Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree’ (Part 2)

As we’ve seen, two men were pivotal to the events leading up to the Cowichan Valley’s only recorded hanging.

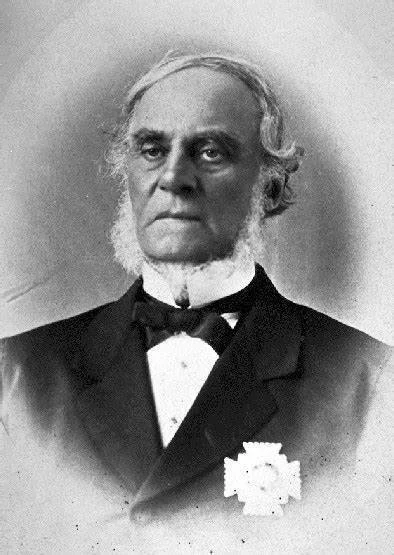

The first one is well known; in fact, Sir James Douglas is remembered as ‘the father of British Columbia’.

Fur trader, colonial governor and “statesman” Sir James Douglas. —www.biographi.ca

Such can’t be said of Tomo Antoine, the phantom-like Iroquois-Chinook woodsman whose skills as an interpreter, scout, guide and spy were essential to every major exploration of Vancouver Island and naval police expedition in the 1850s.

He has become provincial history’s ‘invisible man.’

Which isn’t to say that he didn’t leave his own indelible mark on Vancouver Island history even if it has, for the most part, been forgotten.

* * * * *

Almost from the time of the arrival of the Hudson’s Bay Co. on Vancouver Island with its founding of Fort Victoria in 1843, Tomo was set to work scouting out the lands and inland waterways and getting to know the First Nations tribes that occupied them.

This is where his interpretive skills shone brightest and he soon established himself among the southern Island tribes as their liaison with the white newcomers and their desirable trade goods. At the same time, he watched and listened and learned, to the extent that he became known as Chief Factor Douglas’s eyes and ears outside of the palisades of ‘Fort Camosun.’ Which explains some historians having added spy to his resume.

Others sugggest that Tomo wasn’t just cunning but almost Machieavellian because he was able to convince some Indigenous people that he was a demigod possessed with magical powers when they served his purpose.

Whatever the case, there’s no denying his value to the HBCo. Although unable to read or write he could draw accurate maps and, to quote the website, Leechtown History, “he could give the names, locations and numerical strength of the various Indian bands and describe the physical features of a land that was slowly giving up its secrets”.

In April 1850 Douglas commissioned him to escort Father Honore Timothee Lempfrit to Cowichan Bay where the French Oblate performed 2000 baptisms in a month. Then Tomo acted as interpreter for Bishop Modeste Demers; a role he seems to have taken beyond mere interpretation by (according to Demers) “teaching [the Cowichans] hymns and prayers in their own tongue”.

By 1851, when James Douglas had forsaken fur trading for governorship of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island, the loyal Tomo Antoine had become even more indispensable in his role of interpreter and guide as exploration of the Island was being pushed ever farther afield.

It appears that his first real police duties came in November 1852 with the murder of Peter Brown, an HBCo. shepherd at Christmas Hill.

(This tragic tale has been told numerous times over the years, myself included, in Cowichan Chronicles, Volume 3. But it bears repeating in condensed form as part of Tomo Antoine’s story and as a foretaste of the tragedy that would later lead to what become known as Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree’.)

The descriptions of two Indigenous suspects by another shepherd prompted Gov. Douglas to take personal command of the investigation. Although Tomo isn’t mentioned by name, based upon what we know of how Douglas employed his abilities, we can safely presume that he was the governor’s man in the field.

When Douglas informed the colonial office in London that apprehension of the murderers was “a measure absolutely necessary as an example to others,” he was referring to the entire Indigenous population, not just the Cowichans. Should the latter reject his offer of a reward and his demand that the perpetrators be surrendered, he wrote, “I shall be under the painful necessity of sending a force to seize upon the murderers”.

Within days, a Cowichan chieftain called at his office to apologize for Brown’s slaying and to assure Douglas that one of the suspects (the other was from Nanaimo) would be given up for trial. But he warned that there’d likely be resistance from the man’s own band, the Clemclemalits.

Douglas was relieved. But a month passed without further word from the Cowichans other than a report that the suspect who belonged to that tribe and who’d admitted to the killing had convinced his friends that Brown’s death was justified because he’d “insulted” the men’s wives.

So Douglas was informed; his pipeline had to be Tomo Antoine.

