B.C.’s Worst Avalanche

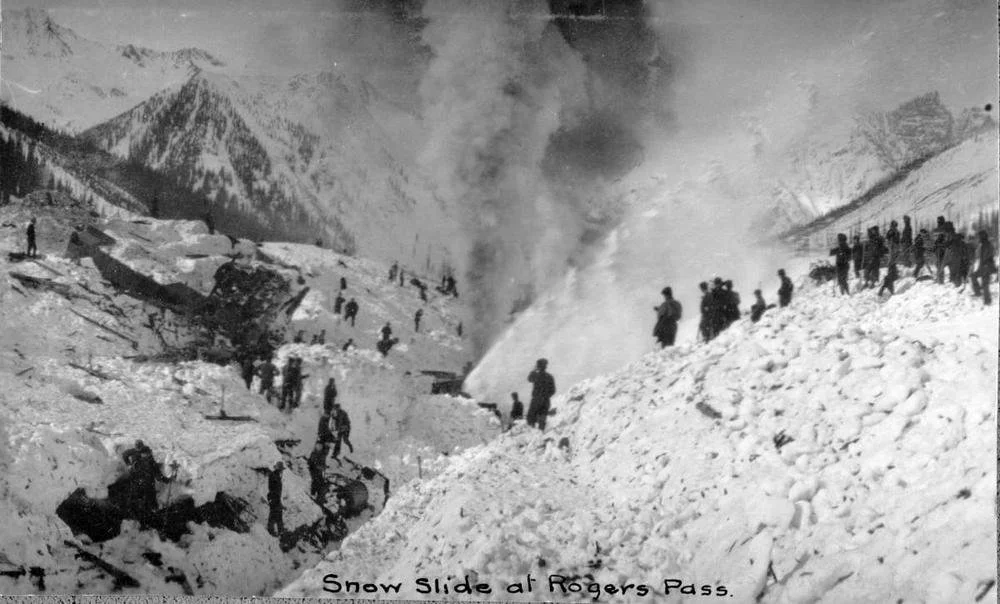

Digging out the bodies and wreckage in the aftermath of one of B.C.’s worst railway and weather disasters. —BC Archives

The date: Mar. 4, 1910.

The site: Rogers Pass.

The toll: 62 railway workers swept away or buried alive.

The legacy: the worst avalanche disaster in Canadian history.

* * * * *

Overnight, news of the catastrophe swept the Pacific Northwest and Canadian and American newspapers rushed to press with the known details beneath glaring headlines:

A TERRIBLE DISASTER NEAR ROGERS PASS – Vernon News

DEATH TOLL REACHES 92 AT ROGERS PASS - Tacoma Daily Ledger

DEATH TOLL OF AVALANCHE – Niagara Falls Daily Record

ROTARY SNOW PLOW AND GANG BURIED UNDER DEBRIS – Vancouver Daily World

SIXTY-ONE ARE REPORTED KILLED NEAR ROGERS PASS – Victoria Daily Times

SNOWSLIDE SWEEPS 50 TO DEATH – Nanaimo Daily News

HUNDREDS OF WORKMEN DIG FOR BURIED COMRADES – Vancouver Province

And so it went as B.C. newspapers scrambled to provide the latest with news of the tragedy, albeit with varying degrees of accuracy, the number of men killed ranging from 50 to 92. The Victoria Times headlined that there were 24 “white men” and 37 Japanese among the victims.

(Perhaps, before we cry racism, it should be pointed out that when listing the names of the known victims, only those of the CPR train crew and a few company “bridgemen were immediately available. The names of the workers who were employed by a contractor couldn’t possibly be sourced in the few hours before going to press.)

* * * * *

Today, Rogers Pass continues to serve as a vital route for rail and road traffic and is a National Historic Site within the heart of Glacier National Park. Although it has been argued in hindsight that Major A.B. Rogers’ namesake in the Selkirk Mountains wasn’t the best choice of transcontinental routes, once chosen, the CPR was stuck with it.

An 1886 Canadian Pacific Railway survey crew. Theirs was an incredibly challenging assignment. —BC Archives

Not that the railway hadn’t seen from the start that operational maintenance through mountainous winter weather conditions would be an ongoing challenge— contrary to Rogers’ Pollyanna belief that his route would present no special engineering difficulties. He was deadly wrong, we know now.

