Cowichan War Chief Tzouhalem: Legend Reborn?

Cowichan’s legendary Tzouhalem is in the news again.

Not the Quamichan war chief himself—he’s been dead for well over a century—but the fact that he's going to be the subject of a movie.

Reporter Robert Barron recently reported in the Cowichan Valley Citizen that documentary filmmaker Harold C. Joe, a member of Cowichan Tribes, and a film crew are making a television documentary that will “examine the near-mythic figure of Chief Tzouhalem through interviews and creative re-enactments".

The operative word here is “creative” as the only existing written records that refer to Tzouhalem are the hand-me-downs of non-Indigenous (i.e. white) contemporaries (some of them in positions of authority and therefore adversarial).

Meaning that Tzouhalem is seen today through a racially and colonially tinted lens—the very lens that’s now under critical scrutiny across Canada.

The recent tsunami of re-examining the history books—and in some cases rewriting them—appears to be gaining momentum. In many cases it’s long overdue. In the case of Chief Tzouhalem, it will be interesting to see what the filmmakers make of the career of a man who went from tribal outcast to tribal hero to declared outlaw and murderer.

As Leslie Bland of Less Bland Productions puts it, “We’ll be investigating Chief Tzouhalem’s history and the legends around him, and we’ll also be exploring how his story came to us.

“Did it come to us from the colonists' perspective, or from the voices of the First Nations?"

Bland promises the documentary will be “a critical examination of the stories” and will include “accounts of his life and times from First Nations, elders, and historians".

The documentary will be broadcast on CHEK-TV and Super Channel following a theatrical release.

* * * * *

Today's Green Point, Cowichan Bay, where Chief Tzouhalem had his own island stockade and followers, is a narrow fringe of privately owned waterfront homes. All very peaceful on an Autumn afternoon.

Next to Mount Prevost, it’s our most prominent and recognizable landmark, greeting visitors as it does from the Malahat north and dominating the Cowichan Valley horizon from three points of the compass.

That’s Mount Tzuhalem–as it’s spelled (probably in error, but in governmental stone nonetheless) by our official Ottawa bible of geographic features, the Gazetteer of British Columbia.

Locally, of course, we prefer to throw in an ‘o,’ as in Tzouhalem Road. Whichever is the correct spelling, they both owe their origin to the Cowichan war chieftain who, a century and three-quarters ago, held deadly sway over friend and foe alike. When finally he met his downfall it was at the hands of his own people.

Even more so than usually is the case of bigger than life characters, Tzouhalem’s story is incomplete, contradictory and confusing. Where to begin?

The first known record in which he is mentioned by name (albeit with variation in spelling), is in a letter written in October 1849 by the Rev. Robert Staines, schoolteacher at Fort Victoria. ‘Tschellum’, Staines wrote, was a Quaw’cutch-un (Quamichan) Cow-itch-un (Cowichan). Thirty years later, in recounting the time he was in charge of Fort Victoria for historian H.H. Bancroft, Roderick Finlayson mentions Tsough elam, “a Cowatchin Chief”.

They were both referring to Tzouhalem, the man. Tzouhalem the myth undoubtedly owes his elevated status to Charles Hill-Tout, a self-taught anthropologist who made nothing less than a comic book super-hero of our Quamichan/Cowichan bad boy. His Tsoqalem, “the Cowichan Monster,” was a foot taller than most men, with a long, thin face and a tread “as soft and stealthy as that of a mountain lion,” who could run like a deer. One day, while living alone in the woods, he met a “hairy forest monster,” who, with his wife and children, were feasting on a boy they’d killed. They graciously invited him to join them. He did, thus adding cannibalism to a growing resume of black deeds.

As a parting gift, the friendly Sasquatch jabbed him in the eye with the bill of a hummingbird, so that he should be able to see as well by night as by day.

Thus armed, Tzouhalem became the terror of the district, “waylaying and robbing anyone who crossed his path,” and hiding in his cave on a mountain. All of this is according to the romanticizing Hill-Tout.

An amalgam of somewhat more down to earth, albeit equally questionable, versions has it that Tzouhalem was born at Khenipsen (Khinepsen) during a thunderstorm, that his head,“misshapen and ugly,” was too big for his body, that he was epileptic, probably mad and mean as a wolverine. We know nothing of his father, only that his mother, who was Cowichan (Hul-qumi-num), was killed by the Haida, and that Tzouhalem swore to avenge her. This ‘perfect storm’ of vendetta, physical deformity and/or mental condition is accepted as having motivated his legendary blood lust and anti-social behaviour.

