Capt. Bully Hayes, ‘Last of the Buccaneers’

There was a time in the age of wooden ships and iron men when a ship’s captain was God, answerable only to his conscience—if he had one.

Sure, international maritime law banned the physical and mental abuse of seamen—but just try proving that in court, after the fact, with terrorized witnesses and, often, in a foreign jurisdiction.

The only known photograph of Capt. W.H. ‘Bully’ Hayes, 1827 (or 1829)-1877. —Wikipedia

Sad to say, some ship masters got away with brutalizing their crews (and sometimes their passengers) again and again, even to the point of murder. One of the worst, at least reputation-wise, was Capt. William Henry ‘Bully’ Hayes who lived up to his nickname all too often and all too well.

He could be charming enough when it suited him—as it often did when he was trying to outwit his creditors and the law. But once on the high seas, with no one of higher authority to question his orders...

* * * * *

It’s not a term that you hear any more. But there was a time when ‘Hellship’ had real meaning. (See They Called Them Hellships For Good Reason.)

Ships from around the world called at Chemainus to load prime B.C. lumber; among them the likes of Capt. Pedersen. —Author’s Collection

I’ve written before of the legendary ‘Hell Fire’ Pedersen who’d bring his sailing ship the Puako into Chemainus from time to time to load lumber. With his two teenage sons as mates, all of them armed with belaying pins, brass knuckles and boots, he ran a tight ship—so tight that he ultimately ended up in a courtroom charged with murdering two of his crewmen. Only to be acquitted, of course; that’s pretty much the way it was in the so-called good old days.

So it was, too, for the infamous Capt. Bully Hayes, another B.C. visitor who, happy to say, did meet his just desserts; not in a courtroom but at the hands of one of his own crewmen.

In introducing you to Cobble Hill historian Nathan Dougan several weeks ago I mentioned Capt. Bully Hayes when quoting son Robert Dougan’s book, A Story To Be Told. The pioneering Dougans, who’d arrived in British Columbia by sailing with Hayes from Australia, had been blessed to see the better side of his apparent Jekyll-Hyde personality.

Which was just as well for he could be all charm itself when circumstances demanded, but hell-on-wheels when commanding his ship on the high seas and out of sight of the land and the law.

If Hayes had a virtue, it was courageousness, it being said that he “never knew fear”.

Probably just as well as he seems to have gotten himself into some serious scrapes (mostly of his own doing) during his career, including the final escapade that cost him his life.

An American, he was born in 1827 in Cuyahoga County, Cleveland Heights, Ohio, the son of a tavern owner. Unfortunately, there’s not much known about his childhood and growing-up years other than that he was educated in Norfolk, Va., and that he served an apprenticeship “with honour and promotions” in the U.S. Revenue Service.

For reasons unknown he resigned from government service and when next heard of he was commanding a steamship on the Great Lakes. Only to join the U.S. Navy and to serve, so t’is said, with distinction under the legendary Admiral Farragut. Another source is probably more accurate when it states that he was dismissed from the service while serving in China.

This wouldn’t have been the only road bump along the way.

In September 1859, the Honolulu Advertiser posted a story that dated back seven years, about the young officer and gentleman having been been accused of horse rustling! The Advertiser didn’t mix words in describing Hayes beneath the headline, “Consummate Scoundrel.” It seems that he’d appropriated a few horses belonging to a neighbour and sold them.

However, because of a faulty indictment, instead of going to jail, he’d evaded justice and fled the Islands.

Had the Advertiser mistaken him for several other mariners named Hayes who were active in the Pacific in those years, as is speculated on the website, Images of Old Hawaii? Even the British Admiralty, it seems, knew him as Capt. H.W. Hayston. An alias? If so, it fits the good guy-bad guy personality.

Whichever surname he travelled by, he continued to be widely known by his nickname, Bully.

As noted, he knew when to apply the charm, such as the time, early in his merchant marine career, that he talked a passenger into setting up his mistress (Hayes said she was his wife) in the liquor business (or as the operator of a brothel, according to another source). She wasn’t his only female consort, Hayes, although known to be twice married and the father of four children, being famous for having a girl in every port. To while away his lonely hours at sea he often had a shipboard female companion.

Hayes then conned his investor into equipping a ship for the China trade with Hayes as master. That was the last the investor saw of either Hayes or his ship.

Need it be said that this was neither legal nor Christian on Hayes’s part but would become almost routine and be the beginning of numerous international jousts with creditors and lawmen.

Another trademark ploy was to order provisions and to take on board a full cargo. Just as he was about to sail, the consignor would show up at dockside to demand his money. Hayes would cast off the lines and begin working his way out of harbour—with the by-now-frantic cargo owner still onboard.

