C.H. DICKIE: OUT OF THE PAST (Part 4)

by An M.P.

The author of this enjoyable memoir, Charles Herbert Dickie, obviously had as much fund recounting his colourful adventures as he'd had living them. (Family photo)

Last week Charles Dickie recounted his hilarious days as the co-host of the rough and ready Alderlea Hotel, in what was then known as Duncan’s Station.

(Ah, the good old days, when men were men, the booze, sometimes watered, flowed free, the steaks were tough as leather and fist fights and crude practical jokes were the order of the day.)

Until the rich copper strike on Mount Sicker, Duncan’s (Crossing) had been just a quiet cluster of stores and businesses at the strategic intersection of Trunk Road and the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway that served as the Cowichan Valley’s commercial centre.

That changed dramatically with the Mount Sicker copper boom. Short-lived though it was, it produced millions of dollars in profits, mostly for English investors, but local merchants also prospered while it lasted.

As did our hero, Charles Dickie, who, as we’ve seen, made a tidy sum from his investment in the nascent Tyee Claim which, after he’d sold out, went on to become Mount Sicker’s richest producer.

With money in his pocket for the first time and, having divested himself of his hotel interests, with time on his hands, he looked about for something to do. A chance conversation set him on a fateful course to enter politics. This is where we resume his story as originally told in Dickie’s self-published (and now extremely rare) memoir, Out of the Past.

CHAPTER V

“I’ve had my share of mirth and meat and drink. ‘Tis time to quit the scene. ‘Tis time to think.”

It was one day suggested, by a friend whom I respected and who at least meant well, that I become a member of the British Columbia Legislature.

While I had always been averse to public life, I, after mature consideration, decided that an insight into parliamentary matters and ideals would at least prove interesting and would impress those for whom I cared with the fact that I was not entirely a nonentity.

I had never spoken in public and was not inclined to verbosity and when it was announced that I was to address, what I knew would be a large meeting, I had a chill and felt like taking to the woods.

That stormy political period, Joe Martin [Fighting Joe Martin was one of B.C.’s most outrageous politicians and premiers of all time] had soared into British Columbia, much to the gratification of the province of Manitoba, the people of which province had become weary of the political vagaries and activities of that politically turbulent gentleman. At the time of my debut into political life, party lines had not been drawn and the Government was composed of merely “ins and outs” and the burning question was whether or not Martin would preside over the political destinies of the province.

My very decent opponent was a follower of Mr. Martin, and with that gentleman was to appear at the joint meeting above referred to, and I was almost appalled at the prospect for Martin was eloquent and was a seasoned campaigner and I had a premonition that my first meeting would be productive of a killing feast that would mean “farewell, a long farewell to all my dreams of greatness”.

Having committed to memory what I, in my innocence, felt would be a convincing speech, I sallied forth to the tall timbers to see how it would sound.

While addressing a giant cedar the shade of which was appreciated, if not appreciative, I instinctively felt I was being overheard, and looking around quickly I saw an Indian peering at me from behind a tree with a look of amazement on his dusky countenance.

I blushed and informed him in “Chinook” jargon that I was sober and sane, which information was incredulously received and he, having lingered a while…glided away looking back from time to time.

After he had departed I attempted to resume my oration, but as a result of a doubtful conscience I imagined I was being overheard and my wondrous mental creation was still unsaid.

The great evening arrived and the hall was filled. My opponent spoke first and most briefly for, as a result of stage fright, his voice did not ring impressively, but he succeeded in informing the audience that he had nothing to say just at that time.

I noticed when he resumed his seat, a look of “All is lost” on Mr. Martin’s face.

When I arose and faced the audience I, for the first time, realized what was implied in the saying “weak in the knees”. My voice had a ventriloqual sound as if far off and I could see but one face, that of a critical old gentleman in the front row. I could not take my eyes off his face—I can still see it. I was about to bid the aforesaid long farewell to all my political aspirations and resume my seat when I noticed that my voice was getting stronger and apparently on its way back. The old gentleman seemed to regard me more kindly and my knees began to behave. The audience was mercifully spared my carefully prepared effort for it had passed entirely out of my mind, after a time, to talk commonsense, so my friends told me, when I had regained my senses.

