‘A Great Yarn of Old East Kootenay’

“Mr. President: It is with much diffidence that after repeated urging on your part I undertook to contribute a paper to this society...”

So began, modestly, George Hope Johnston’s address to the Calgary Historical Society in February 1920.

George Hope Johnston’s headstone. —findagrave.com

But he wasn’t there to reminisce about Prairie history. He was there to talk about, in the words of a Calgary Herald reporter, the “wild old days” of 1880s East Kootenay, B.C.

Johnston’s recollections, repeated verbatim in the newspaper, the reporter assured readers, would interest all who read them.

As, I’m sure, they’re going to interest Chronicles readers.

* * * * *

Early Days in East Kootenay Told Over Chasm of 40 years; Old Timer Looks Back Into Pass with Feeling Akin to Regret.

_____________

(The vivid story contained in the paper read by George Hope Johnston before the Calgary Historical Society last week is one which will interest and amuse all who read it. Mr. Johnston knew the mountain west in the early ‘80s, and consequently came in close contact with all sorts and conditions of men. In the ebb and flow of the human tide which invaded the mountains and valleys, looking for wealth and adventure and to eke out a living, thousand are unknown today. Some rose to comparative fame, others went under or drifted back to the wider world from which they came. It is with this human element, the richest element in the world, that Mr. Johnston deals, and Herald readers will have much enjoyment reading his racy narrative.)

By G. Hope Johnston

MR. PRESIDENT: It was with much diffidence that after repeated urging on your part I undertook to contribute a paper to this society. Had it not been that the subject I chose was one with which I was very familiar, I am certain that I would never have found courage to try my ‘prentice hand. As it is, I would ask your Indulgence with a tyro in the art of writing anything for the public, when it must carry the signature of the author.

However, I do not believe that there is anyone alive today who knows more intimately than I the conditions prevailing in East Kootenay in 1883 and 1884, or who had a closer personal acquaintance with the men who lived there during those early days.

During the first 10 months of my stay in the district I crossed the main chain of the Rockies three times—once by the Crow, coming in; once by the Sinclair Pass, going to Calgary and returning, and in the early spring of 1884 going out by the Kicking Horse Pass, over the pack trail from Golden to Field. The wagon road had been completed from Laggan to that point in the fall of 1883. In the summer of 1884 I made a trip with a saddle and pack horse from Golden to the Kootenay River, near the point where it comes back into Canadian territory after swinging south into the States.

I went from that point by bark canoe 50 miles down the river to the mouth, and 50 miles up the lake to Pilot Bay, where the customs house had been established with Mr. Krykert in charge. I stayed there about three weeks, crossing and recrossing the lake and down to the present site of Nelson.

Yes, I think I knew that Kootenay Valley in 1883-1884.

In these recollections I have “nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice”. I have written those things only of which I have personal knowledge. While sensible that they can have little historical value, I trust that they may serve to entertain in a small way the members of this society. This paper I have entitled “East Kootenay in 1883-84”.

FIRST TRAVELLED THERE IN 1883

I first saw East Kootenay in the summer of 1883, going in through the Crow's Nest Pass in the month of July with Hon. F.W. Aylmer, whom I had known in Manitoba in 1880. He had assured me that there was a brilliant opening for cattle raising in the Columbia Valley, which explains my readiness to accompany him. This came to nothing.

Where there are now thousands of men from Michel, down the Elk River, up to Kootenay and down the Columbia to Golden, there were in the winter of 1883-84 about 25 white men and three white women.

In the late '60s there was a gold rush to Kootenay and 1000ss of prospectors swarmed all over the district. Large placer mines were worked on Wild Horse Creek, Bull River, Perry and Findlay creeks, and other streams, and large quantities of the precious metal were taken out. Wild Horse Creek must have been a bustling place in those days. The office of the gold commissioner, other provincial buildings and large stores were located there.

Miner Pete Lum works his hydraulic monitor on his Wild Horse Creek claim. —BC Archives

When I arrived considerable work was still being done, principally by Chinamen [sic] who bought water from a private company which had constructed a large ditch and plume, the intake being several miles up the creek. Much of the work was done in rewashing gravel which, in former years, had been treated by cruder methods, and I was informed that the Orientals [sic] still made very good wages, and something to spare after all expenses of operations were paid.

