For Princess Victoria Haste Meant Disaster

Throughout the Pacific Northwest at the turn of the last century there was no argument as to the Speed Queen of the Seas: the CPR flagship Princess Victoria. With three funnels belching black smoke, the sleek liner raced between Victoria, Vancouver and Puget Sound ports, showing her stern to all challengers.

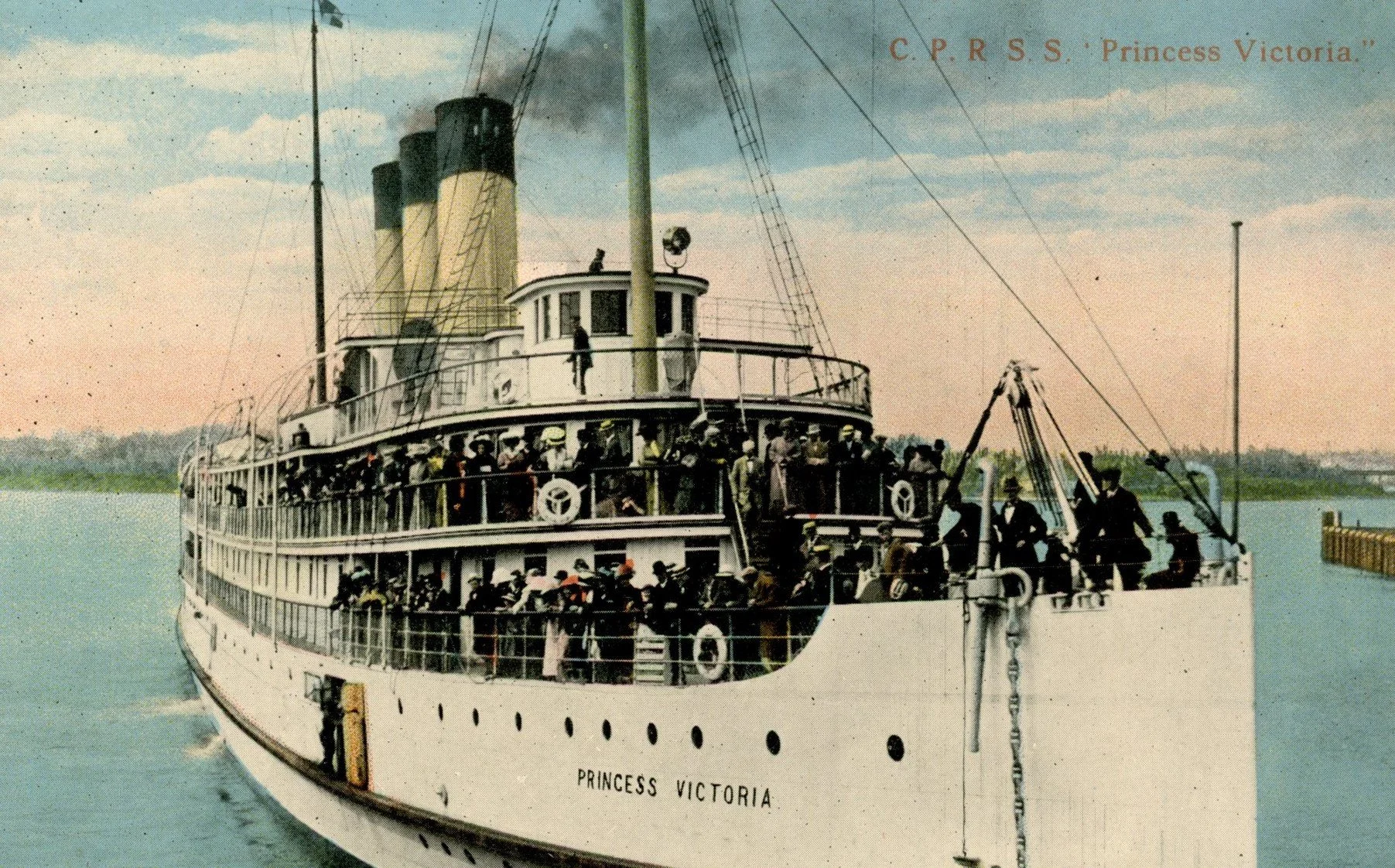

The CPR flagship Princess Victoria steams through Burrard Inlet, possibly in 1904. —Vancouver City Archives

But there was a price to be paid for such lightness of step; more than once, emphasis on speed meant carelessness and near disaster. On the afternoon of Saturday, July 21, 1906, the Princess Victoria's haste meant disaster and death for more than half of the company of the little passenger tug Chehalis.

