Grafton Tyler Brown: First Black Artist of the West

In February, the Royal British Columbia Museum acquired an 1883 oil painting of the entrance to Victoria Harbour by American artist, lithographer and cartographer Grafton Tyler Brown (1841-1918).

The canvas was used as part of the museum’s collaboration with the University of Victoria during February, Black History Month.

Entitled “Go West Young Man,” an accompanying lecture explored Brown’s career and his relevance as a painter today.

One art auction has listed him as “the first black painter in California. He was the only known black lithographer in America during his time, and in San Francisco he was considered the most artful. He later went on to have a successful career as a landscape painter travelling throughout California and the Pacific Northwest.”

American painter Grafton Tyler Brown staged what’s believed to have been Victoria’s first art exhibition in 1883. —Wikipedia

The newly-acquired canvas Entrance to the Harbour is said to be among the RBC’s highlights of the more than seven million objects in its possession.

* * * * *

Sixty years ago, a Victoria newspaper reporter asked, “Who was artist G.T. Brown? Where did he come from and where did he go?”

What prompted his question was the discovery of two of Brown’s paintings in an attic.

At that time—perhaps even now—only a knowledgeable few recognized G.T. Brown’s signature and the “mystery painter’s” works which have since become increasingly valuable as recent auction sales have shown.

As for who he was, where he came from and where he went, the answers to these are a matter of record although many questions concerning Brown remain unanswered.

The young G.T. Brown. — https://bcblackhistory.ca

To start at the beginning, on Feb, 22, 1841, Grafton Tyler Brown, the first of four children, was born to Thomas and Wilhelmina Brown in Dolphin County, Penn. Both parents were freed slaves from Maryland and his father was active in the abolitionist movement. At age 14 Grafton went to work for a printer and learned lithography, a form of offset printing.

This would be his first step to a successful and pioneering career as a talented landscape painter, professional lithographer and printer. In 1858, he moved to San Francisco where he first supported himself as a steward and a porter, these being the humble occupations of most persons of colour in those days.

It’s at this point that Brown’s life trajectory changed dramatically. First, came public recognition when a Sacramento newspaper praised his painting of the famous British steamship, Great Eastern.

The second, and sad to say, likely much more significant factor in the young artist’s rise to recognition, was his being “light-skinned,” as were his parents. Although he was listed in the Sacramento city directory as coloured, upon his moving to the Bay City, the Bay City directory has him down as White.

It isn’t known if Brown misrepresented himself intentionally or if people simply judged him by his appearance. The fact remains that, no longer fettered by racial discrimination, his training in lithography and what was described as his “inborn and self-taught style” became his tickets to success.

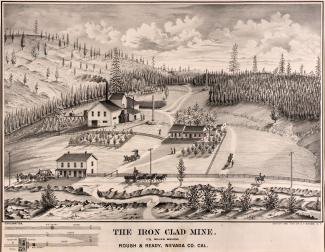

First came a job with an established lithography company owned by Charles Kuchel, 1861-67, Brown specializong in drawing panoramic views of towns and the homes of rich landowners. One of his first assignments was a tour of the Comstock Lode, the famous silver mines of Nevada, where his paintings of Virginia City were widely published and have since become historical classics.

Upon Kuchel’s death, he purchased the business from the estate and operated it under his own name as G.T. Brown & Co. Buoyed by a booming mining industry, he attracted clients seeking illustrated advertisements, maps, scrip—even labels for a B.C. salmon cannery.

According to Britannica it was during this period that, “as a way of further concealing his race,” he worked harmoniously with a newspaper publisher who was known to be racist. How ironic that this particular commission made him, unknown to the public, California’s “first African American contractor”.

For his lithography business he bought a steam-powered lithography press, built up his staff to eight and travelled extensively through California, Oregon and Nevada. This work, much like commercial art today was utilitarian but Brown brought his own distinctive touch to the scenic views, membership and mining certificates, sheet music designs and maps produced by his firm. Even his “bold, twisted” lettering style was said to be unique.

