Zeballos Streets Really Were Paved With Gold

Last year, when telling the saga of the Leech River gold rush of 1864, I referred to it as Vancouver Island’s only real gold rush.

By that I meant gold rush in the generally accepted sense of a wild stampede of fortune seekers converging in a frenzy and from all directions upon some promised El Dorado.

Like the Fraser River and Cariboo gold rushes, for example.

‘Downtown’ Zeballos with its plank main street in the 1930s. —BC Archives

Certainly, the Island’s west coast Zeballos excitement of the late 1930s had most of the ingredients of a rush, a stampede. The biggest difference was that, unlike the Leech and Fraser rivers and the Cariboo, which were placer mining (panning, sluicing, dredging gold from rivers and alluvial gravels), Zeballos required hard rock mining—drilling, blasting and tunnelling into solid mountainsides.

This, of course, cost money. It required manpower and expensive materials that exceeded the skills and pocketbooks of the classic lone prospector with his gold pan and burro.

But it was exciting, all the same.

* * * * *

Talk about coincidence!

Before returning to work on this week’s Chronicle I received this notice from historian, author and friend Daniel Marshall: “CALLING ALL HISTORY SLEUTHS! The mystery of the SPANISH CANNON AT KYUQUOT -- I have been searching for further information on two 1910s photographs held by the British Columbia Archives that suggest a Spanish Cannon and Bell were once located at the Indigenous village of Kyuquot on the West Coast of Vancouver Island.

“Where are these two historical curiosities today, and I wonder if they were ever positively identified? Have a Look!”

The ‘Spanish’ cannon and bell at Kyuquot. —BC Archives

One comment identified the ‘cannon’ as a 19th century cannonade, likely of American origin, and questioned why the bell couldn’t be from a church. (Or from, as is more likely the case, say I, one of the many steamships that were lost in these waters long known as the ‘Graveyard of the Pacific’?)

The answer, I believe, is sheer wishful thinking. There’s a popular mystique to Spanish exploration of the B.C. coast in the 18th century.

Why? Because of their documented record of wholesale slaughter and enslavement of the Inca and Aztec peoples for their gold in Central and South America. Consequently, almost every abandoned mine shaft within reach of salt water along the west coast of Vancouver Island has come to be linked, if only in the imagination, to Spanish gold mining activity. Simply because (so I surmise) it’s much more romantic than is its more likely pedigree—just another abandoned copper or iron mine test-hole or shaft from the 18-1900s.

I say this, you realize, as a professional storyteller. While I strive for historical fact, it’s the story that makes it worth the exercise, and I’ve eagerly pursued the Spanish angle since my teens. Stories like the fabled lost steps in the Leech River area, supposedly carved by Spanish mining for gold. The lost ‘Spanish’ cannon in nearby Jordan Meadows. Conquistador slavers overthrown and killed by local Salish people. The tidal cave in isolated Cape Cook area that’s said to contain 30-odd skeletons encased in rusted armour.

And on and on... Great stories, yes! but, sorry, folks, pretty much myth.

Note that I say, they’re probably myth. In a previous telling of this tale, in my coming-up-to-almost-half-a-century-in-continuous-print book, Ghost Town Trails of Vancouver Island (Heritage House Publishing), I referenced the late historian B.A. McKelvie who, long before I hit the scene, wrote about Spanish activity along the Island’s west coast.

McKelvie noted that Spanish archives contain reference to a single shipment of gold from Vancouver Island worth three quarters of a million dollars. Did he mean its value at the time or, inflation added, when he wrote his story?

Whatever the case, McKelvie was more specific in describing the Spaniards’ gold as being “mostly—if not all—from placer workings. There are evidences, however, that they did some lode mining. They certainly believed that there was ‘gold in them thar hills,’ and they dreamed of the day when the mountain masses would be mined and yellow ingots would be shipped from the West Coast.”

However, after an international incident that almost led to war, Spain ceded all claims to the Pacific Northwest to the British. That was the end of their exploration and development activity here.

Which brings us in a roundabout way to today’s post on the Zeballos gold excitement of the 1930s.