Owned by the Union Steamship Co., she’d cleared her ways where she’d had a new propeller fitted two hours before the crash with 14 passengers and crewman. As she was chartered for a three-week cruise, she’d called in at North Vancouver to pick up two more passengers, Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Bryce.

In the meantime, the Princess Victoria had been late leaving her dock but, after clearing the old coal hulk Robert Kerr, proceeded to enter the Narrows against a strong flood tide. Due to the current’s resistance, Capt. T. O. Griffin ordered speed increased and the trim liner surged forward on her usual course, but “a little nearer the Brockton Point side of the Narrows”.

From the bridge, Capt. Griffin observed the much smaller Chehalis off the Victoria’s starboard bow and steering a course more or less parallel to that of the CPR flagship. With her greater power, the Princess Victoria soon overtook the tug, both entering the Narrows at the same time.

It’s fortunate that passengers weren’t lining the Victorias decks, as in this postcard, when she overtook the smaller, slower Chehalis. —Author’s Collection

But, opposite Brockton Point, it was reported, "it seemed to those on board the Victoria as though the Chehalis was trying to cross the bows of the CPR steamer from starboard."

Suddenly, Capt. Griffin—bearing down on the tug at 15 knots—found himself on a collision course, trapped between the closing Chehalis and a gasoline launch off his port bow. Twice, the Princess’s legendary whistle warned the Chehalis off as the liner continued to bear down upon the tug at high speed.

Instead of keeping clear, Capt. James Howse of the Chehalis appeared to hold his course. "It seemed, perhaps due to the spring tide, that the Chehalis swung more in line of the Princess Victoria, which was turned to port an effort to clear. Then the white liner struck the Chehalis..."

With horrendous impact the Victoria speared the Union Co. steamer in her port bow, pivoting the little Chehalis around to crash violently against the flagship’s side. As the protesting plates of both steamers screamed in agony, the Chehalis was forced slowly over and onto her side, the Victoria’s bow riding up and over its victim.

Instantly, those aboard the liner knew that the Chehalis had been mortally wounded.

Then, within the space of 15 horrifying seconds, Chehalis vanished, “leaving some wreckage of splintered housework, boxes, coils of rope, etc, on the surface of the water. And a number of people, not more than six or seven, were seen floating amongst the wreckage, some clinging to pieces of debris.’

In the golden age of steam, before radar and satellite navigation, collisions weren’t all that uncommon. These photos show the results of one such fender bender, this one between the S.S. Charmer, left, and the SS Tartar, centre and right, in October 1907. —Vancouver City Archives

Before the crash, upon seeing that it was impossible to avoid collision, Capt. Griffin had ordered his engines stopped and reversed. Although too late to miss the Chehalis, the order did result in the Victoria's being brought to a halt “in wonderfully quick time," and within 100 yards of the spot where the Chehalis had foundered. This, despite the fact that the flagship had had “considerable way”.

Moments later, crewmen and passengers aboard the steamer rained life belts down upon those struggling in the water, as the liner’s pilot, Capt. Robertson, took personal command of No. 8 lifeboat to begin rescue operations.

But, even before the lifeboat could be launched, a flotilla of small boats reached the scene, rescuing five survivors as No. 8 boat picked up three more. All those rescued were wearing the lifebelts thrown over the side by the Princess Victoria moments after the crash.

When Capt. Robertson and crew members reached the island of debris and struggling survivors, they found P.G. Shallcross, who asked that they leave him and pick up the women. Instead, they dragged him into the boat before searching for the others. A pearl buyer, Theodore Rich, was the next to be saved, then Robert Price of the Union Steamship Co. which owned the Chehalis who, with his wife, had boarded at North Vancouver.

Uninjured in the collision, the three were hurried aboard the Princess Victoria where stewards saw to their comfort with hot drinks and dry clothing. Also rescued were Captain Howse, Joseph O. Benwell and an unidentified man.

Of the other nine persons, including Mrs. Price, there was not a trace, it being feared that all had been carried down with the Chehalis, the other passengers having been at lunch at the moment of collision.

Missing and presumed drowned were Dr. W.A.B. Hutton, doctor of the missionary steamer Columbia; P.J. Chick, former purser of the Union steamer Cassiar; W.H. Crawford, deckhand aboard the Chehalis; 30-year-old Hilda Mason; nine-year-old Charles Benwell; two unidentified Japanese firemen and a Chinese cook.

