Did Notorious Civil War Guerrilla Leader Escape to Vancouver Island?

(Part 1)

Google William Clarke Quantrill and you’ll find reference after reference to a man who’s immortalized not as a hero or great Confederate general of the American Civil War but as what we term today, a war criminal, a mass murderer.

William C. Quantrill was, perhaps, the most notorious participant in the American Civil War. —Wikipedia

From school and Sunday school teacher to “the bloodiest man in American history” in a matter of just a few years, his was quite a career—one that ended violently at the age of 27 during a skirmish with Federal troops.

At least, that’s the accepted version of Quantrill’s death.

But there were those who strongly disagreed. Including two Americans who, the story goes, travelled all the way to Vancouver Island’s isolated Coal Harbour, where the fugitive guerrilla was living under cover as a watchman by the name of John Sharp.

Their mission: to settle old scores.

Or so that version goes.

The fascinating story of John Sharp alias William Quantrill is one that intrigued me at the start of my writing career. How fortunate I was to follow it up and make contact with the last living man who’d known Sharp on Vancouver Island.

He’d been just a boy at the time, a neighbour and friend of the old caretaker, and it was he who found Sharp in a pool of blood.

If ever I’ve had doubts as to my choice of career, it’s stories like the mystery of John Sharp that quickly put them to rest.

* * * * *

I was reminded of John Sharp aka William C. Quantrill, by an email from Jack Bates who hosts his own website, History of Work Point Barracks:

“Hello. I love historical articles of interest from Vancouver Island and am familiar with your many works... I would like to ask you if you have, or would be inclined to pursue the story of John Sharp, of Quatsino.

“He was alleged to have been William Clarke Quantrill of American Civil War fame, depending on how you look at it... This local story started in the Victoria Daily Colonist, August 9th 1907, page 3. Looking forward to hearing from you. Regards, Jack.”

So I dug into my files and here you are, Jack, and fellow Chronicles readers, Part 1:

* * * * *

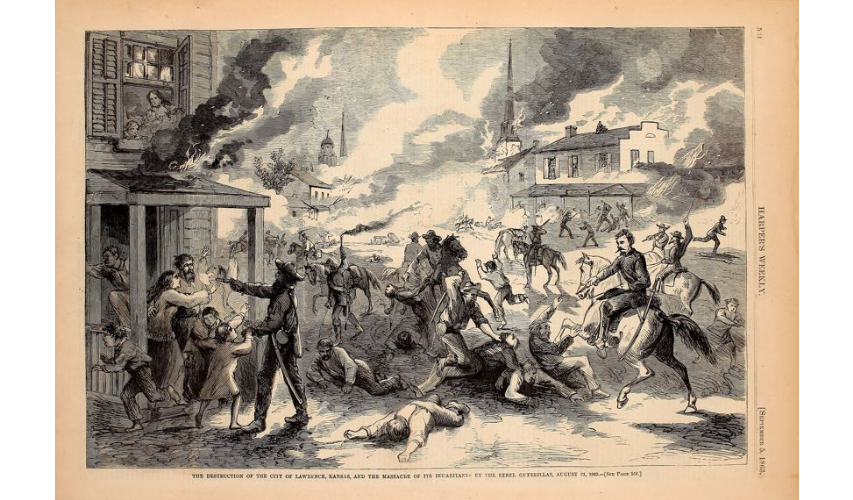

Artist’s conception of the infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas. —Kansas City Library