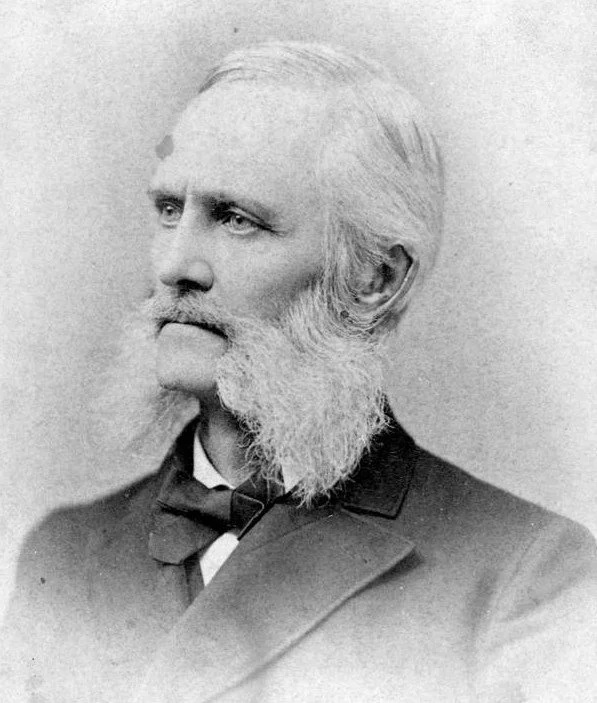

Major A.B. Rogers gets the credit for finding a railway route through the pass that bears his name but he totally underestimated the challenges of keeping it clear of snow in the winter. —BC Archives

During construction, in February 1886, not one but three avalanches thundered down on the thin steel line. The first, six miles west of the summit, killed a single worker; a second slide two miles distant, buried three men whose bodies were never recovered. The third slide had a happier ending: when snow crushed a camp store its six occupants were able to crawl out through a window.

After a change of route the battle against nature continued. Ultimately, human determination succeeded and mostly regular railway traffic began. But the war against snow had just begun.

