Did Notorious Civil War Guerrilla Leader Escape to Vancouver Island? (Conclusion)

(Conclusion)

Was John Sharp really who he claimed to be—who many, in fact, also believed him to be—the infamous Confederate guerrilla leader, William Clarke Quantrill?

Capt. William C. Quantrill is ranked as one of the most notorious participant in the American Civil War. —Wikipedia

If he was an imposter, then who was he? No John Sharp appears in the existing records.

Whoever he was, the popular account of his death is as violent as that of Quantrill who's officially recorded as having died from wounds in a military hospital in Kentucky in June 1865. After the newspaper stories appeared in August 1907, stating that Quantrill, as John Sharp, was alive and well at remote Coal Harbour, he died as the result of a brutal beating.

So began the greatest myth of John Sharp/William Quantrill: a tale of a 40-year-long grudge and murder of vengeance.

According to this legend, two Americans who’d suffered at the hands of Quantrill during the war, upon seeing newspapers claiming “Quantrill lives....!" journeyed northward on a mission of revenge. Said to be “obviously Southerners,” they found Sharp at his isolated cabin and killed him.

It was about the time that they were fleeing southward, wrote respected B.C. historian Bruce A. McKelvie in his book, Magic, Murder and Mystery, that the late Guy Ilstad found Sharp in his cabin, alive but severely injured.

