C.H. DICKIE: OUT OF THE PAST (Part 3)

by An M.P.

The author of this enjoyable memoir, Charles Herbert Dickie, obviously had as much fund recounting his colourful adventures as he'd had living them. (Family photo)

For most readers of the Chronicles this instalment of Charles Dickie’s colourful memoir will be much closer to home. After his all his wanderings and odd jobs in Michigan, California and Victoria, he arrives in the Cowichan Valley.

He becomes partners in managing Duncan’s first hotel, the ‘Miners’ and Loggers’” Alderlea where life was anything but dull. Fortuitously, his arrival coincided with the great copper strike on Mount Sicker, a short-lived boom that made fortunes for a few, set Duncan on the map and transformed Dickie’s career from that of an itinerant labourer to mining entrepreneur and politician...

CHAPTER IV

“Better the morning after than never the night before.”

I had become a Boniface. Another man and myself having a good business opportunity leased an hotel in a wooded part of the country [Duncan] that was destined to become a busy centre. When I wrote informing my parents that I had engaged in the liquor business, my dear old mother replied saying that she would have been as well pleased to hear of my demise and her judgment was good.

My partner was a big two-fisted splendid type of man, one of the finest characters I have ever known; being impetuous, he was sometimes given to acting first and thinking after. I, being more cautious and thoughtful, was different. It, however, was generally considered that we made a good team when complications arose, calling for the combined judgment of the firm.

The hotel had been run from the wrong side of the bar and time was required to convince some of our turbulent clients that the place was under different management. When we had our system perfected those who had idea that they could “lick the world” would...adjourn to the rival hotel kept by an Irishman and settle their grievances.

The first Sunday after we had taken over the place two men attempted to ride up to the bar on horseback. Their equestrian stunt proving a failure it was not repeated.

My partner and I were in the prime of life and we rather enjoyed the problems that at times confronted us and after a time it was possible for even a man with a monocle to walk into our bar and hand us his money without being insulted—while his money lasted.

Big, burly fighting loggers would arrive with a whoop and depart with a whisper. My partner and I were missionaries in a new field, and, as such, were at times respected. When business grew slack we would put another gallon or two of water in the whiskey or rum barrel. We had the only watered stock I have ever known where the more water the better for the purchaser.

Sometimes we went to extremes as perhaps my partner would neglect to inform me that he had been down the cellar irrigating, and I also realizing that things were quiet would do likewise. We have had inebriated individuals call in the evening to pay their respects and their offerings of cash, drink heavily all night, and to their surprise find themselves sober in the grey dawn. Some would boast of their drinking prowess, others became suspicious—to these we would dispense sundry drinks that would speedily kill suspicion.

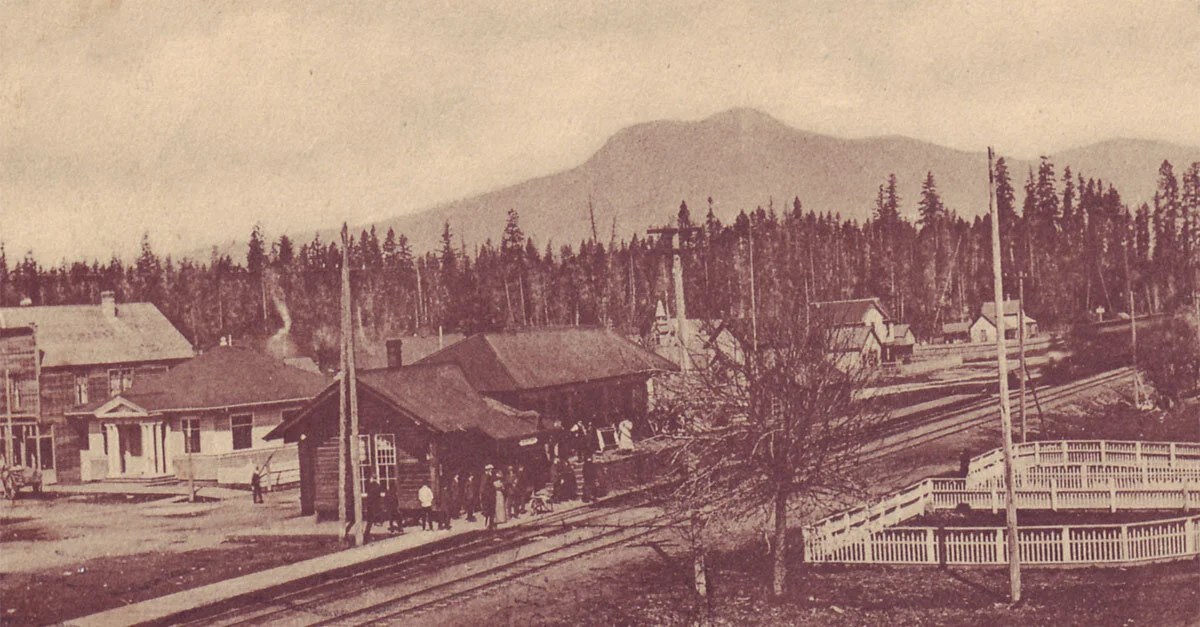

Duncan's Station, as it was then known, where Charles Dickie took up hotelkeeping with a "two-fisted" partner. It was here that he heard of a rich copper strike on nearby Mount Sicker and was offered the chance to swindle a man of his promising claim.

