‘Ghosts of the Grade’

As I admitted in last week’s promo, I ‘borrowed’ this great title from authors and historians Ian Baird and Peter Smith. Several years ago they coined it for their ‘hiking and biking’ guide book to abandoned railways on southern Vancouver Island.

These included the two major former railway grades in the Cowichan Valley which are now the Cowichan Valley and the Trans Canada Trails, formerly the E&N Railway extension from Duncan to Lake Cowichan, and the Canadian National Railways mainline from Sooke to Lake Cowichan.

This excellent book is, inexplicably, out of print and many outdoor recreationists have consoled themselves with my own contribution to this field, Historic Hikes, Sites ‘n’ Sights of the Cowichan Valley. Alas, it’s presently sold out and undergoing remake.

Bill Irvine, left, and Doug McLeod, right, check out date on a culvert then pose at the end of the line where the discontinued E&N Crofton Spur has been ploughed under by the farmer who owns both sides of the right-of-way.

It was the Kinsol Trestle that got me started in the Cowichan Valley

My own take on hiking and cycling these railway grades had its genesis in my interest in trying to save the Kinsol Trestle (ENTER PW: BONUS) from demolition. That, happily, came to fruition and the result is, according to the latest report from the Cowichan Valley Regional District’s parks department, half a million TCT users last year!

But my introduction to the CNR goes way back, to my childhood in Saanich. I grew up one house removed from the Saanich spur; originally part of the mainline, it run all the way to Patricia Bay, but in my day it had been cut back to Cedar Hill Crossroad to, occasionally, accommodate the Sidney Roofing Co. Then it was cut back again, this time to service Borden’s Mercantile and Growers Winery on Quadra Street.

Today this stretch of the CNR (originally the Canadian Northern Pacific) is part of the phenomenally successful Galloping Goose Trail.

But for me and my friends, just hiking or biking the old grades, and I’m including logging and mining railways, isn’t enough. Sure, the great outdoors and the fresh air, exercise and scenery are great—but they’re the icing on the cake.

What we’re looking for is treasure

Sadly, you’re not likely to find this in your favourite book store or even a used copy, online—it’s out of print. Sadly, you’re not likely to find this in your favourite book store or even a used copy, online—it’s out of print.

By which I mean, we’re looking for history. And if it’s there to be found, it isn’t in the middle of what’s now a well travelled trail! It’s in the bush, off to each side of the grade.

Of the half million hikers, cyclists and equestrians who enjoyed the TCT last year, how many had so much as a clue that, a century ago, there were small logging communities scattered along much of its length to Lake Cowichan? Bennalleck, to name one, even had a school. It and the others—Camscot, Scottish Palmer, Camsell, Chanlog and others—are long gone now; not even the second- and third-growth trees were there in the ‘20s.

So, yes, these historic sites are overgrown and have left little in the way of ruins to show for their passing. But if you look closely, really closely, you can still find traces of their passing, and they still have their stories to tell. That’s what our ‘bushwhacking’ is all about—seeking them out and learning about them and the people who lived and worked there, firsthand.

In short, we’re following what Baird and Smith have called the Ghosts of the Grade.

* * * * *

Can you believe there were over 41 railways operating on Vancouver Island a century ago?

Railway historian Robert Turner tells us that, aside from the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific, there were 41 privately owned logging railways on Vancouver Island in the peak year of 1924. But, by the 1950s, trucks were taking over and, with but a few exceptions, the end was in sight for logging by rail.

To a much smaller extent, there were mining railways, too, particularly in the Nanaimo-Wellington and Nanaimo-Extension areas during the early coal mining days. I’ve already told you the story of Henry Croft’s Lenora Mount Sicker Railway.

Years ago, Jennifer and I resolved to walk the entire E&N, from Victoria to Courtenay, and the spur from Parksville to Alberni. We have about 15 and 23 miles to go to finish them. It has been quite an experience, both entertaining and educational. But walking through high traffic areas and, for miles, immediately alongside the Trans Canada Highway, isn’t to be compared with following old logging and mining grades in the peace and privacy of the woods.

