Che-Wech-i-kan’s ‘Dusky Diamonds’ Put Nanaimo on the Map

More than a century after he was immortalized in bronze, his honorary title is to be erased in the name of Reconciliation.

Ever-growing Nanaimo owes all to the Indigenous man who was hailed as the Great Coal Chief. —www.Pinterest

A cliche 140 years ago, it’s politically incorrect today.

Nevertheless it was meant as a tribute to the man who earned his place in Vancouver Island history as the true discoverer of the coal fields that put Nanaimo on the map.

So, when he died, ‘Coal Thyee’ (even the spelling has changed over the years) as he’d become known to First Nations and Whites, was off to, in the words of a newspaper headline, the Happy Hunting Ground.

Great Coal Chief, as he became known, (Che-wech-i-kan or Tee-a-Whillum or, as most recently given, Ki-et-sa-kun) was treated deferentially by the men of the HBC and as something of a celebrity by his own Snuneymuxw First Nation.

In later years he was honoured by the naming of central Nanaimo’s Coal Tyee Elementary School.

But that was then and this is now—he’s being demoted into anonymity because the Nanaimo-Ladysmith School District has decided to rename the elementary school. A leading contender so far is Syuw’eb’ct, meaning, “our traditions,” or “our history”.

Let’s begin with the school’s current website:

* * * * *

Coal Tyee Elementary School. —Nanaimo News Bulletin

Welcome to Coal Tyee Elementary

Coal Tyee, home of the “COUGARS” is a centrally located elementary school in beautiful Nanaimo B.C. Coal Tyee Elementary, opening in 1996, is one of the youngest schools in our district. Our school currently enrols 350 students from Kindergarten to Grade 7.

Coal Tyee is named after Che-Wech-I-Kan (Coal Tyee) an important First Nations gentleman in Nanaimo’s history. It is said that upon bringing the Hudson’s Bay Company to the abundance of coal found on Newcastle’s Island [sic[ he was given the name “Chief of Coal”.

* * * * *

This January, reported the Nanaimo News Bulletin, The Nanaimo Ladysmith School Board unanimously approved a motion to “rebrand” the central Nanaimo school “in order to align with district policy”.

The Board says that it’s being encouraged to rename the central Nanaimo school by the “school community” and by staff and parents. “I believe we have a responsibility to honour that, explore it and have those community conversations,” said education committee chairperson Tania Brzovic.

The board has promised “a significant amount of consultation as they decide upon a process and “who gets spoken with,” according to the News Bulletin.

School board chairperson Charlene McKay stated that SD68’s school naming policy is “well laid-out” but, obviously, the various parties now think the current name is no longer appropriate.

Why not? Because Ki-et-sa-kun, as his name is spelled by the school district, represents “collaboration between the colonial and Indigenous peoples”.

His having shown the Hudson’s Bay Co. the coal outcroppings that sparked the birth of a metropolitan city and 80 years of coal mining prosperity now shows him to have been not a pioneering hero, but “a tragic figure”:

“His interaction with the colonial peoples led directly to purposeful colonization of the area and destructive resource extraction that has impacted the land.”

In other words, if I’m interpreting this correctly, he “betrayed” his people and the environment!

Enough of this, let’s get into telling the story of Che-wech-i-kan’s rightful claim to fame and the founding of the Hub City as one of the province’s greatest coal producers and today, one of its largest cities.

* * * * *

Vancouver Island’s coal mining history actually began two years before, at the northern outpost Fort Rupert, which is a story in itself. Briefly: The Hudson’s Bay Co. had gone to great effort and expense to establish a colliery there but it failed on several points, including the accessible coal’s having been of a lesser grade, intense local Indigenous opposition and, as much as anything else, labour unrest.

To the extent that some of the “troublemakers” were ordered to be imprisoned and fed only bread and water.

As I said, it’s a story in itself and one for another day... So back to Che-wech-i-kan:

HBC trader Joseph William McKay was working in his Fort Victoria office when he was interrupted by the foreman of the blacksmith shop. A Snuney-muxw chieftain was in to have his musket repaired, he informed McKay, and as he’d watched the ‘smithies at work, he’d been impressed by their use of imported—not Fort Rupert—coal to fire the forge.

The workmen had smiled when he closely examined the fossil fuel in a bin. But they’d stopped their grinning when Che-wech-i-kan casually mentioned that he knew where there was plenty of black stone near his Protection Island home—he often burned it in his campfires.

Hence the shop foreman’s hurried visit to McKay’s office. After interviewing the man, McKay, with all the largesse for which the HBCo. was infamous, promised him a bottle of rum and the free repair of his musket if he’d bring samples of what McKay hoped was coal to Victoria.