I submitted reasons why Joe martin should not be the man of the hour and, in conclusion, I turned to that gentleman and assured him that it would be more pleasing for me to refer more graciously to a guest who was with us for the first time, but desperate diseases justified desperate and perhaps rude remedies.

Mr. Martin quickly rose and walked from the Hall and, as he was passing down the aisle, I thought his was the most beautiful back I had ever seen. I had achieved the reputation of being the only man in Canada who had driven Joe Martin from a political platform. It was not through fear but because of disgust that he quit the field. His candidate was disappointing while I was ably backed and cheered by friends of many days and in many ways. Martin simply thought, “What’s the use?” and quit.

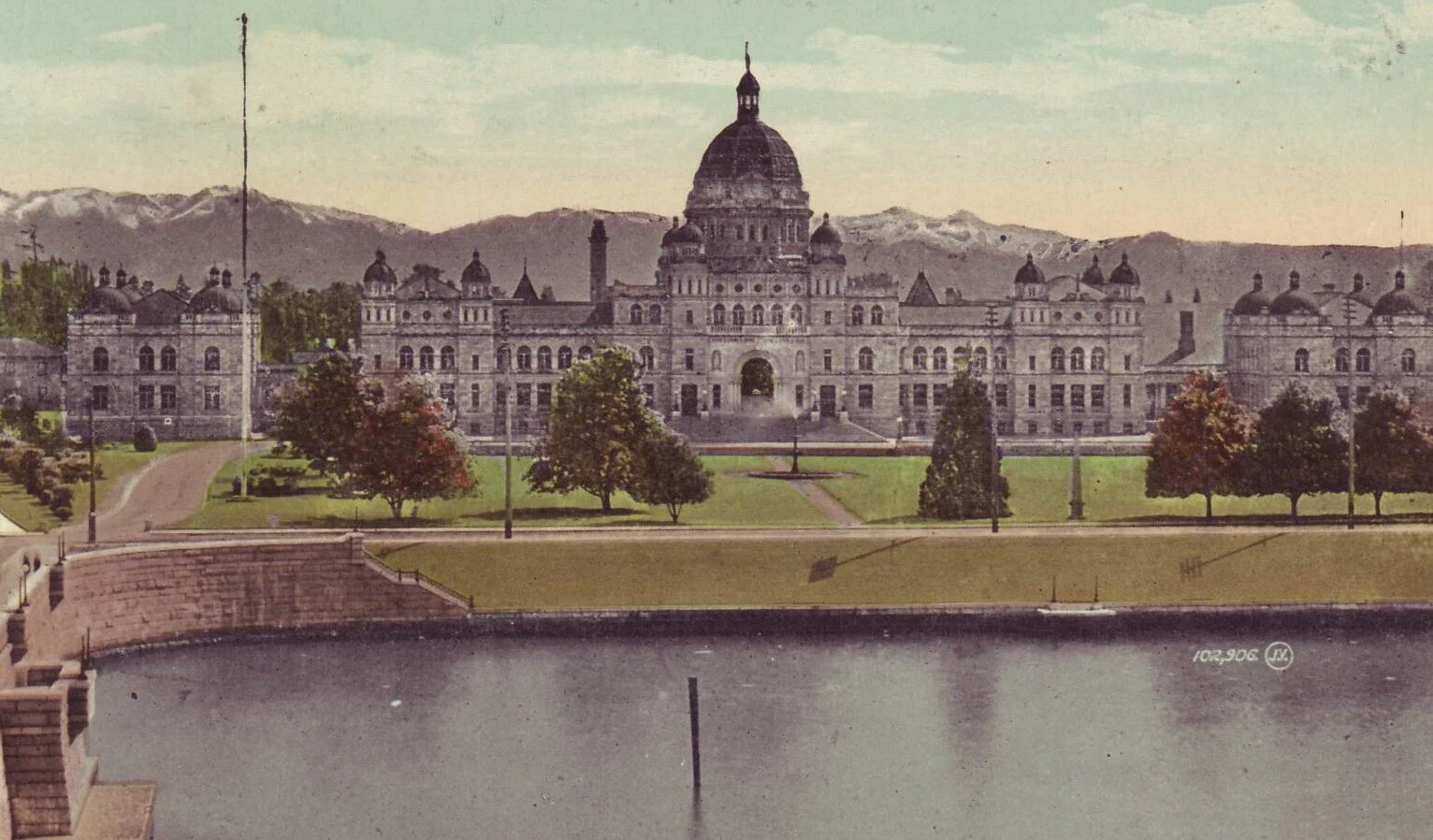

My election was a walkover and I found myself enrolled amongst the few who were in control of the destinies of wonderful British Columbia and I was proud—for a time.

The Martin forces had been routed and the question was, who was to be Premier. The province was in financial straits as the banks had refused further credits and a serious condition confronted us.

Up until this period political matters had been formulated, discussed and decided by the exclusive old Union Club in Victoria by a coterie of gentlemen who had done much for British Columbia and some things to it; also something for themselves.

New elements were projected into the arena of politics. Vancouver City was growing rapidly. The Kootenays had become prosperous because of great mineral wealth and representatives from those districts disputed the divine right to rule by what was virtually a “family compact” in Victoria and these gentlemen called for a new deal.

A convention of members elect was called at Vancouver and the name of Hon. J.H. Turner of Victoria, a lovable gentleman of the old school of culture and political thought, was put forward for Premier.

The name fell on reluctant ears of mainland members and the result, of the first day of deliberations, was most disappointing to those who wished for a stable government. Until late in the second day it appeared impossible to agree on a Premier, when a striking looking young man who had said little or nothing up to that time, arose and suggested as a compromise James Dunsmuir, our only British Columbia millionaire, be given the premiership for a year or until credit had been restored and order evolved from the existing chaotic political situation.

