Editorially speaking…

As noted last week, I’m finally working on my tribute to the coal miners of mid-Vancouver Island after 25 years of field and archival research.

This week’s Chronicle about the 1909 Extension mine disaster, and a revisit to Granby two weekends ago, brought back old memories and prompted these reflections on how transitory history can be.

Nothing, as they say, is written in stone...

You stand here today and shake your head. Can it possibly be that this was a model town site? That, 90-plus years ago, these blackened acres just off the Island Highway beside Haslam Creek were the work of a community whose deliberate destruction was later described by a former resident as a “criminal act”?

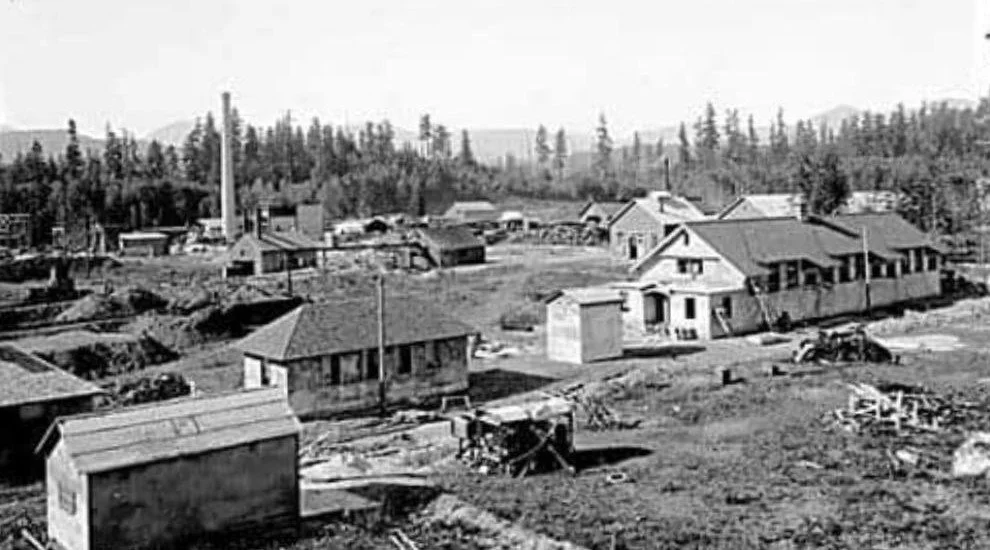

A view of the “model” Granby townsite during construction in 1917. —BC Archives

The fact is, Granby (named for its owners, the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting & Power Company) was everything and more that has been written about it over the past near-century. Photographs show neat, modern homes on boulevarded streets where are now a few modern private homes with third-generation trees.

Across Granby Road, until recent years, were a gravel plain or gouged-out gravel pit and random concrete foundations, now tree-shrouded. What happened?

I’ve told the story of Granby’s short run, 1917-32, as a colliery town, built primarily to produce coking coal for the company’s copper smelter at Anyox, several times over the years. But repeat visits to this historic site and a re-reading of Albert Tickle’s reminiscences of living there have rekindled my sense of wonder at how history can, in effect, come and go.

I can’t help but have a soft spot for Granby, as it was my first real ‘ghost town’. Having grown up in Victoria on American TV and magazines, with their images of frozen-in-time abandoned mining camps, and having learned of ‘Cassidy’ in the provincial archives, I first visited the site with a friend in the ‘60s.

There was little to see, even then, of the Granby of Mr. Tickle’s time.

He’d started work there in January 1919 as a rope rider on No. 2 Slope. That was before the mine was yet in full production. Fortunately for him, he was allowed to transfer to a surface job, to dump loaded coal cars onto the shaker screens which sorted lump from nut coal, then to operate the washers for five years.

One of the few surviving concrete structures at Granby is this loading chute beside Spruston Road. —Author’s Collection

Married in 1929, he and his wife rented a company bungalow on Maple Avenue–two bedrooms, living room, kitchen and bathroom–with stove and electricity provided, for $17.50 (three days’ pay) a month, coal for cooking and heating extra.

Two families, three teachers and single men occupied the handsome, two-storey California-style boarding house “with all the facilities”. The dining hall with dance floor and player piano also served for concerts and meetings. Personal laundry could done be in the company wash-house and other amenities included store, theatre, library, barber shop, pool hall, Catholic church (used but a few times) and, initially, a hospital, as well as tennis courts and a football field in a community that had to be self-contained as its nearest neighbours were Ladysmith and Nanaimo.

Dominating the landscape was the boiler house smokestack, said to be one of the largest in Canada.

A combination of things did Granby in in just 15 years. Although a nice place to live, it was a dangerous place to work, with frequent gas blow-outs. So volatile were the Granby workings, in fact, that explosives couldn’t be used in some of the underground workings and communication was by hand-bell rather than by electric buzzer that could have sparked an explosion.

Nevertheless, although its casualty toll pales alongside that of other Island collieries, the human cost of extracting 2.5 million tons of coal (an average of just over 163,00 tons annually) was, I’ve determined so far, 19 lives. Other contributing factors were declining cost-effective coal reserves, the arrival of the Great Depression, falling coal prices, the increasing use of petroleum and electricity, all compounded by the impending closure of the Company’s copper works at Anyox.

In an attempt to stave off the inevitable, when it became apparent that the original workings were becoming too expensive to work, Albert Tickle wrote, the company had started a new mine, No. 2 Slope, on a smaller scale at the back of their property. This had entailed moving several houses in what would be a foretaste, alas, of the town’s fate just a few years later, in 1936.

They had to bore through solid rock in a time-consuming and expensive bid to reach a new seam, even as they withdrew from the No.1 by removing the pillars of coal originally left untouched as roof supports. But, in September 1932, after just nine months in operation, No. 2 was also closed.

So the Granby of old is gone, its houses sold and torn down in 1936 to be, for the most part, rebuilt elsewhere. The manager’s grand house on the hillside overlooking the town, said to have cost $30,000, was recycled in Nanaimo and has heritage designation. (It would be interesting to know the ultimate placements of all these houses.)

Of Granby, Albert Tickle mourned: “It was one of the loveliest townsites on the North American continent, what a pity to see such waste.”

The Granby that survives is a small community of a half-dozen or so homes dating from 1946, and all drawing their water from the original company pump house beside the Nanaimo River. They even have their own fire truck. But there’s little to see of the good old days when Granby, Cassidy was a producing coal mine with its own unique and vibrant residential community.

We humans like to think we build things to last forever; we never seem to learn that nothing, really, is written in stone.

At least, thanks to the late Albert Tickle, Jack Ruckledge, archival records, the Stupich family and old photos, some of the memories live on.

* * * * *