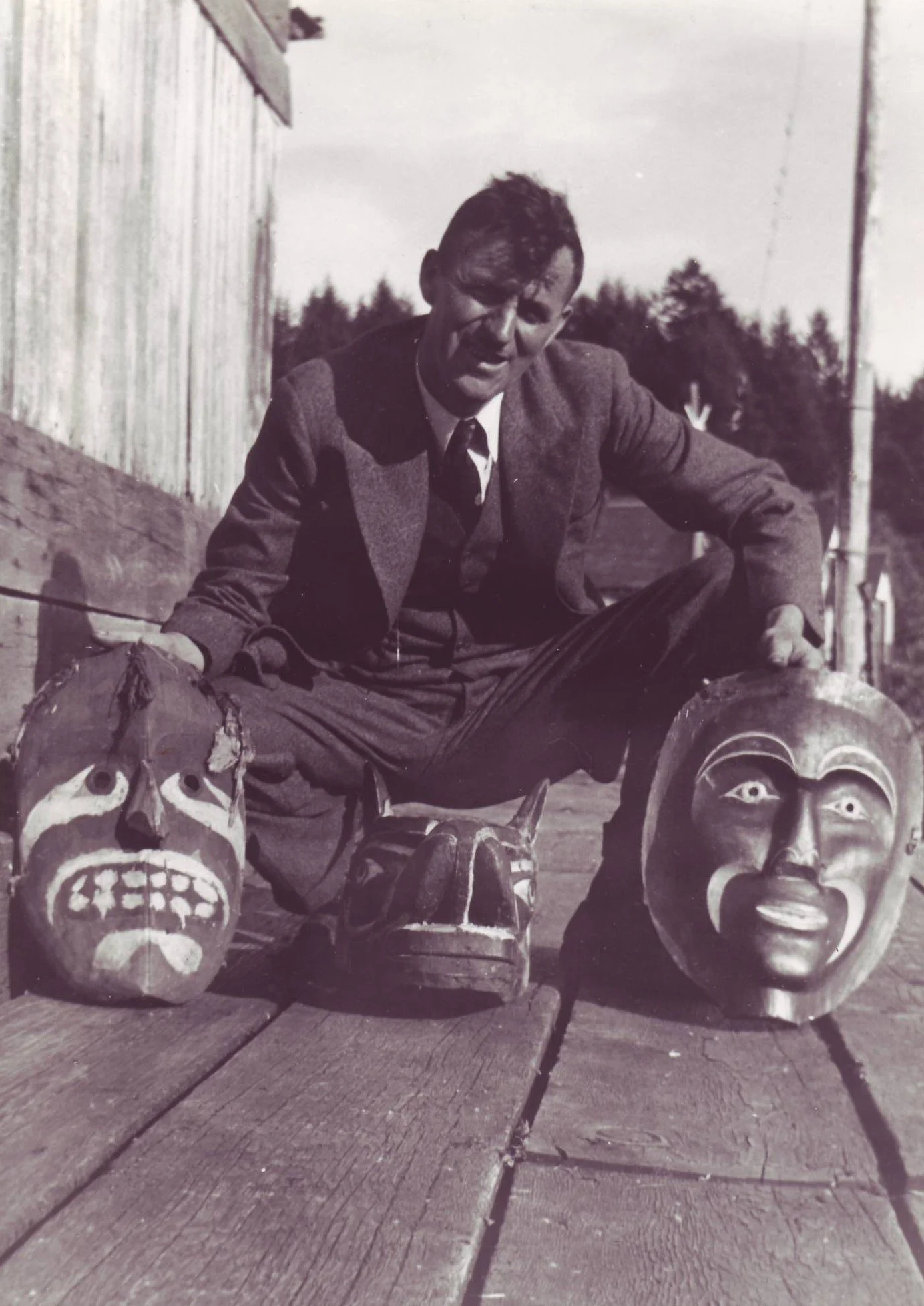

The late Guy Ilstad posing with three examples of Indigenous art. —Courtesy Guy Ilstad

Last week, I introduced you to Mr. Ilstad as having been a boy who lived nearby and who’d become one of Sharp’s few friends in isolated the Holberg Inlet, Quatsino area. Years after he’d been interviewed by Mr. McKelvie, I, too, sought him, out by mail, as he still lived in Quatsino and I lived in Victoria. Over several years of correspondence we became almost friends.

Then at the start of my writing career, I wasn’t much older than he was when he knew John Sharp.

Picking up from last week, back to Mr. McKelvie: “Following the publication of the story in The Colonist, Seattle newspapers reprinted it. This brought to light several residents of the American city who had met ‘the mystery man of Quatsino.’

“After the appearance of the news—or conjectures—based on the newspaper articles, it would be some weeks later, two men, obviously from the South, arrived at Victoria and registered at the Dominion Hotel. PHOTO They were anxious to go to Quatsino Sound. During the two days they stayed in the capital city, they kept to themselves.

“They boarded the steamer Tees on her sailing for the West Coast, and on shipboard made cautious inquiries about ‘an old man named Sharp.’ Arriving at the Sound, they immediately sought transportation from the docking place of the steamer, to Coal Harbour.

“When the Tees sailed on her southern Voyage the next day, the two strangers were again passengers. Arriving at Victoria, they took the next steamer to Seattle, and were not seen again. Provincial Police later—much later after they were informed of the death of John Sharp—tried to check up on these two men, but nothing could be found.

“It was a cold trail. It was just about the hour that the Tees was leaving Quatsino that young Ilstad approached Sharp’s cabin Coal Harbour. The door was ajar.

’I went inside,’ Mr. Ilstad recalled. "I heard a groan and looked towards the old man's bunk. After my eyes became accustomed to the dimness of the room, I saw Sharp was stretched on it. He was an awful sight. His face was covered with blood, and his white hair and whiskers were matted with it.

“I went to him, calling out, ‘What's happened?’ My voice must have aroused him for he recognized me. ‘Go and get me some whisky,’ he whispered.

‘Who hit you?’ I asked, for a heavy iron poker that he used for his fire was on the floor beside the bed. it was covered with blood.”

“The weapon was a three-quarter-inch iron poker about two feet long," Mr. Ilstad told me. "The marks on the poker were quite plain on his temples, there were grey hairs on the iron, and welts showing on Sharp's head.”

Ignoring Mr. Ilstad’s repeated, “Who hit you?” Sharp kept insisting that he fetch him some whisky. “I was unable to get liquor for him, but I knew that he was in need of help immediately, so I went off as fast as I could to get some assistance for him. I told several men, and they went to his house.”

They found Sharp to be still conscious but he was angered that they had no liquor for him. They, too, questioned him as to his injuries but, as with Mr. Ilstad, he refused to say who hit him and why. However, aware that he was dying, he asked that his beloved dog, Toby, be shot and buried with him, which was done.

When, hours later, he lapsed into unconscious and died, he took the identity of his killer or killers to the grave.

“There were not many at his funeral, " said Mr. Ilstad, “perhaps a dozen, nearly all from Quatsino. In 1939 the air force bulldozed the [grave] site. No trace can be found now.”

Concluded McKelvie: “Consensus of opinion about Quatsino at the time, and rated as a strong possibility by the authorities later, was that the publicity recently given to Sharp being Quantrill had caught the attention of some persons from Kansas or Missouri who had reason to hate Quantrill, and they had made the long trip to the North West Coast to revenge some incident of the Civil War, more than 40 years before.”

John Sharp, whether or not he was indeed William Quantrill, was indeed dead. But it was months before B.C. Provincial Police Constable Arthur Carter left Victoria to investigate what had become a mystery of grand proportions. As the story had travelled throughout the Pacific Northwest, with each telling the tale had become even more fanciful.

