Fulfillment of Dream Came Too Late for Wealthy Dreamer

“A man out west is a man, and let him be the poorest cowboy he will assert his right of perfect equality with the best...”

Author, sportsman, dreamer. Such was William Adolph Baillie-Grohman.

Big game hunter, author and visionary W.A. Baillie-Grohman. —W.A. Baillie-Grohman

He was rich, too, and it was while hunting mountain goats in the West Kootenays in that early 1880s that he had his inspiration.

Too bad for him that, as events proved, he was no businessman.

* * * * *

The progeny of an Irish mother (a cousin of the Duke of Wellington) and an English father of Austrian heritage, hence his double-barrelled handle, the Austrian-born (1851) Grohman-Baillie divided his childhood between Ireland and Austria before articling as a lawyer. But, having spent much of his youth in the exhilarating air of the Alps, he soon wearied of the law and devoted himself to hunting big game and writing. Tyrol and the Tyrolese, his first book, published when he was 24, was followed in 1882 by Camps in the Rockies after a second hunting visit to the Kootenays, the Selkirks and several western American states.

So taken was he with this wild and undeveloped region of British Columbia that he ultimately made four expeditions. Of the second, he wrote “...As your city-worn lungs inhale the air, fresh life is infused into your whole being, and you feel it is composed not of one-fifth even but of five-fifths oxygen...”

Much like his native Alps, no doubt, where he’d participated in the first winter ascent of Austria’s highest peak in 1875. As notably, it was Baillie-Grohman who introduced the Tyrolese to skis, having been sent four pairs by his father-in-law from Norway. There’s a famous photo of wife Florence—the first of a woman skiing in the Austrian Alps.

For all his gentlemanly upbringing (private tutors before attending a leading college, his father having suffered an early mental breakdown), Baillie-Grohman seems to have been as one with the B.C. frontier. Surprisingly egalitarian for a man of such a gentlemanly upbringing, he wrote that men were men in the West where the loneliest man could stand tall and proud and “assert his equality with the best”.

He also walked the talk, equally at ease when sharing rough camp life with locals as when travelling in luxury, sahib-style.

Baillie-Grohman looks very much the English gentleman in this formal portrait. —BC Archives

In the course of these travels, which coincided with the coming of the railways and a silver mining boom, he kept an eye peeled for potential business ventures. The opportunities were there, he was sure, although not all could see them. He could only “marvel at the wonderful opportunity that millionaire, Astor of New York, had missed in passing up the development of this great land empire.”

The scheme that ultimately proved to be his undoing came to him while he was hunting in the Kootenay Flats area of southeastern B.C.'s Creston Valley.

Noting the richness of the soil, he had a brain wave. If the spring flooding could be ended by lowering the level of Kootenay Lake, these alluvial plains could be transformed into rich farmland.

A natural constriction of the lake’s outlet gave him the idea of widening it to divert the annual flood waters. He refined this further by planning a canal to divert the Upper Kootenay River into Columbia Lake at a point where the two waterways were only a mile and a-half apart.

Scenic map of Columbia and Kootenay Valley, 1913. —BC Archives

Armed with provincial government approval and a 10-year grant of 78,525 acres (318 km) fertile acres after promising to place a steamboat on the navigable part of the Lower Kootenay River, Baillie-Grohman returned to the Old Country to raise capital by writing a series of promotional magazine articles. The little British built Midge (short for midget, no doubt), was hauled 40 miles overland from Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho. This incredible feat would be one of Baillie-Grohman’s few successes.

Baillie-Grohman’s plan of Canal Flats. —BC Archives

British investors came on board but there was strong opposition to his scheme in B.C. Upper Kootenay Valley farmers, fearful of consequent flooding of their homesteads if his project proceeded, petitioned Ottawa which had jurisdiction over navigable waters. The CPR, which viewed his diversionary scheme as interfering with their transcontinental project, also complained.

Also hindering his efforts, to quote Wikipedia, Baillie-Grohman was no salesman: “Probably his impatient and untactful temperament and privileged background was not well suited to the political manoeuvring needed to mollify the Provincial Colonial Administration [sic] and counter the machinations of the CPR and other interests...”

