Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree’ (Part 3)

As we’ve seen, throughout the 1850’s the Iroquois guide and interpreter Tomo Antoine was in the thick of almost every major exploration and police action that occurred on Vancouver Island.

He was, in fact, Chief Factor/Governor James Douglas’s right-hand man in the field.

For all that, he’s been all but forgotten.

Qumutsun Village, 1912—Wikipedia (Edward Curtis

* * * * *

As early as 1851, Tomo had married and made his home in the Cowichan Valley, first residing at Somena, the Cowichans’ main village on the river at the future site of Duncan. Reputedly given a land grant by the HBCo. in return for services rendered, he and his wife then settled at Cherry Point, Cobble Hill.

In 1855 Tomo Antoine aka Tomo Ouamtany, etc., etc., became the unwilling catalyst of another drama—this one resulting in what has come to be known as Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree.’

What follows is the long accepted account of this ancient drama; more recent research has suggested that the Tomo Antoine story, like everything else in this world, has twists and turns.

But, first things first—the saga of the ‘Hanging Tree’ as many historians have told and retold it over the past 168 years.

* * * * *

On Aug. 21, 1855, Tathlasut, said to be the young son of a Somena chief, shot the HBCo. scout from ambush in retaliation for Tomo’s seduction or attempted seduction of his intended bride. The musket ball passed through Tomo’s left arm and lodged in his chest and was at first thought to be fatal.

Upon being rushed to Victoria for further medical treatment, his arm had to be amputated. But, maimed, bitter and, some have suggested, now estranged from the Cowichans with whom he’d long been on good terms, he lived.

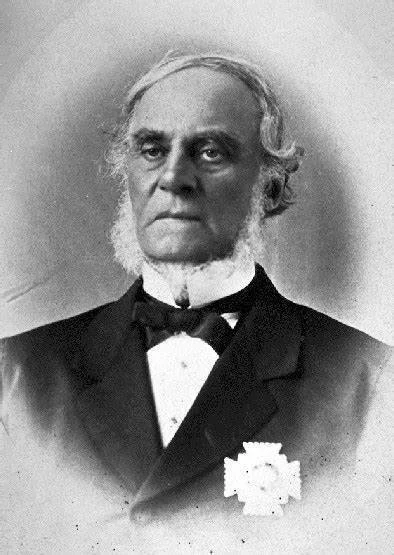

Vancouver Island colonial governor and “statesman” Sir James Douglas. —www.biographi.ca

Gov. Douglas responded with characteristic determination. Motivated more by a concern to enforce the peace among the tribes than by personal loyalty to his longtime servant, he ordered another ‘expeditionary force’ to the Cowichan Valley.

Ironically, this appears to have presented him with a delicate administrative problem—how to justify the expense and necessity of such an action with his superiors in London.

Keeping the peace was one thing. But to respond with a force three times greater than had been used previously, in response to the attempted murder of a half-caste, wasn’t on the same plane as asserting colonial authority by avenging the slaying of shepherd and HBCo. employee Peter Brown.

Hence, so some historians believe, Douglas’s deliberate references to Tomo Antoine in correspondence and reports as “Thomas Williams, a British subject”.

As had been the rationale in the shooting of Peter Brown, that he’d “insulted” (propositioned?) his guests’ wives, the Cowichans considered Tathlasut’s attack on Tomo to be justified because of his attempted or successful seduction of his betrothed. Perhaps, too, they took Tomo’s behaviour to be a betrayal of the trust and respect they’d accorded him up to this time.

University of Victoria law professor Hamar Foster, who “specializes in colonial legal...and Aboriginal history,” has posited that there was another dynamic at play.

Tomo had recently served as guide to the HBCo.’s J.W. McKay who’d led the first European exploration of the Cowichan River. McKay’s report to Douglas included favourable references to the Valley’s agricultural potential—meaning its desirability for settlement by colonists.

This land, obviously, had long been occupied by the Cowichan tribes.