An example of Brown’s commercial work, this one of the Iron-Clad mine, a ca. 1880 lithograph on paper. —californiahistoricalsociety.blogspot.com

Among his clients were two companies still in existence, Folger Coffee and Levi Strauss.

It was In 1878, according to Wikipedia, that he published The Illustrated History of San Francisco, an ambitious project consisting of 72 topographical features of the city. One of is mining scenes was so popular that it was copied by rival printers throughout the West. By this time Brown & Co.’s clientele had extended into Nevada and included work such as “documentation of settlements, property sales, claims and city boundaries”.

But, with a downturn in mining he sold his company and moved to Victoria, about mid-summer of 1882.

Before devoting himself to landscape painting for 10 years, Brown joined a geological survey for the Dominion Government under the command of Angus Bowman. The task of reconnoitring “the country from the boundary line to Clinton on the north and east and Chilliwhack [sic] and Sumas on the west,” was an ambitious one and when Brown returned to Victoria with in November, he had a portfolio sketches.

Deciding to call Victoria home for the winter, he opened a studio in the Occidental Hotel on Wharf Street. With spring, he told the Colonist, he’d again be off to the Interior in search of further landscapes.

In the meantime, “He is purposing to do these pictures in water colour and will finish any of them to order that visitors may take a fancy to...”

Throughout his residence in the provincial capital, the morning daily never failed to praise Brown’s works in the most glowing of terms; as, for that matter, did many Victorians, it would seem. Describing him as an artist “of more than local celebrity in California and elsewhere,” the Colonist listed some of his sketches.

Brown’s works included a view of “a beautiful piece of landscape of the South Thompson looking upriver from Peterson’s hotel,” another view taken from upriver; four “equally choice” sketches depicting Shuswap Lake; two of the Okanagan’s Long lake, “one looking up from from a very popular low-lying island at high water called the Railroad, which at low water divides the lake in two, and the other from the same point of view looking both ways”.

From Okanagan Mission and “Keremev” Brown’s artistic tour proceeded to the Similkameen and lower Fraser, all the sketches “being portrayed with the exquisite tints of autumn on the foliage which gives the landscapes a rich, warm colouring that must be seen to be appreciated”.

The Brown exhibition also included some local works, such as a view of Mount Baker, from a vantage point opposite Trial Island.

Why Brown chose to make British Columbia his home temporarily becomes apparent when one notes that he that he expressed it as his opinion that “the province may challenge the world for magnificent and picturesque scenery”.