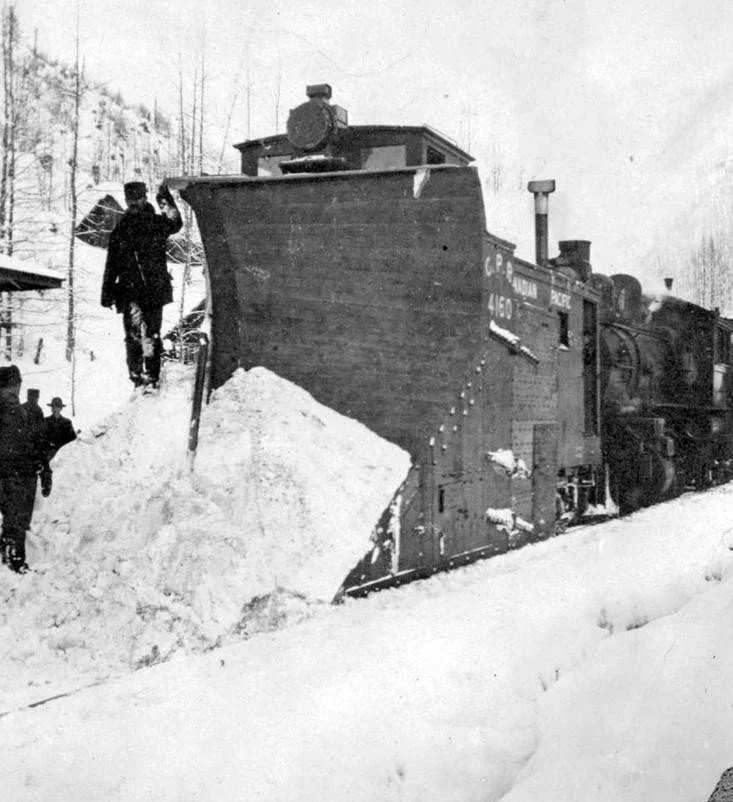

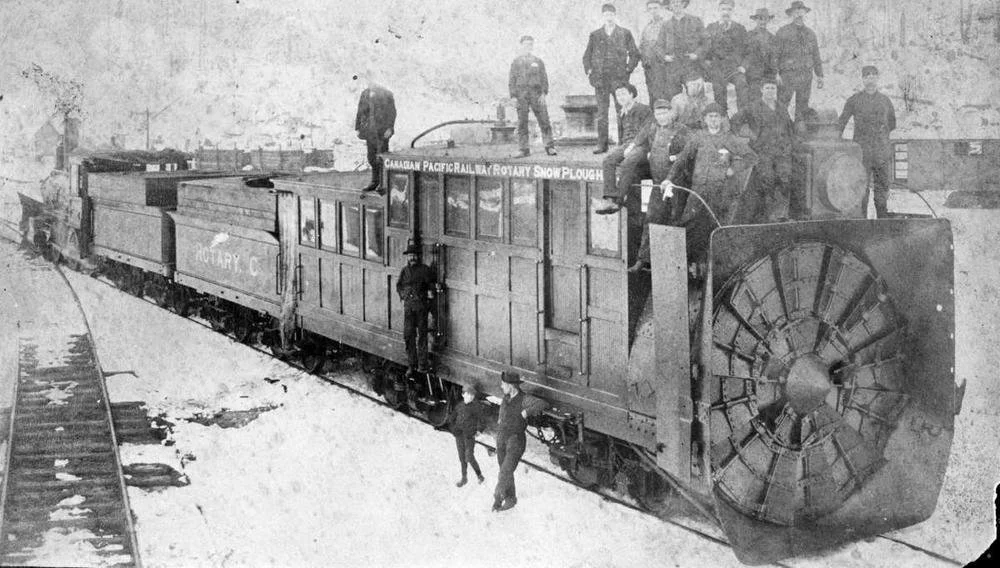

Initially, the railway had placed its faith in 31 sturdy snow sheds with a combined length of four miles that required constant patrolling—for snow damage in winter, for fires ignited by sparks from the steam engines in summer. Snow plows—massive bulldozer-style blades mounted in front of locomotives, and a rotary plow that acted like a monster leaf blower—did their best to keep the tracks open while gangs of workers tried to clear the shed entrances with little more than shovels, picks and strong backs.

A CPR snow plow mounted in front of a locomotive. —BC Archives

Usually, it worked, the line being cleared of obstructions within hours.

Almost miraculously, several stuck passenger trains escaped without mortality; in one instance, with the pass stoppered by snow at both ends, a passenger train was stranded for several weeks.

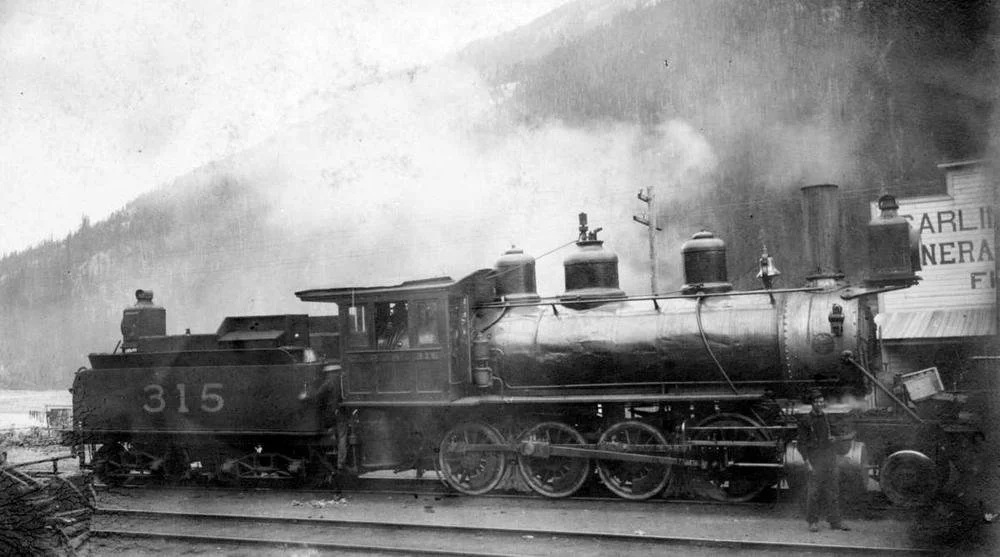

More than once, bulky locomotives weighing 100s of tons were lifted bodily from the rails and flipped onto their sides. Slowly, however, human ingenuity won out with refinements to the right of way, the snow sheds, plows and brute labour.

Behemoths such as engine No. 315 could be picked up, carried along and flipped over by the force of the avalanches that bedevilled the CPR in Rogers Pass. —BC Archives

Then came the great slide of March 4, 1910. For two months, winter conditions had created an unstable snow pack with each successive snowfall laying lightly upon its predecessor instead of bonding into a single, solid mass...