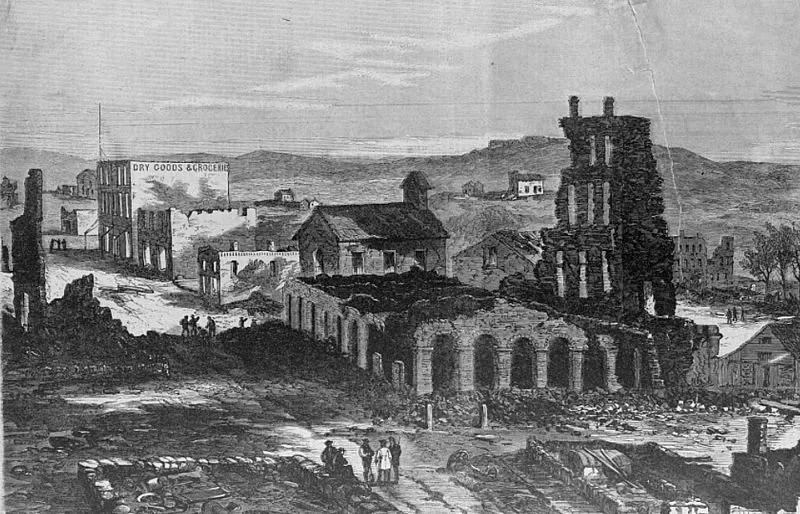

What was left of much of Lawrence by Quantrill’s raiders, Aug. 21, 1863. An estimated 150 men and boys were killed, mostly execution-style, in what’s referred to in history books as the ‘Lawrence Massacre.’. —Wikipedia

For readers who are unfamiliar with the history of the American Civil War, 1861-65, it’s necessary that I provide a description of this particularly bloody event of a particularly bloody civil war so to place Quantrill in historical context.

As briefly as possible: For years, even before the outbreak of war between North and South, Kansas had been a cauldron of pro- and anti-slavery sentiments, the scene of murder, intimidation and guerrilla/vigilante warfare by both sides. The preservation or abolition of slavery aside, much of this civilian strife was driven by the opportunities it presented for looting and pillaging.

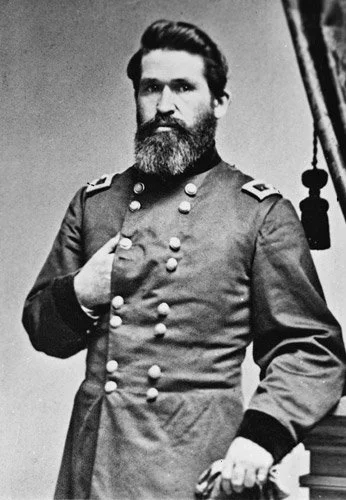

U.S. General James G. Blunt. —The Historical Marker Database, www.HMdb.org.

Union General James Blunt, who was as outraged by the barbarity of the civilian vigilantes who supported his side, the Union, wrote scathingly of a “state of terror” in which “no man’s property was safe, nor his life worth much if he opposed them in their schemes of plunder and robbery”.

In short, Quantrill and his raiders weren’t the only villains in this sad drama.

Lawrence (which had been sacked by Southern sympathizers even before the war, in 1856) was viewed by pro-slavers as the epicentre of abolitionists who waged the terror campaigns cited by Gen. Blunt.

This made it a primary target—not for any strategic military value it may have had—but as a vent for pure hatred and pent-up vengeance.

It was Capt. William C. Quantrill who chose Lawrence as the target and planned the attack. In a letter he later claimed it was “in retaliation for Osceola,” a Union raid on this Missouri town that left it ransacked and nine residents dead after a drum-head trial.

(How ironical it was that, two weeks before the raid, a Lawrence newspaper had boasted that the town was ready “for any emergency” and looked forward to “see Quantrill’s raiders[!]”

Having melded several independent guerrilla groups into a single cavalry force of 450 heavily armed and determined ‘bushwhackers,’ Quantrill set out on a non-stop 24-hour ride. They struck at dawn, Friday, August 21st. So sudden was their attack that they met with little armed resistance and proceeded to round up and shoot the male occupants (one reputedly as young as 11 or 12 years old, some of them on the promise of safe surrender). Victims also included a man who was shot in his sick bed and two who were burned alive in a barn.

