Come Hell or High Water, the Mail Went Through in the Old Days

“...Owing to my loose parka filling with water and shooting me up again as quickly as I went in, I was not seriously wet.”–Tom Tugwell.

In my recent caption for the coming Christmas Chronicle, I sort of joked that, thanks to email, hardly anyone mails Christmas cards any more, with or without an envelope.

It wasn’t always so, of course. For more than three-quarters of a century Christmas cards were mailed in western world countries by the millions each November-December. But that’s all changed now.

One can argue that digital technology is to blame. Why use “snail mail” when you can send and receive an email anywhere in the world in a matter of minutes? It’s much less personal than a card but... But.

I believe there’s more to it than that, however. Mail delivery as I knew it from childhood through middle age or so, was—or seemed—to be much more of a bedrock Canadian institution; something that people trusted, used and relied upon without a second thought.

Long before the internet and couriers we had ‘posties’ in uniform going their rounds with their black bag hanging over their shoulders, the red boxes at strategic intersections, daily (well, Monday-Friday) home deliveries. Not only rock-solid dependable but inexpensive.

Have you mailed anything lately? Did you suffer sticker shock?

In short, times have really, really changed. That old expression, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds” is pure nostalgia now.

But it was that way once, when B.C. mail went through, come hell or high water, sometimes at the risk of the carrier’s safety, even his life.

* * * * *

First it was the iceman. Then the bread man, the milk man, the Rawleigh Products salesman, the Chinese green grocer, and others who delivered to or solicited us on our very doorsteps. Now all are gone, victims of changing times.

How ironic that mighty Canada Post’s home delivery should ultimately be brought down not by the physical challenges of moving mail across one of the largest nations in the world with one of the more challenging landscapes, but by the economics of decreasing volumes of mail because changed technology has spawned cultural choices.

It was, perhaps, as inevitable as was the phasing out of the once-ubiquitous telegraph and, almost, the hard-wired telephone.

Once, the Canadian postal service relied upon men (for the most part) who literally defied hell and high water, sometimes both, to deliver the mail. Theirs was a sacred trust, one that they seldom failed. If you don’t believe me, read on.

Sooke pioneer Tom Tugwell’s story is remarkable enough in itself, but don’t think for a moment that he was unique. Canadians embraced responsibility and duty more willingly and to a much greater degree than do most of us spoiled come-latelys. (Another of those changing times things, this one a negative, alas.)

A century-plus ago, the notorious Fantail Trail was the tenuous link between northern B.C.’s Log Cabin and Atlin. Over these 40 miles were shipped all freight and His Majesty’s mail, usually by dog team. If all went well, it could be accomplished in a day. But seldom did all go well, as mailman Tom Tugwell knew personally after eight years’ of fighting the elements.

For $90 a month and board, I might add.

In 1908 he described one such trip over the Fantail, and it’s an eye-opener today. He and an unnamed helper reached Atlin, then scene of a gold mining boom, two days behind schedule after having struggled through temperatures between -20 and -30 degrees F.

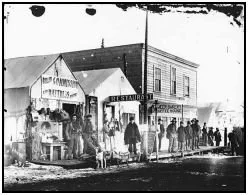

Gold rush era Atlin in northern B.C. — http://atlinbc.com/atlin-business.html

Once, their heavy sleigh broke through the ice and Tugwell had to jump into the freezing water to rescue the mail. When, after a 17-hour rest, supper and breakfast, they tried rowing the two miles back across Atlin Lake, they found that, in the teeth of a north wind, with both having to row and unable to steer, it was hopeless.

“We decided to...get a man to cross with us, but none were willing, so we remained there until the next morning... Meanwhile a bank clerk stationed at Atlin who was anxious to get out for the Christmas holidays, wanted to come with us, but would not make the trip without his trunk.”

At first Tugwell refused to take the 150-pound trunk.

But the bonus of having another man help cross the lake made him relent and they set out. It took them five hard hours, “with the steam rising from the lake. It was very cold and the water quickly freezing...and we were covered with an inch of frost on arrival at Taku, which we reached at 6:10 p.m.”

Next morning, they skirted ice to Golden Gate where they’d left their canoe, to find that someone had used the craft and carelessly abandoned it in the ice so that it was frozen fast. Meaning that they had to chip it free with their hatchets, haul it to the water’s edge, several hundred feet distant, where it again stuck.

