Deserter Islands Murders Cost Governor His Job

Feuding Governors: The Grand Inquisitor versus the Monopolist.

Recent notice of this talk by acclaimed historian Barry Gough as one of the Marion Cumming Lecture Series hosted by the Oak Bay Heritage Foundation, reminded me yet another great story within a great story.

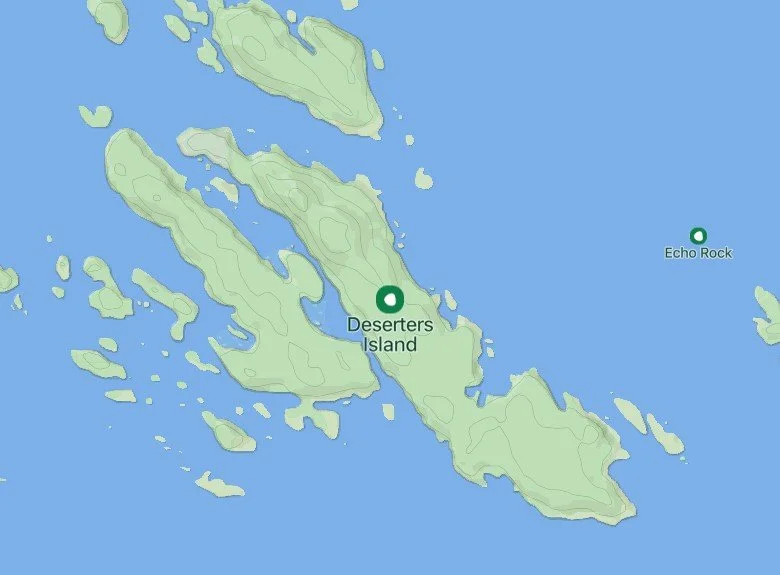

In this case, how the northern Deserter Islands near Port Hardy got their name.

Who did Gough mean by the Grand Inquisitor and the Monopolist? The reference to feuding governors gave it away for me: Richard Blanshard and James Douglas, the first and second governors of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island.

Ill-starred Richard Blanshard’s governorship of Vancouver Island was doomed from the start. —B.C. Archives

The story within the story is that of the tragedy that precipitated Blanshard’s resignation after just eight months on the job, and the role played by the remote Deserter Islands.

* * * * *

Today, it’s scarcely remembered, even by historians: a case of murder with political repercussions that resounded halfway around the world from then hardly heard-of Vancouver Island to the highest offices in the British Empire.

Although the legend which has drifted down over the past century and three-quarters has been embellished, there has never been any need to fancify the record. It’s one more of those cases where truth really is more amazing than fiction.

So let’s begin...

Our story can be said to have begun in 1836 when Hudson's Bay Company physician Dr. W.F. Tolmie, then stationed at Fort McLoughlin, Bella Bella, learned of coal outcroppings on the northeastern tip of Vancouver Island. A survey confirmed the report but it wasn’t until 1846 that the British Admiralty expressed interest in the deposits.

More years passed before the HBC decided that Fort McLoughlin, which had been abandoned, should be replaced in some form.

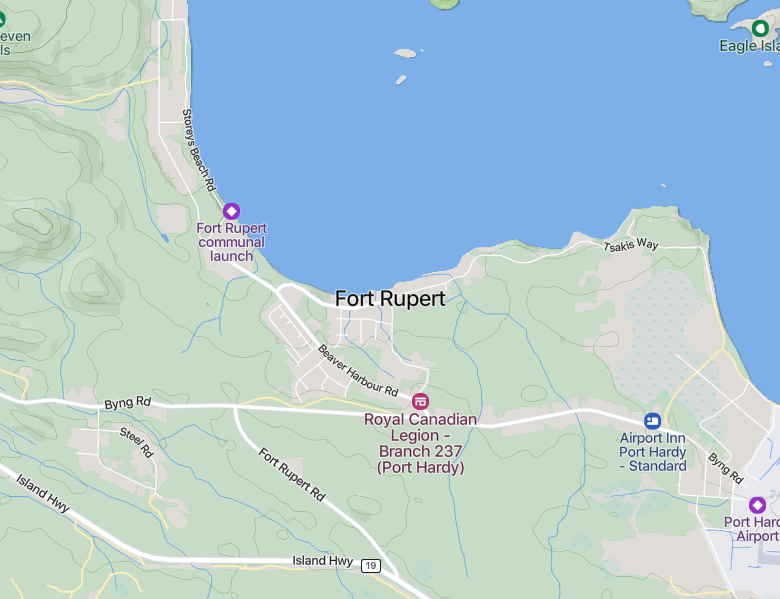

Encouraged by the Admiralty’s renewed interest in potential Island coal, the company embarked upon construction of a new ‘super fortress’ in 1849. to be christened Fort Rupert. Capt. W.H. McNeill was ordered northward aboard the venerable company steamer Beaver with men and supplies to build what was intended to be one of the strongest fortifications west of the Rockies.