Some believe that, when still a youth, he was banished from his own tribe and took up residence in a cave that was said to have been formerly occupied by a Thunderbird (a giant mythological bird large enough to carry a whale in its talons), on the prominent mountain that would come to bear his name. It is recorded that, as an adult, Tzouhalem attracted a number of young rebels to his side and built his own fortified stockade near Green Point, at the entrance to Cowichan Bay. This would have been during the 1830s and ‘40s when the northern Haidas raided as far south as Washington State and Tzouhalem was among those who met the challenge. As the Cowichans’ war chief, he won several battles and partially redeemed himself in the eyes of his people.

He came to the notice of whites in June1844.

Fort Victoria had just been built and, overall, the men of the Hudson’s Bay Co. had been getting along well with the local Songhees tribe. Enter Tzouhalem. One day, while checking out the Europeans and their fort, he and some companions spotted their first oxen and horses. So much bigger than deer or elk–so fat, so sleek, so many more steaks!–were these creatures that placidly foraged in the brush and meadow lands outside the stockade.

Tzouhalem and his promptly men slaughtered several of the beasts.

Furious, Chief Factor Roderick Finlayson accosted the Songhees Chief Tsil-al-thach. Years later, he recalled: “...When it was found that the natives killed some of our oxen feeding in the open spaces, I then questioned the Songees [sic] chief about this and demanded payment, as we could not allow our cattle to be killed in this way with impunity.”

Insulted by Finlayson’s accusation that his men were responsible, Tsil-al-thach “went away in a rage, assembled some Cowichan Indians to his village and the next move I found on their part was a shower of bullets fired at the fort, with a great noise and demonstration on the part of the crowd assembled threatening death and devastation to all whites.”

Finlayson, just 26, had taken command of the new trading post just a few months before. But he was no greenhorn. While in charge of Fort Durham on the Taku River—“as dismal a place as could possibly be imagined,” as he once described it—he’d faced down an Indian attack. Years after, he recalled how he’d armed his men, manned Fort Victoria’s bastions and kept his men inside until he could settle the matter.

Singling out Tsil-al-thach’s lodge on the shore of the Inner Harbour (at the foot of today’s Johnson Street), he ordered his half-caste interpreter to go to the chief, pretend that he’d deserted his white employers, and tell him that Finlayson was going to “fire on the chief’s lodge and to see that all the inmates had left it in order to prevent bloodshed, and to make a sign to me, at the same time watching matters from the bastion, by twisting his handkerchief round, that all was vacant, which he did.”

A nine-pounder loaded with grapeshot was aimed at the lodge.

Primitive as was this muzzle-loading carronade, when Finlayson gave the order to fire, his gunners were bang-on. The cedar-planked house flew “into the air in splinters like a bombshell”. For several minutes, as the Songhees howled in astonishment, he worried that several had been killed and was “quite relieved when the interpreter came round and told me none were killed but much frightened, not knowing we had such destructive arms”.

A deputation of chieftains soon appeared at the fort gate. Assuming a “warlike attitude,” the trader told them that unless they paid for the cattle that had been killed he’d “demolish all their huts and drive them from the place”. That same day, restitution was paid in furs, hands were shaken, a pipe of peace was smoked, and Finlayson said that he hoped that it was the end of “this disagreeable affair”.

That night, the chiefs gathered to discuss the day’s dramatic events. Tzouhalem was unconvinced. Perhaps it had been a trick or just blind luck. Could Finlayson do it again? It was agreed to test him and, next day, they asked “in an amicable way” for a further demonstration. The trader obliged them by firing a cannon ball at an old canoe in the harbour. Not only was it another direct ht, but even more impressive as the ball kept going, skipping across the waves and into the forest beyond.

“What happens next is not at all clear,” historian Charles Lillard wrote of Chief Tzouhalem in a 1997 newspaper column which carried the headline, “Big as life and twice as mean”.