That young man was Richard McBride from New Westminster, afterwards to become Sir Richard, but affectionately and almost invariably referred to as Dick McBride. Dick was a picturesque, thoroughly western character, a good hearted fellow with a world of tactfulness, a man who, if he did not at all times say yes, seldom said no; the latter word was usually left to be said by his combative, capable, Attorney General Mr. [William] Bowser, a gentleman who did not strive for popularity and who administered, at times, the difficulties of his office fairly and absolutely fearlessly.

[Dickie is expressing his opinion here; McBride as premier and Bowser as attorney-general would become perhaps the most historically contentious of the province’s leaders—Ed.]

Sir Richard’s political career was meteoric and, it’s ending, politically tragic. The best loved of all political men in Western Canada [sic], he was relegated to the London Office [as the province’s official representative] and died away from the Province he loved so well.

James Dunsmuir had none of the qualities requisite in a leader of political thought and he, during his premiership, frequently remarked that he would prefer being down in one of his coal mines to being in Parliament. Dunsmuir gave place to Colonel [Colonel E.G.] Prior, a gentleman with Federal experience, but who also failed to bring about political stability, and it was borne on me that it was almost impossible to have satisfactory government unless Federal party lines were established, as, under the then existing conditions, any small group of members could hold up legislation.

Before going into Parliament I, in an unsophisticated way, had expected that I would find a band of devoted patriots, who would lie awake nights worrying over the problems of state. Instead I found a group of lovable gentlemen—ambitious gentleman—endeavouring to stay in power, and another estimable group trying to oust the former. Matters of state were of secondary importance and I saw a great light and tired of it all. When the next election came around I, being offered my seat by acclamation, declined the honour and again subsided to private life and rainbow chasing. Colonel Prior, because of a minor political indiscretion, was requested by Sir Henri[-Gustave] Joly, the Lieutenant-Governor, to resign and McBride was called to form a government. McBride established Dominion party lines, Liberal-Conservative and Liberal.

