Big Jim McLaughlin, Terror of the Tenderloins

Prospector, packer and painted lady; merchant, gambler and thief; they all called rip-roaring Fort Yale home at the height of the Fraser River and Cariboo gold rushes.

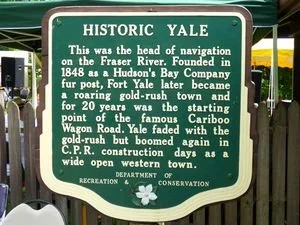

For years, Fort Yale, originally a Hudson’s Bay trading post, was British Columbia’s own Dodge City.

Here, on the Fraser’s western flat, bonded in restless union by their quest for gold, 9000 men, women and children from every quarter of the globe toiled, fought and died for the elusive metal.

Of this motley populace, one man towered above his fellows.

The proudest grew humble before his command, brave men faltered, women fainted, dogs and children flew terror-stricken from his rage. Undisputed monarch of all he surveyed through eyes bloodshed red, he was Big Jim McLaughlin, the terror of the tenderloins.

* * * * *

“He was a most desperate blackguard, both in appearance and action,” recalled pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins, whom we’ve met before in the Chronicles (The Case of the Wrong Saddlebags), 50 years later. “He was a huge, bloated specimen of humanity and was generally filled to the throat with drink.”

He was, in fact, the town butcher.

In the whole of teeming Fort Yale, there was but one meat market. A state of affairs which tickled the perverted fancy of jaundiced Jim no end, for every man, woman and child in the community, regardless of fortune or fame, relied upon him for a steady source of fresh meat. Until some one dared set up shop in competition, McLaughlin reigned supreme.

From his throne, a carving block, McLaughlin regarded each and every customer with open contempt. Every order was served with insults and curses. When suffering from a hangover, as often was the case, he even threatened assault, his ravaged face glowing redder as his temper flared ever higher.

For those foolhardy enough to express indignation, Jim had two favourite tricks. Firstly, he’d fill the order with obviously inferior cuts and wait belligerently, yellow fans bared in a sadistic smile, for complaint. It seldom came.

Then, adding insult to injury, he’d openly lean a ham-like fist on the scales when weighing the purchase.

“He insulted and bullied everyone...” wrote Higgins in 1904. “He could cut off the supply of meat at any moment... The language he used was fearful to listen to. He browbeat women as well as men.

“He hated children and often would turn them away without the food they had been by their parents to buy.”

Foraging dogs, sighed Higgins, afforded McLaughlin “his greatest joy and satisfaction”. Every canine was greeted with a heavy foot, a string of curses, and “once or twice with deadly effect,” a flying meat cleaver.

“How we submitted patiently to the tyrannous conduct of the ruffian, even at the risk of losing our meat supply, I cannot imagine now. He led us captives to the block and decapitated us morally, if not physically...

In 1904 onetime Yale express agent D.W. Higgins told the story of Big Jim McLalaughlin in a series of reminiscences in the Colonist and later in two books.

I had two or three tilts with the fellow and every time was worsted because he held the key to my stomach.”

Jim’s crimes were legion. Like the hapless morning a Scottish prospector’s terrier wandered into the shop to beg for scraps. With a roar of outrage, Jim had seized his knife and slashed at the dog’s back. The maimed terrier then dragged itself out, bleeding profusely, from the shop and collapsed in the street.

Immediately informed of what had happened to his little companion, McDermott had grabbed a revolver and charged to the meat market, friends at his heels vainly imploring him to surrender the gun. The enraged miner ignored their pleas and marched into the shop, pistol in hand.

Fortunately for McLaughlin, McDermott had by then calmed somewhat. Aiming the muzzle of his pistol at the butcher’s pudgy face, he swore: “If I ever catch you on the other side of the line I’ll kill you—kill you.”

Instantly, Jim’s confidence returned.

Realizing that the Scotsman wouldn’t fire, he laughed, “Go on out of this, or I’ll serve you as I did the dog!”

Frustrated by his own impotence and McLaughlin’s sneer, McDermott had stomped out with the promise, “Remember, you will be my meat if I ever catch you on the American side.”

The butcher had spat, motioned suggestively, and the incident was closed.

But Big Jim’s time was running out, his Waterloo fast approaching. As has happened so often in history, the worm was to turn. And, as has so often been the case in times old and new, the mighty was to fall before the feet of a tiny woman.

