Byron A. Riblet, Tramline Titan

I recently reported that a new book has been released across the line in Washington.

Byron Riblet: Forgotten Engineering Genius by Ty A. Brown is the second book written in recent years of the man who, with his brothers, perfected the tramlines that are in use around North America and mostly identifiable, today, as ski-lifts.

But these ungainly sinews of towers and cables that can span almost any kind of terrain, started out as tramlines to carry ores from isolated and mountainous mining operations. The Riblets brought one of their effective and economical cable systems to the Cowichan Valley just after the turn of the last century.

That’s when they were commissioned to connect the Tyee Mine on Mount Sicker to the E&N Railway at Tyee Crossing, three miles distant by cable, the copper ores being carried in aerial buckets.

Looking up from above the Lenora town site on Mount Sicker to the ore pile of the competing Tyee Mine which Byron Riblet and his brothers successfully linked to the E&N Railway with their aerial tramline.

It was far more efficient and less costly to build and to maintain than the competing Lenora Mine’s narrow gauge railway to Crofton. With the Tyee’s closure, the tramline hardware was recycled at a mine in the Barkley Sound area.

Sadly, until recent years, two of the wooden towers had survived, tall and firm, but were downed by loggers.

Sadly, too, although there’s an entire chapter on the Riblet tramlines in B.C.’s silvery Slocan, not a mention of the Tyee on Mount Sicker. A slight that I correct in this week’s Chronicle.

* * * * *

My ready reference on the local side of things is my own 2007 history of the Mount Sicker mining frenzy in the early 1900s, Riches to Ruin: The Boom to Bust Saga of Vancouver Island’s Greatest Copper Mine.

Which should have been, in truth, copper mines, as there were two phenomenally rich producers on Mount Sicker, the competing Lenora and Tyee Mines. It’s the Tyee that’s the subject of today’s tale.

As we’ve seen in a previous Chronicle, Hiking Henry Croft’s Dream Railway Henry Croft, manager of the Lenora operation, went to great expense—so great that it hastened the demise of the Lenora Mine and ruined him, to build a narrow gauge railway. It had to wind around and down Mount Sicker, cross the Westholme Valley (just south of Russell Farm on the Trans Canada Highway), and skirt Mount Richards to his deep sea port at Crofton.

Henry Croft’s railway cost him dearly, a mistake the Tyee Mine management were determined not to repeat. —Author’s Collection

So, before introducing Byron Christian Riblet & Co., the story of the Tyee tramway.

* * * * *

“Messrs. Ribelt and Painter, both of Nelson, B.C., have been in Duncans in connection with the aerial tramway which it is proposed to build from the Tyee mine to a point near Somenos on the E.N. [sic] railway.”

Such was the Crofton Gazette’s first mention, March 27, 1902, of the Tyee Copper Company’s answer to getting their ores down the mountain. No ambitious and expensive railway for them. Let Henry Croft risk his shirt on building a railway down and around, over, under, through and across steep grades, hazardous switchbacks and often raging creeks!

Theirs was a much simpler solution, particularly as they had no intention of sending their ore to be smelted at Crofton. All they had to do was to get it to the E&N, 1700 feet, elevation-wise, down the mountain from whence it was off to Ladysmith and their own smelter. A straight line (more or less) three and one-half miles long, over the spine of Big Sicker Mountain and down to Stratford’s Crossing, Somenos, would do just fine.

As ever, there’s much more to the story than this.

In his memoirs, Air Marshal Sir Philip Livingston, KBE, CD, AFC, FRCS, son of Tyee Mine General Manager Clermont Livingston, recalled that, in the beginning, the Tyee had an agreement “on equitable terms” to ship its ore on Henry Croft’s new railway.

However, this arrangement didn’t last long as the well-established territorial imperative between the two umbilically linked neighbours reasserted itself. The Tyee, according to the younger Livingston, found itself in “the grip of its rival” and feared that the Lenora management would exercise its new-found tactical supremacy...to crush the Tyee, and mould the residue into the ‘Le Nora’ [sic] organization”.

Half a century after, Sir Philip recalled how his father had paced ‘Clevelands,’ the family manse at Cowichan Bay, night after night, too worried to sleep, until “he was nearly to the breaking point”. It was then that the Tyee Copper Co. resolved to haul its ore down the mountain by means of an aerial tramway.

At the April meeting of North Cowichan Council, Livingston requested and was granted permission for a right-of-way over which to build a Riblet tramway between the mine and the railway.