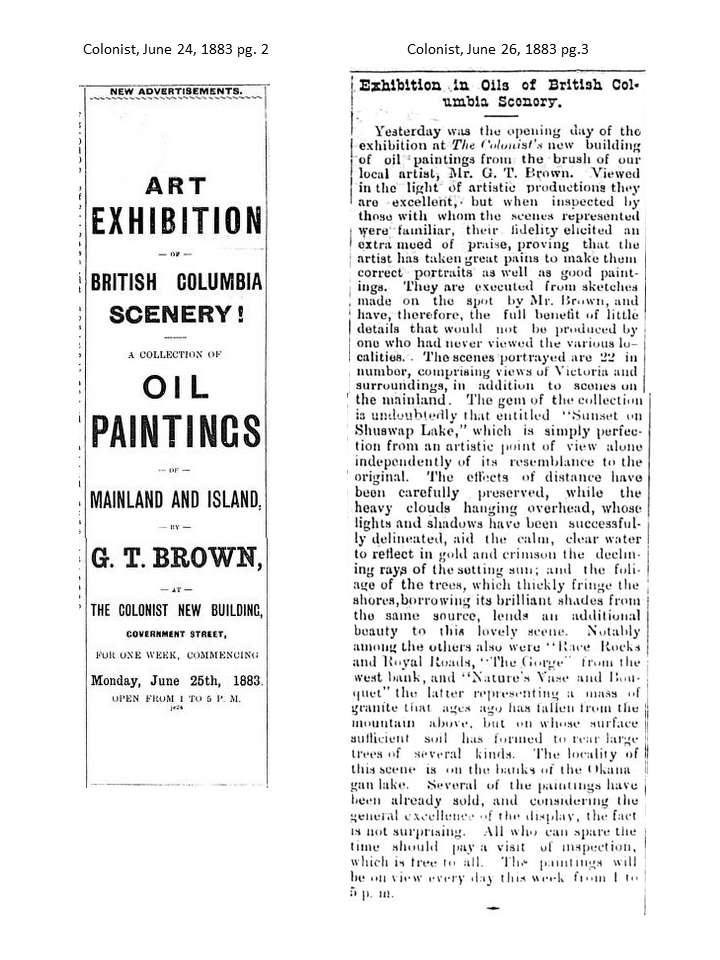

Throughout the winter, Brown laboured to transform his sketches into oils and, by the following June, the Colonist was able to announce (with almost as much pride as Brown himself) that his first exhibition was ready. For that matter, it should be pointed out that the newspaper was acting almost as a sponsor, giving Brown not only publicity but display space in its new building.

“Viewed in the light of artistic productions,” gushed a reporter (perhaps the editor himself), they [Brown’s paintings] are excellent, but when inspected by those with whom the scenes represented are familiar, their fidelity elicited an extra need of praise, proving that the artist has taken great pains to make them correct portraits, as well as good paintings.

“They are executed from sketches made on the spot by Mr. Brown. The gem of the collection is undoubtedly that entitled Sunset on Shuswap Lake, which is simply perfection from an artistic point of view alone, independently of its resemblance to the original.

“The effects of distance have been carefully preserved, while the heavy clouds hanging overhead, whose lights and shadows have been successfully delineated, aid the calm, clear water to reflect in gold and crimson the dying rays of the setting sun; and the foliage of he trees, which thickly fringe the shores, borrowing its brilliant shades from the same source, lends an additional beauty to this lovely scene...”

Representative of local works were those depicting Race Rocks, Royal Roads, the Gorge and Clover Point.

An example of his later works, this one an untitled Columbia River scene. —www.tacomaartmuseum.org

Among those who attended the exhibition was the Hon. Clement Francis Cornwall, lieutenant-governor. His Excellency must have been impressed with what he saw as he purchased a canvas entitled “Twilight on the South Thompson,” terming it “a very pretty scene”.

The exhibition appears to have been a complete success, an exuberant G.T. Brown stating that he was already selecting fresh subjects for new paintings. In fact, even before the exhibition closed, he’d managed to complete another fine landscape, this one of the Goldstream (Niagara) Falls, the Colonist recommending it as being well worth seeing.

Sketched in the afternoon, Brown’s latest work captured the pool below the falls in shadow as, from above, the sun highlighted “the foliage in rich, warm tints, giving the entire picture a clever picturesqueness”.

But even the newspaper’s enthusiasm for Brown’s artistry was surpassed by that of a reviewer who, identifying himself only as “Max,” wrote an unsolicited—and flattering—review, saying that Brown’s talent was immense, that he’d shown himself to be a master in paints, as well as having served as an example to young people.

Was this an allusion to Brown, a Black man, succeeding on his own merits in colonial white society?

Selecting four of his works, including that of Goldstream Falls, “Max” proceeded to heap praise upon praise upon the artist, concluded: “”If I were in the habit, or rather, if i had the ability of describing landscape painting, any one of these pictures would not be without a purchaser. Many of them are sold. They are works of art, exhibited by the pioneer artist of the province

“They should all be purchased of him, it were only were to encourage those (and they are few) who have a natural taste for the refined art of landscape panting.”