AN IRISH GENTLEMAN OF THE OLD SCHOOL

When I reached the place Wm. Fernie, the discoverer and locator of the coal seams at the place which afterwards received its name from the locator, was mining recorder, justice of the peace, peace officer and adjudicator on all questions relating to mining. He was an Englishman who had been, from his early youth, a prospector in many western mining camps. He was well-educated and more than competent to hold down such a position.

Coal discoverer William Fernie for whom Fernie, B.C. is named. —BC Archives

Owing to a change in the political colour of the local house Fernie was dismissed shortly after I came and replaced by a man named Kelly, who was as ignorant and inefficient and his predecessor was competent. Kelly held his position for only six or eight months, and was succeeded by Arthur Vowell, afterwards Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the province, with headquarters at Victoria.

Mr. Vowell came to British Columbia in 1862 and had experience in every branch of the government service. He was an Irish gentleman of the old school with whom no liberties could be taken but who dealt out evenhanded justice to all. A storekeeper, whose name I have forgotten, Dave and Mrs. Griffith, and a roustabout called Tommy Driscoll, were all the white people in Wild Horse Creek during that winter.

Dave Griffith was an original genius. A prospector by profession he was an amateur blacksmith and dentist (he extracted the wrong teeth, perfectly sound, from the mouth of the writer later on in the same winter), was one of the owners of the mining ditch, the revenue from which gave him a reasonable livelihood, and had never seen a railway until he was taken to Golden by J. H. Woods and Tom McVittle in the summer of 1883.

HANDED OUT WESTERN HOSPITALITY

Where now stands the thriving town of Cranbrook, John and Robert Galbraith had, during the early stages of the gold rush, located a store and also did a small amount of farming, irrigating the cultivated land with water from the nearby creek. Mr. and Mrs. John Galbraith kept open house and all comers were heartily welcomed. An offer of payment for his wholehearted hospitality would have given the old man an apoplectic fit as well as giving him the assurance, which with great candour he would have passed on to you, that you were an ignorant, under-bred Easterner.

Cranbrook now stands where the Galbraith brothers prospected and farmed. —cranbrooktourism.com

While absolutely honest in all his dealings he was famed as a narrator of tall yarns and would not have taken odds in that line from any of our experts in the Northwest. Another genius was old Norris, the customs agent, who, while possibly not as finished a disciple of Baron Munchausen, eked out with earnestness what he lacked in polish. It may have been professional jealousy, but there was no love lost between the two old gentlemen, each of whom was wont to characterize the other as a reborn Ananias (the biblical liar--TW).

Mrs. Galbraith was a kindly, whole-souled western woman, liked and respected by white, red and yellow...

Unlike the Herald, which gave almost a full page to Johnston’s talk to the historical society, I’m going to exercise editorial license for the sake of space limitations. —TW.

..Most of the supplies for the district were brought in by pack train to Joseph's Prairie from Bonners Ferry by the Galbraiths, and during the summers of 1883 and 1884 an extra train was put on to bring in supplies for the C.P.R survey parties [who], under Major Rogers, whose headquarters were at Golden, were locating the future C.P.R. line through the Selkirks.

A CPR construction crew pauses just long enough to have their picture taken. —BC Archives

During the fall of 1883 Wm. Fernie and his brother Pete located a ranch on Wolf Creek, about 16 miles due north of the present town of Fort Steele. I preempted close to where is now the small town of Windermere. The survey was made by Aylmer and was the first to be made in the district.

Needless to say, I located a choice piece of land and recorded a right to 250 miner’s inches of water, for irrigation purposes, on the adjoining creek...

A MERRY TIME HUNTING HORSE THIEVES

...I had been back only a couple of days when three prospectors, who had come in from Montana where they had been shooting buffalo during the construction of the Northern Pacific, came to our camp and informed Aylmer and myself that their horses with all their camp equipment and supplies had been stolen, and asked our help in following up the thieves.

They had trailed the thieves across the Columbia to a creek now known as Horsethief Creek. Of course, we went. Getting together a party, including old Tom Jones and Fred Wells, the latter of whom had come with me from Calgary, and taking two Indian trailers, Tatli, a Kootenay, and Pierre, second chief of the Shuswaps, we started at midday—with no blankets and only a lunch.

The tracking was bad and when the short October day was done we camped on a high bluff overlooking the creek without a fire—cold!

I shivered in my saddle blankets until I found a deep hollow, perfectly surrounded with thick spruce and lots of dry wood. Despite Aylmer's protests we soon had a fine fire going and put in the rest of the night in moderate comfort. In the morning the Indians were divided in opinion as to the track and we split into two parties. Jim Kane, one of the owners of the stolen horses, Fred Wells, Tatli and myself following up the creek.