Upon returning to her Vancouver pier, the CPR flagship disembarked the survivors. At 3:00 p.m., an hour after the tragedy, she again cleared for Victoria where officers and crew members refused to discuss the incident with reporters.

Two views of the SS Chehalis Cross in Vancouver’s Stanley Park that honours the victims of the Union Steamship Co.’s passenger tug, Chehalis. The memorial overlooks Brockton Point where the tragedy occurred in July 1906. —Wikipedia, left, and the Stanley Park website, right.

Of the Chehalis’ lost company, Dr. Hutton, physician and surgeon aboard the missionary vessel Columbia, was perhaps the best known in Victoria. Ironically, he’d booked passage aboard the northbound Chehalis so as to visit his parishioners, the Columbia being laid up during overhaul.

Two days before he went down with the Chehalis, his appointment as coroner had been announced in the Colonist.

Noted the morning daily, “He was well loved by the loggers, miners and other coast people, who had come to look upon him as their own doctor. Many a surgery case, many a broken arm or leg has he attended to at the call of some logger who has rowed for miles to find him, and many a settler has been given his services." With a young daughter, Dr. Hutton was just 34 years old.

The Chehalis, it was learned, had been chartered by Bryce and Chick who had an interest in some Queen Charlotte Sound oyster beds. Theodore Rich, among those rescued, had been aboard to examine the beds and report upon their commercial potential to an English syndicate.

In Vancouver, Capt. Howse described the loss of his steamer.

Injured in the side and with tears streaming down his cheeks, he told of the last minutes of the Chehalis: “...I was heading for the North Shore to get out of the flood current as much as possible. I thought we were making good time and did not bother about looking behind me. I had just altered my course a little more to starboard when I suddenly heard a whistle behind me, and looking back out of the pilot house, I saw the Princess Victoria right on top of me.

“There was no chance for me to get out of the way then, but I put the helm hard over and attempted to get clear. Then the crash came. It was awful.

“The Chehalis rolled clean over, something struck me on the head just as I tried to get out of the wheelhouse when she righted again. Then I saw that the Chehalis was practically cut in two and sinking...”

Upon seeing Mrs, Bryce struggling in the water, he attempted to reach her, when he was again dealt “an awful blow on the side,” telling a reporter, "It's beginning to hurt worse. I only wish Mrs. Price had been saved, and my poor engineer and firemen." Then, overcome by pain and grief, Capt. Howse fainted.

Capt. T. O. Griffin, master of the Princess Victoria, described the tragedy as “a deplorable affair”.

The Victoria was rounding Brockton Point against a “mill race” tide, he explained, when he first observed the gasoline launch on his port bow and the Chehalis on his starboard. Also on the Victoria's bridge that afternoon was her pilot, Capt. Robertson. Immediately upon sighting both vessels, Griffin said he’d ordered two whistle blasts as warning to the Chehalis that he’d pass her to port in the narrow channel between the launch and the tug.

“Suddenly I saw the tug swerve from her course and lay directly across our bows.

“I ordered full speed astern and the engines reversed at once. I could not turn to starboard [sic] without running down the gasoline launch and it was impossible to go to port for fear of striking the tug. I was in hopes that we would be able to back before the vessel struck."

The RMS Niagara showing the damage that resulted from a collision with the SS KING Egbert in 1935. —BC Archives

But when both vessels were within a boat's length of each other, he continued, "the tide seemed to swing the tug around and her port quarter struck our bow. The momentum was so great that, added to the strong tide, it rolled the vessel over and in a matter of a quarter of a minute she went down. There was no smashing of the timbers or severe shock.”

From his vantage point, high on the Victoria’s bridge, Capt. Griffin watched as a man jumped from the tug’s bow. Then came the crash, and “like a flash,” the Chehalis rolled over and disappeared.

Two days later, Griffin was arrested in Vancouver, charged with manslaughter and released on $4,000 bail. Robert Bryce, who’d lost his wife in the wreck, preferred the charge, the captain being arrested aboard ship. Upon his being remanded, it was reported, an unidentified Chehalis survivor (undoubtedly Bryce) had threatened to assault him, "there [being] considerable feeling against him in some quarters”.

Among those who believed in Capt. Griffin's innocence was W. Hester, described as a lifelong seafaring man, who’d been on board the Princess Victoria. According to Hester, the Victoria had enjoyed the right-of-way and had warned the slower tug with two blasts of her whistle which, he said, had been answered by Capt. Howse.

