Fighting John Copland – Barrister and Brawler

Situated on Vancouver Island’s west coast, between Long Beach and Ucluelet, Florencia Bay (until 1930 known as Wreck Bay) marks the final resting place of the Peruvian brigantine of this name.

Callao-bound with a cargo of Washington lumber, her agony began at the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in December 1860. Gale-force winds caused her to heel over so far, and so violently, that Capt. J.P. de Echiandeia, her supercargo, cook and a passenger were drowned.

Only her cargo kept her from going under.

As the lumber became waterlogged, the stricken brig righted herself and, caught by prevailing northerly currents, drifted into Nootka Sound where her crew anchored, pumped her out and found that she was sound but for the loss of her masts.

Word of her situation was carried to Victoria by a passing yacht and Her Majesty’s gunboat Forward steamed to her rescue. Once at Nootka, however, Lieut.-Cmdr. Charles Robson learned that the American brig Consort had wrecked near Cape Scott. Deeming her needs to be greater than those of the Florencia, then safely at anchor, Robson sailed north, rescued the Consort’s company and returned to take the Peruvian in tow for Victoria.

But a boiler malfunction forced Robson to cast her loose and, despite the heroic efforts of her crew, Florencia crashed ashore on an island in the bay which today bears her name. She was a total loss but for her cargo of lumber.

(Upon the makeshift repairing of her boiler, HMS Forward returned to Esquimalt after circumnavigating the Island; Cmdr. Robson had yielded to headwinds, rounded Cape Scott and steamed south through the Inside Passage. Forward had been gone so long that she and her company had been given up as lost.)

Such was the fate of the good ship Florencia.