So they hitched it to the dog sleigh “with a long rope which we made fast to the dog harness some distance ahead. The passenger’s trunk was hindering us and we had to drag that along the shore to the open water and place it in the boat. With the three dogs hitched to the boat and sleigh, I left my partner to drive the dogs and went ahead, and he urged the dogs from the rear, and I calling them from the front, so as to hurry them and keep them moving, so as not to allow them to stop and break through the ice.”

They made only 50 yards when “through she went, the dogs stopped and the boat and the sleigh both went through the ice.

“[I] also went through, but owing to my loose parka filling with water and shooting me up again as quickly as I went in, I was not seriously wet. I continued the journey as quickly as possible after we rescued the boat and sleigh, to prevent myself from freezing, and finally we were successful in getting the boat and the sleigh to the open water, where we made a start for Kirkland’s [roadhouse], with the water freezing on us fast.”

The sun is shining in this winter scene but it gives some idea of the wintry conditions that Tom Tugwell and his companion faced while delivering the mail to Atlin in 1908. —atlin.jpeg

Then came two miles of “hard rowing” through ice. Upon landing a mile from Kirkland’s, Tugwell ran ahead to change into dry clothing as a relief party helped his companions. After a hot meal and night’s sleep, they reached Teepee next day. By then a storm was brewing and they warned their passenger that to continue was at “the peril of his life”. He confidently replied he was game and they were back on the trail by afternoon.

Six miles later, the storm broke, burying the thin trail and making it necessary for one to forge ahead through drifting snows. Having recovered the eight dogs they’d left on the trip in, they fought onward, Tugwell acting as guide, his partner in charge of a team, the passenger directing the second.

Within eight miles, however, the clerk was “continually falling down from fatigue.

At last he fell at intervals of 100 yards. I kept shouting to him and urging him on again and again. Time after time he arose and continued, buoyed up against defeat because he had been positive he could make the trail, and also from his desire to get out for Christmas.

“Finally his endurance gave out and...he fell for the last time and was unable to rise again. He just lay there, played out and waiting for the storm to go over. He would have waited several years if we had let him.

“I pulled him to his feet and tried to keep him moving so he would not freeze, but he was unable to stand and fell down again, quite willing to lie on the ice forever. We hitched all the dogs to one sleigh and laid a canvas on the mail, spread the passenger on top and lashed him to the frame. Telling him to keep his feet and hands knocking together as he lay, we drove those dogs as hard as we could.”

Dumping the hated trunk into the snow, the couriers raced on in the darkness. Their original trail had been obliterated, their only lantern was broken, but they floundered through five miles of driving snow to Log Cabin where their frigid passenger revived in time to catch his train the next afternoon–after they’d retrieved his trunk!

Thus ended, in the words of Tom Tugwell, “an ordinary trip over the Fantail Trail”.

* * * * *

Tom Tugwell, the heroic mailman just described, came by his hardihood naturally. His father had served briefly in Her Majesty’s Navy before taking his discharge in Victoria in 1858 to accept the job of conducting a census of the Island’s west coast inhabitants.

That duty almost killed him, a story in itself, but he survived to become a respected hotel keeper in Esquimalt. Business at his Bush Tavern apparently prospered for, in June 1869, it was reported that he’d leased the Crown Hotel, also in Esquimalt and said to be “most pleasantly located and fitted up with special reference to the accommodation of families and travellers. Meals can be had at all hours.”

But misadventure continued to dog his footsteps. That December, a mysterious early morning fire razed the two-storey structure. According to those first on the scene, the blaze could have been extinguished with a bucket of water. But no water had been forthcoming and the flames soon roared out of control.

Several off-duty sailors braved the inferno to save most of the furnishings.

Two fire engines were dispatched, and bluejackets from Her Majesty’s Ships Charybdis, Sparrowhawk and Boxer also joined the battle. Unfortunately, they arrived in time only to prevent the flames from spreading to adjacent buildings and docks.

“The hotel,” reported the Colonist, “was in the occupancy of Mr. Tugwell, who was absent at the sale of his property on Esquimalt Road...when the fire broke out. The origin of the fire is clearly traced to a defective stovepipe. A fine piano, being lowered to the ground, fell and was smashed. The inhabitants of Esquimalt request us to return their sincere thanks to the officers of H.M. Fleet and their crews for valuable service rendered, without which a great portion of the town would have been laid in ashes.”

