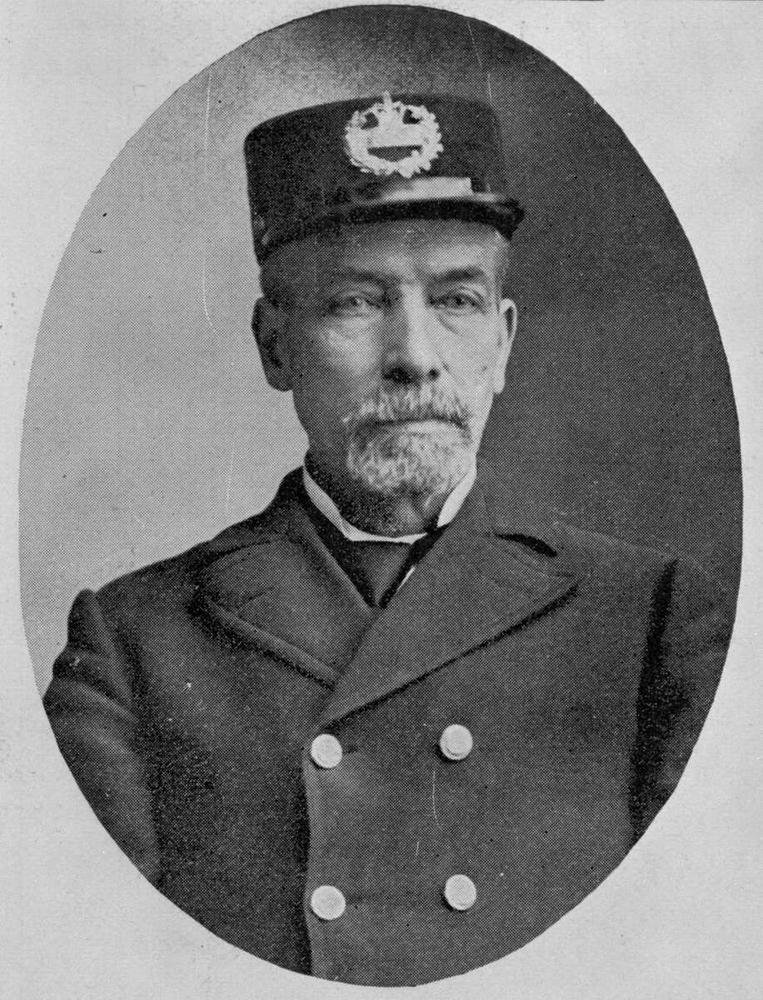

Almost from the start, VPD Chief Harry Sheppard doubted Smith’s story of an assassin. —BC Archives

Investigating officers had found a pool of blood in Smith's woodshed, but little elsewhere. This, and other circumstances, led them to suspect that, rather than having been shot by someone else, he’d actually shot himself with his service revolver. By the amount of blood on the floor of the woodshed, they considered it likely that he remained there for some time before stumbling to the house.

Bolstering this theory was Smith's own conduct in recent weeks, the Constable having been called before the chief on more than one occasion for his heavy drinking. In fact, he’d been threatened with suspension by Chief Sheppard the day he was shot. When newspaper reporters attempted to confirm this angle, they were told that Sheppard was ill and unavailable for comment.

A Scotsman by birth, aged about 35 years, and a member of the city force for several years, Smith was described as being a “quiet, unassuming” man who had no known enemies.

That same morning, police had a second shooting on their hands, the body of prospector John W. Griffith having been found in his room in the Occidental Hotel. This time, there was little mystery, Griffith having left a disjointed note for his wife in Port Townsend before ending his life by placing a .38 revolver to his right temple.

Victoria’s Occidental Hotel where, at year-end 1896, the body of John Griffith was found in his room. This time, there was no mystery as to the identity of the shooter. —BC Archives

The only question concerning Griffiths’ suicide was why he’d taken his life. He’d but recently returned to Victoria from the west coast of the island, during which time he’d reportedly “located more promising mineral claims. The day before, he’d testified before the Pelagic Sealing Commission “as to the value of the machinery in the seized [sealing] schooners. He was apparently in his usual jovial mood and no one had suspected that he intended to take his own life.”