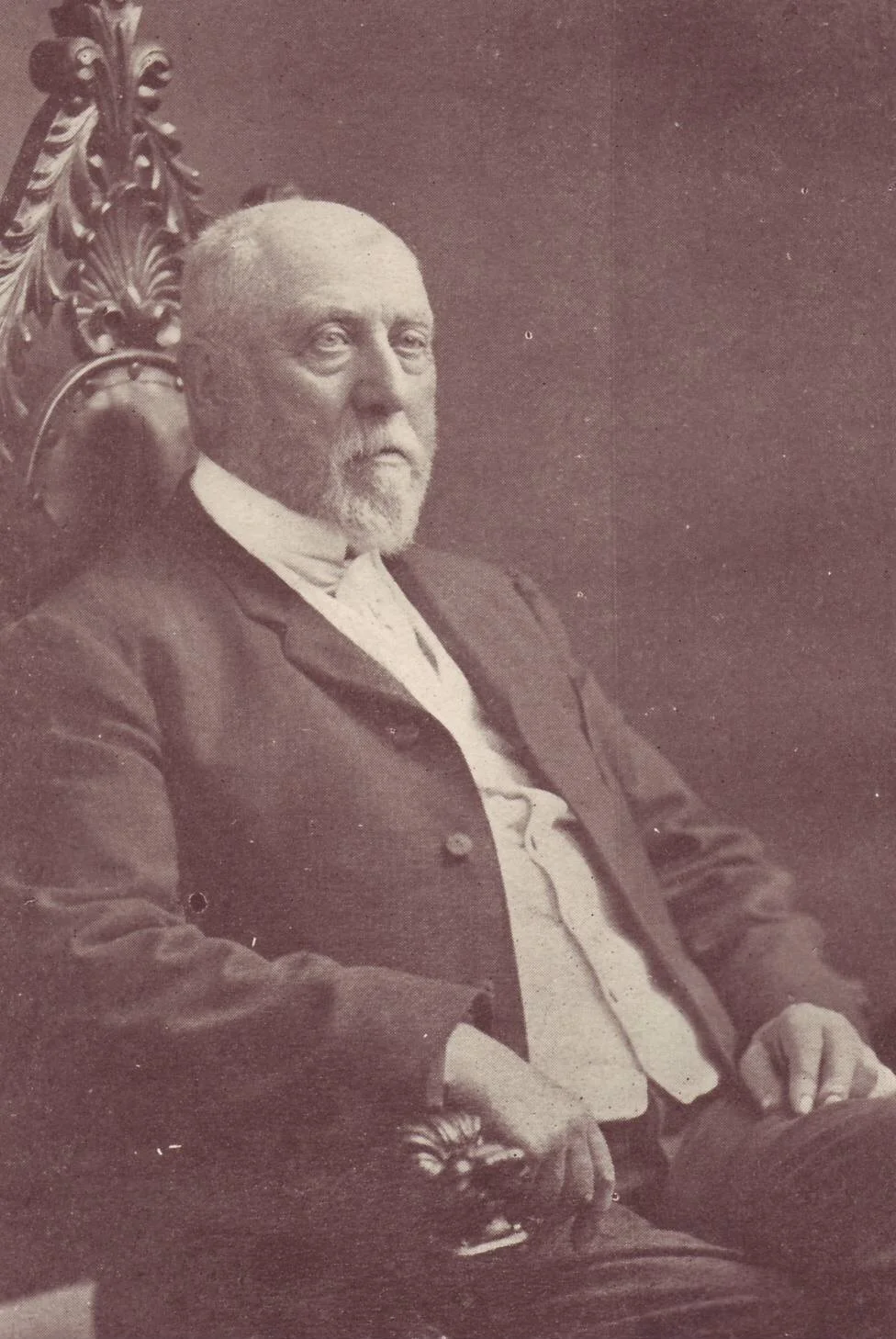

Our old friend D.W. Higgins is back with another illuminating tale of earlyday Victoria, this one about barrister John Copland and his equally fiery wife. —Author’s Collection

For the story within a story, we’re indebted to Chronicles friend and pioneer journalist D.W. Higgins and his entertaining book, The Mystic Spring, published over a century ago. He recounted the misadventures of John Copland, Victoria barrister, city councillor and one of the capital’s most outrageous characters ever. John, you see, had something of a temper. Once crossed, no matter how slight the provocation, it was to battle stations and no quarter given.

Encouraged by his shrewish wife, he kept Victorians of the 1860s enthralled with his many joustings. His ironic involvement in the loss of the Florencia began when the invitations to a ball were sent to all the prominent men and women of Victoria–everyone, that is, but the Coplands. Upon demanding to know why, they were informed that the executive of the Social Guild (which Mrs. Copland had founded!) had learned that she had a past–thus she was unworthy of membership and a ticket to the ball.

Mrs. Copland became hysterical and almost fainted.

John, ever the man of law (and obviously one who believed in the adage, ‘don’t get mad, get even’) announced that he was going to sue the husband of the Guild’s president for slander.

Other than that Dr. T.B. Baillie’s wife was secretary of the Guild, Higgins doesn’t state whether Baillie–“one of [Victoria’s] oldest and most esteemed residents”–played an active role in defaming Mrs. Copland. It probably didn’t matter to John, who was determined to have satisfaction in court.

Asked by Higgins if they’d consider an apology, Mrs. Copland replied, “Never–never! If he lay dying and asked me to forgive him I never would.”

Less than two weeks later, the popular Dr. Baillie was dead–one of the ill-fated Florencia’s four victims. Unnerved at the thought of Copland successfully suing him for damages (debtors faced prison in those days), Baillie had secretly booked passage on the South American bound brigantine. When she was thrown onto her beam ends off Cape Flattery, Baillie was swept away.

Many Victorians held the Coplands responsible for Baillie’s death. Because of the doctor’s popularity, that of the battling couple–already nominal–sank even lower...