Four hours later, when the killing was done and the town looted, much of it was set afire.

One raider was shot as the Southerners withdrew and, the following day, a Quantrill straggler was overtaken and lynched. That wasn’t the end of it, of course. The raid was followed by more revenge killings and more devastation committed by both sides in what amounted to a war-within-a-war.

“Viewed in any light,” the Lawrence Raid or Lawrence Massacre has been termed “the most infamous event of the [U]ncivil War!”

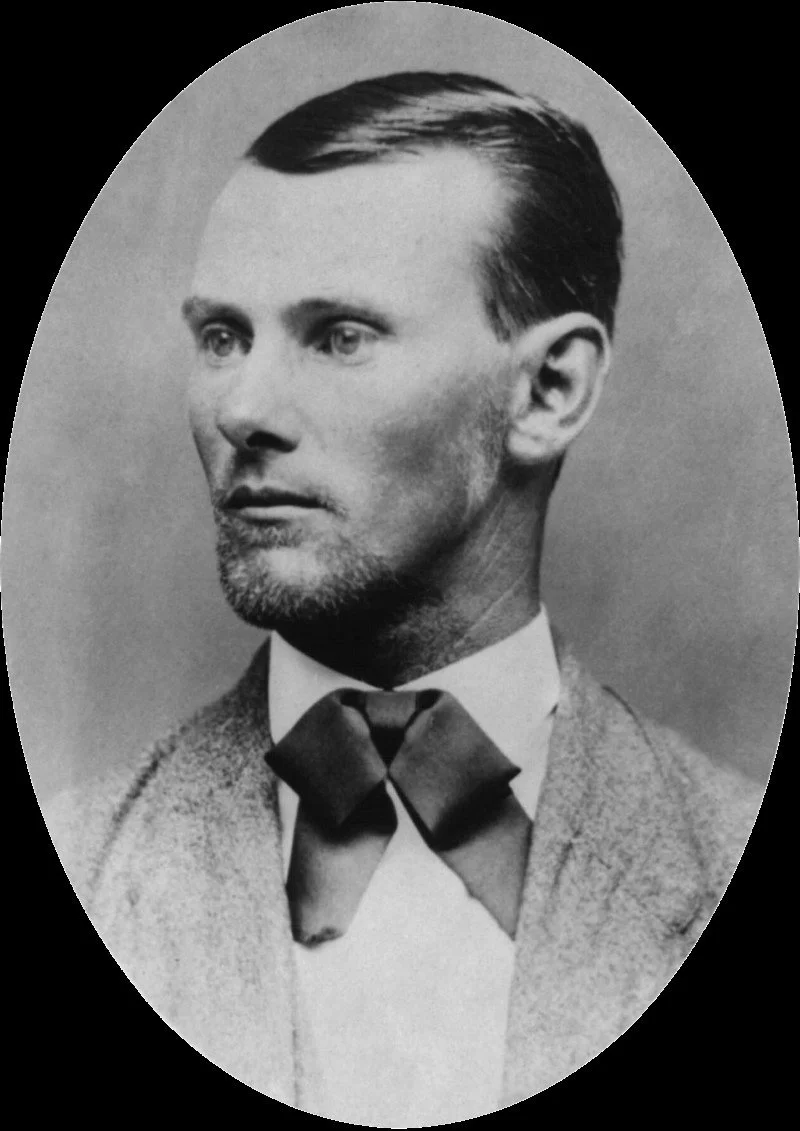

After an unsuccessful attack on Fort Blair in Baxter Springs, Kansas, and the killing of 100 Union soldiers who were part of a relief column, Quantrill and his band wintered in Texas. By early 1865, with most of the guerrillas having gone their own ways, he was reduced to little more than a dozen loyal followers including the future legendary bank and train robbers, brothers Frank and Jesse James.