A favourite has been the century-old Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing grades southwest of Ladysmith, and adjoining Copper Canyon. You actually drive over miles of former railway grades which have been converted to roads. But there are still undisturbed stretches where second-growth trees have grown up astride the old grades, in some cases all but obliterating them.

It really tasks your imagination to picture in your mind a log-laden train huffing and puffing its way through these quiet forests now, believe me!

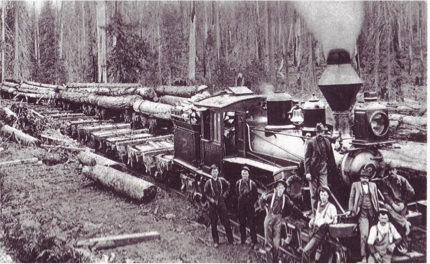

I bet you I’ve walked over the spot on the old railway grade where the No. 2 was photographed with this load of logs.

That’s where research and old photos come in. Knowing something about the area you’re searching certainly helps. After a while, experience and instinct play a role. Most camps were built on reasonably level ground and water was essential. Wherever there was a wye or the end of a spur in the tracks, you can almost count on finding some evidence of the loggers.

At the end of one spur was a large garbage dump—mostly rusted tin cans, unfortunately—where there had been a cook car on rails; in other words, a mobile kitchen. I can tell you that the cook was a heavy smoker based upon the dozens of Repeater tobacco tins we found; they, too, had rusted but you could still read the labels.

Epsom salts bottles also told us something of this cook’s culinary skills. Nothing, though, like two other dumps, at Horne Lake and in the Harewood district, which consisted almost entirely of ketchup and hot sauce bottles. And chicory bottles, a substitute for coffee. Obviously the sauces had been essential to making this camp’s meals palatable!

This is where the learning comes in

I can tell you, for example, that Benalleck consisted of two camps, one on each side of the CNR mainline. The one of the east side of the tracks was the bachelors’ quarters, on the west side were the married quarters. How do I know this? By the garbage: the bachelors’ debris is littered with liquor bottles and tobacco tins. The family camp contains women’s cream jars, broken baby bottles and other evidences of domestic life.

Because logging is a hard job, Minard’s Linament is common to both camps as are well known snake-oil medicines like Mrs. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound and NuJol, the latter a truly evil potion distilled from petroleum. (NuJol stands for New Jersey Oil Company!) NuJol even promoted itself as a cure for cancer and makes me wonder about the poor long-ago logger who, God help him, likely ordered the bottles I found by mail-order.

You can still find standing sections of trestles, the ingeniously constructed timber bridges that were just another aspect of a railway logger’s tool kit. Make no mistake, early loggers were masters of improvisation and craftsmanship. Before the chainsaw and heavy equipment, it was all done by hand with axe and saw and auger and sledge hammer that drove in the bolts that held everything together. The result were solid and serviceable structures that could be easily repaired and, even in our rain forests, have often survived decades of abandonment.

The greatest example, of course, is the Kinsol Trestle

It’s the Cowichan Valley tourism’s crown jewel. Every timber in that 600-foot-long, nine-storey-high bridge was placed by human hand. (Something to think about and to marvel at the next time you visit.)

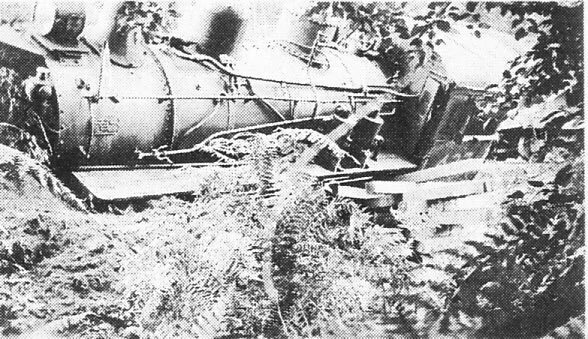

There are still evidences of train wrecks out there, too. About Mile 60 of the CNR (Trans Canada Trail) several large logs, each cut to about 20-foot lengths, line both sides of the trail. They’re left from a 1930s derailment; they were too big to salvage without a crane on rails so they’re still there. Ditto a stretch of track in the Dunsmuir area. Today, first-growth logs such as these would be worth a king’s ransom.