* * * * *

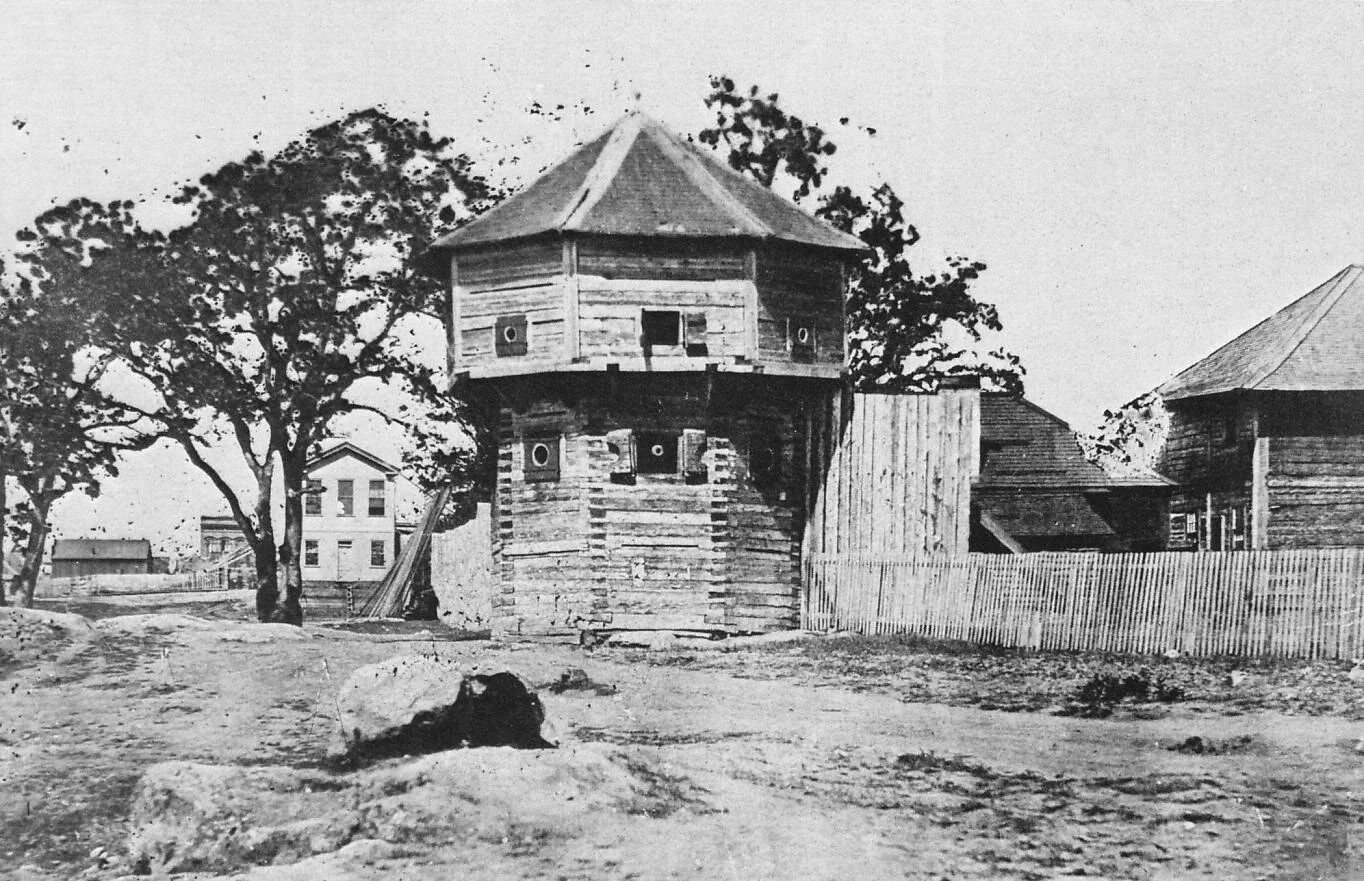

Victoria, the future capital of British Columbia, was still a Hudson’s Bay outpost when the Coplands inadvertently entertained its citizens with real-life comedy and drama. —Author’s Collection

Not a particularly humorous introduction to a man whom I promised last week would make you chuckle. Please bear with me; we’ll see whether, with the help of D.W. Higgins, you can resist a smile when I finish telling you more about John and Mrs. Copland...