Quantrill ‘protege’ Jesse James who, with brother Frank, went on to undying fame for robbing banks and trains until his murder by an associate. —Wikipedia

In April 1865 Generals Lee and Johnston surrendered their Confederate armies and the Civil War was, at least officially, over.

But Quantrill and his loyalists fought on or at least sought to evade capture. On May 10th they were discovered sheltering in a large barn by “guerrilla hunter” Capt. Edwin W. Terrill and his Michigan irregulars. It was a classic case of fighting fire with fire, both forces being composed of civilians.

As Quantrill mounted his horse it shied and he was struck in the back by a musket ball that paralyzed him from the chest down. Taking no chances of his being freed or escaping, despite the nature of his wound, his captors transported him to a military hospital at Louisville, Kentucky.

It was there that, at 4:00 p.m., June 6th, 1865, William Clark Quantrill succumbed to his wound. After more than four years of unparalleled savagery, the hated Confederate guerrilla leader was dead at the age of 27.

He was buried in an unmarked grave (since marked) in St. John’s Cemetery, Louisville. Years later, a former childhood friend, William Scott, claimed that he’d disinterred Quantrill’s remains and returned them to his mother in Dover, Ohio in 1887. She is supposed to have identified them as those of her son and, according to Scott, Quantrill was reburied in 1889.

But, because it’s alleged that Scott attempted to sell the infamous raider’s bones, there were persistent doubts as to whose remains, if any, were in the Dover grave. In the early 1990’s the Kansas State Historical Society, at the behest of the Missouri division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, attempted to solve the mystery by arranging for another exhumation.

Grave of Captain William Quantrill in Fourth Street Cemetery, Dover, Ohio. —Wikipedia

Three arm bones, two leg bones and some hair were unearthed but, unfortunately, these weren’t confirmed to be Quantrill’s through DNA testing. In 1992 they were buried yet again, this time, likely the final time, in the Old Confederate Veteran’s Home Cemetery in Higginsville, Missouri.

Final grave of Captain William Quantrill in Higginsville, Missouri. —By KNexus - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12199069

Meaning that, if you’ve been keeping track, the infamous guerrilla leader has not one but three grave markers in three states—Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri!

So ends the amazing saga of William Clarke Quantrill—not.

Because, 50 years later, and almost 2000 miles distant, a Coal Harbour, Vancouver Island caretaker was “recognized” as Quantrill! And many accept that he was murdered as proof of his identity!

The story of John Sharp adds an intriguing chapter to that of William Quantrill. Sharp first gained wide attention in August 1907 when the Victoria Colonist featured the story, “Guerrilla Chief’s Home at Quatsino,” in which it reported that the watchman of the West Vancouver Coal Company’s property at Coal Harbour had been identified as the Confederate terrorist.

American businessman J.E. Duffy, “a member of the Michigan troop of Calvary which cut up Quantrell's [sic] force, “met Sharp at Coal Harbour while there investigating timber limits. Sighting the old man on the beach, he stopped in surprise. ‘Is that you, Quantrill, you damned old rascal!?’

“Come into the house,”replied Sharp, and the two conversed for hours. Duffy later said Sharp had admitted to being Quantrill, and that they’d discussed the dismemberment of his band, Sharp being keenly interested in the Union cavalryman's point of view.

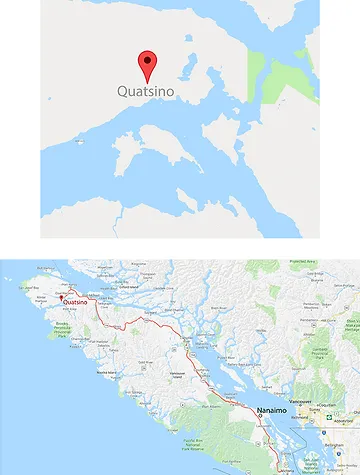

As you can see, Quatsino and area are a long, long way from the state of Missouri. —The Hamlet of Quatsino

(To be continued)

* * * * *