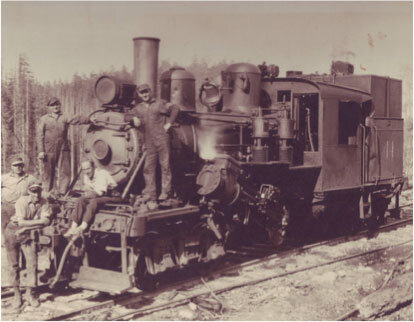

Two ‘graves’ recall the Shay locomotive that burned at Benalleck in 1928. Where it caught fire, by Stoltz Pool area you can find pieces of the locomotive, such as a sand pot and other less identifiable hunks of scrap iron. Back at the camp site, on the same side of the E&N as what I’ve termed the married quarters, is where they hauled the damaged locie to strip it of unsalvageable parts before it was shipped out for rebuilding. With the help of a metal detector and my trusty rake I’ve scratched both sides and have a ‘Tornado’ air compressor tank sitting by my back door.

This is the Shay locomotive that was burned in a forest fire at Benalleck in 1928. I’ve found parts in the ground where it caught fire and where they hauled it to strip it for rebuilding. Which explains the ‘Typhoon’ air compressor tank by my back door!

One of the worst wrecks occurred just north of Ladysmith

Oops! A wreck on the CNR (Trans Canada Trail) about Mile 60.

Mile 62 on the CNR where Gerry Wellburn, founder of the B.C. Forest Discovery Centre, operated in the 1930s.

This was a fatal head-on collision; I have two coupling pins—one from each train as they’re different sizes.

Too bad I couldn’t find anything that I could relate to the robbery of the E&N paymaster during the railway’s construction but, through research, I did pinpoint Robber’s Roost where the highwayman waited for his victim with his Winchester. (He was caught but not all of the money recovered, by the way.)

I just mentioned research again. Robert Turner’s books are an invaluable source of information as is Don MacLachlan’s history of the E&N and Dave Wilkie’s and Elwood White’s priceless history of the Lenora Mt. Sicker Railway, Shays on the Switchbacks. Not to mention old newspapers.

But academic research goes just so far

A few years ago, we actually got to ride the train from Nanaimo to Wellington on a special excursion hosted by the Island Corridor Foundation. But still no Dayliner.

There’s nothing that beats in-the-field, hands-on reconnaissance. Not to mention the added bonus of fresh air and exercise. Talk about win-win, I used to think I had the best job in the world—a job that allowed me to indulge my passion for the outdoors, photography and history then, after a session at my typewriter/computer, get paid for it! It was like having a license to steal. (Too bad about the pay, though...)

Since the mid-1960s I’ve collected bottles, yet another spin-off benefit of doing the above, and without doubt, my favourite glassware and pottery is Chinese. Almost every logging company had Chinese (and sometimes Japanese and East Indian) employees who lived apart from the white loggers. The remnants of these ghetto-style camps (usually downstream from the white camps) can make some bottle collectors, including me, drool because of the variety of artifacts one can find. No two bottles are alike—not even when they used moulds which would become worn from usage—so that even so-called machine-made Chinese bottles have characters of their own. Because the bottoms are uneven they lean at an angle, the glass is full of flaws and they had to be corked because bottle caps couldn’t fit properly. Ditto in many ways, their pottery soy sauce and Tiger beer crocks.

Best of all is the rainbow of colours that you just won’t see in old or modern domestic-made bottles: Instead of plain amber and 7-Up green, they’re pale blue and green aquas, teal blues and greens, gorgeous turquoise and yellow-brown or brown-yellow. Put them on a window sill so that the sun passes through them and you have your own stained glass window—one that speaks to you of our industrial history and of an immigrant race that was maligned and abused. But out Chinese pioneers stayed, survived and, ultimately, thrived, and it pleases me to have mementos of their historic journey to Canadian citizenship in my ‘museum.’

Fellow bushwhacker Andrew Wahlgrave sent this photo of old iron beside the Cowichan Valley Trail in the Paldi area.

Just like cars, early stoves had fancy names

Did you know that cast iron stoves, the so-called stand-alone Franklin models, were cast with fancy scroll work and model names? Names like Adanac, Sergeant, Beatty, to name just a few, and my favourite, Frolic. I’m sure we’ll all agree that having to get up at 3-4 a.m., break the ice from the water bucket and light the fire to warm the house and the wash water and to cook breakfast was a real Frolic!