He could build a canal but it must used exclusively for the passage of shipping, opened only to admit the passage of vessels, thus unable to control flooding. Ergo no farmlands, as he was forbidden to lower the water of Kootenay Lake below its ordinary low-water level.

Even with the offer of 30,000 free acres as compensation upon the canal's completion, Baillie-Grohman should have cut his losses. But he’d already invested unknown sums of money and four years in the project.

The reorganized Kootenay Valley Co. Ltd., with Baillie-Grohman as managing director, set out to build his canal—more than a mile long and 45 feet wide—over nine costly years.

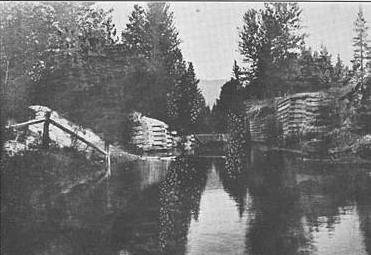

Construction at Canal Flats, 1888. —BC Archives

Upon its eventual completion, and with the construction of the CPR as far as Crowsnest Pass, only two ships ever used it, one going each way. By then Baillie-Grohman, who’d survived a murder attempt by a crazed miner who accused him of claim jumping, and a bout of mountain fever, had been ousted by his own board of directors after spending most of his shareholders’ fortunes (more, he admitted, than he’d anticipated) to no purpose and without reclaiming so much as a single arable acre.

A crew of Chinese work on Baillie-Grohman’s canal project, 1888. —BC Archives

At least he could claim to be the region’s first postmaster and justice of the peace.

A lock under construction in 1888. —BC Archives

Upon completion.

As it looked, abandoned, in 1922. —BC Archives

Ironically, in the 1930s, the need for electric power led to the construction of several dams farther downstream to control the level of the lake. As one historian noted, perhaps sardonically, “The work down by Grohman in widening the narrow outlet of the lake was of great assistance in this control.”

And, as envisioned by Baillie-Grohman so long ago, the Creston Flats area is now renowned for, among other assets, its agricultural products.

The scenic Creston Valley today. —www.tripadvisor.ca

Back in Europe by 1893, Baillie-Grohman had to sell the family manse in Ireland and a fabulous collection of antique European furniture. He returned to writing about the history of sport until, at age 70, he died of a heart attack while eating breakfast in his Austrian castle in 1921. This was after the end of the First World War when, viewed as an enemy alien by the Austrian government, he’d had to accept exile in England for the duration.

Among his many influential friends he’d included fellow sportsman and U.S. president Teddy Roosevelt.

A passage from his book, Sport and Life, captures his entrepreneurial spirit which really was an extension of his adventurousness that led him astray: “Youthful enthusiasm and a thorough belief in the future of the beautiful Kootenay country which I had accidentally stumbled upon caus[ed] me to shoulder tasks as novel as they were trying."

Novel, yes; trying, yes. Expensive, too!

A 1967 Centennial news release summed up the ironic twist to this big game hunter’s ill-fated playing at engineering in a short paragraph: “Thousands of acres of Kootenay Flats were reclaimed by dyking and draining in years that followed, but Baillie-Grohman profited not a nickel. All that remains of his dream...is a weed-grown ditch, evident from the highway between Kimberley and Inverness.”

A monument has been named for William Adolph Baillie-Grohman in Nelson and there's a plaque bearing his name on a rise that overlooks the Duck Lake Wildlife Sanctuary where visitors can gaze over a fertile agricultural plain that has been formed on the Kootenay Flats. The construction-era town that originally bore his name also survives but as Canal Flats.

His son, Vice-Admiral Harold Tom Baillie-Grohman, RN, CB, DSO, OBE commanded the battleship Ramillies at the start of the Second World War, and daughter Olga Florence became the first female Member of the Kenya Legislative Council.

* * * * *

Victoria was anything but dull, 90 years ago according to Florence Baillie-Grohman whose memoirs provide a fascinating glimpse of Victoria in the early 1890s.

As wife of William, the noted English sportsman, author and genius behind the ill-fated dike system, the former Florence Nickalls’ English stockbroker father made a fortune in American railways, and her brothers were world-class rowers. She first came to Victoria shortly after their marriage in 1887. If nothing else, her reminiscence serves as a window through which we can glimpse what was happening in the capital city so long ago; particularly as Mrs. B-G had a penchant for meeting characters.