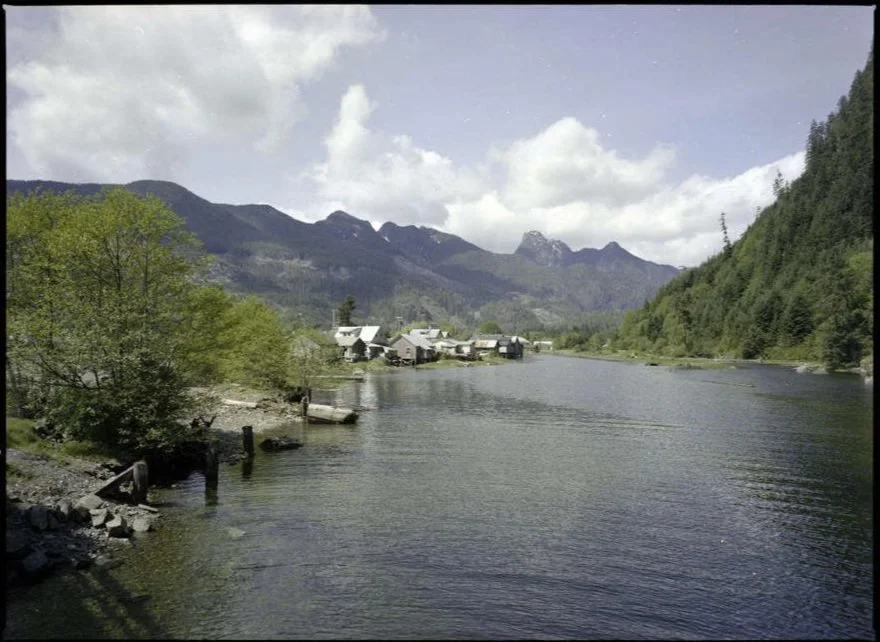

With the gold excitement of the 1930s and 1940s long past, Zebellos returned to being a quiet logging and fishing community, as shown here in 1979. —BC Archives

It should be pointed out that Zeballos, in the lee of Nootka Island, is a corrupted tribute to Spanish naval lieutenant Ciriaco de Cevallos who explored these waters more than 200 years ago, at a time when competing British and American explorers saw more tangible value in sea otter pelts than in searching for will-o-the-wisp gold mines.

* * * * *

The prospects of finding gold on the Island’s west coast after the Spaniards’ departure were all but forgotten over the decades, overshadowed by a chaotic rush to the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii) in the early 1850s, followed by stampedes to mainland B.C.’s Fraser River, Cariboo, Big Bend, Omineca, Atlin and a host of other, smaller strikes.

As prospectors began to pour in, the tiny fishing village of Zeballos, shown here as it was in 1937, began to grow until it had 1500 residents. —BC Archives

T.J. Marks was one of the first to prospect this region in 1907, but it wasn’t until after the First World War that a handful of prospectors began to really probe the mountains and fjords which form the Island’s west coast. It was these unsung heroes who, according to McKelvie,“found some very rich gold specimens from the Cape Cook area” and recovered placer gold from a creek “somewhere between Cape cook and Kyuquot Sound”.

Their belated discoveries drew attention to landlocked Zeballos, 200 nautical miles northwest of Victoria, then accessible only by sea and air.

First to be staked within a mile and a half of tidewater on the Zeballos River was the Tagore Group in 1924. But these claims got off to a slow start. Over five years a succession of owners were stymied by periodic flooding. Finally, discouraged, despite a promising shipment in 1929 of two tons of high-grade ore (the first gold to be shipped from Zeballos), they switched their attention to the nearby King Midas property.

More years of mining activity but no earthshaking success by various parties followed. By then it was mid-Great Depression, a time when the dream of finding gold held even more allure for those willing and able to walk the talk. What would become the richest of the Zeballos gold properties, the Privateer Mine, joined the fray in 1936 when a Victoria syndicate of seven Victoria men incorporated Nootka-Zeballos Gold Mines Ltd.In 1936, living in tents in a canyon above Spud Creek, four miles from tidewater, partners Ray Pitre, Herb Pevis, Chester Canning and John Frumento bored into the hillside in almost constantly miserable weather. With little money and with everything—food, materials and machinery—having to be packed in from the beach on their backs or by horses, they innovated and jury-rigged as necessary with salvaged materials.

All the while, Victoria partner and lawyer David S. Tate worked every angle to raise money so they could carry on the work. But investment dollars were scarce in the Dirty ‘30s and finally, in desperation, Tate and his law partner Percy Marchant risked $25,000 on their own securities.

The entrance to Privateer Mine. —BC Archives

To paraphrase myself in Ghost Town Trails of Vancouver Island and friend McKelvie, “At the mine, winter had finally slowed development to a crawl and it wasn’t until March 1938 that the partners made their first shipment of ore. Although a ‘mere’ 4800 pounds, it represented a massive challenge in itself, having to be taken to the beach through a rugged almost impossible country. Pitre and his little crew," McKelvie continued, "determined to get it out, for the smelter returns were necessary to keep operations going.

“It was a terrible task. Those who took part in that work still shudder at the remembrance of it. The ore was sacked and was carried on the backs of the men down the narrow, slippery trail, through the mud and over the windfalls to Zeballos River”.

Think about that: 4800 pounds of ore—rocks!—is almost two and one-half tons, sacked and hauled on men’s backs, up, down and along winding, slippery wilderness trails for four miles. How many trips did it take them? (Editor: I once backpacked sacks of Portland cement up a steep hillside—another story—for a fraction of that distance, so I have a slight sense of what they faced. Talk about determination!)