Which makes this a good time to introduce the other members of our cast.

* * * * *

Fraser River at Yale where Mrs. Burroughs lived in a tent with her children while waiting for her husband. —Wikipedia

Journalist Higgins was 24 when he joined the rush for gold on the Fraser River. Previously, he’d spent six years recording the hectic affairs of rough-and-tumble San Francisco. Forty-niners, the famous Vigilance Committee: he knew them all. In July 1858 he’d traded his pen for pick and pan in a short-lived, unsuccessful attempt at mining in Fort Yale where he then found a job as an express agent. It was here that he encountered the loathsome Jim McLaughlin.

At least two others of his acquaintance shared this dubious distinction. The first was an Irishman, Capt. William Power, later to make his fortune in the Vancouver real estate boom. “A “splendid specimen of manhood and...an accomplished athlete,” Capt. Power had met the stocky journalist aboard the steamer bringing them upriver, when looking for a steward.

The refined captain had been in search of water for shaving. “I’ve travelled all over Europe and the Holy Land and have been on the Nile, but this is the first time I have found it impossible to get a cup of hot water to shave with,” he’d said with a sigh.

Soon, Powers introduced Higgins to his lovely wife; by the time they reached Yale the three were fast friends. Landing at the booming gold town, they’d pitched tents on the river flats. Higgins secured employment as manager of an express office while the Powers opened a hotel which was immediately successful.

It was through Powers’ buying foodstuff for his for his establishment that he frequently endured the abuse of the vitriolic McLaughlin.

Much to Powers’ disgust, “his restraint was at the mercy of the bloated butcher. He [Jim] could cut one off the supply of meat at any moment and put Power out of business.”

The third character of our melodrama is a frail English lady, Mrs. Burroughs. With her young son and daughter, she lived in a small tent on the river bar. Some time before, her husband had ventured upriver in search of his fortune, leaving them a meagre supply of groceries and money.

Soon all had been exhausted and Mrs. Powers was reduced to “great straits”. Her neighbours, most of them in grim circumstances themselves, did what they could to help. Despite her situation, the heroic mother refused to seek aid. But winter was approaching and her family’s future fast becoming desperate.

Remarkably, McLaughlin had allowed her several purchases on credit. But, one fateful autumn morning, the inevitable encounter came to pass.

Mrs. Burroughs had taken her place in the line awaiting Jim’s pleasure. Service was slow as the evil monarch was recovering from a double hangover—too much rotgut whisky and a bad night at the faro table.

When, finally, it was Mrs. Burroughs’ turn before the carving block, the wretched McLaughlin had stared through bloodshot eyes then bellowed, “What do you want!?”

Timidly, the woman had answered, “I should like to get a little more meat on credit for a few days. Mr. Burroughs will be here soon and he will pay you.”

Leering diabolically, Jim leaned on his knife and smirked, “Is there a Mr. Burroughs? Was there ever a Mr. Burroughs? I doubt it!”

Recounted Higgins: “The hot blood mounted to the woman’s face and painted it crimson.

“She fixed her eyes in a terrified stare on McLaughlin and her lips moved as if to remonstrate; but no words came from them. She leant forward on the block and then sank to the floor. She had fainted dead away. Strong hands raised the thin, wasted figure (for it turned out afterwards that for some weeks she had systematically lived on the shortest of short allowance so that her children might have enough to sustain them), and a low murmur of indignation ran through McLaughlin’s subjects who awaited their turn to be served.”

Unmoved by his victim’s collapse, the monster then turned to the next customer and barked,”Come on now, and give your orders quick. I can’t stand here all day. What do you want?”

The customer, “white as a corpse,” didn’t answer immediately. Capt. Power stood in stunned disbelief of the tragedy he’d just witnessed. When at last he spoke, his words came in a slow, measured tone: “McLaughlin, every time I come in your shop I am insulted. This thing has got to stop.’

Pointing to Mrs. Burroughs who was being led gently away in the arms of two miners, he continued: “I don’t care so much for myself and I could have stood it, but I do care for that poor little woman.”

The captain’s rebuke ignited Jim’s demonic fury. Roaring like a wounded beast, he threw down the carving knife, ripped off his bloodied apron and charged Power. But the latter stepped neatly aside and delivered a smashing blow to the puffed face as it reeled past.