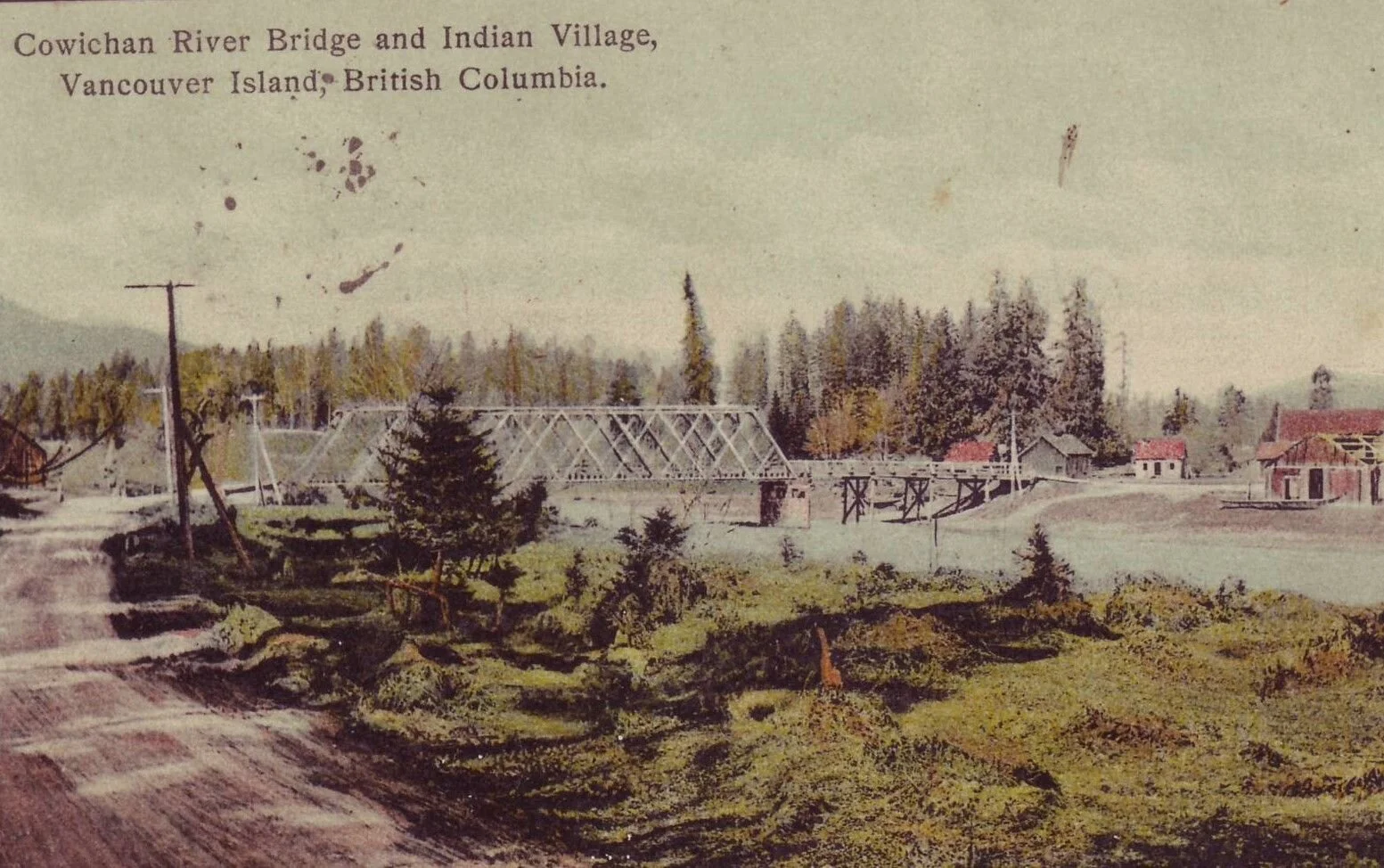

A 1920s postcard view of Duncan's 'white bridge' and the Allenby Road Reserve where Chief Tzouhalem reputedly was born.

Who, today, while shopping at busy Duncan Mall, realize that this was Somena Village, birthplace of the legendary Chief Tzouhalem for whom one of the Cowichan Valley's most identifiable landmarks is named?

After his cattle-killing debacle at Fort Victoria, perhaps he lay low for a while. “It seems he becomes a pirate and attracts a small [body of] like-minded young men. Robin Hood he isn’t. Tzouhalem at one point has 14 wives, most of them widows of men he’s killed...”

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

It’s known that he had his own stockaded fort beyond Cowichan Bay’s Green Point and his own followers. At one point, the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s Chief Factor James Douglas referred to him as the highest- ranking sub-chief at Quamichan.

Five years after his humiliating confrontation with Roderick Finlayson, Tzouhalem is back in the area of Fort Victoria and again making trouble. In October 1849, the Rev. Robert J. Staines wrote, “Two murders have taken place close to us since we have been here. But the colony is in such an infantine state at present that nothing can be done to vindicate the laws. The first was committed by the Songass [Songhees] upon a lad, a nephew of a chief of another tribe living on the east side of the Island, called the Cow-itch-uns [Cowichans] and that particular family of them are designated as Quaw’cutch-uns [Quamichans].