Although the fiery Coplands made ‘copy’ time and again in the British Colonist, most of the news reports are quite dry and concern John’s jousting in the legal and political arenas. It’s fortunate for posterity that Higgins has left us a graphic, blow-by-blow account of the Coplands’ stormy tenure in outpost Victoria—a residence which, “in the absence of a theatre...caused the keenest amusement to the residents”.

The antics of the oft-maligned Coplands were, in fact, better than television.

Surprisingly, journalist Higgins has left but the scantiest description of jousting John Copland (or John Colber as he named him in 1904), stating only that, 35 years before, Copland was a Scot, of sturdy build and about 40 years of age. Mrs. Copland, some 10 years his senior, drew a considerably more detailed description, Higgins apparently remaining awe-struck decades later.

“She was a little Englishwoman, of quick, nervous action, black snappy eyes, and a tongue—as old Willis Bond the famed coloured orator

who once came under its lash, expressed it—“dat cuts bot ways like a knife”.

They had arrived in shack-town Victoria in the summer of 1859. Having some means, they erected a small dwelling at the northeast corner of Langley and Bastion streets, the “shack” doubling as both residence and law office.

From this ungainly headquarters (which did not suffer by comparison with its Victoria contemporaries) Mrs. Copland mounted a campaign to establish herself as a social leader by hosting teas (then an innovation according to Higgins) for the prominent ladies of Victoria society. They met regularly with the avowed intention of creating a social register whereby they might separate the wheat from the chaff from the 100s of newcomers who were pouring steadily into Victoria.

These ladies, it seems, felt that, “in the hurry and bustle of strangers arriving and settling here some very undesirable persons had succeeded in imposing themselves upon society and were carrying their heads high when were the truth known, they should hang them very low.”

The natural leader of this social secret police was Mrs. John Copland.

Alas, her own slip was showing; when invitations to a ball in a renovated Hudson’s Bay Co. warehouse were issued, the Coplands weren’t included!

Worse, it seems that Mrs. Copland was now excluded from the very guild she’d organized. It, having met secretly, had weighed evidence put before it by a recent arrival from Australia who said that—really!—Mrs. Copland had a past. On that evidence, no matter how scant it may have been, the good ladies of Victoria protected their own reputations by dropping the Coplands from the guest list.

Well, to say that the Coplands were upset is to put it mildly. They were, in fact, livid, and, in righteous rage, descended upon the house of the guild’s secretary who’d been in charge of issuing the invitations.

Even the best part of half a century after, Higgins couldn’t conceal his delight when he reported that the woman of the razor-edge tongue met her match in the secretary who drove her, hysterical, from her door amid a barrage of unflattering remarks.

Vanquished, Mrs. Copland had had to be helped home by the equally stunned barrister. Although no amateur at oratory himself, particularly in a courtroom, John seems to have retired in confusion also.

But, unlike his wife, he soon regained his composure—and his temper—and he launched a suit against the secretary’s husband, Dr. Baillie, for defamation of character.

The result, as described in the preface, was death by shipwreck for the popular doctor who’d fled the colony to avoid being found guilty in court and ruined financially.

The result for the Coplands was further estrangement from the Victoria establishment which held them responsible for Baillie’s death.

Today’s entrance to Bastion Square is very close to where the Coplands had their home and the adjacent store whose fence, they believed, encroached on their lot by all of three inches. —By bynyalcin, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54808394

But life went on and Baillie was soon forgotten when Copland embarked upon a new crusade against a neighbour whose brick building, situated on the corner of Government and Bastion streets, backed upon the Copland property. The reason for their feud was Copland’s belief that the other’s fence line encroached three inches onto his lot—an infamy which, according to the feisty barrister, justified full-scale warfare.