“It is true,” a Times reporter observed, “the world had not treated him as well during the last couple of years as he was used to, but he took his reverses philosophically and was enthusiastic over the prospects of doing well with his claims.”

Written on pages torn from a notebook, the letter to his wife mentioned that Griffith had feared that he was losing his sanity and that he knew he was going to die shortly.

Well-known and popular throughout the Pacific Northwest, Griffith’s suicide stunned his friends and acquaintances. Twenty years before, he’d been employed in the office of the Albion Iron Works. Then he’d served as bookkeeper for Messrs. Goodacre and Dooley before moving to Port Townsend to take a similar position. At one time he’d owned considerable property, only to lose it all during an economic slump.

“Since then he has held several positions, but laterally had spent considerable time in the mountains, and it is possible that into this lonely life to which he was not used, can be assigned the aberration which led to his act.”

As for the Const. Smith shooting, it was then reported that the “first information that a tragedy had been enacted at the Smiths’ “cosy home on Michigan Street” had been given by a Colonist printer. While passing the Smith house as he walked home from work at 3:00 in the morning, the printer heard Mrs. Smith weeping hysterically and investigated. When he saw the cause of her alarm, he hurried to the nearest telephone.

Curiously, his first duty seems to have been to his newspaper as two Colonist reporters reached the scene quite some time ahead of Dr. Fraser and police.

By then, the reporters had interviewed the wounded Smith, who hadn’t lost consciousness. He’d returned home for “lunch,” he said, and had made it to his back door—in fact, he had his hand on the knob and was in the act of turning it—when, without a word of warning, someone fired at him from a few feet away.

Turning, Smith's recounted, he saw and recognized his assailant, who, he believed, had waited in ambush for him, having been familiar with the Constable's routine. Struck in the chest by the first shot, Smith saw that the assassin was about to fire a second time; with his remaining strength, he fell inside the house, locked the door and warned his wife not to venture outside. He then removed his bloodied coat and vest and lay down upon the bed.

Throughout the interview, Smith, who didn’t seem to be in great pain, hadn’t expressed much interest in the gravity of his wound or in the apprehension of his assailant.

Rather, he gave the impression that he was totally unconcerned by it all. When repeatedly asked who’d shot him, he replied, “Oh, I know who it was. It's not the first time he's laid for me, and I'll get even with him, all right, if I get over this. I'm not going to give his name till I can get after him myself, though, if I am done for, Walker knows him—it's a friend of his.”

Although he claimed to have been shot as he turned the knob of his back door, the bullet had entered his chest just above the heart rather than his back. When asked if he’d been able to return the shot, he hesitated, then answered, “No, I've lost my gun.”

When Const. Allen searched Smith's woodshed, he found the missing revolver hidden behind a pile of wood. One shot had been fired and it was apparently of the same calibre as that which caused the wound in Smith’s chest. Examination of the injured man's coat revealed powder burns near the area of the heart. Chief Sheppard considered it likely that Smith had been aiming for his heart and would have been successful had not the bullet been deflected into his lungs by a rib.

Dr. Fraser's examination “found the injury to consist of a dangerous penetrating chest wound on the left side in the region of the heart.

“From the location of the point of entrance it would seem most likely that the bullet would pass through the body. It had found no exit, however, and it's still lodged in such manner that probing for it would only seal the fate of the patient..." and the doctors could only wait for death to result from pneumonia, hemorrhage or, as was most likely, blood poisoning.

All of these factors, circumstantial though they were, were sufficient for Chief Sheppard to close the case as one of attempted suicide. The powder-burned coat, a pool of blood in the woodshed and nowhere else, “the fact that Smith had no enemy but himself and his appetite," convinced the chief that there’d been no assassin.

