The Day the Mine Blew Up

A wander through the Ladysmith Cemetery and you see it, not once, not twice but again and again: the date, October 5, 1909.

That was “Ladysmith’s Day of Horror” of 116 years ago when, as B.A. McKelvie wrote in the Vancouver Province in 1957, The Mine Blew Up.

Belinda examines a headstone in the Ladysmith Cemetery where many of the victims of the 1909 explosion are interred. —Author’s Collection

In this week’s BC Chronicles I’m going to let Mr. McKelvie, once considered to be B.C.’s premier historical writer, tell you the sad and dramatic tale of that October day when 32 men perished in the Extension Mine.

* * * * *

Oct. 5, 1909 began as a dull, uncomfortable day. There was a slight drizzle as merchants of Ladysmith opened their stores, and the first suggestion of coming cold weather was felt in the gusts of wind.

But, despite the weather there was a feeling of optimism in the little city that depended upon the operations of the Extension mines of the Wellington Colliery Co. for its maintenance.

There was an increasing demand for coal, especially in the great San Francisco market that had been served by Vancouver Island mines since 1853. Then, too, Vancouver, the bustling railway terminal on Burrard Inlet was growing at a phenomenal rate, and was boasting that next year its population would number 100,000; and that meant an enlarged demand for coal.

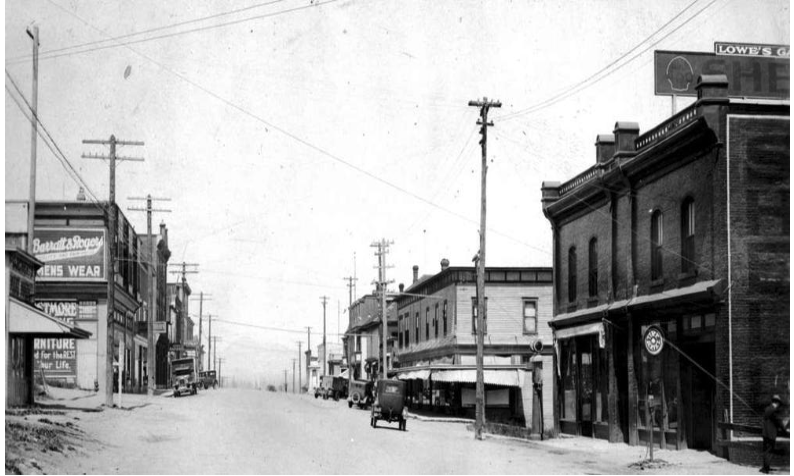

Ladysmith’s First Avenue.The BCA dates this photo as 1911 but the vehicles suggest the 1920s. —BC Archives

There was another cause for satisfaction in the mining community that was already looking forward to Christmas. It was the remarkable falling off in the number of accidents that seemed to be incidental to the working of coal seams. Not since August 26 had Number 7’s wail of distress been heard as the engineer signalled he was bringing in a casually in order that Dr. A.C. Frost might hasten in the town’s only automobile to the station to receive the wounded worker.

When that screech sounded over the hillside homes women froze, and mumbled prayers that the dread constantly dwelling in their minds was not to be realized. Men, hardened by years of danger in the blackness of the pits, would choke and mutter: “Wonder who it is this time—and how bad?”

* * * * *

Now, shortly after 9:00 on that bleak October morning, the accident-free operations came to an abrupt and terrible end. As Engineer McKay brought Number 7 swaying around Smelter Bend to a sudden stop, Dr. Frost and several officials of the company were waiting in a serious-faced group. They climbed aboard the single car as the engine turned at the ‘Y’ to re-couple the coach and dash off for Extension.

Those seeing the quick departure of the doctor and officials sensed the import of the speeding locomotive; something was wrong at the mines!

The fear was communicated from lip to lip and in a few minutes had spread throughout the mining population. People surged from their homes, and along First Avenue, the shops emptied, as everyone begged his neighbour to tell him what had occurred.

“Number 7 came in for Dr. Frost and some of the bosses,” was the only factual information that was available.

* * * * *

Men, women and children milled about on the sidewalk outside of the Stevens’ Block; then someone suggested, “What do they say at the office?” and a number hurried off to the pay-office on the Esplanade hoping to learn the news from William Russell or Wyman Walkem of the accountancy staff. But all that was known there was that there had been a big accident; there were no details.