Thus it was that Capt. A.L. Kuper, when asked to lend his 36-gun frigate Thetis to bring the alleged murderers to justice, readily agreed for the “security and benefit of Vancouver Island”.

(I remind readers that, as noted last week, colonial authorities did make use of superior military force to maintain law and order when the first Europeans were vastly outnumbered by the aboriginal populace. This was done to, in Douglas’s words, “alarm the Indians and prevent further murders and aggressions, which I fear may take place if the Indians are emboldened by present impunity.

“Every exertion will be made to avoid hostilities and to bring the Indians to a friendly compromise... [If] the Queen’s authority be speedily respected the tribe will be neither molested nor attacked.”

Again, Tomo Antoine has to have been in the thick of negotiations with the Cowichans who apparently had reconsidered surrendering the accused tribesman but had again been dissuaded by his family and friends.

Briefly: On Jan. 4, 1853, a heavily armed flotilla consisting of the boat crews of HMS Thetis (which was considered to be too big to navigate in restricted waters), the smaller RN sloop Discovery and the HBCo.’s steamer Beaver sailed from Fort Victoria.

In charge of 140 marines, seamen, Voltigeurs (militiamen) was Gov. Douglas himself. Upon arrival at Cowichan Bay, he sent word (via Tomo, no doubt) to the chiefs to parley with him aboard the Beaver; they agreed to meet at the mouth of the Cowichan River.

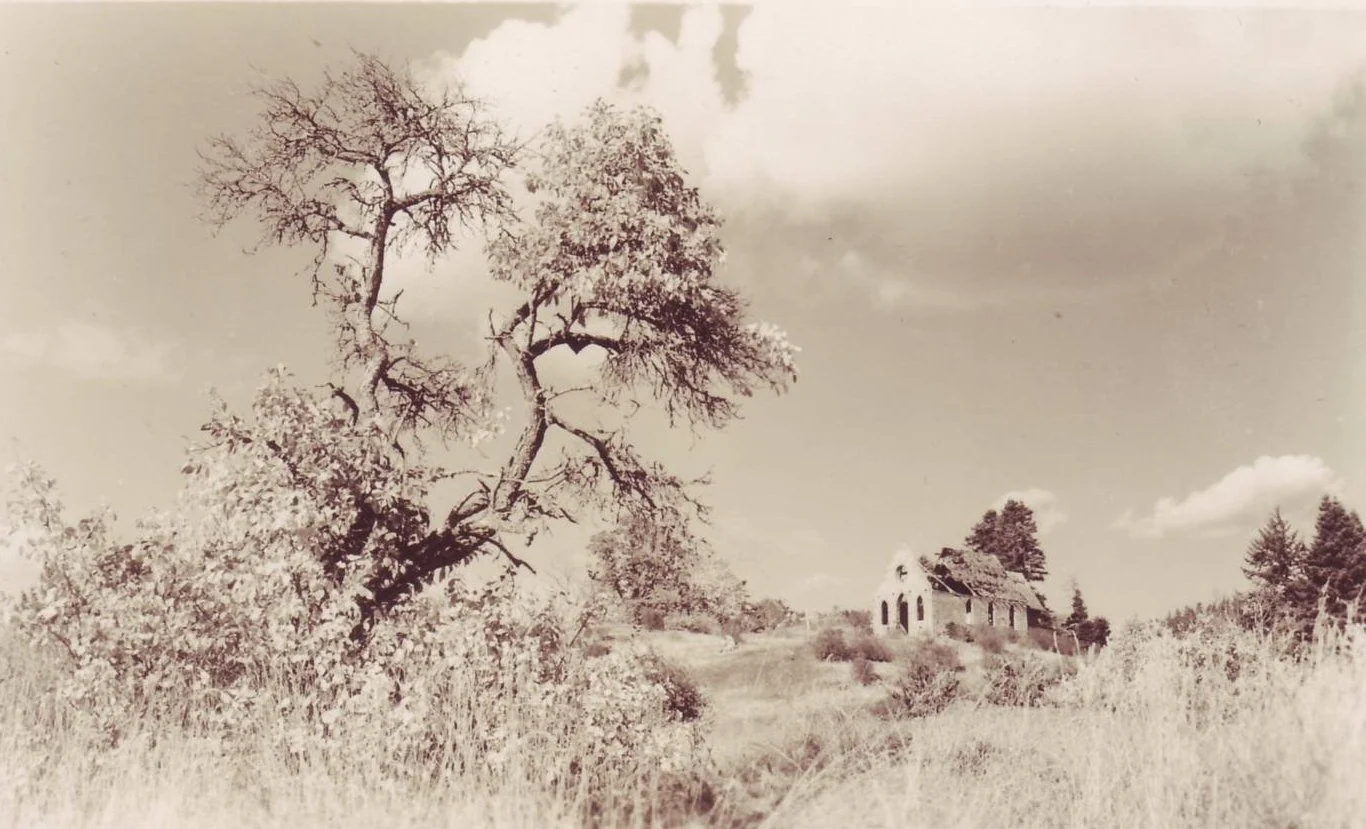

Next day, on a “pretty rising oak ground,” (Comiaken Hill, the future site of Fr. Rondeault’s Old Stone/Butter Church), the police expedition was met by an estimated 200 armed Cowichans, including the wanted man and his family.