Winter came and went, and McKay assumed Che-wech-i-kan had forgotten his promise and all but dismissed the matter.

But, come spring, he paddled his coal-laden canoe into Victoria’s Inner Harbour. He’d been ill, he said. When the fort’s blacksmiths forge-tested his samples and pronounced them to be of excellent quality, McKay was instructed by Chief Factor James Douglas to proceed to Winthuysen Inlet, at “Naymo.”

There, almost at water’s edge and near the future site of the Malaspina Hotel, McKay’s party examined an outcropping of high-grade bituminous coal.

Che-wech-i-kan was “suitably rewarded” and became something of a celebrity among his own people. He also became known for his uniform of top hat, frock coat and trousers (the former with its brass buttons, the latter with their equally-prominent knee patches).

To the dependable McKay fell the task of overseeing the beginning of what was to become a major industry and set Nanaimo on the course to city-hood.

Actually, it wasn’t that simple. His employers having spent and lost a small fortune on the coal prospects at Fort Rupert, Douglas was reluctant to commit them to further expense on Nanaimo’s untried coal seam. So he sent McKay off on another assignment while he awaited instructions from the Old Country.

All this occurred in 1851. The following year, Douglas, who’d been promoted to Governor of the Crown Colony of Vancouver island, paid a personal visit to the potential mining outpost. During this “excursion,” his men examined three coal seams. The upper seam was three inches thick, the middle seam 20 inches, and the lowest seam almost five feet thick.

(This certainly compared well with Fort Rupert coal which had also been exposed on the surface but in shallow and fractured seams that almost defied systematic extraction with the men and means available.)

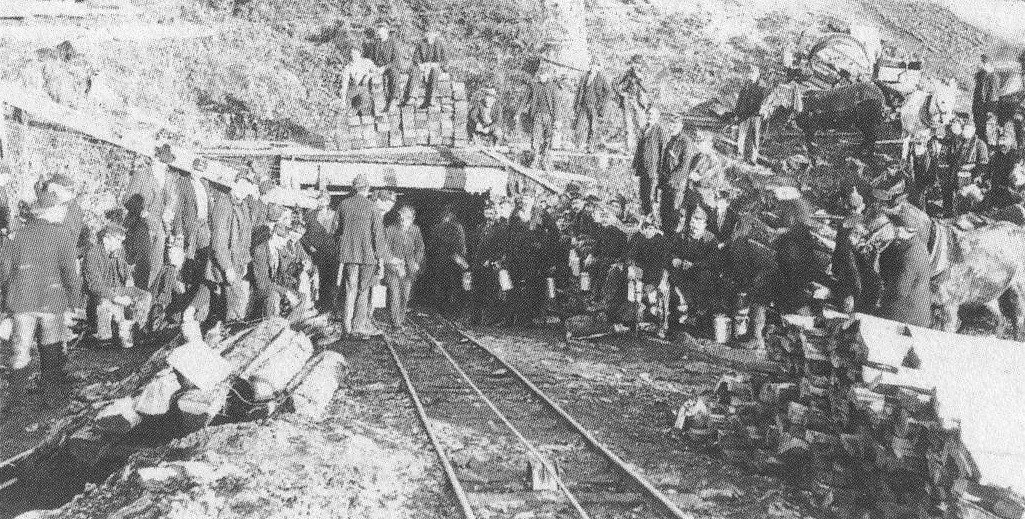

It got even better. With “the assistance of the natives,” the HBC miners dug out 50 tons in a single day—at a cost 10 pounds paid in goods to the obliging Snuney-muxw.

The famously unflappable Douglas wrote to his superiors, “The discovery has afforded me more satisfaction than I can express.’ High praise, indeed, from old ‘Square Toes’!

Now convinced of the site’s coal producing potential, Douglas ordered McKay to take formal possession of the site “with all possible diligence,” which he did, Aug. 27, 1852.

(This had long been the home of the Snuney-muxw, it should be noted, but this was colonial B.C., remember.)

Thus began, with the arrival of Fort Rupert veterans John Muir and John McGregor and a handful of miners, 80 years of prosperity and the digging of millions and millions of tons of coal. The so-called black diamond employed generations of miners and their families and made a handful of mine owners fabulously rich.

(Today, the iconic Nanaimo Bastion and a simulated underground tunnel in the city museum recall the city’s black past which has become legendary over the years. And all of it thanks to the man who’s now remembered as Che-wech-i-kan—the Great Coal Chief.)