This cloud of exaggeration and honest error persists to this day despite Constable Carter’s belated investigation having led him to conclude that Sharp died of "chronic alcoholism.”

According to Mr. Ilstad, two Americans were suspected for a time; perhaps this is how the legend of revenge originated.

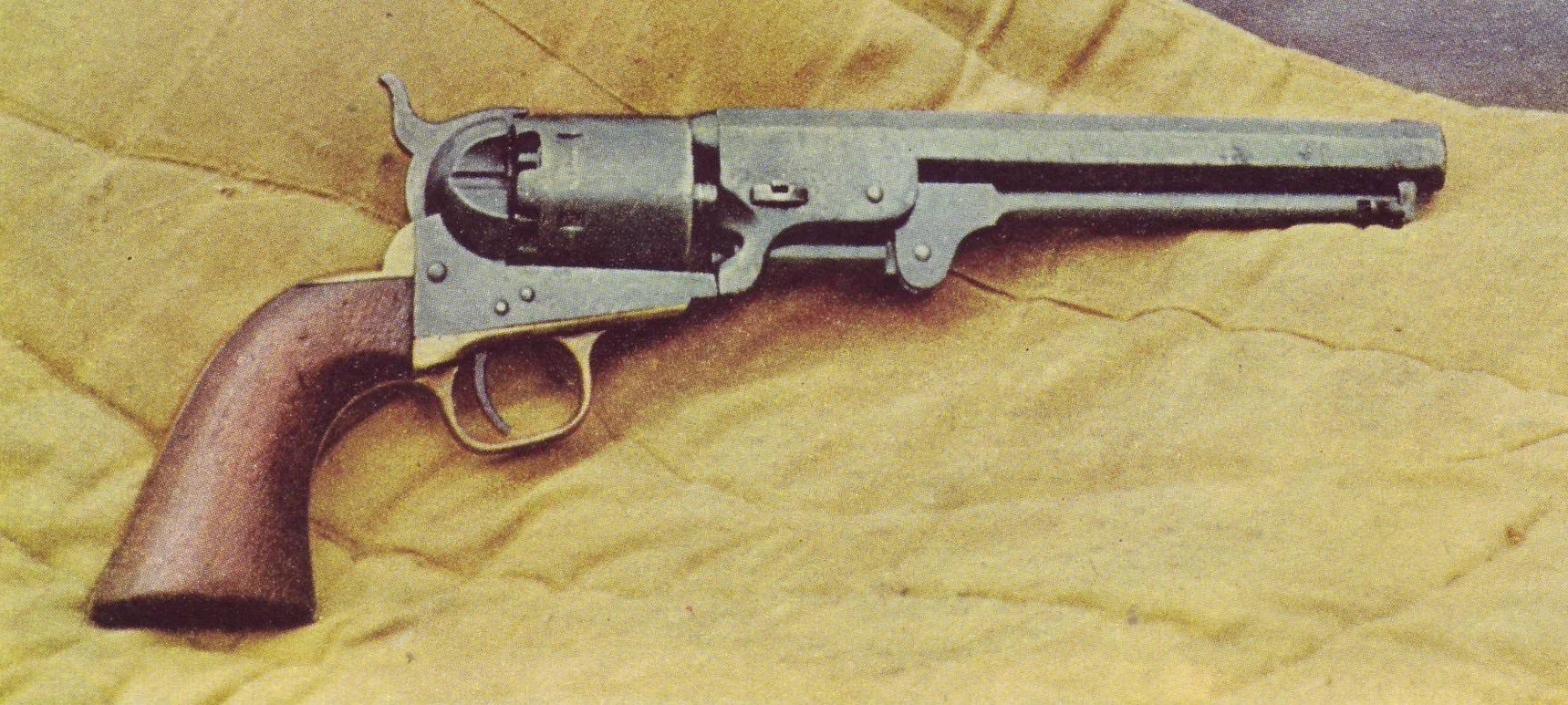

Searching Sharp’s few effects, Carter found two cap-and-ball Colt revolvers, the butts of which were engraved with the initials ‘W.C.Q.,’ which could have meant ‘William Clarke Quantrill’. Carter also found several letters addressed to Quantrill.

The pistols in John Sharp’s few effects would have been much like this Colt .44 Navy percussion. —True Men’s Magazine, 1960

Sadly, what became of these articles isn’t known today.