This, because of the neighbouring Nahwitti tribe’s reputation as being among the fiercest on the west coast.

The Fort Rupert shoreline as it appeared during a visit by the renowned geologist George M. Dawson. —Wikipedia

With Rupert's completion, the formerly silent shores of Beaver Harbour were said to resound with “shrieks and cries, the noise of fighting and the unearthly yelling and rattling of medicine men [which] made the nights terrifying to the whites and enclosed within the picketed walls...” A village sprang up alongside the fort upon the arrival of 100s of tribesmen of the Kwakiutl Nation.

Coincidentally, as the founding of Rupert progressed, a far more significant event had occurred 1000s of miles distant, in the British Colonial Office: the appointment of “an almost unknown and completely inexperienced” 32-year-old barrister named Richard Blanchard as first governor of the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island.

As one historian has wryly noted, Blanchard's “was an unhappy lot during the year and a half that he remained in the colony.

“He received no salary and no allowance for expenses; cost of living was high, and independent settlers were few. The majority of the white inhabitants of the island were employed by the Company, and looked to the officials of the organization for instructions. The result was that the unfortunate Governor had little to do, except [to spend] his time in hating the Company, which he blamed for all his roles.”

This quick assessment is, perhaps, unjustly harsh. Whatever the case, Blanchard's tenure in the new colony was to be short and bitter, involving one dispute after another with the HBC's iron Chief Factor James Douglas. The Fort Rupert tragedy was to be the issue upon which Blanshard would give his resignation within just eight months of his landing in Victoria.

Hudson’s Bay Co. Chief Factor James Douglas was the real governor, in fact if not in name. —Wikipedia

After several skirmishes with Douglas, the governor chose to oppose him head-on over the labour problems besetting Fort Rupert, where professional miners imported from the Old Country were rebelling against work conditions and food. Accordingly, Blanshard appointed young medic Dr. J.S. Helmcken to the post of magistrate at Rupert.

But Helmcken found his hands to be tied when it became apparent that the miners didn’t really wish to achieve their demands but to secure their release from their contracts with the HBC. This desire became all the stronger when word of California's gold discoveries reached the North Country. It was during this tension that the bark England arrived in Victoria.

Upon unloading her cargo, her orders were to sail to Rupert to take on coal for California—the golden opportunity for three crewman of another Company vessel, the Norman Morrison, to desert and stow away aboard the England for a free ride to El Dorado.

With the England’s arrival, the disgruntled miners immediately learned of the stowaways and several of the more daring plotted to join them aboard the bark for the voyage southward. Their scheme collapsed suddenly when the Beaver arrived, the stowaways leaping to the conclusion that she'd come for them. Panic-stricken, wrote early historian B.A. Mckelvie, “they left their hiding place and took refuge in the woods.

“The Beaver, however, did not stay long. When she was gone, Dr. Helmcken told Capt. Brown to get word to the sailors to return to the ship, as it was unsafe for them to remain in the forest where they were isolated and might be attacked... The friendly warning the men believed to be given for the purpose of trapping them...”

—Mapcarta

Here’s where the bloody legend that today is accredited with the christening of the Deserter Islands really begins, if not altogether accurately.