Hayes then offered him the choice of being rowed back to shore and receiving his cheque in the mail, or continuing on to whichever port Hayes was destined for. Needless to say, the merchant invariably chose the former course of action then found himself whistling for his pay.

Another trick was to have his ship overhauled then skip port without paying. Or buying a ship with just a down payment, selling it at the next port and pocketing the entire proceeds.

He didn’t always get away with it. Declared bankrupt in Sydney, Australia in 1859, he was sentenced to debtors’ prison. Whether he bought his freedom by paying his bills isn’t stated. Another time, he borrowed money to buy the vessel Black Diamond, defaulted on the payments and sailed away with a cargo of coal. After the bailiffs caught up with him, he was on the beach once more.

But not for long as he was soon in command of the Shamrock, thanks to a wealthy and friendly Auckland widow.

The ladies obviously found him attractive; in 1865 he again tied the knot; the former Emily Butler would bear him two daughters and a son.

It should be noted that Hayes had something else going for him besides his cunning and a silver tongue; he has been described as being over six feet tall (then a rarity), weighing over 200 pounds and “big, bearded and blond”.

In other words, even in his stocking feet, Hayes was a force to be reckoned with.

As so often is the case with historical subjects, there are discrepancies in Hayes’s timeline, one source saying he first arrived in Honolulu in 1858. This doesn’t jibe with the Honolulu Advertiser’s retro-piece about his having rustled his neighbour’s horses in 1852. Whatever...

Over the years, Hayes’s financial and legal scrapes became legendary and, as so often happens in the case of desperadoes, some who knew him from afar began to see him as more of a lovable scamp than as a rogue. I mean, how could you look down on “the urbanest scoundrel that ever sailed a sea on evil deeds intent?”

Not all of his contemporaries felt this way, of course; in May 1868, when master of the brig Rona, it was reported that he’d been shot dead in the Fiji Islands. Unfortunately, it wasn’t so.

Besides selling guns to the Maoris (the Native Polynesian people of New Zealand) he turned to trading (perhaps we should say, raiding) in the South Sea Islands. Characteristically, he went about his business in his own fashion by robbing coastal outstations. He got away with it, too, for years, always a step ahead of the various international governments that held jurisdiction in the sprawling network of southern Pacific islands and atolls until a British Consul lowered the boom by having him arrested.

Ah, but I told you he was a charmer. He soon had the British authorities convinced that he was the injured party.

He did this in just three days!

And he did it so well that the British, whether from remorse at having arrested an ‘innocent’ man or just naivety, outfitted his ship and sent him on his way with their best wishes.

Things didn’t always go as planned; once, he was shipwrecked and he and his men only made it to Samoa by building a boat from his ship’s wreckage.

There were other ups and downs over the years; a high point occurred in 1872 when it was reported that he was in command of The Water Lily, said to be “one of the finest brigs in the island trade”. A downer was his arrest, only a year later, by an American warship for “piracy, slave trading and murder on the high seas”.

How he got out of that scrape isn’t stated. Said to be a subject of interest to the British, French and American governments, he carried on as usual and, in March 1874, experienced another shipwreck. Undaunted, he salvaged his cargo, set up a trading post and a harem of Native lasses.

In 1869, HMS Rosario seized the blackbirding schooner Daphne and freed its passengers. —Artist’s conception by Samuel Calvert (1828-1913) and Oswald Rose Campbell (1820-1887) - National Library of Australia, [1]State Library of Victoria, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3503946

HMS Rosario had also been ordered to investigate Hayes’s activities and spent three months looking for him. When it finally located him on Strong’s Island in the Fijis, he graciously piloted the warship through some reefs. However, upon learning that he was the subject of an investigation, he and a companion slipped away in a small boat.

Luckily, they were picked up by an American whaling ship and dropped off at Guam in February 1875.

While in Manila he was arrested for aiding prisoners to escape by selling them a schooner. Not so, said Hayes; they’d stolen it from him. Incredibly, he convinced a court of this and eventually received monetary compensation.

As it was the custom of that time for ships to report each other’s activities, Hayes achieved frequent mention in New Zealand newspapers for his “fresh villainies.” Among his many escapades of this period was his giving passage to escaped Spanish prisoners—only to abandon them to their fate when the authorities closed in.

No longer able to find legitimate cargoes or other respectable maritime commissions, he’d turned to one of the most reprehensible trades of all. Even the name has a nasty connotation.