“This was to avenge a murder previously committed by the lad’s uncle upon a Songhass. This fellow...by name Tschellum [Tzouhalem] is a determined bandit, who has 10 or 12 followers, and commits depredations upon all around, but chiefly upon those who are at variance with his tribe, though they themselves are said not to acknowledge him, and to term him an outcast or outlaw from their tribe...”

This was immediately followed by a second slaying in the Christmas Hill area of Saanich where the HBCo. had a farm.

A young Clallam assisting the dairymen was “pierced by five balls, as he was standing over the fire. There is a wood [forest] within a few yards of the spot. The men, who were close at hand, rushed into the wood, but could see nobody. Men went out to pursue on horseback, but could find nobody. One man they saw, who escaped into the woods. However, it was by some means known to be this man.”

He’s referring to Tzouhalem.

The Clallams were determined to have revenge. Over the next two days they and their allies organized an expedition of 140 men from as far as what’s now Washington State, then known as the Oregon Territory, and proceeded by war canoe to Green Point, Cowichan Bay, “the fellow’s dwelling [Rev. Staines continues] which is a stockaded fort, built upon an isolated rock, surrounded by water”.

A small party landed under fire but were quickly driven back to their canoes, leaving one of their wounded who “entreated his companions to fetch him off, but they dared not, so the besieged made a sally and cut off his head and the assailants came away, having effected nothing. The headless body was brought here two days after by some women to whom it had been committed...”

Tzouhalem obviously won that exchange. He wasn’t as successful in his attempt, while visiting Fort Langley, to ambush Chief Trader James Murray “Little” Yale.

Once prominent provincial historian B.A. ‘Pinkie’ McKelvie, who took a great interest in First Nations history, described Tzouhalem in the most colourful of terms, referring to him as “Tzouhalem the Wicked, the bluebeard of the Cowichan, who emerged from his fort at Cowichan Bay, where he kept his many wives, to plunder and kill.”

McKelvie thought that Tzouhalem would have succeeded in assassinating Yale had not one of the trader’s men seen him waiting in ambush. Instead, Ovid Allard crept up behind the war chief, wrestled him to the ground and confiscated his musket then—quote—“booted him down to the beach to his canoe. He never returned to Fort Langley.”

Speaking of McKelvie, I have in my archives a photocopied, unsigned manuscript bearing the simple title, Tzouhalem. It cries out B.A. McKelvie, the foremost provincial historian of his day who retired to Mill Bay and died in 1960. Besides innumerable newspaper and magazine articles, he wrote several books on B.C. history, all of them based upon extensive research and, thanks to his contacts made over his years as a journalist, include firsthand accounts by many of those involved. He has been a gold mine for succeeding writers and historians although some of his writings would fail to pass the recently raised bar of standards being set today.

Several nuggets in the manuscript have all the McKelvie earmarks.

Unlike those accounts which have Tzouhalem born at Quamichan village, this version states that he was born, “in all probability, during the last decade of the 18th century, at a spot which is within a stone’s throw of the present city of Duncan. A little to the left of the fairway leading to the first green of Cowichan Gold Club [he’s describing what’s now the Duncan Mall, not today’s golf course south of Duncan], and about 70 yards from the tee, there stood an Indian house in which he first saw the light of day...”

McKelvie—I’m going to stick my neck out and accept that he’s the author—is referring to what once was the large Somena village, now reduced in size, that straddles Allenby Road.

An intimate detail such as this is just the sort of intangible McKelvie would have known because of his long personal acquaintanceship with both founding nations of the Cowichan Valley.

In almost super-villain terms he describes Tzouhalem as having been of medium height and slender build with “a hideous head, much too large for the rest of his body, which gave him a rather grotesque appearance,” and joins other historic writers in condemning the war chief as “a cruel monster, a cold blooded cutthroat murderer...the veritable scourge of the Pacific Northwest...

“From Seymour Narrows to the north, to the southernmost extremity of Puget Sound, from the west coast of Vancouver Island to a point a hundred miles up the Frazer [sic] River, the Indians lived in fear and trembling of Tzouhalem and his band of Cowichan raiders.”

McKelvie accepts that Tzouhalem did have his virtues: “He was courageous, he was enterprising and possessed great initiative. He had brains, he was essentially a self-made man, and all that he was came to him as a result of his own endeavours. He was not a hereditary chief, but proved himself a born leader of men.”