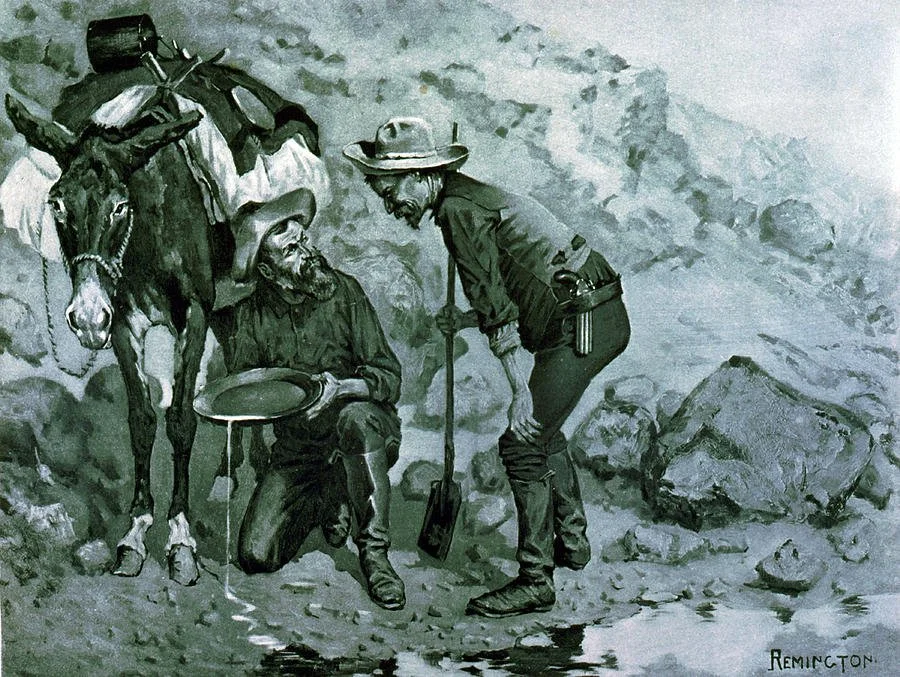

Briefly: About 1858, a ship put in to load Rupert coal. But as she lay at anchor the electrifying word “Gold!” electrified her crew with the news of a great strike in the Cariboo. (1858 was the beginning of the Fraser River gold rush; the Cariboo’s came later.—Ed.) The ship's master, understandably, received the news with misgivings. Familiar with the San Francisco Bay death fleets after 1000s of seamen had abandoned their square-riggers during the rush of ‘49, and faced with the threat of having to sail undermanned if members of his crew deserted, the captain placed his crew under guard.

“Gold!” was the cry from California and the rush was on.—pixels.com

Despite his precautions, eight men stole a longboat that night, filled it with supplies pilfered from the ship’s stores and slipped away into the darkness. Intending to hike overland to the goldfields, they set course for Seymour Inlet, to the northeast. Then, six miles from the ship, and confident there would be no pursuit, they camped on a small island.

With dawn, and word of their flight, the captain was beside himself with rage, exhausting his vast store of profanity on his careless mate before vowing to have the culprits returned rather than sail short-handed. He contacted the local tribal chieftain who readily offered to provide his best men for the job. After some haggling, they came to terms, the captain agreeing to pay so much “per head”.

And with that unfortunate turn of phrase—so the legend goes—the deserters’ fate was sealed.

Leaping into their canoes, the warriors soon overtook their quarry and fulfilled what they thought to be their part of the bargain—as their chief reminded the horrified ship master later when collecting the bounty: he’d offered to pay a flat rate per head. Because that's exactly what he got—eight heads, neatly stacked on his deck.

Which concludes the popular if enhanced version of how the Deserter Islands were named. Surprisingly, the official account is fascinating enough without any help from fertile imaginations:

Having ignored Helmcken's warning, the deserters, Fred Watkins and brothers George and Charles Wishart, had continued their flight. Days later, they encountered three Nahwitti braves near Shushartie. The latter were friendly that day—so they claimed after—and approached the Whites to warn them of an impending raid by the fierce Haida.

But the panic-stricken deserters waved an axe, threw rocks and cursed, trying to scare them off.

Infuriated by this unwarranted rebuke, the Nahwittis attacked and within minutes had run the deserters to earth and hacked them to pieces. The mutilated bodies of the Wisharts were buried under some brush, that of Watkins weighted and dumped into the sea.

When word of the murders spread, it had two opposite effects: terrifying the miners of Fort Rupert and emboldening the Nahwittis into the open belligerence. Anaccountably, the frightened miners chose to abandon their fortress for Shushartie, leaving but a handful of company officers to face the crisis. The emergency worsened with each passing hour, the tribesmen becoming ever bolder, some even climbing the palisades to “leer down at the unhappy whites, who realized that any demonstration would be signal for an attack”.

They were saved by the timely arrival of another HBC vessel, the Mary Deare.

At this dramatic change in fortune, the miners returned to the fort as HMS Daedalus also arrived with Governor Blanshard to restore order. After consultation with Blanshard and Capt. G.W. Wellesley, Helmcken volunteered to meet with Chief Nancy to demand the murderers’ surrender.

Accordingly, in the company of an equally brave interpreter named Battineau, Helmcken proceeded to the Nahwitti village to meet with Chief Nancy. Although historians haven’t given him due credit, it was undoubtedly to the old chief’s credit as much as it was to Helmcken’s and Battineau’s courage, that they weren’t harmed.

Nancy held his warriors, several hundred strong and armed, in check while admitting to Helmcken during their all-night parley that his men had killed the deserters. He offered reparations which the magistrate couldn't accept, reiterating his demand that the guilty men be surrendered for trial.