Far from tidewater, a small community sprang up around the Privateer Mine. —BC Archives

Their herculean efforts paid for further development of the mine and, by late 1937, shipments to the Tacoma smelter totalled $118,000. The following year, they took out $200,000 and what was now known as the Privateer Mine was attracting national attention. An agreement with a large eastern mining firm to build a 75-ton cyanide mill and powerhouse soon followed.

Making all this possible was the fact that the gold was plentiful and high-grade—up to 45 ounces to the ton. Already, the ‘wonder mine’s’ owners were predicting three years’ reserves worth an estimated $3 million dollars—big money in the Depression years.

By this time, of course, the region was crawling with prospectors, many of them freelance but also many in the pay of large, international mining companies. This was hardly surprising, given that "Some of the [Pioneer Mine] ore was so rich," in the words of one professional miner, "they shipped it to the smelter in carbide tins and [the Tacoma smelter] said it was the richest ore and most extensively impregnated with free gold that they had ever received”.

Interest was fanned even more when the Privateer staged a public pouring of the first gold bricks at its newly completed mill.

Proof of the pudding for the Privateer Mine was its first pouring of gold ingots. —BC Archives

But the Pioneer Mine wasn’t the only new kid on the block. Despite heavy snows through the winter of 1937-38, the Spud Valley Mine was also spewing forth rich returns. It was so rich, in fact, that mine official A.B. Trites could brag that, instead of hand-picking the ore from the waste in the usual manner, it was easier to extract the waste from the ore.

At the headwaters of Alice Arm and connected to tidewater by a newly-built road, the Golden Gate Mine was yielding between $6 and $232 to the ton.

“Other properties such as the North Star group, Ray Ore, White Star, Zeballos Gold Peak, and Central Zeballos, offered equally optimistic reports,” I wrote in Ghost Town Trails. But the Privateer remained the star player. A single, foot-wide “slab” of high-grade ore assayed at 30 ounces to the ton.

By this time, too, promising prospects had been staked out on the Little Zeballos River, as far as Kyuquot Sound to the northwest and Tahsis Basin to the southeast. In a special edition, the Western Canada Mining News predicted 100s of men would soon be exploring the Island from Port Alberni to Quatsino Sound. The News advised prospectors to carry their gold pans: “Small creeks should be tested carefully and creeks yielding colour should be examined and traced with the view of defining bedrock in the creek and among the valley walls.”

With the exception of the Golden Gate Mine, which was blessed with a truck road to tidewater, all of the mines and prospects in the Zeballos area were cursed by their isolation. Zeballos itself remained inaccessible to the outside world except by ship or plane. Once a man landed on the beach, he was pretty much on his own. Trails were so bad that, reminiscent of the famous Chilkoot Pass of the Klondike gold rush, he could only hope to make two trips a day with 50 pounds on his back each trip.

All ore had to be taken out the same way, which explains the use of carbide tins for containers—they were slightly bigger than a gallon buck of ice cream.

And God help a man if he were injured. Prospectors John Hagno and Inar Aston learned this the hard way when, high up in glacier country, Aston slipped into a crevice and broke his leg. Hagno had to back-pack his 200-pound partner to the beach, 12 miles distant!

Besides the lack of roads, miners had to contend with rain and snow for months on end. Rain swelled rivers and creeks and snow all but halted above-ground activity. Despite these obstacles, in just over a year, ‘downtown’ Zeballos (all of one street which was usually knee-deep in mud) had experienced “the swift march of civilization: fine hotels, well-stocked stores, bank, electrically lighted buildings, school, progressive newspaper, its library, board of trade, hospital...”

Not mentioned in this glowing account of progress was another new town asset, its brothel.

Zeballos, 1947, after the party was over.—BC Archives

At its peak, Zeballos had 1500 residents—a far cry from its commercial fishing population of the 1920s. The outbreak of the Second World War all but brought mining activity to a halt for the duration. But even the return of peacetime couldn’t compensate for the price of gold being fixed at $35 an ounce and few of the mines resumed full or extended operation. In the 1960s, a short-term iron mine and logging became the new currency of Zeballos residents which today, thanks to finally being linked to the rest of the Island by road, is a destination for tourists, kayakers, spelunkers and sports fishermen.

And, of course, an occasional prospector.

* * * * *

My headline, “Zeballos streets really were paved with gold,” is the literal truth. Years after roads opened up the interior, it occurred to someone that the onetime streets of mud had been replaced with ore waste—rocks and gravel that perhaps hadn’t been thoroughly sieved of their gold particles. A minor rush was soon on as residents proceeded to mine the streets for any overlooked ore.

* * * * *

One of the few recorded losers in all the Zeballos excitement was miner Conrad Wolfe who acquired the Tagore property in 1932. Assays indicated up to 22 ounces of gold to the ton but Wolfe, like previous owners, was stymied by the ever-present danger of flooding from the Zeballos River. He’d just begun a second shaft on higher ground when he was called away on urgent business. After taking the precaution of back-filling his new shaft, he headed out, only to be detained. His claim lapsed and by the time he returned to Zeballos, the Tagore was under new management.