John Oliver, who had laboured relentlessly to unseat the Prior government, being a Liberal, was not eligible for a portfolio under McBride, so he transferred his animosity to that gentleman, who had previously been his patron saint. Oliver, reputed to be an honest man himself, seemed obsessed by the thought that all opposed politically to him were dishonest and his whole political career, for many years, was tainted by this unfortunate hypothesis.

Retired from the hotel business, with money in hand from the sale of his shares in the Tyee Mine, Charles Dickie was off to the British Columbia Legislature in Victoria as a newly-elected MLA. He was soon disillusioned with politics and, bitten by the mining bug, became active in mineral exploration in the Stewart River area of the northwestern province.

CHAPTER VI

“A mirage to keep us wandering in the desert.”

A syndicate of Mount Sicker miners had sent two of their numbers on a prospecting trip into the Portland Canal country, and, upon their return, with good reports and rich samples of ore, I was easily induced to acquire an interest in the claims staked. Upon visiting the property and arranging for a bond or two for adjoining claims, the Portland Canal Mining Company Limited was incorporated and development was proceeded with, and in course of time a concentrating mill was installed to treat the ore.

One sodden day in November we disembarked from a small tug-boat at the head of Portland Canal. I say we, for I was accompanied by a mining engineer who was to report on the property we were developing.

The mining claims, in question, were distant abut seven miles from the point of disembarkation and we, having engaged a big Norwegian to pack our dunnage, sallied forth expecting to reach camp in time for our mid-day meal.

My breakfast had consisted of a cup of coffee and, idiotically, I had neglected to take a lunch along. The rain had turned to snow or rather what was rain in the valley was snow on the mountain and we were soon waist-deep as we toiled upward, wet to the bone.

The snow was getting deeper as we climbed and to add to our perplexity, I had about arrived at the conclusion that we were on the wrong trail which, if so, was serious, as there was none other than our workmen on the mountain. I had been foolishly quenching my thirst with snow when, all at once, everything went black and I crumpled up on the trail all in, too weak to lift my head and all the time the pitiless snow was falling as it can fall in that region. The air was so filled with large flakes that, in the failing light, as the day had worn on, it was difficult to distinguish the falling snow from that which had come to rest.

I instructed our packer to go on for half an hour and if he did not locate the camp to return and perhaps they could drag me down the hill. I say perhaps. My companions, also dog tired, ineffectively tried to get a fire started while I lay unable to brush the snow from myself, and doing some thinking. I was anxious to make a mine out of the prospect somewhere ahead or elsewhere. I was not ready for the trail across the Great Divide and I could distinctly see a white-haired lady before the fire at home doubtless wondering how her life partner was getting along and then I fancied I heard a faint’ hallo’ and shortly after one of our workmen was pouring hot tea into me and the warm blood was once more racing through my veins. I staggered into camp and the next morning I was little, if any, the worse for my enforced rest in the snow the day before.

In later days when the mining property which we were inspecting was causing me almost unendurable brain worry, I frequently thought it would have saved me a lot of trouble had the Norwegian not found our camp.

My next visit to the property in question was on a broiling day in midsummer and, as I felt chagrined at the thought of having laid down on the trail on my previous trip, I decided to take a sixty-pound pack to the mine just to show “the boys” that I was not yet senile and useless.

The day, as I have said, was hot, hot as Hades. The trail was slippery! it was steep and the flies were worse than bad and the names I called myself for having started with a pack would not make respectable reading, but I could not leave the pack for that would have been a confession of weakness. So, resting from time to time, I finally reached a small stream just a short distance from camp. At this stream I tarried at length until I was rested up and then I pranced into camp like a two-year-old.

The Superintendent, when he lifted the pack from my back, told me I was a wonder. In my heart of hearts I knew I was a fraud.

When our mining project was at its best behaviour the mountain marmots would salute us with their startling whistling notes. The skies were blue, with erstwhile fleecy clouds, causing beautiful shadows to race along the mountain sides and I never failed to note the varied colourings of the foliage on the slopes and in the valleys of that most beautiful and interesting region, and one felt thankful for the lovely God-given world. “God was in His Heaven and all was well with the world.”