As for the attempt made upon Tomo’s life, wrote Foster, “the Cowichans may not have regarded him as someone who automatically came under the protection of English law, and so resisted what they saw as an intrusion of British justice and military force into a lawful, perhaps even a privileged act of vengeance against a wrongdoer from another nation.”

Douglas’s first, perhaps ingenuous, dispatch to Henry Labouchere, Secretary of State for the Colonies, sets the stage for the tragedy we now remember as Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree.’

Secretary of State for the Colonies Henry Labourchere. —Wikipedia

“Thomas Williams, a British subject, settled in the Cowegin [Cowichan] country, was brought here this morning in, it is feared, a fatally wounded state, having been shot through the arm and chest, by ‘Tathlasut’ an Indian of the Saumina [Somenos] Tribe who inhabit the upper Cowegin District.

“Thomas is one of that class of men known in this country as ‘squatters,’ that is persons who have not purchased and therefore have no legal claim to the land they occupy, and though I have always made it a rule to discountenance the irregular settlement of the country, yet it is essential for the security of all, that those persons should be protected.

“I propose in the first place to demand the surrender of ‘Tahtlasut’ from the Chiefs of his Tribe, and should we not succeed in securing him by that means, the only alternative left, will be to march a force into he country for that purpose. The [Royal Navy] squadron now being here, a sufficient force can with the co-operation of Admiral Bruce be raised without difficulty and I feel assured that he will render every assistance in his power.

“I have only further to assure you that I will do every thing in my power to avoid collisions with the natives, and not push the matter further than is necessary to secure the peace of the country.”

The official account of what followed is that filed by Gov. Douglas with London and it’s his narrative of events that historians have to work with. It’s noteworthy that, for obvious reasons, this naval police expedition didn’t employ the services of Tomo Antoine.

“The troops marched some distance into the Cowegin valley, through thick bush and almost impenetrable forest. Knowing that a mere physical force demonstration would never accomplish the apprehension of the culprit, I offered friendship and protection to all the natives except the culprit, and such as aided him or were found opposing the ends of justice.

“That announcement had the desired effect of securing the neutrality of the greater part of the Tribe who were present, and after we had taken possession of three of their largest villages the surrender of the culprit followed.

“The expeditionary force was composed of about 400 of Her Majesty’s seamen and marines under Commander Mathew Connolly and 18 Victoria Voltigeurs [militiamen], commanded by M. M’Donald of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service.

“My own personal staff consisted of M’ Joseph M’Kay and M’ Richard Golledge, also of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service, and those active and zealous officers were always near me, in every danger.

”In marching through the thickets of the Cowegin Valley the Victoria Voltigeurs were, with my own personal staff, thrown well in advance of the seamen and marines, formed in single file, to scour the woods, and guard against surprise, as I could not fail to bear in mind the repeated disasters, which, last winter, befel [sic] the American Army, while marching through the jungle against an enemy much inferior in point of numbers and spirit [sic], to the Tribes we had en encounter.

“I also remark for the information of Her Majesty’s Government that not a single casualty befel the expeditionary force during its brief campaign, nor was a single Indian, the criminal excepted, personally injured, while their property was carefully respected....”

(It’s revealing that Douglas made a point of stating that the Cowichans’ property was “carefully respected” while also informing London that his force had taken possession of three of their largest villages, likely those of Clemclemluts, Quamichan and Somena. Revealing because, in subsequent police expeditions, holding villages with their food supplies and vital canoes for ransom against a fugitive’s surrender became standard procedure. In this case, it simply didn’t prove necessary.)

Douglas had timed his police expedition well. Aware that the Cowichans could muster as many as 1400 warriors, he’d landed his force when “1000 of these were engaged upon an expedition to Fraser’s River”.

Consequently, the Whites and the Cowichans were more or less equally matched in numbers but certainly not in firepower, and “no attempt was made, except a feeble effort, by some of his personal friends, to rescue the prisoner or to resist the operation of the law”.