And the battle was on!

It so happened that the offending neighbour employed a young man named Hicks in his store. As the feud between his employer and the Coplands grew in intensity, it fell to Hicks’s lot to hold the fort—literally—during his employer’s absences, And, as Higgins made perfectly clear, Hicks accepted his new responsibility with enthusiasm, apparently welcoming the Copland threat as a novel way to stave off boredom.

He was, alas, soon to regret his becoming involved.

“After the passage of numerous fiery epistles, Mrs. Copland cow-hided Hicks on Yates Street, and was fined 5 [pounds]. Next, Hicks and Copland met and Hicks pulled his antagonist’s nose, for which luxury he paid 5 [pounds]. Then Copland printed a card in which he referred to Hicks as a man who had been publicly cow-hided. Hicks retorted with a letter in which he referred to Copland’s nose as having been tweaked on the public street.

“In the absence of a theatre the controversy created the keenest amusement in the residents and while one party would pat Hicks on the back and advise him to keep it up, another section would tell the Coplands to give it to him.”

More whipping followed when Copland found “some slops” in a puddle at his back door, accused Hicks of having thrown them there and addressed him as “a pup”. The following day, Hicks spied his opportunity for revenge as Copland passed the shop and, rushing into the street, whip in hand, bellowed, “Sir, you called me ‘a pup,’ and I promised to cow-hide you. I now fulfill my promise.”

With that, he brought the whip down across Copland’s back, not once but twice. Fortunately for Copland, a thick coat prevented his suffering injury to more than his pride and, closing with his assailant, he struck him a light blow across the head with the stock of his hunting whip. [Then an article of men’s fashion, believe it or not.--TWP] At this point both combatants were spared further indignity when a third man, M. Winkler, intervened.

Magistrate Pemberton made a fourth when he fined Hicks 20 shillings for assault, the latter paying “like a man”.

And so it went, the belligerents proceeding from one outrageous encounter to another as their friends encouraged them to continue battle to the end. Ironically, the end came sooner than expected when the cheeky Hicks made a grave tactical error one day; upon finding a dead cat in his employer’s backyard, and not unnaturally assuming it had been thrown there by the dastardly Coplands, he hurled it over the fence into the others’ yard.

Unfortunately for his time and his aim—or so he claimed—at that precise moment Mrs. Copland and a helper were engaged with a tapeline, measuring the contested fence line in a further attempt to prove that their lot had been cropped by three inches.

That’s when the deceased feline sailed over the fence and landed on her head.

Receiving a “severe serious shock,” to quote the chortling Higgins, Mrs. Copland screamed in terror as she imagined herself attacked by a ferocious beast. Within seconds, Copland was to the rescue. Instantly sizing up the situation, and after soothing his wife’s fears, he seized the corpse by the tail and raced around the corner to the store where he found Hicks casually standing in the doorway.

Confronting the young dandy—who quailed before his wrath—with the evidence, Copland proceeded to soundly thrash Hicks about the head and shoulders—with the cat.

Chuckled Higgins years later: “The town went wild with delight! The comic side of the controversy always applies most strongly in the popular mind, so the funny incidents of the cat and the use that was made of it took the public by storm. Nothing else was talked of for many days and the ‘sic him, boy!’ tactics were continued by the friends of both.”

But Hicks seems to have retired from the field, battered and bruised, leaving Copland triumphant and, in characteristic fashion, in search of a new foe. Between skirmishes, in and out of the courtroom, he found time to take advantage of the 1862 boom to speculate in real estate, buying two large lots on Pandora Street then flipping one for the price he’d paid for both. With the proceeds he erected a substantial two-storey building at Langley and Bastion streets in place of their modest home.