One of the first to go to press with the earliest details was the Vancouver Province:

HUNDREDS OF WORKMEN DIG FOR BURIED COMRADES

Three Score Swept to Death Early This Morning at Rogers Pass at the Summit of the Mountain

RELIEF TRAINS RUSH TO ASSIST

Workmen Were Clearing Smaller Slide When the Second One, From Opposite Side of Bear Creek, Overwhelmed Them

Under direction of roadmaster John Anderson, the workers, one of them his brother, began to clear the entrance to No. 14 snow shed. Work went well enough that he hiked to a nearby telegraph post to report progress. Doing so saved his life—that’s when the second slide, this one more massive then the first came from the opposite side of the canyon to bury a 400-long stretch of track 50 feet deep—and the train crw and section gang.

To his shock, upon rushing back from sending his telegraph, Anderson stood in total darkness with only the frail light of a lantern as the wind howled about him. There was nothing to be seen. Everything, he recalled with a shudder, was buried, the rotary plow “pitched on top of the shed”.

The rotary plow was picked up bodily and deposited on top of the snow shed. —BC Archives

By the time the Province went to press, only five bodies, said to be terribly mutilated, had been found and it was feared that not one of the workers had escaped alive. Retrieval of their bodies would, it was estimated, take three or four days.

All the while, making the recovery operation even more of a nightmare, the slides continued.

As for scheduled transcontinental rail service, life went on with trains being rerouted via the Arrow Lakes, Nelson and the Crowsnest Pass.

Response had been immediate. As soon as word reached Revelstoke the fire-bell was rung and, within half an hour, a relief train was speeding eastward with doctors, nurses and more than 200 railway workers. They were on the scene by 6 a.m. digging, it was said, “with vigour”.

From Calgary, a second train had sped westward with medics and 150 navvies and volunteers, arriving only four hours after its predecessor. On his way from Vancouver was T. Kilpatrick, acting superintendent of the CPR’s Pacific Division.

With so little hope for survivors, it seemed a foregone conclusion that the lethal avalanche was the worst of its kind in B.C., even Canadian history.: “The disaster is easily the worst experienced in the mountains since the completion of the line. It has almost become a byword that although occasional slides occurred the existence of snowsheds and a perfect system of patrolling the tracks near unprotected spots had hitherto, with rare exceptions, prevented any serious accident.

“No passenger or freight train were ever swept away and no passenger ever lost his life. Ten years ago a section house and eight or nine men were buried in a slide that tore down the mountain in the same vicinity...”

It began early that morning, in a mix of rain and sleet, when a rotary plow and crew arrived in the narrow Bear Creek valley that flanked the rails and set to work. They ignored the continuing chorus of avalanches all around them, having become, it was said, “inured to such risks”. Within half an hour, they’d removed half of the first slide.

At 12:30 a.m., there was a second slide, this one coming from the opposite side of the valley. The Province described what followed in breathless prose: “Thousands of feet above a few rolling bunches of snow grew in volume and momentum started on its pathway of destruction. In a few seconds, with a noise like a thousand thunderbolts crashing in unison, it leaped from shelf to shelf, uprooting and carrying with it a tangled mass of trees, ice and large boulders.

“There was no escape for the unfortunate railwaymen.

“It piled on top of the first side, burying the tracks for a distance of a quarter of a mile and to a depth of 50 feet. Hundreds of thousands of tons of other debris in the wake of the avalanche bounded off the huge heap and half filled the valley of Bear Creek hundreds of feet below.”

If there was any good news it was that the eastbound No. 96 Express had just reached Glacier when word of the slide shut down the line other than for relief trains.

By this time an estimated 600 men were shovelling and clawing at the debris in search, not for survivors, but for bodies, while also trying to clear the line for traffic. To this point only five bodies, those of Roadmaster Fraser, Fireman Griffith, Conductor R.J. Buckley, engineer W. Phillips, and one Japanese navvy, name unknown, had been recovered in blizzard conditions that further delayed recovery and repair efforts.

For days, the grim task of digging out bodies went on as the mountains continued to thunder with more snow slides. —BC Archives

On the third day, it was reported that 14 survivors and 30 bodies had been found—many of the latter still clutching their picks and shovels, some of them still standing upright. It was surmised that, deafened by the roar of the rotary plow, they hadn’t heard or seen the avalanche roaring down upon them.

The number of victims had been confirmed as 62, which included the train crew, bridge workers and the section gang. Those bodies yet to be found were thought to have been swept into Bear Creek, 100s of feet below.