Father Rondeault’s abandoned Butter Church atop Comiaken Hill where the province’s first naval police expedition confronted 200 hostile Cowichans to demand the surrender of an accused murderer. —Charles Worsley postcard from the author’s collection

Douglas later claimed that “their demeanour was so hostile” that he’d had difficulty in restraining his marines from opening fire.

There’s much more to this story but we’re following the career of Tomo Antoine. Our sources for what happened next are Douglas’s reports to his superiors and the memoir of a young naval lieutenant and later admiral. Simply put, Douglas appears to have defused the confrontation not with bullets but with words—by giving a speech!

“Hearken, O Chiefs!” he began in their own language. He could only have done this with Tomo Antoine’s able assistance. The result was astonishing. The Cowichans began to argue among themselves; hours passed as the bemused whites warily watched and waited.

Finally it was settled and the wanted man was turned over to the expedition by his own father. So Douglas and Lieut. Mayne professed to believe, anyway, as it’s now accepted that the Cowichans offered a slave in place of the real culprit.

Then, as the Cowichans watched “in the best possible humour”—Quote!—the prisoner was placed in irons and taken aboard the Beaver which carried on to Nanaimo and, after a pursuit (ergo Chase River), the capture of the second suspect.

On Jan. 15, 1853, on board the Beaver, both prisoners were tried before Vancouver Island’s first jury, made up of the police expedition’s naval officers. Despite their pleas through an interpreter (Tomo?) that the victim Peter Brown had it coming because he insulted their wives, they were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang on what’s now Protection Island’s Gallows Point.

(I leave it to readers to assess the fairness of a trial that was conducted without defence counsel before a tribunal of Royal Navy officers.)

Originally named Execution Point, the southern end of Nanaimo’s Protection Island which is now Gallows Point, serves as a grim reminder of British Columbia’s first murder trial, conviction and execution. —lighthousefriends.com

No doubt oblivious to the irony of his words to the sullen Cowichans, Douglas reminded them that “the whole country” was a British possession and promised to treat them with “justice and humanity...so long as they remained at peace with the settlements”.

Hostile opposition to the British authorities or criminal behaviour, however, would “expose them to be considered as enemies”.

The tragic ‘Cowegin’ case, Douglas concluded in an official note, “may be considered as an epoch in the history of our Indian relations which augurs well for the future peace of the Colony”. He was pleased with himself. Without bloodshed or firing a shot he’d, in his view, established British authority over the Cowichans whom he considered “the most warlike tribe on Vancouver Island”.

A reference to the use of ‘Iroquois guides’ to track the Nanaimo suspect suggest that Tomo Antoine served as more than an interpreter on this first naval police expedition. It certainly wasn’t his last. Nor, for all Gov. Dougla’s hopes to the contrary, would it be the last time that the Royal Navy would be called upon to carry out the new law of the land.

But these challenges would come later.

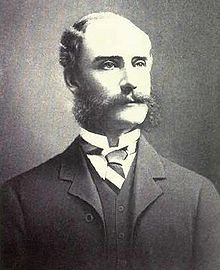

For the next several years Tomo settled down to his customary duties as guide and interpreter. When HBCo. trader Adam Horne became the first European to hike across the Island in 1856, Tomo was his right hand man. The following year, he assisted J.D. Pemberton, the colony’s Surveyor-General, explore from Cowichan Bay to Nitinat then return by boat via the Alberni Inlet.

Colonial Surveyor-General Joseph D. Pemberton. —Wikipedia

As early as 1851, Tomo had married and made his home in the Cowichan Valley, first residing at Somena, the Cowichans’ main village on the river at the future site of Duncan. Then, given a land grant by the HBCo., he and his wife settled beside today’s Garnett Creek at Cherry Point, Cobble Hill.

In 1855 Tomo Antoine aka Tomo Ouamtany, Thomas Williams, etc., etc., became the unwilling catalyst of another drama—this one resulting in what has come to be known as Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree.’

(To be continued)