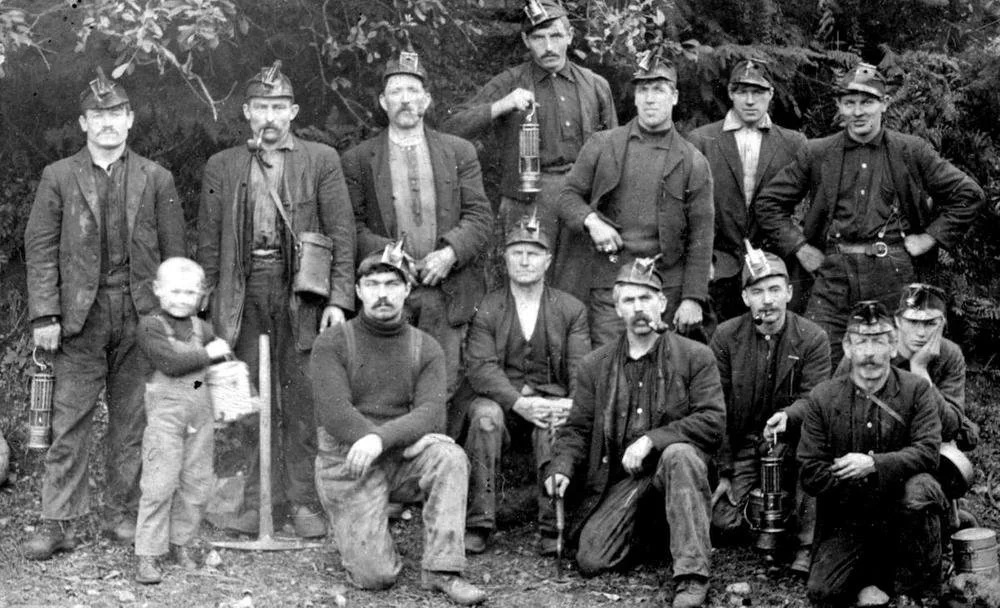

Incredibly, you worked underground in street clothes, without helmets and with open-flame lamps. Let’s hope that the little boy is just posing with his dad. ‘Boy’ miners were legal in B.C. but they had to be 14. —BC Archives

Something had had, indeed, happened. It was shortly after 8:30 a.m. and the day-shift workers were at their respective places and duties when there was a fall of coal several hundred feet in length from the roof of No. 2 1/2 West level that sent disturbed air shuddering through the passage and ventilation ways of large sections of No. 2 and No. 3 mines.

Miners knew what it portended, but before they could make more than two or three steps in flight—flight in darkness, for the wind had extinguished every naked light, the illumination used generally underground at Extension—there was an explosion, and flame flashed along some levels, burning several.

Then came another concussion as another section of more than 200 feet, separated by only 36 feet from the previous fall dash of the roof, fell. This aided in pushing the poisonous after-damp—oxygen-exhausted air—through the passages where men were feverishly seeking escape.

While men staggered blindly along the levels underground, and died—32 of them—outside, overmen, fire-bosses and others of experience and authority were organizing rescue teams. Manager Andrew Bryden with Overman Bill Jones of No. 1 Mine; Alex Shaw of No. 2 where the explosion had taken place...were joined later by Chief Inspector of Mines Frank H. Shepherd, Inspector Archie Dick, who had raced over from Nanaimo, as had Tom Graham, manager of the Western Fuel Company’s mine at that place.

There were no oxygen-supplied gas masks; no special equipment for combating the deadly fumes that followed an explosion—only the courage and practical knowledge of brave men. And of these there was no scarcity. Every man and boy knew that three breaths of after-damp might be fatal, but the call for volunteers—from among the men who had fought their way to safety and had staggered out of the tunnel to fresh air—was answered with a spontaneous offer from all.