In fact, 1862 seems to have been a vintage year for the Coplands, with John even being elected (with the highest number of votes) to the first city council under Mayor Tom Harris, the towering 300-pound “’umble tradesman” with whom Copland was to soon cross swords.

An unhappy choice of an opponent as it turned out; as a professional butcher Harris was no stranger to cold steel—or sharp words.

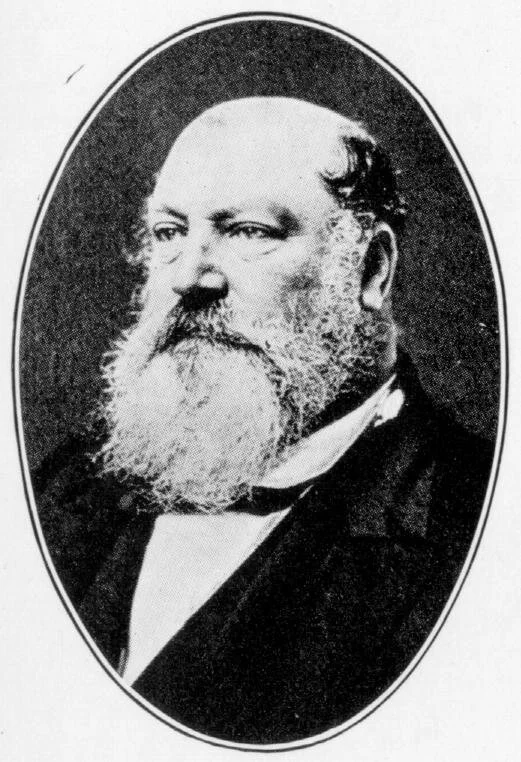

Tom Harris, Victoria’s first mayor, butcher by trade, wasn’t afraid to stand up to the blustering John Copland. —Wikipedia

The election, coinciding with the Prince of Wales’s 21st birthday, provided good reason for an inaugural ball. Briefly: all proceeded smoothly, with a happy turnout of 200 leading citizens, including Gov. James Douglas, officers of Her Majesty’s ships moored in Esquimalt, and Mayor Harris and council.

After the dinner came the speeches—and trouble.

First to speak was Attorney General George Cary who was followed by Mayor Harris. But when a fellow councillor rose to speak for Council, Copland rudely interrupted, “As senior Councillor the duty devolves upon me to reply to the toast.”

“You are out of order,” snapped Harris.

“Oh, no, I’m just in order as senior Councillor.”

Throughout the uproar, he remained standing and calmly surveying the bedlam until Gov. Douglas, Bishop Demers, the French Consul and the naval officers left in disgust. Then Mayor Harris boomed: “Will no one remove that nuisance?”

“At this,” Higgins, who was present that evening, recounted with a laugh, “a rush was made for the senior councillor. A dozen hands were laid upon him and a mob of 30 men closed in upon the ‘nuisance’ and threw him bodily out of the hall. As he struggled to release himself, the high soprano of his wife was again heard as she rained an orange, an apple, a cake and a plate upon the guests below, and then dashed down the stairs and, throwing her arms about her husband, led him towards their home, calling down heaven’s maledictions on his assailants as they went.”

And with that, Victoria’s first mayoral dinner was history!

But not so the belligerent John Copland’s career. Not one to be bowed by such a minor embarrassment as being thrown bodily from a banquet, he was soon in difficulty with another antagonist.

An outline of John Copland’s antics forms a calendar of comedy: Elected president (obviously not everyone disliked him) of the St. Andrew’s Society, he commenced legal proceedings for defamation of character against two of its officers, for which he was roundly censured by the executive which demanded his resignation. He refused.

In June 1861, he was again in court—not as a legal advisor but as an active participant, the battling barrister having accused William Muir of assaulting his wife. Muir had countered by charging Mrs. Copland with having assaulted him. The seed of dissent, this time, was nothing more than “the attempted removal of some sand from in front of Mr. John Copland’s house by Mrs. William Muir, “which has created not a little talk and tea-table gossip for a week past,” reported the Colonist.