The meeting ended in stalemate, Chief Nancy refusing to hand over the murderers, and Helmcken and Battineau returned to the Daedalus to report. Faced with no apparent alternative, Blanshard deferred to Capt. Wellesley, who prepared his men for landing.

Curiously, as historian McKelvie pointed out, the expedition chose to land at dusk and, faced with darkness, camped on the beach overnight. As a result, when Lieut. Burton's bluejackets and marines stormed the Nahwitti encampment at dawn, they found it to be abandoned. Burton then followed his orders, reducing the village and all canoes to ashes.

The farce wasn’t ended for, critically sort of supplies, Capt. Wellesley announced that the Daedalus had to depart for San Francisco and cavalierly dumped Governor Blanshard at the fort, to make his own way to Victoria.

And with that, Wellesley sailed northward, intending to round the Island for the open Pacific. But not before a final skirmish ended ignominiously with an officer and two seamen being wounded in a brief exchange of cannon and musket fire until the hungry man-of-war was forced to disengage and continue on to California.

On Nov. 18, 1850, a month after the Fort Rupert debacle, Blanshard submitted his resignation to the Colonial Office. Stung by what amounted to little more than a “paper” post, he continued to perform his duties as he saw them until his resignation was accepted, when he left the colony forever. It was an ignominious ending to his attempt to fill an impossible office.

But it wasn't to be the end of the tragedy at Rupert.

The final, bloody scene was enacted the following summer when HMS Daphne, Capt. Fanshawe commanding, brought White man's justice to northern Vancouver Island with a vengeance.

Fort Rupert is peaceful in this watercolour by Capt. Edward Gennys Fanshawe. This same naval officer ordered the total destruction of the Nahwitti village. —Wikipedia

With the loss of their first village, the Nahwhittis had invested great effort and ingenuity in building a formidable fortress on an island in Bull Harbour. Chief Factor James Douglas touched upon the “battle” in a letter in August, saying that the tribe “have been rather severely handled by a boat party of 60 men and officers [under Lieut. Lacy] from the Daphne, who surprised their village and carried it by assault, in the midst of a severe fire from the natives—with very trifling loss, say two men slightly wounded, who have since recovered.”

Douglas described the camp as having been “very strong, and protected with stockades, which they thought impregnable, and were consequently rather surprised when they saw it carried by a body of white faces...”

When the bluejackets swarmed over the walls, they again found the occupants had slipped away, leaving only their dead—including old Chief Nancy—and wounded. As before, the navy fired all homes, canoes and food stores. Concluded Douglas, “They have sustained a very severe loss. The tribe is now completely dispersed and are reported to be somewhere on the west side of the island.”

Still, Her Majesty's law wasn’t satisfied. The murderers of the three deserters were still at large and Blanshard, who’d accompanied the Daphne on the raid, posted a reward for their arrest. As it turned out, the Nahwittis had had enough and, dispersed and disheartened, ordered the wanted man to surrender themselves. When they naturally objected to this, two were slain, the third making his escape.

To make up the necessary number, a slave was killed and the bodies taken to Fort Rupert.

Concluded Douglas in another letter: “The mangled remains of the criminals were taken to Fort Rupert, and after being identified by the chiefs of the Quakiolth [Kwagu’l] Tribe, were interred near the Fort, so that there is no doubt as to their having met the fate they so justly deserved.”

Her Majesty's Navy would call at the northern outpost again in future yearsto answer native recalcitrance with cannon fire, but, officially, the case of the Fort Rupert murders, and the naming of the Deserter Islands, was closed.

At least one however, didn't forget: Governor Richard Blanshard. Having already submitted his resignation, embittered by the ineffectual role to which he’d been assigned, and possibly saddened by his part in the Rupert incident, he complained of Helmcken’s competency. Although he’d appointed the doctor himself, Blanshard regretted his choice in dispatches to the Colonial Office, saying that Helmcken hadn't fulfilled the office with impartiality, having instead acted at all times in the interests of his employer, the Hudson's Bay Company.

This state of affairs, Blanshard charged, in effect made an HBC employee “judge in his own case... as most of the legal problems which arose were those between the company and the Indians”.

On that questionable note, the Fort Rupert tragedy became history.

* * * * *

It may help readers to know that The Deserters Group, a small group of islands that includes one named Wishart for the slain brothers, is in the Queen Charlotte Strait region of the Central Coast of British Columbia, off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island to the north of Port Hardy. There’s also Wishart Peninsula.

Since 2006, this series of forested islands, bare rocky islets and “wave-wracked reefs” which offer protection to small boaters navigating the Inside Passage from Vancouver Island, have been part of the Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna/Deserters-Walker Conservancy.