He also pointed to the inconsistencies in Smith's deposition to Magistrate Macrae: “He saw the assassin, he said, but could not describe him; the shot was fired while he was going from the house to the [water] closet, which is off from the woodshed; he returned the fire and lost possession of his own revolver, he didn't know how; the man who shot him stood eight or 10 feet away, and though he could see the bright barrel of his weapon he could not see his face..."

Added to the fact that Smith had been depressed after being warned of suspension, thought Sheppard, could be “establish[ed] a complete and commonsense presentation of the case".

Two days later, a coroner's jury ruled suicide in the death of John W. Griffith, and Const. Smith remained in hospital where he was said to be resting comfortably and—possibly on the road to recovery. Although there was no hope of removing the bullet, and he remained in serious condition, his doctors now thought it just possible that he could survive indefinitely.

Three days later, however, although his condition remained the same, the physicians were again of the opinion that he couldn’t live “save by a miracle”.

Then Victoria suffered another tragedy when a former resident, Edith Dwelly, was found dead in her Chelsea, England home. Two months earlier, Miss Dwelley, who’d been residing with her grandmother in Victoria Vest, had been pulled unconscious from Selkirk Water. As she was clad in her nightgown, it was charitably surmised that she’d fallen into the water while sleepwalking.

Those closer to her considered it a suicide attempt, as Miss Dwelley was pining for a young man who hadn’t returned her affection and she’d repeatedly talked of ending at all.

However, after her rescue she’d seemed to recover and, in due course, was sent home to her parents. There, she made no mention of her ill-fated love affair and, other than acting in a subdued manner, gave no sign that she yet contemplated self-destruction. Then her mother found her dead in her bed, an empty bottle of carbolic acid and a death note on her dresser.

It was, sighed the Colonist, an old, old story.

Const. Alex Smith again made the news when his James Bay home was burglarized while his wife was visiting him in the hospital. Apparently, Mrs. Smith had disturbed the intruder upon her return as, although some items, including her cloak, had been taken. Other articles which had been packed for removal were left.

“If he continues to improve as rapidly as he has during the past few days," it was reported on January 14th, “Police Constable Alex. Smith will have the supreme satisfaction of disappointing death and the doctors and of being able to start upon the trail of his enemy in the near future—for he still denies that the injuries which sent him to the hospital on the last day of the old year were self-inflicted.

“Should he recover, as it is now altogether probable he will, the case will be a unique one from the surgeon’s standpoint, the cure having been accomplished by nature practically unaided. The bullet is still somewhere in Smith's body and likely to remain there. It occasions him but little pain or inconvenience, however.”

By January 19th, Smith was looking forward to being released from hospital. He continued to claim that he was shot by an enemy lying in wait for him at his home. Finally, on January 22nd, some three weeks after doctors had pronounced him to be beyond recovery, with the bullet still lodged within his body—but “as good as 20 men yet”—Smith was sent home. Although pale and drawn, he was said to be on the road to full recovery.

And he persisted in sticking to the story he'd given Colonist reporters before police and Dr. Fraser reached the scene: that his “would-be murderer had been prowling about the premises nightly for some time previous to the eventful December 30, greatly alarming his wife and causing her to complain to him that she was afraid to remain in the home at night.

“He is firmly convinced that it was the same desperate but unidentified enemy who succeeded in breaking into his house while he was an inmate at the hospital and his wife was in attendance there upon him."

And on this inconclusive note, alas, the shooting of Const. Alexander Smith ends. Curiously, his steadfast denials of attempted suicide, and the burgling of his home, had convinced some of his fellow officers who’d been so confident that the wound was self-inflicted, that “there may be some truth in Alec’s story after all”.

But, in the words of the Victoria Police Department, it was up to Smith to “tell all he knows about this enemy of his and why he is so vindictive,” before they could treat his case as one of attempted murder.

* * * * *

The 167-year-old Victoria Police Department lists six “fallen heroes,” officers who were killed in the line of duty, or who died as a result of injuries sustained while on duty. Even if he hadn’t survived his wound, Const. Alex. Smith likely wouldn’t have been one of them.