Many years ago I wrote in one of my first books, Ghost Town Trails of Vancouver Island, how the first small contingent of professional miners set up shop with hastily built log cabins, a store and a wharf. And how, within two weeks of McKay’s claim of possession of the land for his HBC employers, they made their first shipment of coal—480 barrels—to Fort Victoria via the company schooner Cadboro.

With all their other duties in getting established, they hadn’t actually dug the coal out of the ground but, with the help of the Snuney-muxw, had simply picked the coal from exposed seams in the ground.

—Wikipedia

Next on the agenda was the building of the Bastion and the naming of the new community, Colviletown in honour of HBC Governor Andrew Colvile.

Already, ships, including those of the Royal Navy, were filling their holds and bunkers with Nanaimo coal; this necessitated the need for more miners and the importation of 24 skilled workers and their families from Staffordshire. With their families, they totalled 72 men, women and children upon their arrival on the famous Princess Royal.

Nevertheless, much of the surface mining work was done by the local Indigenous population, particularly the women, who loaded their canoes for transport to ships waiting in the harbour from coal carried in their skirts.

Already, too, the town’s nondescript houses and buildings were described as being “remarkably sooty,” a reference to the growing film of coal dust that covered everything, including the vegetation.

A sure sign of progress in the Industrial Age if ever there was one.

Initially, the coal was so close to the surface that there was no need to sink shafts; when that did become necessary, the coal was hoisted to the surface by windlass. It would be years before an underground (and underwater) maze of shafts would extend for 10s of miles and 100s of feet down, and require powerful steam plants to provide ventilation.

By then, too, there were numerous competing mines, not the single and primitive operation begun by the HBC which had sold its colliery interests to the Vancouver Coal Mining & Land Co.

What a deal: 6200 acres of land, the coal beneath it and everything on it, from houses to machinery, workshops, a sawmill, wharves and barges—in effect, all of Nanaimo Harbour itself, including Newcastle and Douglas (Protection) Islands.

There was even a coal deposit on Newcastle Island.

As early as 1862, just a decade since Che-wech-i-kan’s tip that there was plenty of the black stone that burned near his home, the white population of Nanaimo had grown to 300 and coal production to 18,000 tons annually. This would pale alongside the production of later years.

Gone were the days when coal had to be imported at great expense and inconvenience from the Old Country. Now there was abundant coal, thanks to the Wellington, Douglas and Newcastle seams, and most of it superior to that mined in the Bellingham area. Good enough to exhibit at the World Fair in London and to feed the hungry market in San Francisco.

The mines multiplied and expanded their areas of operation, Commercial Inlet was filled in with mine waste, Robert Dunsmuir started on the road to amassing the biggest fortune and achieving the most influential position in the province.

And all the while, Nanaimo prospered and grew and grew and grew.

Today’s Wellington was a separate and independent community when Dunsmuir made his first great strike; now it’s a Nanaimo suburb. Now, in fact, northern Nanaimo is on Lantzville’s doorstep and is expanding to the south.

The discovery of coal in what’s now Nanaimo led to the founding of the neighbouring communities of Cassidy, South Wellington, Extension, Lantzville and, over time, Cumberland, away up north in the Comox Valley.

—Author’s collection

It was the combination of world-wide Depression and the advent of oil that eventually precipitated the Island’s coal mining demise. Nanaimo’s No. 1 Esplanade Mine and the Nos. 2,3 in Extension, the biggest mines with their 100s of jobs, closed in the early 1930s. King Coal—King Midas for a lucky handful of successful industrialists—was all but dead.

But it had been a great run while it lasted—80 years—and all thanks to the sharp eye and keen mind of a man who’s been remembered as Che-wech-i-kan, the Great Coal Chief. A man whose just claim to recognition is now is under siege...

* * * * *

So much for history. When, in February 1881, Che-wech-i-kan died, he was thought to be about 75 years old.

In fond farewell the Free Press marvelled at all that had transpired in little more than a quarter of a century: “What mighty changes has civilization made in this district, since ‘Coal Tyhee,’ in a blanket perhaps, poked around the beach in what is now the City of Nanaimo and discovered the dusky diamonds that have made her famous throughout the world.

“The primeval forest has given way to macadamized roads, the stately buildings and the magnificent works of the Collieries. While the screech of the locomotive whistle is now heard, where the hungry growl of the wolf and the purring sound of the panther reigned supreme.

“May the old man enjoy rich pastures and overflowing streams of pure water in the happy hunting grounds of his kindred, and may his camp fire never be extinguished.”

I would add, “May his name never be extinguished.”—TW

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.