During meal hours my presence was necessary in the dining-room to prevent our boarders from throwing tough steaks at the Chines waiters.

Our hotel was a large wooden shell with shingle boarded partitions. This enabled the management to “keep tab” on all that was going on in all parts of the house. Complete supervision was possible and, at times, almost embarrassing. Our orchestra consisted of two fiddles, and I never hear a squeaky fiddle, but I see in my mind’s eye a long, low bar-room filled with tobacco fumes, poker and pool games running, big men dancing the Highland Fling and Double Shuffle, a red-hot stove encompassed by our guests and two big quiet men sauntering round keeping watchful eyes on all that was going on, at times nipping trouble in the bud, and at times after it had blossomed forth, keeping the machine running smoothly, the men in question being my big loyal partner and myself.

A sixty pound shot usually lay outside our bar-room door, and when a departing guest would lay his valise down to have a parting drink, under some pretext a friend would inveigle him to one side and when he returned to have “just one more” the shot in question would be reposing in his “grip”.

When the last spirituous farewell had been spoken and the train almost pulling out, the departing one would grab his valise to make a run for the train and the handles would usually come off.

At times the joke was varied by nailing the valise to the floor.

A bellicose client of ours received a sit of clothes from a tailor in the Capital City; the clothing not complying with specifications, the owner announced his intention of feeding the suit in question to the tailor. On the eve of his departure on his gastronomical mission an old sheepskin was substituted for the offending garments.

Upon the arrival of the gentleman at the tailoring establishment he discoursed at length before opening up his samples of tailoring duplicity. He arrived home with blood in his eye, but under the mollifying influence of the tranquilizing elixir we specialized in, the incident was closed until such time as some jocular person would sing out—“Come on, old sheepherder, and have a drink,” when tactfulness, on our part, was called into play.

I noticed that a long-armed man in our soirees usually preferred to stand diagonally opposite our stock of cigars, usually smoking a brand I could not recollect having served him with, and I gave the matter some thought. One evening I loaded two cigars and placed them where a man with a long reach could, if he wished, appropriate them.

The tall one leaned against the bar and I went out for a moment.

When I returned the gentleman in question was sitting by a window lighting a cigar; a moment after his hat was blown off and the window was broken by the impact of his head. I noticed later a slight increase in the profits derived from that brand of our trade operations.

A gambler in payment of his account made me a present of an ingenious piece of mechanism, the principle of which consisted of two rollers wound with a continuous strip of heavy silk, by turning a handle a piece of blank paper cut the size of a bank note, would be wound under the silk on one roller and a bank note, previously inserted, would simultaneously emerge from the other end of the device, which was artistically constructed and had several features added for the purpose of making the operation appear intricate.

I usually kept it loaded with new notes and at psychological moments my partner would ask me for some money to make change for a large bill. I would open the safe and take the machine our and place it on the bar in plain sight of all. I would cut a piece of paper the requisite size and feed it into the device and hand the money that came out to my partner, but the money would usually be refused by our customers.

To the wonderment of our Chinese help I would grind out weekly payments which with oriental cunning they would crumple up so it would not appear new.

One law-observing gentleman reported to the authorities that I was making counterfeit money, but I managed to retain my liberty.

We had a thin flask nearly filled with water in which floated a small ingredient, but with just enough air space and pressure left when it was tightly corked to cause it to float. The flask was then closed with a rubber cork. A slight pressure on the sides of the flask, which I always held during our seances, further compressed the contained air and caused the vial to sink to the bottom. When the pressure was released it again came to the surface. In the rubber cork, but not through it was inserted the end of a small rubber tube, and we called the contraption a lung tester.

Big broad chested loggers would blow into the tube until they were black in the face, but only at long intervals would I press the flask.

We had a little hunchback schoolmaster boarding with us. The little fellow always wore a hard hat at least one size too large. When it came his turn to have his lungs tested, he would inhale until he resembled a pouter pigeon. When he had blown until his hat settled down on his ears, I can see him now, I would press the flask and the little man would swagger. He became almost famous. By these and other simple devices we partly banished the monotony of what was, to my partner and myself, an uncongenial occupation, but pleasant memories respecting many of the great hearted, nature’s noblemen in the rough, who if needed would go to the limit for a friend, otherwise tough hard men, who were our patrons, still recur at quiet reminiscent intervals.