But the Chehalis had been powerless in the current, with the result that the CPR liner struck her amidship. "It was an unfortunate accident,” he concluded, “but no blame kind can be attached to the officers of the Princess”.

By this time the survivors of the Chehalis were able to detail their “thrilling escapes," Chief Engineer C.A. Dean (overlooked in the initial reports of the collision) having being rescued by the Brockton Point lightkeeper. Suffering from shock and exposure, Dean told how he’d been carried under with the sinking tug. Upon breaking free, “for one sickening moment,” he felt the Chehalis’s still spinning propeller blades graze his body. Then he was on the surface and swimming until spotted by lightkeeper Jones.

P.G. Shallcross, first to be rescued, told how he’d been sitting with Mrs. Bryce in the saloon when he heard someone shout that they were about to be hit by the Victoria. Leaping to his feet, he prepared to run on deck when he realized that Mrs. Bryce hadn’t realized the gravity of the situation, having remain seated.

Just as he moved towards her, Shallcross was hurled against a bulkhead.

“At the same instant the water poured in, and in the darkness I could not locate her her. Very fortunately I did not have heavy clothes on. I had changed my business suit for a flannel one, and had light shoes instead of boots. When the cabin was flooded, I thought that was the beginning of the end, for it seemed to be impossible to get out.

“Being a swimmer and used to the water, I held my breath until I felt my lungs pain, and in easing them I took a couple of gulps of water. At the same instant I felt a suction in the water; the two doors of the cabin being opposite each other, I struck on the side of one of the openings and managed to get through, though not without some difficulty. It was about a moment after that I was on the surface and breathing the good air once more.

“I went right under the Victoria and came up on the other side.

“Another moment and I could not have stood it. The water I took was choking me, and had I not got into the suction by moving around as I was in my effort to escape, I would soon have had enough water in me to send me down..."

Despite his miraculous escape, Shallcross’s problems weren’t over. Within minutes, helpless in the tide rip, he was rapidly losing strength. Upon looking up at the Princess Victoria, he recognized Miss Tatlow among the liner’s passengers who quickly threw him a life preserver.

Fellow passenger Theodore Rich owed his escape to an orange crate thrown him by a deckhand on board the Princess Victoria.

Joseph Benwell said that he’d been enjoying lunch with Mrs. Bryce, Shallcross and Chick when the Chehalis shuddered under impact. Both he and Chick reached the saloon door at the same moment, their hands clasping as they grappled with the knob. But, with their combined strength, they couldn’t force the door. Seconds later, the cabin flooded and their grip was forever broken.

Miraculously, Benwell succeeded in sticking his head through an open window. The next he knew, he was on the surface and swimming about “for what seemed a terribly long time” before being picked up. Benwell then reached into his pockets and displayed several tiny pieces of coal which, he said, must have found their way into his clothing from the Chehalis’s bunkers while underwater.

Just then, a woman approached to ask his listeners if they knew whether “Mr. Benwell's little boy was saved?”

After a pause, Benwell replied with quivering lips, "Mr. Benwell's little boy was drowned." As the woman, unaware of his identity, turned away, Benwell mournfully prepared to break the news to the lad’s family.

Robert Bryce had been in No. 8 lifeboat as it approached the Princess Victoria when he was informed that his wife was drowned. Far above, he could see Capt. Griffin and, struggling to his feet, the agonized Bryce shook his fist at the man he held to be responsible for the crash, before covering his face with his hands and collapsing in the bottom of the boat.

Built in 1897, the 54-ton wooden-hulled steam tug Chehalis had been popular with passengers as a safe and comfortable craft.