So Douglas wrote in an early dispatch. He certainly conceded otherwise in a subsequent report to London when he seems to have felt compelled to bolster his case: “Our demands for the surrender of the criminal was answered by a rush to arms, and a tumultuous assemblage of the Tribe in warlike array.

“From thence arose the necessity of employing an armed force to support the requisitions of the Law, and the dangers to be guarded against, in our efforts to apprehend the criminal was a collision with the whole Tribe. To avert that calamity, if possible [I had to] impress on the minds of the Natives, that the terrors of the law would be let loose on the guilty only, and not on the Tribe at large, provided they took no part in resisting the Queen’s authority nor in protecting the criminal from justice...”

What followed was British justice as administered by the colonial authorities.

As in the case of the two Indigenous men accused of murdering the shepherd Brown who were tried by naval officers on board the HBCo. steamship Beaver, then hanged on Protection Island, Tathlasut was tried before a court convened on the spot.

His jury consisted of six naval officers and six petty officers who gave the charge of attempted murder, to quote noted history professor and author Barry Gough, “a full and patient investigation of the known and substantiated details of the case”.

It was Gov. Douglas who passed sentence of death, to be carried out that evening.

The gallows was a “majestic” oak tree, deliberately and symbolically chosen as being on or very near where Tathlasut fired at Tomo Antoine. (Cowichan lore places this tree near the intersection of today’s Jaynes and Tzouhalem roads.—Ed.)

It’s to be noted that he was convicted not of murder, but of “maiming Thomas Williams [sic] with intent to murder”. Douglas cited “Statute 1st Victoria chapt. 83 section 2 [which] considers felony, and provides that the offender should suffer death”.

The death penalty in the United Kingdom had been reduced to 60 crimes punishable by death in 1837, just 18 years before. Previously, it was a capital offence for shoplifting; sheep, cattle and horse stealing; sacrilege; mail theft; returning from transportation (imprisonment Down Under) without pardon; forgery; arson; burglary of a dwelling house and rape.

Capital punishment for attempted murder remained on the books until 1861—six years after Tathlasut’s execution.

All said and done, the real point of the exercise was to impress upon British Columbia tribes that committing murder (even a failed attempt to commit murder) would make them subject to, in Douglas’s words, “the terrors of the law”. Tathlasut’s hanging was “carried into effect...in the presence of his Tribe, upon whose minds the solemnity of the proceedings, and the execution of the criminal was calculated to make a deep impression.”

Apparently Douglas’s superiors in London weren’t entirely satisfied with his actions. (Readers are reminded that it took months for a dispatch from Victoria to reach London, be processed then replied to via sailing ship.) Douglas, who was always sensitive to criticism, defended himself thus:

“...I trust I may be permitted to make a few explanatory observations, in reference to the remarks in your Dispatch on the subject of the expedition to Cowegin, with the view of more clearly showing than was done in my report of the expedition, that the measure of sending an armed Force against the Cowegin Indians was only resorted to, on the failure of all other means of bringing the criminal to justice.

“Never was a [single] example more urgently demanded for the maintenance of our prestige [author’s italics] with the Indian Tribes than on that occasion...

“The natives of the Colony were also becoming insolent and restive, and there exist the clearest proofs derived from the confession of [Tathlasut’s] own friends, to show that the Native who shot Williams, felt assured of escaping with impunity. He, in fact told his friends that they had nothing to fear from...the whites, as they would not venture to attack a powerful tribe, occupying a country strong in natural defences, and so distant from the coast.”

In personally leading the expedition, he’d “adopted every other precaution, dictated by experience, to avert disaster and ensure success”.

He wasn’t, he insisted, motivated by “the love of military display...but solely by a profound sense of public duty, and a conviction founded on experience, that it is only by resorting to prompt and decisive measures of punishment, in all cases of aggression, that life and property can be protected and the native Tribes of this Colony kept in a proper state of subordination.”

After noting that the expedition tarried for two days after the execution so as to “re-establish friendly relations with the Cowegin Tribe, and we succeeded in that object, to my entire satisfaction,” he couldn’t resist commenting on the Cowichan Valley’s “beauty and fertility” and he promised to address its agricultural potential in further dispatches.