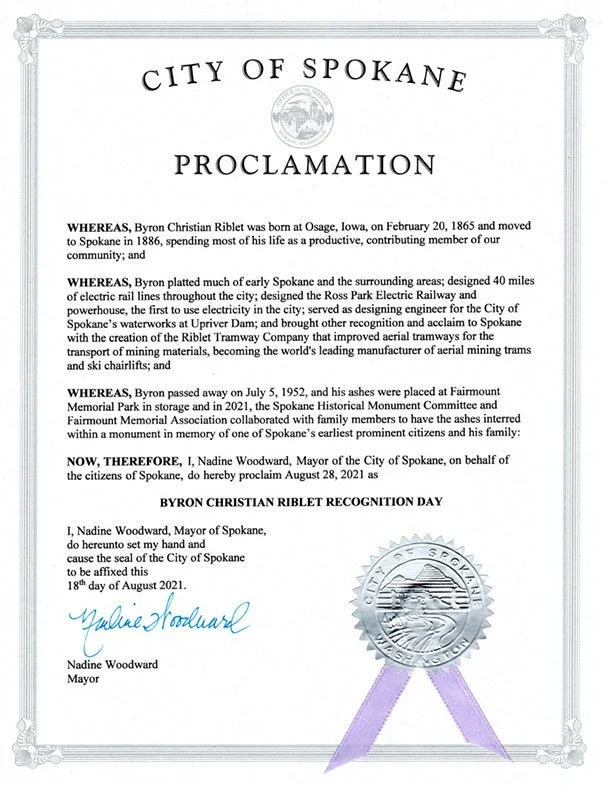

The inventive genius behind this extraordinary network of wooden towers and steel buckets was 37-year-old Byron Christian (‘BC’) Riblet (1865-1952). A civil engineer form Iowa, he first worked for the Northern Pacific Railroad then on Spokane’s ‘tram’ (streetcar) system before he and brother Walter began manufacturing aerial tramways in Nelson in 1896.

Their Riblet Tramway Co. would ultimately erect systems in the Kootenays, the Boundary region, on the coast, in the Klondike and the Rocky Mountains. “If there was a tramway to be built in the Canadian West or beyond...Riblet stood ready to build it.”

Although all three Riblet brothers, BC, Walter and Royal, made their careers in designing and building these overhead haulage systems, mostly for mining companies in the beginning, Martin J. Wells chose BC Riblet for his 2005 book,Tramway Titan, crediting him as the inventor of the “first reliable mining cableways in British Columbia and the northwestern United States”.

The Riblet Company went on from mine tramways to modern ski-lifts. —Wikipedia

More than a century after, the Riblet Tramway Co. remained in business in Spokane, WA, primarily as builders of “quality and effective Double, Triple, and Quad fixed-grip chairlifts” for ski resorts. The company finally went out of business in 2003, its venerable tramway/ski lift designs having been surpassed by space-age competitors.

‘Last man standing’: the concrete foundation of the Riblet tramway beside the ore dump of the Tyee Mine. —Author Photo

From the pages of Crofton’s Gazette (another child and casualty of the short-lived Mount Sicker copper mining boom) we get this running description of the tramway’s construction from late spring through the summer of 1902:

May 15 – A strange accident happened to a Chinaman [sic] who was working on the right-of-way for the Tyee aerial tramway. Two Chinamen were undercutting a log, and one slipping, fell upon the saw. The other at the same moment drew the saw and literally cut his fellow-worker’s throat. The injured man by latest reports is just alive. [There was no follow-up to this so we may assume that the unfortunate worker survived. —Ed.]

August 6 – The ore bins being built for the Tyee Copper Company at Stratton’s [sic] Crossing, near Somenos, on the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway, are nearly completed. Messrs. Keast & Lewis have fulfilled their contract to haul the wire for the aerial tramway up the mountain.

August 27 – The [photo] shown below (from an interesting series in last Saturday’s ‘Times’) illustrates the Tyee Copper Company’s ore bins, whilst under construction at the terminal on the aerial tramway. The E.&N. Railway siding, at which these have been constructed, is about 1 1/2 miles north of Somenos station, at the foot of Mount Sicker.

The distance is about 3 1/2 miles and the 7/8th-inch (’on the light side’) and 1 inch (actually 1 3/4-inch ‘on the heavy side’) wire used for the line will be stretched between some 40 [sic] towers. It is one of the long double wire aerial tramways that the B.C. Riblet Co., of Nelson, have ever constructed and they have had an experience of the work which has made their name famous on the continent.

The ore buckets will carry half a ton each, and it is calculated that they will be able to convey if necessary more than 300 tons of ore a day from the mine to the railway siding. The bins themselves will have a capacity of nearly 600 tons.

The system will work automatically. Each car as it reaches the bins will by a mechanical process dump its load, and re-latching by an ingenious device will be carried along the wire way back to the mine for a fresh load. Mr. R.N. Riblet has been personally suervising the work of construction.