When all had had their say, Magistrate Pemberton dismissed the Coplands’ charge against Muir but accepted Muir’s charge against Mrs. Copland and fined her 20 shillings.

At this, an indignant John jumped to his feet to demand an appeal which, an exasperated Pemberton denied. Spluttered Copland: “Then, sir, I shall appeal to the governor: this is the fist time I have ever known an English court to refuse an appeal!”

When Pemberton warned him against committing contempt of court, the Coplands reluctantly retreated, John still vowing to take his wife’s case to a higher court.

Only John Copland could have been charged with assaulting an antagonist in court, William Culverwell having accused him of striking “him several times on the shoulder at the same time saying to him, ‘Now, young man, etc.’” Unfortunately for Culverwell, despite lengthy testimony and cross-examination, he failed to prove his point.

But, within three months, John was in difficulty again, this time enduring the ire of Mayor Harris and city council whom he’d snubbed by not inviting them to a lavish party. Then, come election time, John decided to fix Harris’s wagon once and for all by running for mayor. Alas for John, when the votes were tallied, Harris had been returned with a seven-fold majority.

One unhappy election campaign followed another, Copland never again achieving public office; this, despite the fact that, when running for mayor against Lumley Franklin, he polled a majority of votes. But, for all of his protests and involved legal arguments, Franklin assumed the office.

At least John did enjoy the odd personal victory, such as the time he was charged with having assaulted a Mr. Cooper by seizing him by the neck and heaving him from his office. Due to the fact Cooper had used unflattering language, the court ruled that Copland had been justified in ejecting him.

But there was tragedy in the offing.

During the construction of their new brick mansion on Pandora, John learned that the Jewish community planned to build a synagogue next door—a synagogue which would be taller than his house. Thus threatened with eternal shade, John immediately ordered his contractors to add another storey, that Mrs. Copland might “always command a fine view”.

Congregation Emanu-El, Victoria, is still there but the ill-starred Copland mansion is long gone. —Wikipedia

As the manor neared completion, Mrs. Copland visited the site almost daily until she impulsively decided to climb a ladder to the unfinished roof to enjoy her future view. Suddenly, some un-slaked lime fell from above and into her eyes. Screaming in pain, she was rushed to a doctor. But the damage was done and Mrs. Copland of the blazing black eyes was blind. Ironically, as Higgins wrote years later, “other eyes have feasted on the view to be had from the roof, but the lady for whose pleasure the elevation was increased never saw again.”

A second disaster befell the Coplands early in 1866 when their home was burglarized of $3500 in cash and jewels—half of which belonged to a client. Despite a frenzied manhunt, neither money nor jewels were recovered.

And with these misfortunes John Copland’s spirit seems to have been broken, his will to do battle weakened. In November of the same year, his ”two substantial brick houses on stone foundations, built...at a heavy expense and large outlay, with the very best materials and workmanship,” were put up for sale.

Throughout this trying period, according to Higgins, “The devotion of John Copland to his blind wife was marked and touching.

“Her temper, never of the sweetest, grew worse under great misfortune: but Copland put up with everything and was accustomed to lead her with an exemplary tenderness and patience through the streets for an airing or to and from church.”

Sad to say, it had been during one of these brief excursions that they had been robbed.

Then the Coplands departed from Victoria, bound, so Mr. Higgins believed, for Australia where, some years after, he heard that Mrs. Copland had died. The last report concerning John Copland, barrister and battler, appeared in the Colonist in December 1873. It was brief and to the point: “Mr. John Copland, formerly of this city, is at Clyde, Scotland. He met with a severe accident, not long ago, by being thrown from a horse.”

There you have it, fighting John Copland, barrister, brawler and one-of-a-kind Victoria character. Did I deliver that chuckle (or two) that I promised?

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.