About 11:00 we heard the sound of a shot and, spreading out as much as possible, went ahead. Shortly after, a man carrying a shotgun with a rifle slung across his back appeared. Covering him, I called to him to drop his gun. He did so and Kane, coming down the hillside, disarmed him. A few minutes later his partner, a young Swede, came up and he was also disarmed.

I don't remember ever being more hungry, and the badly cooked flapjacks and bacon which we forced one of the prisoners to cook from the stolen supplies were better than a banquet.

As the nearest magistrate was old Kelly at Wildhorse Creek, 75 miles away, we brought our prisoners before him. It was a clear case. The stolen property was identified and sworn to. No denial was made by the accused. But the old fellow refused to commit them for trial. Looking back now I don't know that I blame him so much. It was too late to send the prisoners out to Victoria; he would have had to act as jailer all winter; the horses and equipment were all recovered and no one was much the worse off. I was likely to be the only loser as I had paid all the bills.

We were furious then, however, and proceeded in a quiet way to cheer our spirits in the old, old way, which states back to Father Noah.

Late night evening I was talking to Old Tom Jones...[when] Wells came in hurriedly and said that Aylmer and Kane had got old Kelly and intended putting the old chap in the river. I ran toward the government offices and, sure enough, they had him. Kane was swearing by all that was holy that he would put old Kelly in the drink. Aylmer, who saw the thing as all a huge joke, was laughing immoderately. Telling him to go back to the [house], I tackled Jim Kane, who was just drunk enough to be obstinate.

Let the old chap go? No. He was going to put him in the creek.

“Jim," I said, “that is no good. The old fool ought to go in but then there might be a little trouble and he is not worth it. We will make a cage, put him in it, take him back with us to the lake and exhibit him.” Jim considered the proposal with drunken gravity and when I mentioned that there was still a bottle of whisky at the [house] he handed Kelly over on my promise that I would lock him up.

I had to keep my hands on him until inside the government buildings and then the old brute abused me like a pick-pocket. I'll never forget the figure of fun he made, sitting behind his desk with a muzzle-loading Colt revolver in each hand...

I reported the affair to the attorney-general A.E. Davie. Kelly was shortly after relieved of his duties and Vowell replaced him. I also was appointed justice of the peace for the district.

In those days in Kootenay one met men of many nationalities and of many different degrees in life. Some of them were cultured gentlemen who, even while roughing it, as all were compelled to do, endeavoured as far as possible to practise the decency and refinements in living, to which they had been accustomed from birth and by early training.

Occasionally, however, there would be one equally well-nurtured and well-bred, who, from some innate weakness [failed]...

For the most part, however, these men of Kootenay were strong. The west in the making has never favoured weaklings and these, whether physically or morally weak, went speedily under or left the country, the hardships of which they could not or would not endure.

Most of the men whom I knew one in those early days are gone, but their personalities and even their voices are as vivid in my recollection as if only a few months had intervened.

Forty-one years have come and gone, the valleys of the Columbia and the Kootenay are now studded with villages and towns. In The Crows Nest Pass 1000s of miners are at work. The Elk River Valley, which was covered with a growth of the finest trees I ever saw—fir, tamarack, and spruce—is a desert waste of stumps and blackened tree trunks. Evidence of the wilful destruction of our natural resources.

Where only a pack trail follow the winding of the valley, a fine highway for automobiles runs from Golden to the boundary, and where nothing but the bark canoe or the dugout carried the traveller by water to the outside world, the iron horse eats up the miles in a few hours which would have meant days of travel 40 years ago.

Instead of small Indian garden patches, alfalfa, grain, vegetables of all kinds of fruits, both on the trees and bush, are raised in profusion on well-equipped farms. An up-to-date golf course has been laid out on the Lower Columbia lake at Windermere. It is advance, I suppose, but I sometimes look back with something like regret over the chasm of 40 years, to the time when life was all ahead and we took no thought of the morrow.