When the mine proved disappointing, under leaden skies, one stumbled along the trail wet to the skin, petulantly brushing away pestilential flies land mosquitoes. All hope seemed abandoned and the world seemed God-forgotten. Coolgardie Smith, a well-known character who had, at various times and places, been a gambler, lightweight fighter and an all-round sport and, withal, a good fellow, drifted into the district “on a shoestring” and through the exercise of executive ability was soon in control of a promising property. When all was at its best and the air castle of Coolgardie and myself were architecturally perfect we, with our feet on the brass rail, used to have long liquid heart to heart talks as to our plan of procedure when we had garnered in a few millions.

Coolgardie had an infallible “system” which, given unlimited capital, would make a roulette game look as easy as would a Baptist deacon to a shell game operator. We finally decided that when we had the capital aforesaid, we would saunter into Monte Carlo and put it out of business. The little gods that have to do with mineral deposits, however, did not play the game with us; they proved unkind. Our castles dissolved in thin air. Mediterranean shores were unvisited and doubtless M. Le Blanc, of Monte Carlo, never realized how near he had been to punching the clock and carrying a dinner pail.

When we made the first payment on claims we had under bond, one of the partners interested looked too long on the wine or gin when it was red or white[and] saw animals which were not of the fauna of the district. One morning we found he had gathered to his fathers and as there was a partly filled bottle by his side, we concluded he had died happily.

The remaining partner took unto himself a wife but their hearts did not for long “beat as one,” and one morning he informed his good lady—so the story goes—that he was going to drown himself. The lady was not excitable and, knowing her husband’s aversion to water, took the matter calmly. He bade her farewell and started on a run for the inlet looking over his shoulder, from time to time, to see if his wife was following. Something about the water that morning did not appeal to him and, when he reached the shoreline, he turned and ran alongside, but not in the water. Then retracing his steps he found, when he arrived back, that his wife had his breakfast ready for him.

Came a time, however, when he did not sidestep but placed a revolver to his head and blew his troubled brains away. Some carelessly say that he did not know the gun was loaded but. be that as it may, Joe McGrath, another picturesque, reckless character had crossed the Great Divide.

Another in the district who was beloved by all, was an Englishman of good family, with an Oxford education and not spoiled by it. One of nature’s noblemen and a man of magnificent physique, having made a small fortune and lost it and becoming enmeshed in the toils of the twin enchantresses Jamaica and Demerara, he played the game impartially and vigorously with both but, finally concluding that the game was not worth the candle…as did poor unlettered McGrath, he died by his own hand.

Dad Rainey was a pioneer of pioneers in the district and was also beloved by all who knew him. During the “boom” he made a fortune but, as with others, did not keep it.

Dad had a claim known as the “Franklin” on which he set much store, the wish doubtless being father to the thought that it would make a mine. One day he was found badly injured at the foot of a cliff he had fallen from. When he had recovered sufficiently to walk round, he was missed one day and later found dead at the foot of the same cliff—some said—but it is better to think he accidentally fell. I could lengthen the list of tragedies in that North Country, but it would tire my readers and it is saddening to me to recall them. The lure of gold, and tragedy, have ever gone hand in hand.

When Soapy Smith met his well merited desserts on the long wharf at Skagway, his gang was disbanded and several of its members drifted up Portland Canal, but their voices were not as raucous as before and they behaved as well as could be expected in an outpost of the Empire, where careless ideas prevailed. One member of the gang, a passable miner, worked in the Portland mine until he fell seriously ill. It was in the winter of the “deep snow,” well remembered by all who had been in the district. The miners having, with characteristic liberality, fed him all the medicinal supplies in camp, notwithstanding which he still survived, it was decided to get him to a hospital, and he was placed in a blanket and hauled over the snow seven miles to Stewart, where a launch was chartered to take him to Port Simpson.