September 3 – The first bucket of rock sent down the Tyee aerial tram was dumped into the bins at Stratford’s Crossing at 3:15 p.m. on Saturday, the 31st August. The line will be in regular working order in a few days.

September 3 – Mr. Wm. Dwyer, of the Tyee and of Duncans, has been appointed superintendent of the lower section of the aerial tramway. Mr. Ridsdale, of the same company, will have charge of the upper portion.

September 24 – The first car loads of ore from the Tyee mine were shipped from the bins at the end of the aerial tramway at Stratford’s Crossing, on the 23rd inst. They were delivered at the Ladysmith smelter bins the same day. The aerial tramways has been running satisfactorily though not as yet frequently.

October 8 – The aerial tramway is working regularly under the guidance of Messrs. Dwyer and Ridsdale, and shipments are being made to Ladysmith. Mr. H.R. Greaves, of Somenos, having been appointed the E. & N. Ry. Co.’s agent at the bunkers. In the construction of the aerial tramway some 14 miles of wire rope are supported on 48 towers.

There are 50 buckets suspended on the line, each carrying about 1,100 pounds of ore. They make the round trip in 2 1/2 hours, and even early trials show a capacity of dealing with 45 tons in 4 1/2 hours, or say, 150 tons a day.

* * * * *

The tramway appears to have operated smoothly from Day One. In its first year of operation it transported 42,000 tons of ore down the mountain to Tyee Siding.

William Mordaunt Dwyer, the Wm. Dyer mentioned above, worked for the Tyee Mine “from start to finish,” having arrived in the future Duncan with his parents in 1884. “There seemed to be more butter, field eggs and grain then than now,” he told a Cowichan Leader reporter years later.

Upon leaving school he worked with survey parties throughout much of the province. I t was a way of life that appealed to many young men of the day, he recalled. Upon returning to the island, he helped to survey timber limits on the wet coast, in the Sayward Valley and Chemainus region before being hired as the Tyee’s hoisting engineer.

In Dwyer’s 1948 obituary the Leader noted that “he ran the first steam engine on the mountain, represented the company in the construction of its aerial tramway and what is now Stratford’s Crossing Railway siding, and when it was finished undertook the management of it and handled it for five years—’a story in itself’—Mr. Dwyer was accustomed to saying.’

During the Second World War, Dwyer returned “to the mountain” when the federal government reactivated the old Lenora and Tyee mines for their lead and zinc ores.

At least two of the sturdy wooden towers survived up until logging operations finally brought them down in 2004. Some lengths of cable still snake through the salal, now a maze of slash and new growth. Only the base of the ‘first and last’ tower survives today, at the Tyee mine site—because it’s of concrete.

If you stand at the Tyee ore dump and look upward and eastward towards the Richard III Mine, you can see the notch they cut out for the tramway in the ridge that forms the peak of Big Sicker Mountain, at the 2200-foot elevation.

During the First World War a manganese mine was operated on Hill 60, just south of Lake Cowichan. It shipped its ore down the hillside to the E&N’s Lake Cowichan Subdivision by means of an aerial tramway. Tramway Titan author Wells wonders if it was built with parts recycled from the by-then discontinued Tyee tramway.

Mount Sicker’s Riblet cable system actually went to the Ptarmigan Mine in the Alberni Canal area.

* * * * *

E&N Railway literature still refer to it as Strratford’s Crossing but, for years, it was known as Tyee Siding for the fact that it was the Tyee mine’s tramway terminal and, as of mid-1900, the site of a large sawmill.

Upon acquiring the Tyee Mine’s timber limits, some 200 acres, the Vancouver island M.&D. Company’s E.J. Hearn promised that their mill would be equipped “entirely with British Columbia manufactured machinery with a guarantee starting capacity of [20,000] feet a day”.

By this time, of course, the tramway was no longer running.

Modern houses now adjoin tramway operator William Dwyer’s house that was provided him by his employers. But there’s no sign now of either the tramline or the sawmill.

* * * * *

Which brings us to the latest book written about Byron C. Riblet by Spokane school teacher Ty Brown.

Author Ty Brown poses for the Spokane Review.

Chronicles readers who may wish to order the book can find easily contact information by Googling B.C. Riblet or any variation of Riblet Brothers.

The attached news clippings relating to Riblet tramway projects in British Columbia are courtesy of historian Jim McLefresh who undertook to save the Riblet Company’s files, plans, templates, dies and other priceless memorabilia from likely destruction.

How ironic that, years later Britannia Mines commissioned the Riblet brothers to build another tramway to haul copper ore to—of all places—Henry Croft’s long-silent smelter at Crofton!

Byron C. Riblet

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.