* * * * *

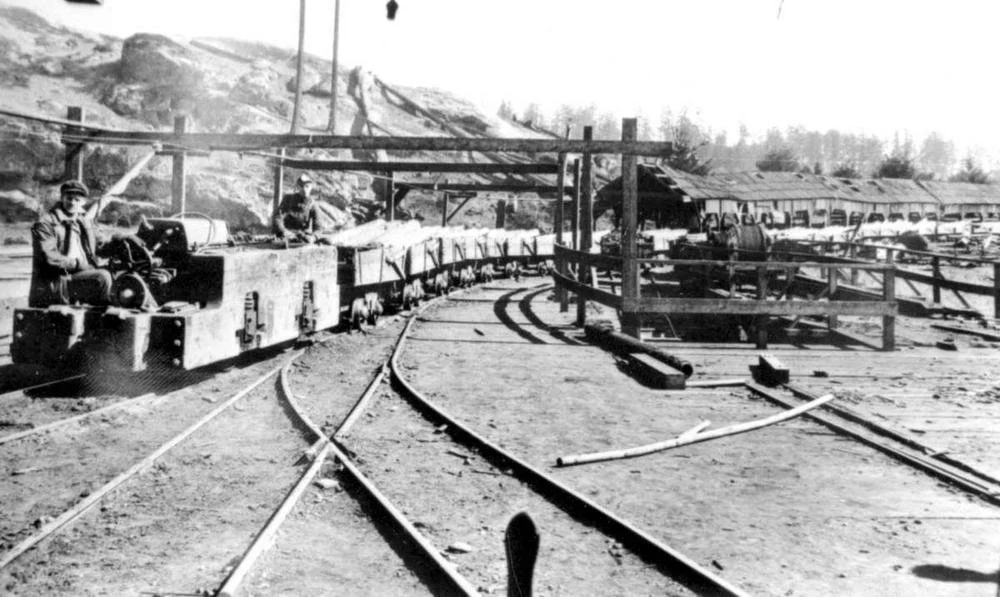

At the entrance to the No. 1, 2 and 3 Extension mines which were connected underground; the fatal explosion of 1909 occurred in No. 2. —BC Archives

Only the most experienced men were selected, and these groups headed by overmen who knew every foot of the workings under their charge, disappeared into the tunnel to separate into the different mines at the “Cog,” or end of the main haulage tunnel.

This rare photo of a miner at work in the Extension Mine was taken a year before the disaster of 1909. —BC Archives

It was not very long before word came to the surface that the body of young Eddie Dunn, a driver, had been sighted. He lay with his hand beneath the car—but his mule was not there. The animal had escaped.

Then the bodies of others were found; that of James Molyneaux being the first brought out of the mine. Molyneaux was a former Grenadier Guardsman who wore the medals of the Sudan and Boer Wars.

Shortly after, two other popular young men were carried out: Fred Ingham and Tom O’Connell, Jr., the young manager of Ladysmith’s most famous football club.

Tom was found with his arm about the body of Andrew Moffatt, a friend whom he was trying to help when they were enveloped by the lethal gas.

Bob White, O'Connell's brother-in-law and father of six children, also gave his life for a friend. He had been with a large party of men trying to escape but a small number thought they would try another route. Bob's inclination was to stay with the larger group, but John Isbister, his chum, wanted to go with the others, and Bob White would not desert him. They found him—like Tom McConnell—in the attitude of assisting his friend.

Something of the fearsome fight for life in the dark was described by several of those who escaped.

Thomas Hislop was one of a group rescued by Overman Alex Shaw, his brother Jimmy and John Davidson, whose son William did not come out from the scene of the explosion. It was hours after he had been piloted out of the tunnel mouth that Hislop told his dramatic story. He was still waiting about the mine, hoping against hope that more of his friends would appear.

These Extension miners were photographed at work in 1908, a year before a devastating explosion killed 32 of them. —BC Archives

* * * * *

“Bob White, he drops his pick and shouts, ‘My god, she's blasted,’ Hislop said in telling of the first intimation that the miners had of the explosion. “We stood for a second in the darkness. The rush of the wind put our lamps out, until someone came with a safety lamp and 15 or 17 of us, holding to the coat-tail of the man in front, started.

“We hurried along holding the lamp so we could see the glistening of the rail, but we were driven back. A great cloud of smoke blew into our faces and we got a whiff of after-damp, and we knew we must go back.

“To the counter-level we went, but we could not get through. The damp drove us back into the level again. We tried to clamber up in No. 10 Stall, across to the crosscut, but were driven out. In No. 3 Counter-level we left Alex McClelland, Wynne Steele, Fred Ingham and Bob White. When we left them we did not know the damp had got them.

“We knew nothing then except that the smoke and damp were chasing us whichever way we went. We struggled on, though after a while, being mostly lost.

“Finally we sat down to figure what could be done. We were tired and beaten back. Then the fire-damp became so thick that it couldn't be faced and we had to run back from it. Then we decided to remain and wait for relief—or for death. We had not been waiting long when we heard the shouts of Alex Shaw, the overman, and John Davidson.

“We answered, and with them instructing us, we smashed through the stopping and crawled over to safety. We clambered out up the slope, clinging to each other's coat-tails, and helped by men who met us with safety lamps. We waited at the slope head, but the five others never came out."

David Irving, another experienced Scottish miner, who was one of the same group as Hislop, paid tribute to the heroism of Alex and Jim Shaw, and Davidson.

“I had gone to the counter-level from the main level where I had been working, but the rush of wind which followed the concussion put out my naked light,” he explained. “I had a safety lamp at the face and when the man who had been working in the counter-level came, we went together and got my lamp. Then Davidson called and said to get him, but when we came to his place he had gone.

“We picked up another man, Dewar, and we all tried to get to the same main level, but the damp, growing hotter, beat us back. We went back to where we came from and were joined by Radford, Hillis, Matt Gilson, Robert Smith, Robert Cameron, Thomas Hislop and an Italian we know as ‘Paul.’ We all made our way to No. 4 Level and met there.