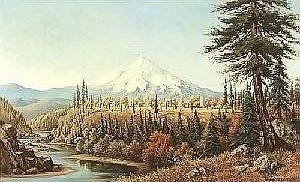

This painting of Oregon’s Mount Hood, signed, dated and painted on canvas in 1884, is mounted on Masonite and only 16.25x26.25 inches. It sold at the Butterfield, Butterfield & Dunning auction house in recent years.

Perhaps the most illuminating insight into Brown, the man, is provided by the two photographs shown above. The head-and-shoulders shot, taken apparently when he was in his late 20s or early 30s, shows him to have been handsome, mustachioed and elegantly dressed.

The full-length photo shows him when somewhat older. In this photograph Brown is bearded, formally attired and standing brush and palette in hand before his easel, a finished landscape--”On the Spallumcheen (1883)”—showing clearly.

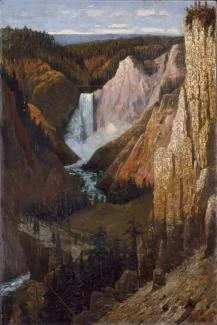

From Victoria, Brown moved to Tacoma then to Portland where he opened his own studio before following the Northern Pacific Railway to Yellowstone National Park which Britannica describes as “a great source of inspiration for him”.

Brown is noted for his eye for detail, his multitude of tiny strokes, his towering snow capped mountains and vivid colours, in particular Yellowstone’s yellow and orange rock that that “provoked a more impressionistic style, characterized by large brushstrokes..”

He finally settled in St. Paul, Minn., in 1893 where he worked as a draftsman for the Army Corps of Engineers then for the city’s engineer department. He died in 1918 after enduring a lengthy illness. Upon his passing in hospital, of pneumonia, the St. Paul Pioneer Press tersely reported:

“G.T. Brown, 77 years old, 646 Hague Avenue, for years a draughtsman in the city civil engineering department, died yesterday. He had been ill for five years. Born in Harrisbug, Penn., February 22, 1841, Mr. Brown came to St. Paul [sic] 25 years ago. He is survived by his widow. Funeral arrangements have not been made.”

In 1969, it was reported that Victoria auctioneer Wilf Lund had found two of Brown’s paintings, showing the B.C. Interior, in an attic.

Several of the artist’s local works were then in possession of the B.C. Provincial Archives which now holds the greatest number of and most significant of Brown’s Canadian works.

In the spring of 1972, the Oakland Museum, Oakland, Calif., held an exhibition entitled, “Grafton Tyler Brown: Black Artist in the West,” displaying a comprehensive collection of Brown’s original lithographs, landscape paintings and examples of the stock and mining certificates, billheads, street maps, and advertising notices produced by his firm in San Francisco.

It wasn’t mentioned whether the exhibit included a large lithograph showing San Francisco Harbor choked with shipping during the 1849 gold rush, which is considered to be a masterpiece by print collectors.

In 2017, G.T. Brown was formally recognized by the Library of Congress as “a trailblazing African American cartographer of the Pacific Northwest”.

Two years later, the Black History Awareness Society, in partnership with the Royal B.C. Museum and the Friends of the B.C. Archives, commemorated the 100th anniversary of Brown’s 1883 art exhibit in Victoria. The exhibit was highlighted by his painting, “Giant’s Castle Rock”.

At least 22 of Brown’s oil paintings of B.C. and the Pacific Northwest have been catalogued, as well as at least 40 American lithographs. How many more remain unheralded isn’t known. Those painted during his Victoria residency are clearly signed and dated, “G.T. Brown, 1883,” thus identifying their master to those who know.

Grafton Tyle Brown’s distinctive signature. —treadwaygallery.com

It’s interesting to note that his death certificate identified him as White.

As for Grafton Tyler Brown, thought to have been the first professional Black artist in California history (as well as in B.C.), each passing year brings an increasing awareness and appreciation of his gift to posterity.

An example of what Britannica described as Brown’s more impressionist period, this one, oil on canvas, a view of the lower falls, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1890. —Smithsonian American Art Museum

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.