For all his fierceness, however, Tzouhalem’s empire was rapidly crumbling. The white newcomers actively discouraged inter-tribal warfare (it was bad for business) and backed it up with overwhelmingly superior firepower. This meant that, because he was no longer needed as a war chief to protect the Cowichans from enemy tribes, he could no longer maraud and plunder at will.

Once again, he became a tribal outcast with his wives and few followers.

Speaking of his wives, he was supposed to have no fewer than 14 of them at this point in his career, all taken by force from their husbands who, if they resisted, were killed.

He could be equally hard on his unwilling women. When a Snuneymuxw ‘widow’ tried to escape from his harem, he permanently lamed her by burning her feet.

Another wife, acquired by trade in exchange for Tzouhalem’s promise not to make war on a fellow Quamichan chief, made the mistake of taking a talented wood carver for her lover.

Tzouhalem, learning of their affair, commissioned the unsuspecting young artisan to carve the support posts for his Green Point lodge. Upon their completion, he lamed his wife by slashing the soles of her feet then threw the carver’s severed head into her lap “for a plaything.

Beryl M. Crier of the pioneering Shawnigan and Chemainus Halhed family, in her three-volume Indian Legends of Vancouver Island, tells how Tzouhalem, for all his wives, began casting covetous eyes at Tsae-Mea-Lae, a handsome Lamalcha who lived with her husband Schelm-Tum and family on Penelakut (then Kuper) Island.

Having so many times before won his brides by intimidation or, when necessary, murder, Tzouhalem anticipated little difficulty in adding her to his harem as he paddled across Stuart Channel with his brother, Squa-Lem.

He obviously had little concern for the Lamalchas’ established reputation as warriors.

Landing at the beachside village, he marched up to the lodge of his intended bride and loudly declared his intention to take her away with him.

At the sound of his voice those in the lodge fled but for Tsae-Mea-Lae who hid behind the door.

As Tzouhalem, finding the lodge apparently empty, turned to leave, Tsae-Mea-Lae, who has been described as large and powerful, and as quick-witted as she was brave, crept up behind him.

Catching him round the neck with a big clam stick, she screamed for her husband. Schelm-Tum, racing to her side, raised his Hudson’s Bay axe high.

A moment later, the head of the mighty Tzouhalem lay on the floor. Schelm-Tum made sure of his deed by cutting out his victim’s heart. It added to Tzouhalem’s mythical status because it was said to be “small as a salmon’s, and black as soot”.

To add insult to injury, the Lamalchas sent his head back to Quamichan but buried his body in an unmarked grave on Penelakut Island.

Cowichan Bay's Khenipsen Road is another link with Chief Tzouhalem. It means "seized by the neck" in Hul'qumi'num.

They immortalized his death by naming a village at the northern end of Galiano Island, Porlier Pass, for his home village, Khenipsen, which means “caught by the neck” or “caught in the neck”. Today we have Cowichan Bay and Green Point’s Khenipsen Road.

There’s another version of Tzouhalem’s downfall, which one historian has dated during the winter of 1854 (another says 1859). Apparently even his own brother had tired of his erratic behaviour and, as they’d rested on a beach at the northern end of Saltspring Island, Squa-Lem secretly disarmed his musket.

When Tzouhalem attempted to shoot Tsae-Mea-Lae’s husband, it misfired, giving her the opportunity to pinion him against a post with the clam stick and thereby enable Schelm-Tum to deliver the coup-de-grace.

Legend has it that the dreaded Tzouhalem was born during a hurricane and that the day his head was returned to Quamichan, the Valley was rocked by another great storm, “the like of which had not been seen in years,” hence the return of his head to Quamichan to placate the war chief’s raging spirit.

It’s said that, at one time, the macabre memento was known to be in the possession of “Old Bill Qualmatzilock, “a son of one of Tzouhalem’s old warriors, and himself as a boy a member of Chief Tzouhalem’s band”.

Certainly his legendary status has not dimmed over the years, one historian having even accused him of cannibalism and possession of “strange otherworldly powers”.

Even without the aid of a television documentary, Chief Tzouhalem has achieved international fame (or notoriety). Years ago, a Seattle mayor was made an honorary chief by a tribe from another state. Although they spelled it differently, the name bestowed on Edwin Brown was Tzouhalem, whom they described as having been a mighty warrior known and feared throughout the Pacific Northwest.

It’s not stated whether Mayor Brown was apprised of Chief Tzouhalem’s other propensities.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.