The bottom line for Douglas: “I have further much satisfaction in reporting that the result of the expedition has produced a most salutary effect on the minds of the Natives.”

So the governor wrote to his superiors in London. Surely, to no one’s great surprise, the Cowichans were, Douglas’s claims to the contrary, less than happy with the Whites’ concept of justice. RN Capt. Macdonald later alluded to their true state of mind with his observation that he’d seen “many indications that their approval was withheld and that they yielded only to force”.

In due course the Colonial Office, with only Douglas for its source of information, rubber-stamped his actions with a single caveat, an unidentified official writing:

“...In the present instance I have no hesitation in approving your proceedings, which the peculiar and aggravated circumstances of the case appear to have been justified, but I would remind you that the extreme measure of sending an Armed Force against the Indian Tribes must be resorted to with great caution, and only in a case which urgently demands the adoption of such a measure...” (My italics—TWP.)

* * * * *

At the beginning of this series on Cowichan’s ‘Hanging Tree’ I invited Chronicles readers to judge for themselves the fairness of British justice as it was practised in B.C.’s formative colonial years. Even accepting that the accused murderers in each case described were guilty, could naval officers serve as their jury of “peers”?

Who spoke on their behalf as defence counsel? Did their motivations and actions based upon tribal traditions not count as mitigating factors? Did they have even the faintest chance of acquittal?

To try, convict and hang on the spot, as occurred in this case, certainly seems to suggest more of Judge Lynch than British law as it was practised in the Old Country and as it more or less continues to be practised today.

BUT: How else to keep the peace when British Columbia’s armed and warlike First Nations vastly outnumbered European arrivals?

* * * * *

Professor Hamar Foster: “...It is clear not only that the Cowichans submitted because of Douglas’ superior force, but also that some of them bitterly resented his actions and continued to feel aggrieved long afterwards...”

“...Death was an extreme penalty for such an offence [attempted murder], whether or not the Cowichans accepted that Tathlasut was guilty of attempted murder rather than lawful retaliation.

“Moreover, it was extreme even in English law...by the mid-1850s the practice in England was not to carry out the death sentence ‘unless life had actually been taken’.” (He’s citing British Columbia’s Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie in an 1869 case.)

Foster: “The [Cowichan] execution was an emphatic statement about how the government would protect those it chose to define as settlers, whatever the reason for an attack upon them...Sending over [400] men to arrest Tathlasut for wounding Tomo Quamtomy was therefore a new kind of excess.”

(Source: The Queen’s Law Is Better Than Yours: International Homicide in Early British Columbia, published in Essays in the History of Canadian Law: Crime and Criminal Justice, University of Toronto Press, 1994.)

As for the objectivity of a jury of British officers, what are we to think?

We have only Gov. Douglas’s bare-bones account of the trial—no transcript, no record whatever of what was said for and against the accused, whether Tathlasut spoke in his own defence—nothing.

(As opposed to Douglas’s defence of his own actions to his superiors.) And, since it’s evident that Tathlasut believed that he’d acted as most of his tribesmen would have acted under the circumstances, it seems hardly likely that he’d have attempted to refute the charge.

Referring to the trial of the two men charged with murdering HBCo. shepherd Peter Brown, Professor Foster notes, however, that thet did plead not guilty—as, indeed, they weren’t guilty under the laws of their own people.

But the British newcomers with all their might were now in command; there was no turning back the clock. And British justice, however we might view it with wisdom gained from more than a century of hindsight, was now the law of the land.

Even if there had to be further, and bloodier, police expeditions to come.

* * * * *

We’ve by no means finished the story of Tomo Antoine whose anger and bitterness after he recovered from the loss of his arm would again lead him to violence and—this time—to his own trial for murder.

In truth, there’s more to the story of Cowichan’s “Hanging Tree.’ But, after three weeks, it’s time for a change of pace and we’ll come back to Tomo Antoine and the ‘Hanging Tree’ another day.