One Sunday afternoon a track-walker between the two hotels in the town arrived with despatches informing me that a big bad man was demonstrating at the rival hotel. It was also said that he packed a gun.

In case he might drop in, and on me, I exercised with the clubs and dumbbells, just to loosen up a little. He was soon on his way followed at a respectable distance by a gallery of pleasure seekers. Appreciating his intended visit and not to be outdone in courtesy, I went out and met him and imparted to him the information that I had a premonition that it would be in the best interest of harmony and would meet with my approval should he return to the place from whence he came, as a subdued and tranquil atmosphere was one of the attributes of, was an essential in my place of business, more especially on the first day of the week.

The big man seemed impressed by my arguments and, after telling me where I could go, he turned and left me, but not for long. I went back and took more exercise and when I next saw the impulsive one he was leaning up against my bar. My eyes sought a nice spot on his prominent jaw, as I asked him the reason why, when he stepped back and made a movement with his hand that I did not like. I hit where I looked and he went down and out. While removing him I went though his pockets but found neither weapon or money and I was sorry for hitting so hard. He was sure game as when he came around he was at me again. As it was getting turbulent, some busybody dug up the village constable and the troublesome individual was locked up.

After being held for several days to see if he was wanted elsewhere he was fined which fine I paid as I welcomed his absence.

A very prominent mining claim had been located not far from the sphere of our spirituous operations and I was all aflame with mining fever, and endeavoured to purchase an interest without success.

The owner [Harry Smith who’d already staked and sold the adjacent Lenora claim] of the claim...came to me one night and informed me that he had uncovered an outcrop of good ore on an adjoining property owned by a gentleman living in a small town “across the line” [Port Townsend, Washington] and that I possibly could make a deal with him; if so, he expected, for the information imparted, an interest in the claim. I did some high financing for I was almost “broke” at the time, and paid a visit “over the way” and having decided that a degree of circumlocution was advisable, I sauntered into a barber shop, knowing the value of these institutions as circulation mediums in a small town, and carelessly remarked that I had dropped into town to try and acquire a mining interest—not the one I was after—from a man I knew was not in town.

Having spread my net I retired to the principal hotel and awaited, as was described to me, a big one-eyed man who owned what I was after. He arrived on time and with our feet on a brass rail we discussed matters in general, with the exception of mining.

He treated me royally and after dinner we started out to view the sights. I took a liking to the man and he expressed a like sentiment for me.

There was some quality in the beverage we assiduously sampled that made for friendship.

Just before grey dawn I suggested that we call it a day—the gentleman asked me what I would give him for his mining claim. He was a good fellow. I could not be a rotter, so I told him the whole story, which further cemented our relationship. The gentleman then suggested that I would pay for the surface rights, a comparatively trivial sum, and he would give me a one-half interest in the property, his argument being that I being on the ground and a British subject, could handle the property advantageously.

We shook hands on it which was all we could do, as the saloons were closed and the next morning the agreement was signed, and having associated with other gentlemen with me we went to work. The property was afterwards known as the “Tyee Mine” which was capitalized at £180,000 in £1 shares and the shares of which went to 52 shillings on the London Stock Exchange.

There were, however, many anxious months before we knew that [we] had a mine, and when it had reached that status the control was with the English investors to whom we had, from time to time, to appeal for finances. We, however, did fairly well, and neither of us regretted the day and night I spent in Pt. Townsend.

The Tyee paid well for a year or so, and then the ore [began] to play out, but not before a profit of about a million dollars had been made.

A claim adjoined the Tyee on the east upon which I had cast a longing eye. I finally succeeded in acquiring it and at the 480-foot level we encountered high grade ore and the shares went skyward, but I was President of the company I had organized and I held onto my stock until things went wrong and I still have my shares. We made money fast with the Richard III, but never succeeded in locating a large body of ore, and in time closed down for lack of funds.

One factor or incident with respect to the mine I regretted above all others was: I had bonded the claim from a lady in Port Townsend, and when matters were looking well, I wired her to come over and see the property and have a talk respecting matters. She left on the ill-fated [S.S. Clallam] and she, and many others, were drowned in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

In the early sixties placer gold [had been] discovered at Leech River in the interior of the southern portion of Vancouver Island. Several thousands of miners flocked to the district and about one million dollars worth of gold was said to have been taken from the district. Two small but turbulent streams—when in flood, met head-on at Leechtown and caused a swirl that accounted for a large deep “pothole”.

Good pay had been found just above this hole and many people thought that sequestered in some part of it there might be found a concentration of the yellow metal. I did not at first think so, but after several trips the idea grew on me that I would like to exploit the pothole, so I associated with several with [several others] and we flumed both streams over the hole. After installing a ten-inch centrifugal pump we emptied and prospected the property and obtained fifty-five dollars which cost us fifty-five hundred, which was not so good.

I sometimes wonder whether I had not quit too soon. “T’is always thus in the pursuit of gold.”

(To be Continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.