It was a twenty-four hour trip, and none expected that he would reach the hospital alive, but Dan was not born to die thusly. He recovered, spent his savings and came back to work. A few days later he drove his pick into, what is known in mining circles as, a “missed shot”. The miners collected what they could of his remains and those of his Slavonian partner, and they were buried together. They had been friends in life; in death they were inseparable. The blood of the Slavonian was intermingled with that of Dan Moranville.

Stewart became a busy bustling western town. A railway was built up the Bear River Valley to the Red Cliff Mine. Wharves were constructed, capital flowed readily in and the pioneer prospectors disposed, in most cases, of their prospects for substantial sums and all went merry as a marriage bell.

The district, however, did not live up to its expectations, the mines proved disappointing and closed down. A pall of quietude descended on the district and Stewart soon became an almost deserted town. Some years elapsed when interest was revived [when] fabulously rich ore…was encountered in the old Bush Property which, after many vicissitudes, became the noted Premier Mine, and Stewart again revived and doubtless has a future.

In retrospective moments I look back with a feeling of sadness to my few years of unsuccessful endeavour and opportunities overlooked in that now attractive region but, “quien sabe,” I may again succumb to the lure of gold and fortune may prove more kind.

I continued at divers times and in various places to put down “damn-fool” holes in the landscape shaking dice, as it were, with the mountains, but with ill success. Every mineral deposit I worked on was wrong side up. The deeper I went, the leaner the metallic contents, so I decided it was advisable to take a rest and give my Jinx time to leave me. The old type of prospectors of the West was a peculiarly remarkable class of men, men in a class by themselves. They were so credulous that they would even hypnotize themselves.

A ridiculously absurd story, illustrating their credulity, their unselfishness in not keeping a good thing to themselves and to what length they would go in search for precious metal, has been told in all mining camps: An old prospector, having crossed the “Big Divide,” was informed by Saint Peter that Heaven was full and he was denied admittance. Being a wily old man and thoroughly versed in the psychology of his class, he devised means of making room for himself. Asking if he might speak to an erstwhile “pal,” and permission being granted, he imparted to his old chum that rich diggings had been discovered in Hell—but asked that it be kept quiet—then he went back and sat down on his pack with his back to a wall.

Soon after the Pearly Gates were opened wide and all the old prospectors in Heaven came trooping out, stampeding for the new field.

The old man picked up his pack and started to follow when he was hailed by Saint Peter and informed that there was now room. The old fellow said, “It might be so,” and kept on his way, true to the tenets of his class, willing to go to Hell in pursuit of gold.

Notwithstanding bitter disappointments, hopes and expectations dissipated, prostrate air castles and Dead Sea fruit—what a wonderful experience it was to have wandered through quiet forests and beautiful secluded valleys, to have climbed mountains and to stood, as it were, on the top of the world with some wholesome companion by our side, with ptarmigan mountain marmots, unafraid, almost at our feet with God’s blue sky overhead and the grandeur of mountains, snowfields and glaciers on every hand. Surely all this was an exemplification of the inevitable—at times inexorable law of compensation.

How pleasing it had been and what a tribute to nature to have noted the refining influence of glades in the forest primeval and of glorious mountain scenery, on careless erring humans, who under what we term civilized surroundings, would rarely utter a remark unaccompanied by an oath, would refrain from profane utterances and around the camp fire at night, in subdued tones, speak of days of old—of boyhood days—perhaps of wives and sweethearts, in the language of gentleman, perhaps in the rough—but of nature’s nobility, expressing thoughts in words of earlier, cleaner years before their lives had been tainted and debauched by wrong environment.

As old age creeps on one, when carried back by memory to these glorious days when in the full vigour of manhood and splendid optimism, whilst lured by the quest for gold, the thought arises that although the foot of the rainbow was not reached, it was a wonderful game and was well worth the candle.

I, at any rate, have a monument in the district that claimed my attention for several years. The Geological Survey Party, under that outstanding geologist McConnell gave a magnificent eternally snow-clad mountain my name. A kindly gesture, indicating substantial if not outstandingly intelligent efforts on my part, to beat the game in Portland Canal District.

(To be Continued)

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.