The mystery as to the fire’s origin deepened when it was reported that there had been no stovepipe in the room where flames were first detected. More puzzling was a missing box of jewellery; Mrs. Annie Cox, a boarder, had kept $1100 in silver plate and jewels beneath her bed.

When the fire was finally extinguished, the hotel in smouldering ruin, her treasure had vanished.

The bluejackets who’d stripped her room of furniture and accidentally dropped her grand piano two storeys, denied having seen a box and a careful search of the debris yielded no clue. Ironically, Mrs. Cox had insured her valuables for $1500–but the policy had expired three days before.

The Colonist was inclined to view the fire as accidental although “it is just possible that the box was abstracted by a thief and the place fired to hide the theft”. Police investigation did, in fact, uncover a sailor’s misappropriation of a book belonging to Mrs. Cox. The “hardened sinner” had grinned joyfully when sentenced to three months.

The next day, Tugwell and his bartender, William Young, were charged with arson, police claiming they’d fired the hotel by soaking furniture and carpets with coal oil. At the preliminary hearing, officers produced several articles salvaged from the hotel which reeked of the volatile liquid. According to their evidence, rooms remote from the fire had smelled of oil and much of the hotel’s furnishings appeared to have been removed earlier.

The constables further revealed the fact that Tugwell had recently ordered two cans of coal oil and, when the blaze had erupted, barkeeper Young had shown “great indifference and apathy”.

Mr. Cox, husband of the victimized boarder, testified to having heard “mysterious movements about the house late at night, and a noise as if some person was cutting through a partition and removing laths and plaster”.

Also entered as evidence was Mrs. Cox’s treasure chest which had been found–empty.

Final link in the chain of circumstantial evidence was the remarkable premonition of one H.E. Wilby, who’d accompanied Tugwell to the sale of his previous property. Wilby, who’d “been impressed for some days with the belief that a fire would break out at Tugwell’s,” had instructed his wife to send a messenger by horse if fire erupted during his absence!

The court wasted little time in returning a charge of incendiarism, indicting Young as principal, Tugwell as accessory before the fact. Inspector Bowden placed the astonished pair in a cell for the night.

Brought before the bench next day, Tugwell’s application for bail was denied and the trial proceeded slowly. On December 14, a boatman named McKinnon testified that he’d been one of the first on the scene and had rescued furniture from the flames. As for the smell of coal oil on certain furnishings, he said he’d been carrying two lamps down a ladder when a sailor bumped him, breaking one and spilling its contents over an easy chair and other pieces. Tugwell and Young were remanded eight days and released on sureties of $500 each.

When they again faced the magistrate, it was to claim that a servant had started the fire while clearing hot ashes from the stove. The magistrate replied that, so far as he was concerned, the fire was “most mysterious”. Finally, two months after the blaze, Tugwell and Young were discharged, “no evidence to fasten the crime upon them” having been produced. A family account, it’s worth noting, accredits the failure of the hotel venture to a smallpox epidemic.

Tugwell became Otter Point’s first settler and ultimately inspired the naming of Tugwell Creek.

For six years he worked the land, a stage service between Sooke and Victoria, and the Sooke post office. Precisely six years later it was reported that a gilt eagle which had adorned the lost steamship Pacific’s wheelhouse had drifted ashore near his home. Then Mrs. Tugwell who’d been ill for some time, died: “She was a kind-hearted, good neighbour and her loss is deeply regretted by her name friends.”

In June 1896 Tom Tugwell was again in the news with his notarized statement that members of the Liberal Party had attempted to bribe him to obtain secret documents belonging to the Conservative campaign headquarters, of which he was an organizer. The charges and counter-charges and name calling made for a bitter federal campaign. That’s when he headed north to the Yukon but illness forced him to discontinue prospecting and he opened a roadhouse at Log Cabin with his son, Tom Jr. About 1903, he retired to Victoria where he died two years later, aged 67.

Tom Tugwell Jr. continued to operate the Log Cabin Hotel and, as we’ve seen, a hazardous mail run over the Fantail Trail. He died at Ucluelet in 1958 where a son, Bernard, later served as justice of the peace.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.