* * * * *

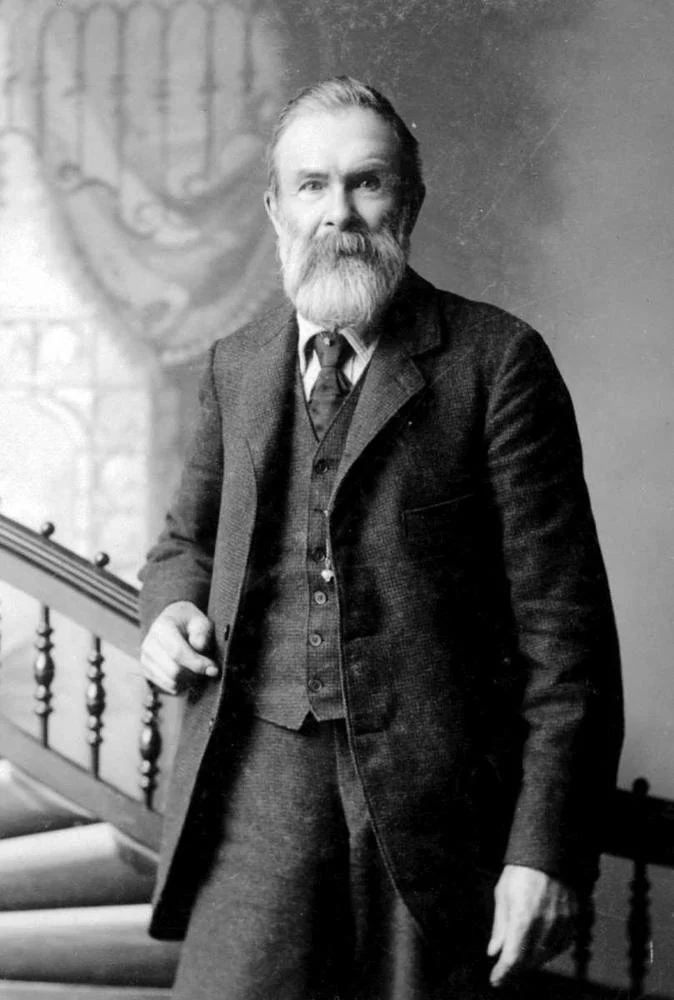

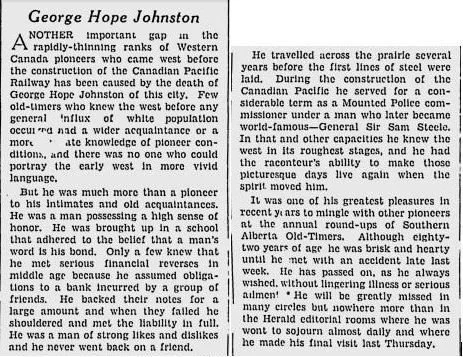

George Hope Johnston

Calgary Herald, October 1938

Another important gap in the rapidly-thinning ranks of Western Canada pioneers who came west before the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway has been caused by the death of George Johnston of this city.

Few old-timers who knew the west before any general influx of white population occurred had a wider acquaintance or a more intimate knowledge of pioneer conditions, and there was no one who could portray the early west in more vivid language.

But he was much more than a pioneer to his intimates and old acquaintances. He was a man possessing a high sense of honour. He was brought up in a school that adhered to the belief that a man's word is his bond. Only a few knew that he met serious financial reverses in middle age because he assumed obligations to a bank incurred by a group of friends. He backed their notes for a large amount and when they failed he shouldered and met the liability in full. He was a man of strong likes and dislikes and he never went back on a friend.

The Calgary Herald’s farewell tribute to pioneer George H. Johnston.

He travelled across the prairie several years before the first lines of steel were laid. During the construction of the Canadian Pacific he served for a considerable term as a Mounted Police commissioner under a man who later became world-famous—General Sir Sam Steele.

In that and other capacities he knew the west in its roughest stages, and he had the raconteur’s ability to make those picturesque days live again when the spirit moved him.

It was one of his greatest pleasures in recent years to mingle with other pioneers at the annual round-up of Southern Alberta Old-Timers. Although 82 years of age he was brisk and hearty until he met with an accident late last week. He has passed on, as he always wished, without lingering illness or serious ailment. He will be greatly missed in many circles but nowhere more than in the Herald editorial rooms where he was want to sojourn almost daily and where he made his final visit last Thursday.

* * * * *

It’s interesting to note that in his talk to the Calgary Historical Society, George Hope Johnson made no mention of the time, while serving as commissioner of police in 1885, he was charged with, and pleaded guilty to, “obstructing Special Constables John Miles and Arthur Hubbard, and with abetting the rescue of James Ruddick from lawful custody”.