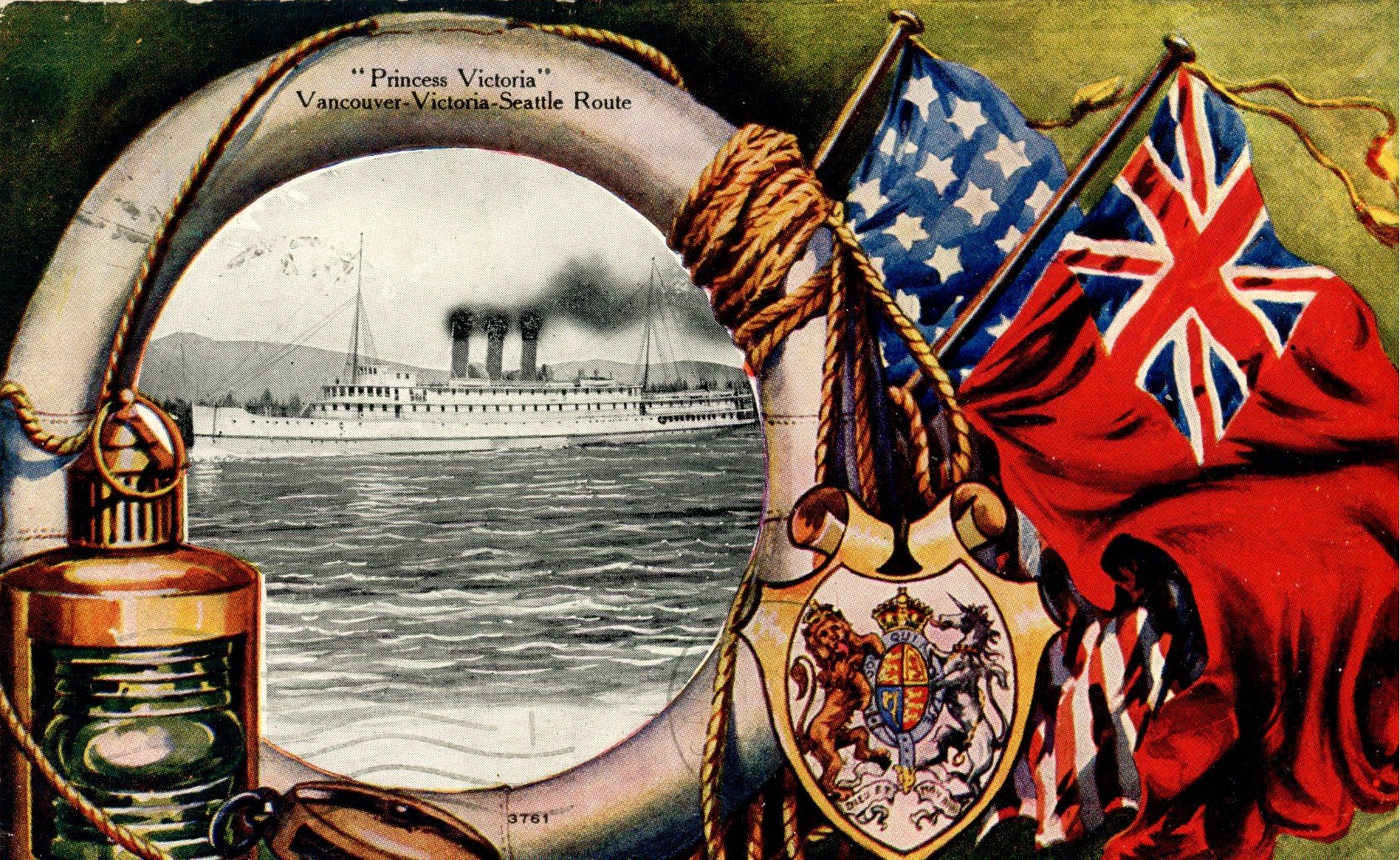

The Princess Victoria was one of the most photographed of the CPR’s coastal liners and enjoyed a long and, happily for the most part, uneventful career. The American flag shows in this artistic postcard because the famous Triangle Run included Seattle. —Author’s Collection

Her nemesis, the Princess Victoria, escaped unscathed from their fatal encounter, to write one of the more colourful chapters in Pacific Northwest maritime history. For almost half a century—and more than three million nautical miles—she attested to the foresight and courage of the man who’d had her built, Capt. J.W. Troup.

Designed to do 19 knots, “Old Vic” soon captured every speed laurel and the hearts of travellers in the Northwest. But, as with the Chehalis, she—and others—paid a heavy price for such speed.

Two years after the Brockton Point tragedy, Princess Victoria knifed into the steam schooner Ida May while southbound from Seattle. By holding her rapier-like bow into the stricken fisherman's side, the Victoria saved her from sinking. But, off Point-No-Point, while easing her way through a summer fog at five knots in August 1914, the Victoria struck the American steamer Admiral Sampson. This time the flagship’s sharp bows sliced deeply into the American vessel’s side, rupturing her fuel tanks.

As the dying steamer began to settle, her spilling oil burst into flame, incinerating at least one crew member before the Inferno was extinguished by the vessel going under.

Sixteen of the Admiral Sampson's officers, crewmen and passengers died during the five minutes it took for the steamer to vanish beneath the waves.

On this tragic occasion, at least, the Victoria's speed at the time of the collision was not in question. Years before, after her ramming of the Chehalis, authorities had prohibited ships overtaking or passing each other inside Burnaby light.