I bet you don’t know that many tie plates, the flatware that sits between the rail and the wooden tie, are cast with the names of their manufacturers and their year of manufacture. Because tracks have been upgraded or repaired over the years (I’m referring to the E&N) you can see half a dozen dates in a span of just a few feet: 1938, 1952, 1980... Meaning that even a homely railway tie can speak!

The plates themselves have changed over the years as trains became bigger and heavier and so did the rails. Because the Valley’s stretch of the Trans Canada Trail, formerly the CNR, was begun as the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway, my oldest and most treasured local tie plate is CNP 1913 whereas my oldest Valley CNR tie plate is 1919.

The northern stretch of the E&N Crofton Spur ends In a farmer’s field. He obviously thinks he owns the right-of-way just because it isn’t operational.

A whistle post; note the bullet holes.

A whistlestop on the E&N mainline; Stockett is the name of a company official.

Even old lengths of rail can tell a story

I have several lengths and different gauges of rail in my collection, too. The oldest, from VL&M country, is of British manufacture and is clearly dated 1884, suggesting it started its career with the original transcontinental CPR. Loggers were the original recyclers and it clearly shows in the bits of equipment that have somehow survived the scrapyards. There’s a dump in Paldi where some of the old trucks (rolling stock) were ex-Union Pacific. Apparently company and town site owner Mayo Singh couldn’t resist a used equipment sale; alas, they’ve since been buried to get them out of sight or hauled away for salvage.

Coincidentally, my present home is—shades of my childhood in Saanich—just one house removed from the CNR Tidewater Line. My backyard came with a five-foot-length of 100-pound rail that the previous owners’ son hauled home on his wagon!

Another intriguing find, this one in Copper Canyon, was a number of English tie plates dating back to Robert Dunsmuir’s historic Wellington Colliery railway. Whereas contemporary tie plates are flat and rectangular, these are hunch-backed; instead of the rail being held in place on the plate by spikes, these ones clamp the rail to the tie. Yet another example of loggers’ re-purposing pre-owned equipment!

While on the subject of tie plates I’ll tell you that the ties themselves—all long rotted away or removed—can still, on occasion, be ‘seen.’ All you have to do is wait for a really heavy frost to thaw and you’ll clearly see the outlines of the ties before the ground settles back. Today’s surface is the height of the ballast (gravel) that filled the spaces between the ties which, of course, were sunk in the ground.

These ghostly imprints come and go with the frost

So, for several hours in the morning before everything thaws, you’ll see a line of railway ties as impressions in the gravel or soil. They’re as clear as day. Only the rails are missing!

Since I’m on the subject of ‘ghosts,’ try this one on. Several years ago Jennifer, Al and I were looking for an 1890s coal mine up-Island. Thanks to our having a key to the gate from the logging company we were able to drive almost to our destination by using what’s now the main road which originally was the railway Mainline.

We were miles from the Island Highway and the E&N Railway (then still in operation) on a warm June Sunday afternoon. After we’d made our way back to our vehicle, Al and I were standing in the roadway, discussing the results of our outing, Jennifer was scratching in the bushes.

Suddenly, distinctly—not once but twice—I heard a train whistle. A steam train whistle. Now please understand, I am familiar with the sound having grown up beside the CNR tracks in Saanich when steam was still running. And, when the wind is right, I can hear the steam locie from the B.C. Forest Discovery Centre from my house. I know what a steam locomotive sounds like.

This one wasn’t quite as shrill as the ones I’ve heard at the Forest Museum, suggesting it came from a larger locomotive.

“Did you hear that?”

Whatever, I turned to Al to ask, “Did you hear that?” But before I could speak, he asked me, “Did you hear that?”

At which Jennifer scrambled out of the bushes to ask, “Did you hear that?”

As I said, we were miles from ‘civilization’—the highway and the E&N, and no, the diesel Dayliner horn can’t be mistaken for a steam whistle.

Now ask me if I believe in ghosts.

Downtown Duncan has its own railway icon (besides the E&N trains station), this beautifully restored CNR caboose.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.