One of the first three she recorded for immortality was a Mrs. Doane who lived next door. According to our amateur historian, Mrs. Doane was unpopular with most respectable Victorians “as she was what people would vulgarly call ‘no class,’ but she had [had] a romantic life”.

Mrs. Doane, chuckled Mrs. B-G in her diary, “knew the history of everyone. Very soon I knew the origin of most of the families—as known by Mrs. Doane! She would sometimes say of someone, with a sneer, perhaps a smart lady in society: ‘Who is she? Why, her father had only got a second-rate schooner. Of course it was easy for her to marry her man because there were so few white women here then.’

“There were many, too, whom she knew had Indian [sic] forebears.”

But there was considerably more to life in Victoria than the gossip of shrewish Mrs. Doane.

To quote: “There was plenty going on; the navy was in Victoria a greater part of the year, and there were dances, tennis parties and picnics, boating parties up the Arm of the sea [the Gorge], and many drives on a buckboard with the Drakes did I have. Added to this, there was the lovely scenery, the fine weather and the beautiful wild spring and summer flowers besides all the well-known English flowers grown in the pretty gardens."

Florence has been memorialized by having a wine named after her. —

https://www.vivino.com/US/en/baillie-grohman-florence-rose/w/8726085

There was also tragedy in the form of a smallpox epidemic which almost depopulated the city as entire families evacuated the town in hopes of escaping the scourge.

Yellow flags hung from windows, indicating that the dreaded disease had struck, decorated many homes. Most of the wealthier residents fled to Vancouver, Banff or Seattle, according to Mrs. B-G, but she, unable to afford such escape while her husband was away in England on business, had to take her chances in Victoria with her two children.

When the family doctor called and informed her that two neighbouring homes had been stricken, he suggested that she move her household to a camp for the duration. “In the first place I knew nothing about camping,” she explained in her journal, “and then I had no tents, and did not know where to camp, but that afternoon I met an old English colonel—MacCullum by name—who had a house near the Esquimalt docks, and I told him my dilemma.”

Col. MacCullum came to the rescue with the suggestion that she and her family make camp “on the far side of Esquimalt Harbour”. In fact, the good colonel not only saw to the buying of her tents but with his Chinese servant set up camp for the refugees “in a fenced-in field, with forest all around except on one side which faced the sea".

Her friends, she laughed, had been appalled at the idea of her camping out in the wilds of Esquimalt “without a man–so dangerous! To one old lady who was a tremendous gossip, I said: ‘I should hate an old man in the camp; he would be a nuisance, and if I took a young man, with my husband in England, what would you say?’ She was quite non-plussed and had to laugh and say it was quite true.”

As it turned out, the only one of the party of three adults and two children afraid to camp out at night was the Chinese servant. Mrs. B-G had to stop his desertion at gunpoint! “As he was threatening to depart, I produced an unloaded six-shooter, and told him that if he went I should shoot him—he had much better stay!

“He looked at the six-shooter for a moment and asked if I could kill wild animals. On my assuring him I could, he thought better of it, and stayed with us for the three months, and seemed perfectly happy.”

All of which suggests that the lively Florence Baillie-Grohman was no less a character than those she recorded in her memoirs.

* * * * *

W.A. Baillie-Grohamn wrote eleven books; interestingly, Camps in the Rockies, most likely to be of the most interest to non-trophy hunting B.C. readers, is available online through the University of Colorado. Seven of his titles are listed below:

Tyrol & the Tyrolese. The people & the Land in their social, sporting and mountaineering aspects (1876)

Gaddings with a Primitive People.. Being a series of Sketches of Alpine Life and Customs (1878)

Camps in the Rockies. Being a Narrative of Life on the Frontier, and Sport in the Rocky Mountains, with an Account of the Cattle Ranches of the West (1882)

Sport in the Alps in the past and present. An account of the chase of the chamois, red-deer, bouquetin, roe-deer, capercaillie, and black-cock, with personal adventures and historical notes (1896)

Fifteen Years' Sport and Life in the Hunting Grounds of Western America and British Columbia (1900)

Tyrol, The Land in the Mountains (1907)

Sport in Art. An iconography of sport. Illustrating the field sports of Europe and America from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Century (1913)