And they didn’t dare put the rotary plow to work for fear of mutilating bodies.

The heroic recovery operation had been conducted under horrendous conditions: “The wind blows through the pass with terrible force and the rescuers are greatly hampered in their work.” This was followed by a chinook wind and warm rain that hastened the thaw and threatened further slides.

The Vernon News noted that the “portion of the line immediately east of Rogers Pass is admitted by all railroad men to be about the most dangerous piece of work in the whole mountain division... The line at this point is at an altitude of about 5000 feet, and the mountains tower above the track for several thousand more feet, thus giving tremendous velocity to a mass of moving snow when disturbed and started on its downward course.

“There are nearly seven miles of snowsheds between Glacier and Beavermouth, and where there are gaps between the sheds, special chutes have been built high on the mountain side which divert slides, in almost every instance, from where the track is unprotected, so that they sweep harmlessly over the sheds into the valley thousands of feet below.”

Alas, “where the avalanche occurred last night there were no snow sheds to protect the track, but if it had come down a few hundred yards further east it would have been diverted by the chute onto the sheds.”

[This, we know, is incorrect; they were digging out a snow shed when caught by the slide.—Ed.]

Another of the few survivors was 27-year-old locomotive fireman Bill LaChance who’d experienced other slides hitting his locomotive but nothing like this one. It struck with such force that it flipped the engine upside down in the snow. Incredibly, he was thrown free of the cab and propelled in a ball into the maelstrom; when he came to rest he had a broken leg and was buried several feet down.

He was able to scrape enough snow from around his face to breathe until miraculous rescue. By then he was hypothermic and in shock; enough so that doctors originally despaired of his recovery. To everyone’s surprise he was back on the job just weeks later.

Railway worker Duncan McRae also lived to tell the tale—not only alive but uninjured—after the force of the slide left him stop the snow shed he’d been helping to clear. He said it felt like he was walking on water as he was swept along on a tidal wave of snow, rocks and other debris.

As for survivor John Anderson, it’s said that he never recovered from the loss of his brother and his crew, never speaking about the event even to family members.

A further tragedy of the 1910 Rogers Pass avalanche is that there is so little available to us today in the way of personal accounts, not even in the Revelstoke Museum. We can only imagine the horror, hardship and heroism of the 100s of rescuers, some of them only teenagers, who volunteered and, handed shovels and picks to attack snow which had turned to ice, joined in the search for bodies.

Another tragedy is that little is known of the Japanese victims, only one of whom survived because he’d downed tools and moved off to the side to eat.

Fourteen of the victims lie in the Revelstoke cemetery, some with markers, some without.

* * * * *

Mainline service was soon restored but CPR brass knew drastic changes had to be made. They decided to bypass the most dangerous stretch of track by boring the eight-kilometre-long Connaught Tunnel. It took three years.

Cars now safely navigate Rogers Pass, protected from snow slides by this tunnel. —BC Archives

As snow slides continued to threaten both ends of the tunnel, more snow sheds were built and service achieved both safety and regularity.

And parts of the abandoned grade became a national park and tourist attraction.

* * * * *

In 1962, Rogers Pass was opened to automobile traffic upon completion of this mountainous stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway, the CPR engineering studies of old having proved invaluable to the highway engineers. Today, the battle against snow continues but with the added armament of more than a century of scientific meteorological study—and artillery, used to circumvent slides before they happen.

CPR engineers and builders couldn’t have imagined today’s highway travel through Rogers and other B.C. mountain passes. —BC Government

On the 105th anniversary of the killer avalanche, Jeff Goodrich, senior avalanche officer for Parks Canada told the CBC, “The scale of the tragedy that happened that day 105 years ago just gives you pause to think... It reminds you that you do have to treat an area like this with respect and to always be vigilant.”

* * * * *

How ironic that B.C.’s worst avalanche disaster followed that of next door Washington’s by just three days. There, at 4 o’clock in the morning of March 1st, the westbound Great Northern Railroad’s Spokane Express and a mail train were struck by a slide during a thunder and lightning storm. Both trains were shoved down a 150- foot-deep gorge and buried in up to 70 feet of snow.

There were 23 survivors but 96 died, their bodies having to be retrieved on toboggans as there was no other available transport.

Even as railway workers and volunteers searched for bodies in Rogers Pass, shown here, the same horrific scenes were being enacted in Washington on the Great Northern Railroad. —Wikipedia