The “fight” ended in moments, Power “raining blow after blow with smashing effect upon his antagonist’s face and body until the latter sank, insensible, to the floor and stayed there, the bad blood and the bad whisky flowing from numerous wounds.”

Without so much as a downward glance at the fallen monarch, Capt. Power sauntered behind the infamous block, selected a cut of meat, weighed it, threw down 40 cents, and walked leisurely towards his hotel, as a spectator called after him, “I think the man’s dead, Power.”

“Well, if he is dead, you know where to find me,” replied the captain without turning.

However, much to Yale’s regret, Jim lived. For hours he lay in the dirt where Power had left him, not a soul moving to help him. When at last he regained consciousness, the battered butcher had pulled himself painfully erect. Then, although “groggy on his pins,” as he expressed it, he resumed his duties, viewing his customers hazily through eyes swollen and almost closed.

But the Jim McLaughlin who now waited on a quavering clientele was a changed man. Not an insult escaped his crushed lips; where, before, his fist had accounted for half the weight registered on his scale, he now carved generous cuts with scarcely a glance at the weight.

“Every trace of ruffianism had oozed out through his wounds and in place of the bully whom everyone feared and hated there stood a polite and decent whose manners were almost obsequious and who never again was known to browbeat or insult a customer.”

Once, women, children and dogs had been the favourite targets of his invective—and worse.

Now, he couldn’t do enough for one and all. Sending for McDermott, the Scottish miner, he pleaded with him to send his dog to the shop, that he might feed him daily. As word of his magnificent reformation spread, the beaming butcher butcher’s popularity soared. Those who’d fearfully addressed him as Mr. McLaughlin soon began calling him Jim and Mac.

Almost as extraordinary as McLaughlin’s change of disposition was his change of evil pursuits. Swearing, gambling and drinking were now sins of the past. “Boys,” said he to his former drinking partners, “I’ve drunk my last drink and I’m going to save my money from this time on forevermore till Kingdom Come—so don’t tempt me, for I won’t go.”

When a Methodist missionary paddled into town a year later, it was Big Jim McLaughlin who greeted him with open hand and heart, and who attended the first sermon. He even joined in singing the hymns. “You know,” he said with a blush as he awkwardly crushed his hat in his calloused hands, “I used to belong to a choir when I was a young fellow back in Maine.”

“But the strangest part of the affair,” marvelled journalist Higgins in 1904, was that Jim never by any chance referred to the “pounding that he received at the hands of Power. Asked as to how he received the injuries on the face he would attribute them to running against a side of beef in the dark. His memory of that event seemed a blank.

“All that he knew was that he had been hurt, he believed, by accident, and that was all there was to be said.”

For Mrs. Burroughs, her sad story wasn’t ended. Months after, a miner rushed into town with word that a companion had shot himself in the leg, down the trail, while climbing over a fallen tree. By the time a doctor reached the scene, the man had bled to death. A search of his clothes revealed $700 in gold dust and letters bearing the Yale postmark, addressed to Charles Burroughs, Lytton.

Inquiry failed to locate a single person who’d known the deceased until Jim McLaughlin suggested asking Mrs. Burroughs. Sadly, as some had come to fear, Charles Burroughs had been her husband. He’d been returning with his purse of hard-won gold when the accident occurred. One of his acquaintances on the trail later told Higgins that Burroughs had been in high spirits and singing, The Girl I left Behind Me when disaster struck.

When Burroughs was interred in Yale’s small cemetery, Higgins and McLaughlin led the pallbearers. After the ceremony, it had been Jim who humbly stepped forward and took a child in each arm as Power gently offered his arm to the grieving widow.

A week later, Mrs. Burroughs left Yale for friends in California and never returned.

In 1860 D.W. Higgins moved to Victoria which was to be his home for the remainder of his life. Over the years, he lost touch with his former friends in Yale. Among this vanished company was Jim McLaughlin. Fifty years after, Higgins had wondered: “Was the regeneration of Jim McLaughlin permanent? I do not know. I hope that it was for at the bottom he was a good sort and was capable of noble actions.

“Let us trust that he never lapsed into evil courses, and that as he must have long since gone the way of all flesh he continued to grow in grace until when the end came he won a starry crown.”

Unknown to the retired journalist, in 1872, the Colonist had published a brief summary of of the activities of the province’s more successful citizens who’d gone on to bigger and better things.

Among the list was the name James McLaughlin, formerly of Yale. He was in San Francisco, and doing well.

—Wikipedia

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.