This was the business of kidnapping South Sea islanders for sale as forced labour—virtual slaves—to sugar planters. Coercion through the use of false promises was sometimes employed and, considering Bully Hayes’s gift with words, may have worked for him for a time.

Initially, he’d invite the islanders who greeted his ship with fresh fruits and water to come aboard to trade. Then it was an easy matter for his armed crewmen to seize and shackle them for transport to a willing buyer. It was said that these tactics gave other blackbirders a bad name!

It’s as a ‘blackbirder’ that Capt. Bully Hates is remembered. In 1917 an unnamed former seaman described this trade, which operated between 1842 and as late as 1904, accordingly: “I don’t know who gave that business the name of ‘blackbirding,’ for we know it to be almost always downright kidnapping that generally ended in slavery.

“No wonder that natives resisted every recruiting crew that landed.”

Even though Hayes often changed ships, usually the unavoidable consequence of having them seized by his creditors, his reputation in the South Seas preceded him; indigenous islanders lived in constant fear of his arrival in their vicinity.

(He certainly moved about, historians describing his travels thus: Calcutta, Singapore, San Francisco, Australia, New Zealand (including British Columbia at least twice), Hawaii and the Caroline and Marshall islands, the Philippines, etc.)

Always, he lived by his wits. A 1911 biography described his split personality and prescience: “Merciless to those who opposed him, he had bursts of generosity unknown to his rivals. He recognized that the invasion of the South Seas kingdom [Hawaii] by the missionaries meant the coming of law and order, which, in turn, meant the death of his reign of violence.

“So he strove to thwart the proselyting, and until his end in the late [1870’s] with the Pacific as his shroud, he successfully combated the missionaries.”

Meaning that for almost 20 years Hayes had kept one step ahead of justice despite having achieved international notoriety.

Almost inevitably, there were those who defended him, at least to a point. In 1917, a Capt. Callaghan told the Hawaiian Gazette that “Bully Hayes was not as bad as nearly everyone says he was. He dealt squarely with men until he was cheated and when he was he became a very bad customer indeed.”

How ironic that he probably could have been successful in the arts, being known for his fine vocal renditions of German classical composers and for his accomplished performances with violin and piano. He even toured with a well known troupe in the U.S. while, at the same time, operating a hotel. All this ended when he impregnated the troupe’s leading lady. They lived for a time as man and wife although he was still legally married to a former widow in San Francisco.

Besides being fluent in several South Seas dialects, he spoke four languages.

But weigh those abilities with his career as a bigamist, swindler, pirate and blackbirder.

There’s further irony—perhaps justice is the better word—in how he came to his death in the Marshall Islands. On Sept. 26, 1877, the New Zealand Herald reported the “great rover and freebooter of the South Pacific” had come to an untimely end.

“...Capt. Hayes, while trading on a small vessel off the island of Jalmit, had a series of bickerings and quarrels with his mate and, while in the act of going down the [ship’s ladder] to reach his revolver to shoot the mate, was struck by him on the back of the head with the iron tiller, completely smashing his skull.

“So ends the life of this fearless pirate.”

Other sources state that the ship’s cook, supposedly responding to his captain’s threats, shot him or stabbed him in the heart; either way, Bully Hayes died on the spot, Mar. 31, 1877. He was 47 years old and his death, in the minds of many, was long overdue.

As the Herald cruelly put it: “The unlawful acts and deeds committed against property and society by this noted freebooter are very many...”

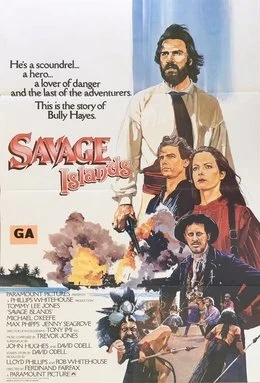

But he hasn’t been forgotten, having been the subject of books and newspaper and magazine articles—even a 1983 Hollywood movie, “Nate and Hayes,” starring Tommy Lee Jones.

The movie “Nate and Hayes” was also known as “Savage Islands.” Can you imagine a more likely subject for a pirate film than the rollicking Capt. Bully Hayes? —Savage Islands, a production of Phillips-Whitehouse Productions. - https://www.filmpostergallery.co.nz/product/savage-islands-nate-and-hayes/, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71246063

* * * * *

Most readers, I’m sure, will think that Hayes’s nickname Bully was most appropriate. Ironically, it’s not quite as it seems. The Wesleyan missionary Dr. Stephen Raybone gave him the title, ‘Bulli.’ Rather than describe him as a bully in the general sense, it’s the Samoan word for ‘elusive.’ A term with which Hayes’s many creditors would have agreed!