“There were two safety lamps in the party and with these leading we tried to get to the counter-level but were beaten back again by the damp. We tried to clamber up the hill to No. 12 Stall, but there came a rush of wind and damp through the connecting crosscut that put my lamp out. We thought the end had come and went back, gradually forced by the gas, until we came to a place where there was some air, and sat down.

“We had given up and were talking. It was this talking that saved us. The Shaws and Davidson heard our talk and they broke off a board from the stopping and let us through to safety.”

All day the rescue parties heroically explored the workings seeking any who might be alive, while others risked their own lives to repair damaged curtains and stoppings in order to direct fresh air current into the depths of the mine to clean out the poisonous gases.

The days that followed were trying ones in Ladysmith; from early morning until after dark, funerals wound up over the hillside and out the wooded road to the cemetery, while church bells tolled, and the weary members of Ladysmith’s band played The Dead March. And for days and weeks a coroner’s jury and many mining experts sought to find the cause for the deaths of the 32 men.

These Ladysmith miners, photographed a year after the disaster, are lucky—they get to go home at the end of their shift. —BC Archives

There were many theories advanced, and experts disagreed, though accepting the same set of facts. The two cave-ins along No. 2 1/2 West level, it was stated, had liberated some gas, and this, ignited, probably by a naked light, had exploded. But the unanswered question was: “What caused the roof to fall?”

It was found that along the roof of No. 2 1/2 Level the coal had “rolled”. It was folded and friable—but what brought it down? Was the explosion responsible or was the fall of coal the cause of the explosion? There had been an earth tremor that morning, the meteorological station at Victoria reported. That may have been responsible, and many thoughts so.

But six months after the explosion, in clearing away the debris and rubble from one of the rooms, a blown-out shot-hole was found. So it was decided that a miner had loaded and fired a shot without waiting for the arrival of the fire-boss to inspect the hole and the charge. His eagerness to break down coal had cost him his life and had taken the lives of 31 of his fellow workers.

Ladysmith never recovered from that explosion. James Dunsmuir, the head of the [mining] company was so shaken by the tragedy that he sold all his coal properties not long after, to the Canadian Collieries (Dunsmuir) Ltd.

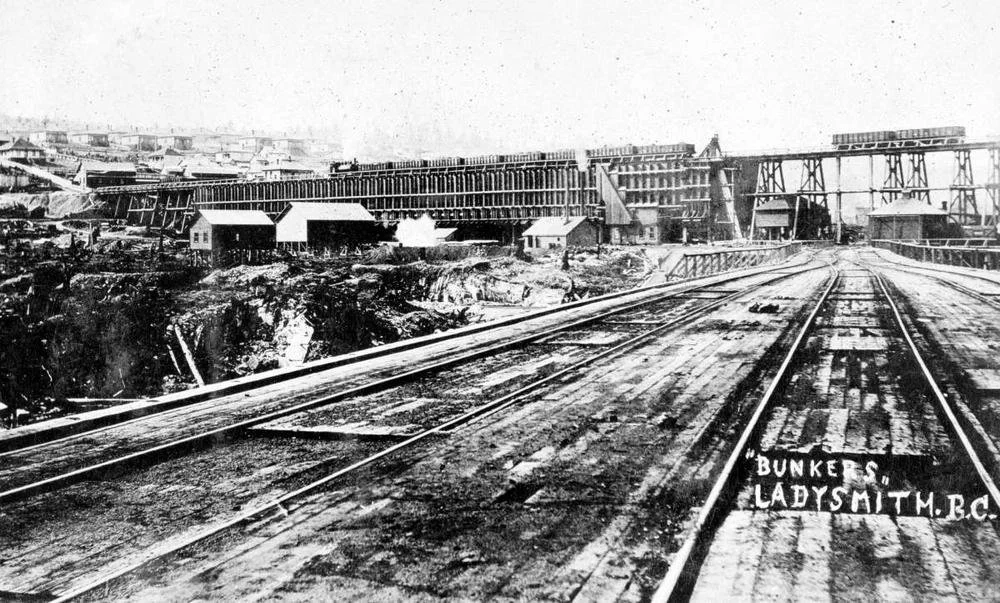

No more does Number 7 with a long line of loaded coal cars steam down from the mines to the big loading docks; no longer do big cargo carriers steam out of the harbour for San Francisco's ready market; the great wharves where freighters took on bunker coal have disappeared.

People now picnic where the massive coal bunkers once dominated the Ladysmith harbour front. —BC Archives

Ladysmith’s prosperity today is measured in terms of forestry products—but as long as any of those who called the hillside city home in 1909 are alive, the tragedy of that bleak October day in 1909 will not be forgotten.

* * * * *

So wrote B.A. McKelvie in 1957. I can take issue with some of his interpretation of that horrendous day in Ladysmith history but I’ll save it for my own take on the Extension disaster in my book, Along the Black Track.