During a September 1965 visit to Victoria, 85-year-old George Nordstrom of Quatsino was interviewed by a Colonist reporter concerning his part in the remarkable Sharp legend. At that time, Nordstrom, who’d investigated Sharp’s death as justice of the peace, said, “I am convinced that John Sharp was actually Jesse James."

He based his belief on information given him by his late father who “knew of the gangs when they were operating in the Dakotas... "

When examining Sharp’s meagre possessions, he found “nothing there to show his identity or prove his background. All we found was a portrait which we assumed was a picture of his son. Years later, I saw a picture of a man called Dalton who who claimed to have been Jesse James. He looked like the portrait that we found, and I think he was the son of old John Sharp,” Nordstrom said.

Upon inspection of Sharp’s body he discovered "it was riddled with wounds—bullet holes, sabre and bullet wounds. Some of the wounds show where he had been pierced by a three-cornered bayonet."

Today, the mystery of John Sharp's true identity remains as deep as it was in 1907. If he wasn’t Quantrill, there can be little doubt that he was one of the guerrillas. He knew too much about their activities in Kansas and Missouri to have been anything else. And he did possess Quantrill's guns and letters. So who was he?

No John Sharp appears on any of the enrolment rosters in existence and most of the better known of Quantrill's men can be accounted for. Ed Terrell, the Yankee raider, was killed but weeks after capturing Quantrill. Was it just by chance that Sharp found himself in the final years of his life at isolated Coal Harbour or was he, at least originally, hiding out?

Some questions to ponder:

Why did he speak of his past only after his tongue had been loosened by whisky?

Is it coincidence that his description matched that of Quantrill and that he had a ‘Northern’ accent?

Was he just a pathetic old man who borrowed the reputation of a desperado for a few months precious limelight?

Why was he identified as Quantrill by Duffy, a respected businessman with no known reason to lie? Was Duffy simply mistaken?

Was Sharp given the guns and letters by a dying Quantrill in a Kentucky farm house?

Or: was Sharp one of Terrell’s men and he’d stripped the dying Quantrill of his weapons and personal effects?

So many other questions remain unanswered. As we’ve seen, Terrell’s men didn’t realize they’d wounded and captured Quantrill, who’d identified himself as a Capt. Clarke, at the Wakefield farmhouse. It had been two days before they realized their mistake and then moved the paralyzed officer to a military hospital where he died days later.

At least two sources state that Quantrill’s mother identified his partial remains by a chipped tooth and a missing finger.

Alas, like most questions concerning William Clark Quantrill, the "bloodiest man in American history,” these probably will never be answered. To quote American historian Wm. Elsey Connelley, “Of [Quantrill’s] death, burial and exhumation no man has been able to speak with confidence.”

In a comprehensive account of Quantrill’s fatal encounter with Terrell’s men in the March 1999 issue of America’s Civil War magazine, American historian Stuart W. Sanders told how the priest who’d converted him had him buried in an unmarked grave in the Louisville Catholic Cemetery.

As noted previously, in 1887, childhood friend William Scott obtained Mrs. Quantrill’s permission to exhume the remains for reburial in his Canal Dover, Ohio birthplace. But it’s known that Scott kept “the majority of the bones,” some of which he donated to the Kansas Historical Society. That society also acquired the rest of the remains upon Scott’s death and interred them in a local cemetery.

Which was just as well as, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, Scott’s son had used the skull in fraternity initiations! Ohio’s Dover Historical Society has a life-size wax replica of Quantrill’s head which can be viewed by request.

Today, after all that, Quantrill’s bones rest in three separate locations. The “dust” of his ribs and spine are in Louisville, Kentucky, an arm and the shinbones are buried in Higginsville, Missouri, and the rest (as of 1992) are buried in Dover, Ohio.

One of W. C Quantrill’s three grave headstones. Note the misspelling of his middle name; it’s missing the ‘e’. —www.findagrave.com

With the obliteration of John Sharp’s grave at Coal Harbour in 1939, there’s no way, now, of confirming by DNA if he was in fact William Clarke Quantrill.

Historian Sanders has defined Quantrill as a notorious killer who gave no quarter and expected none, who “cut a violent swath wherever he went. The sensitive young schoolteacher became one of the most dangerous and despicable figures of the Civil War.”

* * * * *

William Quantrill’s legacy continued to be one of violence, three of his younger followers, Jesse and Frank James, and Cole Younger went on to achieve legendary status as outlaws.

Today, more than a century later, we have Sharp Creek named for the “mystery man of Quatsino,” and, in the U.S., the William Clark Quantrill Society continues to “celebrate Quantrill's life and deeds”.